Source: Link

HARRIS, ROBERT, artist and teacher; b. 17 Sept. 1849 in Tyn-y-groes, Wales, second of the seven children of William Critchlow Harris and Sarah Stretch; m. 22 May 1885 Elizabeth (Bessie) Putnam in Montreal; they had no children; d. there 27 Feb. 1919 and was buried in St Peter’s Cemetery, Charlottetown.

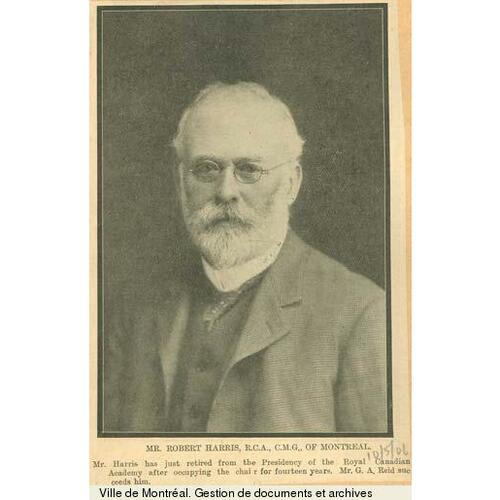

During the last two decades of the 19th century and the first two of the 20th, Robert Harris was the most renowned portrait painter in Canada; sitters came from as far away as New York City to pose for him. The more than 300 portraits known to exist in private and public collections represent a microcosm of Canada’s business and social élite.

In the company of his parents and siblings Harris celebrated his seventh birthday on board the Isabel bound for Charlottetown. His father had visited Upper Canada in 1854. Raised with the expectation of becoming a gentleman farmer but without the means, unqualified for any trade or profession, impractical dreamer that he was, he had seen for himself the advantages of emigration. Instead of taking his family to Upper Canada, he was persuaded to go to Prince Edward Island, to try his hand at farming or business. Shortly after his arrival in 1856, he entered a partnership to process and can lobster and pork. His wife, Sarah, took charge of the family as they moved from house to house, making sure the children received a good education. The boys were sent to Prince of Wales College in Charlottetown. From early childhood Robert was almost totally preoccupied with drawing, copying the illustrations from English magazines as soon as they arrived. Sarah encouraged her son and had painting materials sent from Liverpool.

Harris learned to play the flute and sang in the church choir. Like his brother William Critchlow, he played the violin. Charlottetown was a musical community, but there was no comparable interest in or support for art. Knowing that if he got to Liverpool, his mother’s family would take care of him, Harris decided to leave Prince Edward Island in order to further his studies in art. As much as he enjoyed sketching the landscape of the Island, he needed intellectual contact with those who would understand his interest in people and his wish to paint them. This project would require money and he was barely 15 when he went to work for Henry Jones Cundall, a Charlottetown surveyor and land agent. By 1867 he had saved enough.

Once in Liverpool, Harris obtained a student pass for the public library and museum, which contained a large natural history display and a good collection of casts from the antique and the best modern statues. Twice weekly he copied from the casts, a practice he would repeat later at the South Kensington Museum, London, and in Boston. He attached great value to drawing from casts, since it required accuracy and taught a student the structure of the human body. In 1883, when teaching at the school of the Art Association of Montreal, he would make copying from casts obligatory. Like the French artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, he believed that drawing is the true art, and essential in portraiture. Harris spent about three months in England, mostly in Liverpool. On his return to Charlottetown he again found employment with Cundall and he did accounting for a lawyer. He was more than ever determined to become a portrait painter.

In the fall of 1872, before leaving for Boston, where he would spend almost two years, Harris was commissioned, through contacts made by his mother, to paint portraits of the speakers of the Island’s House of Assembly at $30 a canvas. The portraits were to be executed from photographs so that he would be able to carry on with the series while in Boston. Another project he would complete in Boston was a painting of William Garvie*, commissioner of public works and mines in Nova Scotia. David Honeyman*, curator of the Provincial Museum in Halifax, had agreed to purchase the work, “if it is a good portrait.”

Harris arrived in Boston in January 1873. He spent many evenings engraving views of the city and of objects in the Museum of Fine Arts, to be forwarded for reproduction in Halifax newspapers. Two publishers, James R. Osgood and Company and Shepherd and Gill, approached him to illustrate books, and he eventually did some work for Shepherd and Gill. What he enjoyed most was drawing from life at the Lowell Institute. Four mornings a week he attended Dr William Rimmer’s classes in art anatomy. In the afternoons and evenings he drew, either in his lodgings or at the Boston Athenaeum.

