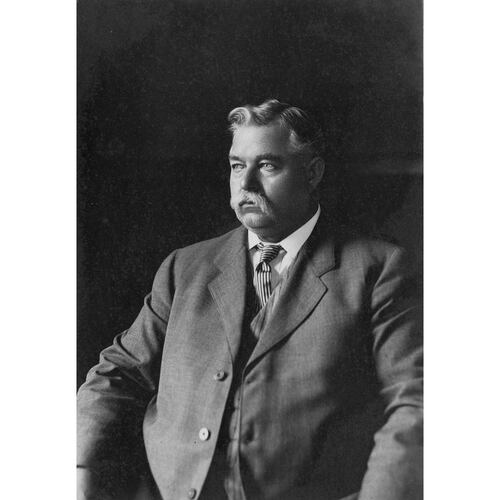

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

FLEMING, ROBERT JOHN, businessman, temperance crusader, politician, and civil servant; b. 23 Nov. 1854 in Toronto, son of William Fleming and Jane Cauldwell; m. first 23 Dec. 1879 Margaret Jane Breadon (d. 5 April 1883) in Montreal, and they had a daughter; m. secondly 23 Oct. 1888 Lydia Jane Orford (d. 20 Sept. 1937) in Toronto, and they had four daughters and four sons; d. near there 26 Oct. 1925.

Robert J. Fleming, deemed one of Canada’s “greatest executives” at his death, started out in a Horatio Alger style. Born of poor Irish parents on St David Street in Toronto’s Cabbagetown district, he dropped out of Park Street School to take a position as a stoker in an office. After attending business school at night, the ambitious youth entered the feed, coal, and wood business in the mid 1870s. By 1885 he had moved into real estate and finance.

Christian principles and social reform were at the centre of Fleming’s life. A devout Methodist affiliated with the Liberals, who were more likely to be ardent prohibitionists than most other groups, he became involved with temperance in his twenties. Following his election in 1886 as an alderman for the wet ward of St David’s, he pushed for the reduction of liquor licences in Toronto, a position many believed would cost him votes, especially among the Irish, but he was so engaging that he was easily re-elected in 1887, 1888, and 1889. Mayor William Holmes Howland*’s most articulate temperance crusader, in 1887 he succeeded in having a by-law passed to reduce licences. In 1892, with Liberal support, he ran successfully for the mayoralty on a reform platform that included opposition to the operation of the Toronto Railway Company on Sundays. His unpretentious manner and dress, scrappy and entertaining platform style, unwavering support of the working class, and Christian reformist ideals earned him an affectionate nickname – the People’s Bob. Riding on his enormous popularity, he was returned in 1893, 1896, and 1897. During the 1897 campaign his shift, to support Sunday cars, brought accusations of bribery. By this time he had moved to the front ranks of the temperance cause, primarily as treasurer of the Ontario branch of the Dominion Alliance for the Total Suppression of the Liquor Traffic and vice-president of the national body. He had served as president of the national prohibition conference in Montreal in 1894 and his Sunday temperance meetings in the Horticultural (Allan) Gardens in Toronto were widely attended. Along with James Laughlin Hughes* and William Houston*, he formed a small band to support female suffrage, largely in hopes of sustaining women’s support for temperance.

Hard hit by the real estate collapse of the 1890s, Fleming resigned from the mayoralty on 5 Aug. 1897 to become assessment commissioner for the city. In review, the Globe claimed he had accomplished more “good reform in a few years than all the mayors had over the previous ten years.” He had fought for a minimum wage for public workers and, in his best known contribution to city management, presided over the creation of a board of control in 1896 [see Samuel Morley Wickett*]. After taking on the added job of property commissioner in 1903, he drew on his experience in realty to facilitate the city’s acquisition of large pieces of land.

