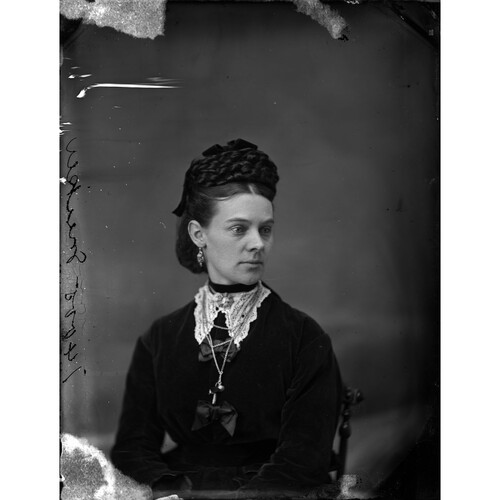

MICKLE, SARA (Sarah), local historian and heritage preservationist; b. 13 June 1853 in Guelph Township, Upper Canada, daughter of Charles Mickle, a farmer and later a lumber merchant, and Ellen Thurtell; d. 2 June 1930 in Toronto.

Sara Mickle must have inherited her great-grandfather’s literary disposition. He was William Julius Mickle (Meikle), the Scottish poet and translator of the Portuguese historical epic “Os Lusíadas” by Luís Vaz de Camões. His son, Charles Julius Mickle, immigrated to Canada in 1832, settling north of Guelph, where he established a successful sawmill. Sara was born at Langholm, the house her father had built across the Elora Road from her grandfather’s. Shortly after his death in 1879, the family settled in Toronto. The seventh of thirteen children, Sara never married. Having inherited from her father, and later her mother and sister, she dedicated herself to social causes, such as the Hillcrest Convalescent Hospital and St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, both in Toronto. Her greatest passion throughout her life was the preservation of Canada’s past.

In March 1898 Mickle was the only woman present when a committee of the Pioneer and Historical Society of the Province of Ontario met to consider ways of widening the association’s scope; she moved that the name be changed to the Ontario Historical Society, and two months later it was. She was already involved with the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Toronto, established in 1895 by Sarah Anne Curzon [Vincent*] and Mary Agnes FitzGibbon and now numbering over 200 persons. The society’s leaders were socially notable women who claimed descent from “ancestors [who] had taken a . . . prominent part in the making of Canada’s history.” Like other historical organizations of the period, it promoted, through the collection of documents and relics and the presentation of research about the past, “a unity of national purpose and a high ideal of loyalty and patriotism” that would sustain Canada’s “rising status.” Mickle contributed as both an organizer and a historian. With FitzGibbon and Lady Edgar [Ridout*] she helped stage a highly successful historical exhibition at Victoria University in 1899, she prepared three calendars on historical themes, and she wrote a number of papers on topics ranging from tombstone inscriptions to historic homes. She was a member of the WCHST executive committee almost continuously from 1897 until her death in 1930, and served the last 15 of those years as president of the society.

Known as “a gifted speaker,” she entered the political sphere as an activist for different public causes. Over the first two decades of the 20th century she was a leader in a drawn-out battle to save Toronto’s Fort York from urban and commercial encroachment on its territory. When it came under threat in 1905, WCHST rallies were held to raise awareness of the colonial fortress. The following year the society sponsored Saturday lectures at the fort for schoolchildren, an activity that reportedly attracted thousands. Efforts to educate the public were fruitful in 1907, when a by-law that would have permitted the construction of a street railway through the fort grounds was rejected by a solid majority of the city’s voters. Nevertheless, historical activists had to remain on their guard. In 1916 Mickle, as president of the WCHST, called for a monument at the fort “to interest and inform the public in the history of the place” and for a proper land survey, which might offer further protection. She was involved again in the 1920s, playing a prominent role in the Committee on the Restoration and Preservation of Old Fort York. With Sir William Dillon Otter and others, she drafted a pamphlet to “stimulate public interest in [the] value of the Old Fort as a memorial.”