Such intense, continuous work led to a general weakening of his eyesight. He wrote to his mother, “I can work all day without feeling any inconvenience at all, but I cannot do anything at night.” A specialist consulted in April 1874 ordered him to return to Prince Edward Island and rest his eyes for a minimum of six months. By the fall he was back in Boston, and he would stay there until April 1875. His two years of work, study, and attendance at concerts and lectures had provided him with self-confidence and had nurtured even greater ambitions. He had already developed a recognizable style that was praised in the Boston Transcript. His use of colour was influenced by the Barbizon School and the mastery with which he painted subjects’ eyes was already evident. Throughout his life, however, he never believed that he was as good a draftsman as others claimed. Between 1871 and 1875 he completed 61 portraits, including those painted while in Boston. Among these are representations of several speakers of the assembly, Thomas Heath Haviland*, a mayor of Charlottetown, William Alfred Weeks, a prosperous Charlottetown merchant, and judge Edward Palmer*, as well as Nova Scotians Joseph Howe* and Bishop Hibbert Binney*.

It was not until October 1876 that Harris saved enough money to continue his studies in England. He intended to copy paintings at the National Gallery, but was frustrated to discover that although only students were admitted on Thursdays and Fridays, they were there in the hundreds, with several easels around the best pictures. He managed, however, to paint a copy of a Velázquez and began studies of two heads by Sir Joshua Reynolds. In late December or early January he enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art and later he attended the Heatherly School of Fine Art. He was elected a “temporary visitor” at the Royal Colonial Institute, where he attended lectures and participated in debates. Afterwards, he returned to Liverpool. All this time he had supported himself with illustrations and paintings executed from photographs sent from Canada. In Liverpool and Ormskirk he completed six portraits of local people, including those of a wealthy patron, Luke B. Brighouse, and his two sons. Brighouse would later ask him to paint some biblical and historical scenes.

Harris arrived in Paris in October 1877. He joined the group of young painters working at the Atelier Bonnat. Léon Bonnat, one of the best painters of historical scenes in France, was not a paid professor but a voluntary adviser who dropped in now and again to criticize the work of the group. More or less on his own as far as instruction was concerned, Harris learned to enrich his use of colour and developed an impressionistic technique. Although he participated in the partying and fun at the atelier, he developed disciplined work habits which would stay with him throughout his career. The Paris sunshine bothered his eyes. In Charlottetown and Boston he had found people who could read to him. In Paris he felt “the want of reading tremendously, I save my eyes entirely to work as much as I can in the day, take a walk after dinner and generally go to bed early.” He gained an appreciation of French life and customs, and made several visits to the universal exposition in Paris. His travels and creative activities gave him experience beyond the grasp of many young Canadian painters. In later years he would stress the value to Canadians of study overseas.

Harris returned to Charlottetown in January 1879. As much as he might have wished to remain on Prince Edward Island it was, he felt, no place for a portrait painter depending on commissions and sales. Still, according to the entries in his “sitter book” he completed 18 portraits between his return to Charlottetown and his departure for Toronto in the fall of 1879. Included in this group is a fine portrait of his mentor and friend, Cundall. Before leaving Paris he had shipped a number of paintings to Toronto for exhibition with the Ontario Society of Artists. He knew that his training abroad would almost certainly guarantee that some of them would be accepted and well received. For guidance he wrote to Lucius Richard O’Brien*, the society’s vice-president, asking about the possibility of setting himself up in Toronto as a portrait painter. O’Brien replied on 14 Aug. 1879 that Toronto had no lack of portraitists and other artists. “Still, judging from what I have seen, your work would be among the best, if not better than anything we have and you would have a fair chance with the others. Success in portrait painting seems to be very much a matter of push and business attack and of your capacity in this way, I cannot judge.” Business acumen had long since been acquired by Harris, a result of his early difficulties in collecting fees from some of his Island clients.