Although Fleming enjoyed public service, he left his job in December 1904 for a much higher salary as general manager of William Mackenzie’s Toronto Railway Company. He would hold this position, which allowed him to pay his creditors, until the company became part of the Toronto Transportation Commission system in 1921. His talent for inspiring confidence did much to shield the TRC’s directors, and the associated Toronto Power Company, from the attacks of reformers on the railway’s corrupt control of city transit. When, however, he pushed in 1906 for the acquisition of property at old Fort York for a new streetcar line, the project generated concern within the militia department and Toronto’s heritage groups [see Sara Mickle]. One major opponent of the TRC, city controller Francis Stephens Spence*, claimed in 1908 that “there is a general bitterness, a hostility, the spirit of Flemingphobia,” but the public remained unwilling to attack the agreeable Fleming directly. (At the same time his involvement with Spence in the temperance movement provides an excellent example of the ability of R. J., as he was also known, to work with his critics.) Fleming would eventually manage or serve on the boards of several other Mackenzie firms, including Toronto and Niagara Power, Electrical Development, and the Winnipeg Electric Railway. It was this association that brought him into confrontation by 1917 with Sir Adam Beck in his campaign for public hydro and new radial railways in Ontario. Adding to the security provided by a place in the Mackenzie group, Fleming, a one-time director of the Gold and Silver Mines Development Company and president of the Rossland Gold Mining, Development and Investment Company, had profitably re-entered the real estate, stock, and mining markets. Public trust led to his appointment to the board of the Toronto Harbour Commissioners in 1921. Drawn by the ongoing issue of radials on Toronto’s waterfront, he ran for the mayoralty a final time in 1923, only to lose to Charles Alfred Maguire by 840 votes.

Fleming seems to have led a simple lifestyle. When his Cabbagetown neighbours complained about the cattle at his home on Parliament Street - a vestige of his youth, when his parents had kept livestock - he moved about 1902 to a small estate on St Clair near Bathurst, though his Jerseys would continue to draw criticism. He also owned a farm in the Whitby area. In Toronto, he attended both St Clair Avenue Methodist (St Matthew’s United) Church and the more elitist Timothy Eaton Memorial; still committed to temperance, in 1923 he became president of the Dominion Alliance. He moved again, in 1924, to the 955-acre Donlands Farm, between Leaside and the Don River, which he had bought two years before from William Findlay Maclean. He died there suddenly of pleurisy in October 1925, leaving an estate worth more than $1 million, and was buried in the city in Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

Robert J. Fleming’s career as a public servant had spanned less than two decades, yet thousands of Torontonians and prominent figures from other parts of Canada turned out to mourn his passing. The Globe’s lengthy coverage claimed he had been “one of the best-known and most personally popular figures in the city.” Mayor Thomas Foster ordered its flag flown at half mast. The source of Fleming’s appeal was his knack for combining practical politics, reformist zeal, and an exuberant personality. His unquestionably ethical behaviour and kindly Christian aura won him the respect of many adversaries. Ontario premier George Howard Ferguson*, a staunch opponent of his prohibitionist campaigns, noted sadly that, with Fleming’s demise, “a great public figure has been removed.”

ANQ-M, CE601-S109, 23 déc. 1879. AO, RG 22-305, no.53233; RG 80-5-0-165, no.14446; RG 80-8-0-1015, no.37912. Globe, 27–28 Oct. 1925. Toronto Daily Star, 28–29 Dec. 1906; 17 Feb., 30 Aug., 14 Oct., 25 Nov. 1922; 23 May 1924; 26–27 Oct. 1925. Christopher Armstrong and H. V. Nelles, The revenge of the Methodist bicycle company: Sunday streetcars and municipal reform in Toronto, 1887–1897 (Toronto, 1977). Canadian annual rev., 1901–24/25. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Graeme Decarie, “Something old, something new . . . : aspects of prohibitionism in Ontario in the 1890s,” in Oliver Mowat’s Ontario, ed. Donald Swainson (Toronto, 1972), 154–71. Directory, Toronto, 1875–1925. C. A. S. Hall, “Electrical utilities in Ontario under private ownership, 1890–1914” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1968). Middleton, Municipality of Toronto. H. V. Nelles, The politics of development: forests, mines & hydro-electric power in Ontario, 1849–1941 (Toronto, 1974). W. R. Plewman, Adam Beck and the Ontario Hydro (Toronto, 1947). V. L. Russell, Mayors of Toronto (Erin, Ont., 1982). Charles Sauriol, Remembering the Don: a rare record of earlier times within the Don River valley (Scarborough, Ont., 1981), 107–12. F. S. Spence, “Some suggestions as to Toronto Street Railway problems,” in Saving the Canadian city: the first phase, 1880–1920 . . . , ed. Paul Rutherford (Toronto, 1974), 59–63. Who’s who in Canada, 1922.

Cite This Article

GAYLE M. COMEAU, “FLEMING, ROBERT JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fleming_robert_john_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fleming_robert_john_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | GAYLE M. COMEAU |

| Title of Article: | FLEMING, ROBERT JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2025 |