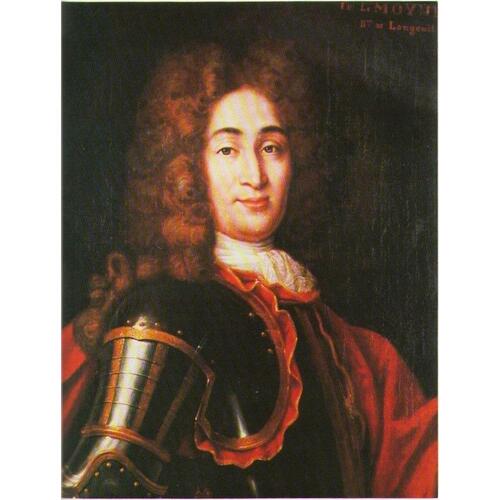

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

LE MOYNE DE LONGUEUIL, CHARLES, Baron de LONGUEUIL, the only native Canadian made a baron in New France, officer, governor of Trois-Rivières and later of Montreal, acting administrator of New France; baptized 10 Dec. 1656 at Montreal, son of Charles Le Moyne* de Longueuil et de Châteauguay and Catherine Thierry (Primot); d. 7 June 1729 at Montreal.

The eldest of the famous Le Moyne brothers was brought up in France as a page of one of Buade* de Frontenac’s relatives, the Maréchal d’Humières. He very early took up a military career, and in 1680 became a lieutenant in the Régiment de Saint-Laurent. A year later, at Paris or Versailles, he married Claude-Élisabeth Souart d’Adoucourt, a lady’s maid in the service of Madame de France (Elizabeth Charlotte, the Princess Palatine) and a niece of the Sulpician Gabriel Souart*, the first parish priest of Montreal.

In 1683 he was back in New France, since on 4 November Le Febvre* de La Barre recommended him without success to Seignelay, to replace the drunkard Jacques Bizard* in the post of town major of Montreal. At the beginning of the following year Charles Le Moyne de Longueuil, junior, received from his parents the seigneury of Longueuil and its outbuildings, and set about developing it without delay. In parallel fashion he was soon to begin to rise through the ranks of the military hierarchy in Canada and to give proof of the bravery characteristic of his family. Having become an infantry lieutenant in the regular troops in March 1687, he commanded four companies in the army which Brisay de Denonville launched against the Senecas. Longueuil acquitted himself so well that the governor, as soon as he returned to Montreal, reported him to the minister as being one of the two most remarkable officers in that campaign. In the most flattering terms he recommended that the rank of captain be granted to Longueuil, who, however, did not obtain it for four years.

At the beginning of August 1689, just after the Lachine massacre, Longueuil had his arm shattered by a musket shot while pursuing the Iroquois. The following year he distinguished himself, with his brother Le Moyne* de Sainte-Hélène, at the siege of Quebec by Phips*. The two brothers, at the head of 200 Montreal volunteers, attacked the English advance guard which was moving towards the town along the Saint-Charles River. Under the steady fire of the Canadians hidden in the thickets, the enemy had to fall back at the end of an afternoon of bitter fighting. It was there that Longueuil received a wound in the side which might have been fatal, had it not been for the protection given by his powder horn. The fracture in his arm had not yet even healed; in the spring of 1691 he had to go to the waters of Barèges, in France, to treat it.

During the Franco-Iroquois peace negotiations of 1694, the great Onondaga chief Teganissorens solemnly declared on 24 June that the Five Nations had adopted as their children Charles Le Moyne de Longueuil and Paul Le Moyne de Maricourt, replacing their father who had died. In their letter of 15 Oct. 1698, Frontenac and Bochart de Champigny earnestly requested the king to elevate the seigneury of Longueuil to a barony in consideration of Charles Le Moyne’s loyal services and the enormous expenditures he had incurred in its establishment. “His fort, his house, and all that goes with them [give] us, when we see them,” the governor and the intendant said, “an idea of the fortified castles of France.” On 26 Jan. 1700 Louis XIV therefore signed letters patent by which he made Charles Le Moyne and his descendants barons of Longueuil. This constituted striking recognition of the merits of the Le Moyne family and of the remarkable way in which the baron had developed his seigneury, “where he is endeavouring to establish three parishes,” said the king, “and to protect the said settlers in time of war he has had built at his own expense a fort flanked by four strong towers, the whole in stone and masonry with a guard-house, several large main buildings, and a very fine church, the whole embellished with all the marks of nobility . . . , and with all this there is a considerable number of servants and horses and sundry attendants, and all these buildings have cost him more than 60,000 livres, so much so that the said seigneury is at present one of the finest in the whole country, and the only one fortified and built in this way, which has greatly contributed to the protection of all the settlers on the neighbouring seigneuries. . . .”

On 3 July 1703 the cross of the order of Saint-Louis was added to the royal favours of which Le Moyne de Longueuil was to continue to show himself worthy, particularly as ambassador to the Onondagas. For since war had broken out between France and England in May 1702 over the Spanish succession, there was reason to fear an English invasion of New France from New York, in collaboration with the Indians of the Five Nations, who were neighbours of Albany. For this reason, and to preserve the fur trade in the west for the French, it was important to keep the Iroquois neutral. In the spring of 1704 Rigaud de Vaudreuil therefore instructed Longueuil to go among the Iroquois “to offset the influence of the English who are continually in their villages.” Then in June 1709, disturbed by the speeding up of war preparations at Albany and by the manœuvres of Abraham Schuyler, who had been sent among the Onondagas “to begin the war chant” and “to present the hatchet” on behalf of his Britannic majesty, the governor put the whole colony in a state of alert. In the autumn, Longueuil, who had been town major of Montreal since May 1706, offered to return among the Onondagas, who had invited him by a wampum belt to come and “set to rights the matters that the Flemish had upset.” His embassy was a success. The Oneidas, Cayugas, and Onondagas received him with enthusiasm, “each endeavouring to caress him.” They assured him they would resist both the threats and the promises of the English, and abstain from taking part in hostilities. At the time of the meeting of 17 July 1710, Longueuil managed to maintain the Onondaga and Oneida sachems in the same frame of mind.