Warmly welcomed in Toronto, Harris found that he already had a sound reputation. He established a friendship with O’Brien that would have far-reaching effects. O’Brien had held discussions with the governor general, Lord Lorne [Campbell], concerning the establishment of a national academy of art. In January 1880 Harris received a formal letter from O’Brien informing him that the governor general had nominated him a founding member of the Canadian (later Royal Canadian) Academy of Arts. About that time he was invited to paint the children of a family in Peterborough. Two other groups of children, the Stetham family (1880) and the Burnside family (1881), would follow, both of them revealing his empathy with young people. Similar empathy, a necessity in good portraiture, can be seen in his studies of street urchins and in The news boy (1879). Harris’s first institutional commission in Toronto, the portrait of the Reverend George Whitaker*, provost of Trinity College, was completed in the autumn of 1880.

As a result of Harris’s extensive experience in illustration, John Gordon Brown, editor of the Toronto Globe, commissioned him to go to Lucan, Ont., where on 4 Feb. 1880 James Donnelly* and members of his family had been murdered. Brown wanted Harris to make drawings of the seven men accused of the homicides. Thus Harris travelled first to London, where the prisoners awaited trial. They used every subterfuge to hide their faces, but Harris, a skilled observer who was quick with his pencil, made some accurate likenesses. He then went on to Lucan to sketch the scene of the crime. Brown was delighted with the results and would later commission other illustrations, including portraits of the members of the syndicate to construct the Canadian Pacific Railway.

In late February Harris went to Ottawa as one of five men appointed to a committee of management for the academy. His painting The chorister, completed on 8 February, was accepted as his diploma painting, and as such would become part of the initial collection of the National Gallery of Canada, opened two years later [see John William Hurrell Watts]. Harris stayed in Ottawa for the inauguration of the academy exhibition on 6 March 1880. Further recognition of his status was his appointment as a representative of the Ontario Society of Artists on the committee of the Provincial Exhibition in February 1880.

Harris enjoyed Toronto. A high Anglican, he attended numerous services at different churches, since one of his pleasures was listening to good sermons. Another pleasure was taking out his sketchbook and drawing pretty young ladies in the congregation. He had worked almost continually since his arrival in the city. Even a visit to Prince Edward Island during the summer of 1880 was spent preparing an illustration for Picturesque Canada (2v., Toronto, 1882-[84]) [see O’Brien*]. He complained of the strain of having to work with those sitters who patronized the arts: “The people who want portraits are those who know nothing of art.” The classes he had taught at the Ontario School of Art since January 1880, his duties connected with the academy, and the vice-presidency of the Ontario Society of Artists, to which he had been elected in May 1880, added to his busy schedule. In addition, John Wilson Bengough* and his brother, publishers of Grip, twice pressed him to accept the art editorship of an illustrated magazine they were about to publish, an offer he turned down. It was time to refresh himself by returning to Europe. After finishing the portraits he had in hand, he disposed of several unsold paintings through public auction, returned to Prince Edward Island, and sailed for Liverpool in October 1881.

His acceptance in Toronto and the promise of additional commissions meant that now he had a modicum of financial security. Dapper and well dressed, on his second visit to Paris he was no longer a penurious student. He submitted a painting to the Paris Salon. It was accepted. A second painting, a better one in his opinion, was rejected by the Royal Academy of Arts in England, to his disgust. Surprisingly, it was in Paris, apparently, that Harris first heard talk of what would be his most important commission, a painting commemorating the Fathers of Confederation. “The government painting,” he would call it. Since he already faced open professional jealousy because of his financial success, he knew he would need help in acquiring the commission. He wrote from Paris to Jedediah Slason Carvell*, a senator from Prince Edward Island, requesting him to “get the order fixed.” After painting landscapes outside Paris, he went on to Rome and Florence in September 1882. Back in London by February 1883, he rented a studio and set about preparing works for the forthcoming exhibition of the Royal Canadian Academy. This time he was gratified to have a painting accepted by the English academy. Unable to wait any longer for a decision concerning the proposed commission, in March 1883 he went to Ottawa. After meetings with Carvell, he travelled to Montreal to begin portraits of businessman Hugh McLennan* and his wife. He found that “the French element makes [Montreal] more interesting than Toronto.” The McLennans encouraged him to settle there permanently, assuring him that he would get enough sitters.