But a memorial to what? Why was saving an abandoned colonial fort worth the effort? For Mickle and the WCHST the past was familiar and redolent with the social values that underpinned Canadian society. Indeed, their work was as much about preserving the social and political status quo as it was about preserving historic sites and documents. As the WCHST’s annual report asked in 1909, should “the commercial utilitarian element in our city . . . win against the patriotic sentiment and loyal belief in the value of the lessons of our past history”? According to the organization, earlier struggles to maintain ties with the British empire must not be forgotten, particularly in 1910-11 when the Naval Service Bill and reciprocity were being debated in parliament and the daily press. The society supported the war effort, its members assisting in the activities of the Canadian Red Cross and Mickle, in one of her yearly presidential addresses, calling for empire-wide unity. For the same reason, Mickle and the WCHST had joined the OHS and other organizations in a fight against a proposal to erect in Quebec City a memorial to the American major-general Richard Montgomery*, who died while leading an attack on that city in 1775. Petitions were sent over a period of ten years (1898-1908) to the mayor of Quebec, the minister of militia and defence, the governor general, and the king. The notion of placing a monument to a republican invader was repellent to Mickle’s group, which described itself in the text of one petition as “a band of women . . . united only by the common bond of patriotism for the study of our country’s history, and the preservation of its memorials and for the promotion of loyalty amongst its peoples, especially the children, with the aim of perpetuating the history of those who endured, fought, suffered and died to maintain the supremacy of the British Crown.”

Mickle’s last major work was the restoration of Colborne Lodge, the 1837 home of artist-architect John George Howard*. He had turned over to the City of Toronto much of the land that became High Park. The lodge in the park’s grounds had been a fine and unique structure but by the mid 1920s, when Mickle took the leadership in restoring the house, it had fallen into a “desolate state.” She told the mayor that, like other cities, Toronto should have such a place to give citizens “a picture of domestic life long ago.” She was tireless in her curatorial efforts, and “never rested until she had had a little talk” with anyone who had ever worked in the house. Her work on the lodge earned her the rare praise of George MacKinnon Wrong*, dean of Canadian historians, who recognized the restoration as “an interesting achievement.” His approbation was a significant departure in an era when women’s historical efforts were often criticized as amateurish and second-rate.

While Mickle made local history her focus of interest, her goal throughout was to provide Canadians with reminders of their place in something larger: the British empire. Believing that “the need for true patriotism is great,” she chose research subjects that demonstrated loyalist values. For her, history was not simply a vocation; it was a public-spirited pursuit and an expression of the desire of her generation of native-born, upper-middle-class women to play a role in the formation of Canadian identity.

Sara Mickle is the author of “Colborne Lodge” and “The owner of Colborne Lodge” in Women’s Canadian Hist. Soc. of Toronto, Trans., no.26 (1927-28): 57-59 and 60-61.

AO, F 1090; F 1139-2, 30 March 1898; F 1180-11, ser.K, file 19; RG 22-305 nos.4569, 23764, 64864; RG 22-318, no.1764. Private arch., David Kimmel (Montreal), [Alan Cane], “Family history and letters: Cane/Armitage/Mickle/Rowe.” Canadian annual rev., 1929/30. Colborne Lodge, High Park, Toronto, Canada, first occupied December 23rd, 1837 ([Toronto, 1951]). S. M. Cook, “Seventy years of history, 1895-1965,” Women’s Canadian Hist. Soc. of Toronto, Trans., no.29 (1970). Creating historical memory: English-Canadian women and the work of history, ed. Beverly Boutilier and Alison Prentice (Vancouver, 1997). “A gifted lady,” Saturday Night, 21 June 1930: 7. Gerald Killan, Preserving Ontario’s heritage: a history of the Ontario Historical Society (Ottawa, 1976). Janet Miron, “The Women’s Historical Society of Toronto: preserving the ‘food of loyalty and the drink of patriotism’” (unpublished paper prepared for York Univ., North York [Toronto], 1996). Cecilia Morgan, “History, nation, and empire: gender and southern Ontario historical societies, 1890-1920s,” CHR, 82 (2001): 491-528. “The Woman’s Canadian Historical Society of Toronto: report of regular monthly meeting, held May 30, ‘98,” Canadian Home Journal (Toronto), 4 (1898-99), no.3: 12. Women of Canada (Montreal, 1930). Women’s Canadian Hist. Soc. of Toronto, Annual report, 1896-1930. Donald Wright, “Gender and the professionalization of history in English Canada before 1960,” CHR, 81 (2000): 29-66.

Cite This Article

DAVID KIMMEL and JANET MIRON, “MICKLE, SARA (Sarah),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mickle_sara_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mickle_sara_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | DAVID KIMMEL and JANET MIRON |

| Title of Article: | MICKLE, SARA (Sarah) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | April 2, 2025 |