However, the fall of Port-Royal in October 1710 shook the Indians’ confidence in French power: in the spring of 1711 Longueuil was once more sent among the Iroquois. He secured the loyalty of a number of them, but several remained susceptible to the enticements of the British. The Onondagas, however, made him a present of a piece of ground on which he built himself a lodge in their midst. He returned to Quebec during the summer, accompanied by representatives of this tribe. On 7 November the authorities of the colony wrote to the minister: “His majesty must be assured of the Sieur de Longueuil’s zeal for all that concerns his service; since the death of his brother, the Sieur de Maricourt, he has been obliged, in order to humour the Iroquois, to travel many times to see them, and even to stay for some time among them, willingly neglecting his family and all his affairs to go and humour these nations; his negotiations with them have always succeeded, with the happiest results that one can expect with nations like that; he is very sensible, Your Excellency, of the favour you obtained for him last year, and the Sieurs Vaudreuil and Raudot can assure you in advance that he will deserve all those that you give him cause to hope for.” This favour was the king’s lieutenancy at Montreal, which had been bestowed on Longueuil on 5 May 1710. The following July he received another favour: a second enlargement of his seigneury of Longueuil, the first dating from 25 Sept. 1698. In addition, on 24 March 1713, Vaudreuil and Bégon* increased “by one league of land fronting on the Richelieu River and going back to a depth of one and a half leagues . . .” the Belœil seigneury which he had bought on 25 Feb. 1711.

On 7 Nov. 1716 Ramezay and Bégon, on the basis of some information supplied by Longueuil who visited the Iroquois every year, informed the council of Marine of the need to build a post north of Niagara. The following year the baron, who on 7 May 1720 had succeeded Galiffet* as governor of Trois-Rivières, was entrusted with the task of securing Iroquois approval for the construction project of the French.

On 9 Sept. 1724 the skilful negotiator became governor of Montreal, and continued subsequently to use his influence with the Five Nations. What was particularly important at that time was to prevent the establishing at the mouth of the River Chouaguen (Oswego?) of an English fort which could ruin French trade with the pays d’en haut.

On Vaudreuil’s death in 1725, Longueuil was made responsible for the general administration of New France, until a new governor was appointed. The baron hoped to be chosen, deeming it normal to proceed, as Callière and Vaudreuil had done, from the governorship of Montreal to that of the colony. He was disappointed. It was decided not to place a Canadian at the head of New France because of the nepotism which had been displayed by Vaudreuil and his wife; the latter had been born in the colony.

In 1727, having become a widower, Longueuil, at the age of 71, married Marguerite Legardeur de Tilly, widow of Louis-Joseph Le Gouès de Grais and of Pierre de Saint-Ours. By his first wife Longueuil had had several children, among them Charles*, second baron and third seigneur of Longueuil, and Joseph, commonly called the Chevalier de Longueuil, from whom is descended the second branch of the Le Moyne de Longueuil family.

The first Baron de Longueuil died on 7 June 1729. He had been a brilliant soldier, a venturesome colonizer, and a remarkable instrument of Vaudreuil’s Indian policy.

AN, Col., C11A, 10–16, 21–47; E, 290 (dossier Charles Le Moyne, 1er baron de Longueuil). Baugy, Journal (Serrigny). Coll. de manuscrits relatifs à la N.-F., I. “Correspondance de Frontenac (1689–99),” APQ Rapport, 1927–28, 3–196. “Correspondance de Vaudreuil,” APQ Rapport, 1938–39, 12–180; 1939–40, 355–463; 1942–43, 399–443; 1946–47, 371–460; 1947–48, 135–339. Lettres de noblesse (P.-G. Roy), I, 261–73. NYCD (O’Callaghan and Fernow), V, IX. PAC Report, 1899. P.-G. Roy, Inv. concessions, II, 59–62; IV, 80. Taillemite, Inventaire analytique, série B, I.

Bonnault, “Le Canada militaire,” 276f. P.-G. Roy, Les officiers d’état-major, 170–75. [François Daniel], Histoire des grandes familles françaises du Canada (Montréal, 1867), 177–83. Émile Falardeau, . . . Les pionniers de Longueuil et leurs origines, 1666–1681 (Montréal, 1937), 35. Fauteux, Les chevaliers de Saint-Louis, 95f. A. Jodoin et J. L. Vincent, Histoire de Longueuil et de la famille de Longueuil (Montréal, 1889), 161–230. Lanctot, Histoire du Canada, II, 158; III, 37f.

Cite This Article

Céline Dupré, “LE MOYNE DE LONGUEUIL, CHARLES, Baron de LONGUEUIL (d. 1729),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 6, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/le_moyne_de_longueuil_charles_1729_2E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/le_moyne_de_longueuil_charles_1729_2E.html |

| Author of Article: | Céline Dupré |

| Title of Article: | LE MOYNE DE LONGUEUIL, CHARLES, Baron de LONGUEUIL (d. 1729) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1969 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | April 6, 2025 |