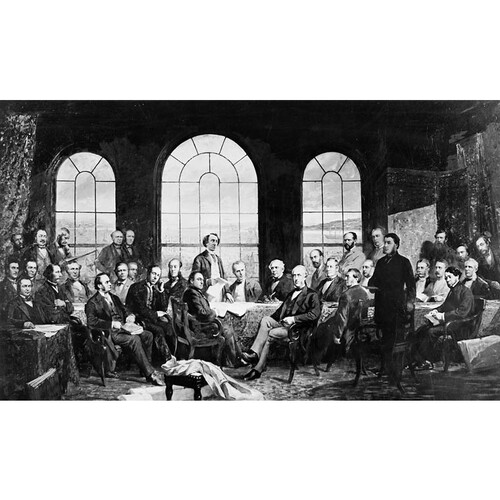

In May 1883 the Charlottetown Daily Examiner reported that the proposed contract for a painting commemorating the confederation of the British North American provinces was to be awarded to Harris. Negotiations were completed for a painting of the Charlottetown conference, although later the setting was changed to Quebec. Because the larger conference at Quebec involved additional portraits, friends advised him to ask for more than the agreed-on $4,000. Overjoyed with the commission and expecting the income earned from reproductions of the painting to be considerable, Harris settled for the original sum. The copyright was never, in fact, assigned to him. What might have been a source of satisfaction eventually became one of considerable bitterness.

Harris arranged to complete the preliminary work in Charlottetown. He sent a letter and questionnaire to each delegate or his family. From the 33 questionnaires he obtained 20 replies. Other helpful sources were the photographs taken by William Notman* or his firm, and those by William James Topley, who had opened a branch of the Notman firm in Ottawa in 1868. Harris now had enough information about complexions and colours of eyes and clothes to begin the rough outlines. Making a small preliminary oil painting, he blocked in colour tones and volumes for the proposed final work, which was to be 61 by 141 inches. He visited Quebec and made drawings on the site of the Parliament Building. In the large preliminary drawing, or cartoon, and in the final canvas, he included views of the St Lawrence River as seen from the Citadel.

Harris ordered a specially prepared canvas of the finest quality to be delivered to his Montreal studio. It arrived on 7 October, when he was beginning a busy schedule of lectures and classes at the Art Association of Montreal. Portraits and genre paintings made further inroads on time that should have been concentrated on the important government commission. An additional distraction was his election to the Athenaeum Club. The only artist who was a member, he regarded the Athenaeum as a splendid source of sitters. The McLennans had found him lodgings at the boarding-house of a widowed friend. Elizabeth Putnam, the widow’s daughter, was an attractive 23-year-old and Harris promptly fell in love with her. The winter of 1883–84 was the busiest time in his life. On 7 April 1884 he wrote to Sir Hector-Louis Langevin*, minister of public works, asking permission to show the painting of the Quebec conference in the forthcoming exhibition of the Canadian academy in Montreal. Press and public were enthusiastic about Meeting of the delegates of British North America [to settle terms of confederation, Quebec, October 1864], completed a few months short of 20 years after the event. It was hung in the railway committee room in the centre block of the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa and was only seen outside Ottawa again in 1910, when it was included in an exhibition of Canadian art in Liverpool, England. It was destroyed in the fire that gutted the centre block in 1916.

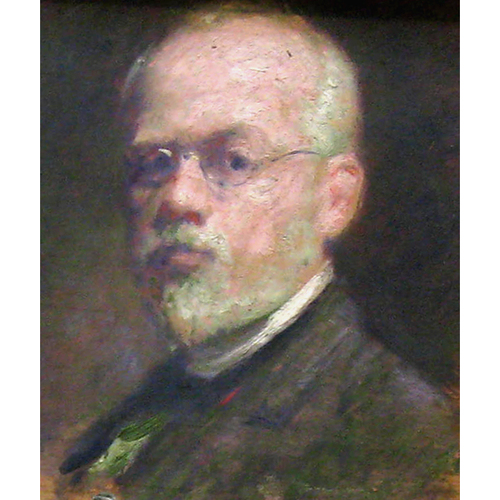

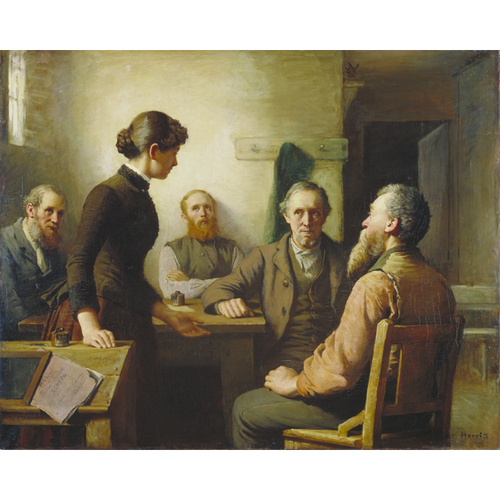

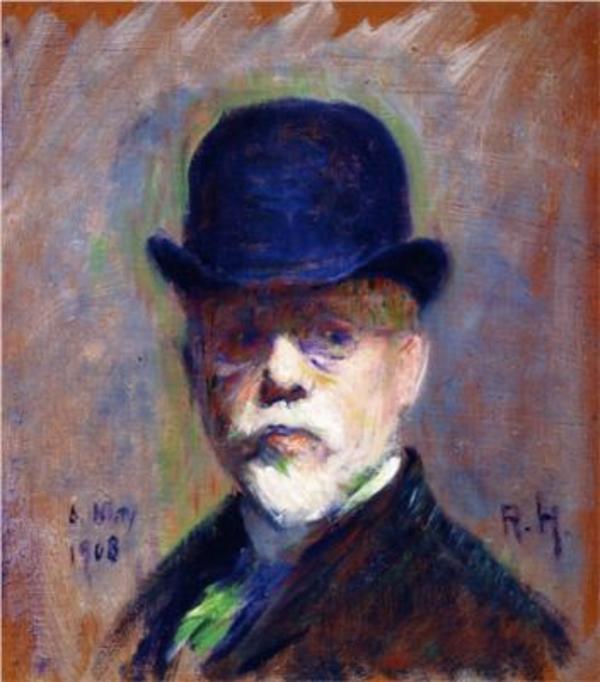

On 22 May 1885 Harris was married. After a few days in Quebec City, the couple continued their honeymoon in England. France, Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands before returning to Canada on 18 August. As earlier, Harris painted tirelessly. His splendid portraits of Thomas Workman* and Sir Hugh Allan*, his Bessie in her wedding gown (1885), and his own Self-portrait of the same period are but four examples of the best of his work; the poses are perfectly balanced to match the physical proportions of the sitters. In 1885–86 he painted two of his most popular canvases, Harmony and The meeting of the school trustees. The second, sensational because of its feminist theme, portrayed a young woman teacher addressing a group of older male trustees.

In addition to hundreds of portraits of distinguished Canadians, Harris painted numerous observant studies of models, native people, and youngsters. From Sir Hugh Allan onwards, he charged the not inconsiderable fee of $500; at the height of his career the fee was increased to $600. As well as being able to provide assistance to members of his family, he could now travel abroad regularly with Bessie. In 1906 they resided in Munich and Italy. Their final European visit, to Paris, Bern, and Étaples, France, was in 1911, after which their travels were confined to New England, Quebec, and the Maritimes. Travel and residence abroad made Harris increasingly aware of his identity as a Canadian. His talks to the Art Association of Montreal and other organizations developed the theme that Canadian art had an identity separate from that of other countries. He was probably among the first to undertake research into the relation between Canadian art and its British and European influences.

No better evidence of Harris’s qualifications and the high esteem in which he was held by his peers exists than his appointment, through the academy, to organize the Canadian collection for the Columbian exposition at Chicago in 1893. That same year he was nominated president of the academy. He had refused the nomination in April 1890 but now felt obliged to accept. He would remain in office for 13 years, the longest term yet served by any president. During his tenure, he put its affairs on a more businesslike footing. Another goal was to stimulate a greater interest in Canadian art on the part of the general public, which was inclined to treat artists less fortunate than himself with disdain or indifference. Following his success in Chicago he pressed on with his view that Canadian participation in international exhibitions must be encouraged by the financial support of the government. He wrote and signed three petitions to Sir Wilfrid Laurier requesting student scholarships for study abroad and financial assistance for the academy itself as well as for Canadian participation in the universal exposition in Paris, to be held in 1900. Another petition dealt with the lotteries of the Art Union of Canada; originally organized to raise money for the acquisition of paintings for a national gallery, they had turned into outright gambling from which artists received no benefits whatsoever. All four petitions were ignored, but Harris continued lobbying and in time his requests were granted. Having opened its coffers, the government saw that Canadian art was represented at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, N.Y., in 1901 and at the Louisiana Purchase exposition in St Louis, Mo., in 1904. Harris won a gold medal in Buffalo and an honourable mention and a gold medal at St Louis. He had received an honourable mention in Paris in 1900. Organizing the Canadian display for the exposition of 1904 was his final major undertaking before stepping down from the presidency of the academy two years later. In 1902, in recognition of his service to Canadian art, he had been made a cmg.

It is ironical that Harris should be known to generations of Canadians through a painting destroyed by fire and seen by them only in photographs and reproductions. In October 1916 he was requested to make another of the same subject. He refused, fearing that the effort required to execute the commission would prevent him from accepting others and would adversely affect his health. Instead he suggested that “the Government would do well to purchase [the original cartoon] drawing,” for $2,000, in his words, a “very moderate” price. The drawing was not, of course, to be copied. It is now in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada.

Years of hard work and administration combined with poor health and eyesight did not stop him from sketching, although in his later years the results were far from acceptable. After a holiday in Prince Edward Island in the summer of 1918 he returned to Montreal and began negotiations for a proposed portrait of Francis Lovett Carter-Cotton. It was not to be. Harris was almost totally blind and could barely move from his sofa. He died on 27 Feb. 1919.

In his introduction to the Harris Memorial Exhibition of 1919 a friend and former student, George Agnew Reid*, noted Harris’s splendid service to art and the fact that he was a kind critic, always ready to praise that which was good in the work of a fellow artist. “Much more might be said of the work and worth of Robert Harris,” he continued, “but modesty was one of his distinguishing traits, and we hesitate to give him that praise which he so richly merited, knowing that to him the work was everything, the worker nothing.”

[Robert Harris is the author of a volume of poetry published posthumously under the title Verses by the way, from an artist’s sketch book (Charlottetown, 1920). His paintings and sketches are found in various private collections in Canada and the United States as well as in many of the major public art galleries in Canada, among them the Confederation Centre Art Gallery and Museum (Charlottetown) and the National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa). The bulk of Harris’s family correspondence is preserved in the Harris family papers in the archives of the Confederation Centre Art Gallery and Museum; several additional letters are found in NA, MG 29, D88.

Harris’s works have been the subject of several exhibitions. Among the more useful of the resulting catalogues are Robert Harris, 1849–1919 (Confederation Centre, 1967), and the author’s Robert Harris (1849–1919) (National Gallery of Canada, 1973). The present biography is based on the author’s two full-length studies, Robert Harris, 1849–1919: an unconventional biography (Toronto and Montreal, 1970) and Island painter: the life of Robert Harris (1849–1919) (Charlottetown, 1983). m.w.]. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). W. [G.] Colgate, Canadian art, its origin & development (Toronto, 1943; repr. 1967). A dictionary of Canadian artists, comp. C. S. MacDonald (7v. to date, Ottawa, 1967– ). J. R. Harper, Painting in Canada, a history ([Toronto], 1966). Frank MacKinnon, “Robert Harris and Canadian art,” Dalhousie Rev. (Halifax), 28 (1948–49): 145–53. N. [McF.] MacTavish, The fine arts in Canada (Toronto, 1925; repr., [intro. Robert McMichael], 1973). Royal Canadian Academy of Arts: exhibitions and members, 1880–1979, comp. E. de R. McMann (Toronto, 1981). B. K. Sandwell, “Most famous Canadian picture and its painter: Robert Harris, r.c.a., and ‘The Fathers of Confederation,’” Saturday Night, 9 July 1927: 5. Rebecca Sisler, Passionate spirits; a history of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, 1880–1980 (Toronto, 1980). Some papers from an artist’s life (Robert Harris Memorial Gallery and Public Library, Charlottetown, [1919?]). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell). R. C. Tuck, Gothic dreams: the life and times of a Canadian architect, William Critchlow Harris, 1854–1913 (Toronto, 1978). Moncrieff Williamson, “Robert Harris and The Fathers of Confederation,” National Gallery of Canada, Bull., 11 (1968): 8–21.

Cite This Article

Moncrieff Williamson, “HARRIS, ROBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/harris_robert_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/harris_robert_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Moncrieff Williamson |

| Title of Article: | HARRIS, ROBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | April 2, 2025 |