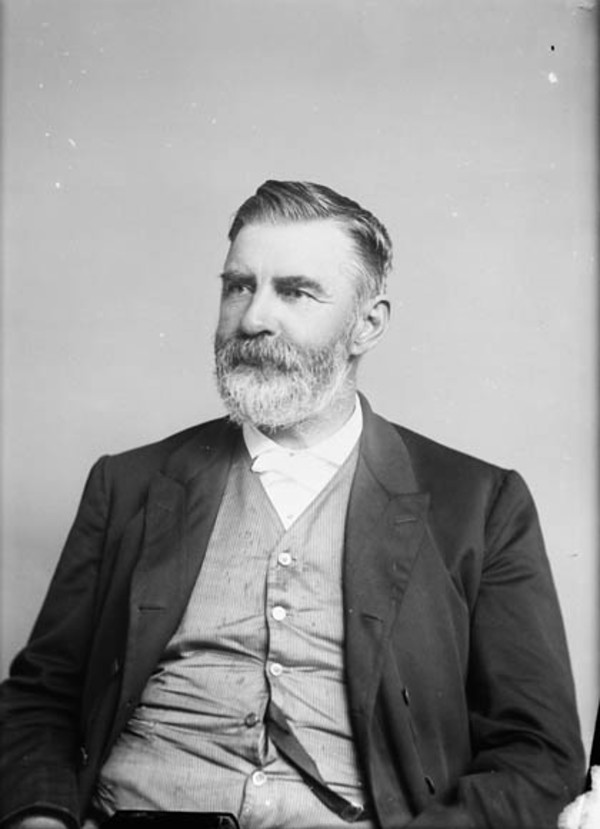

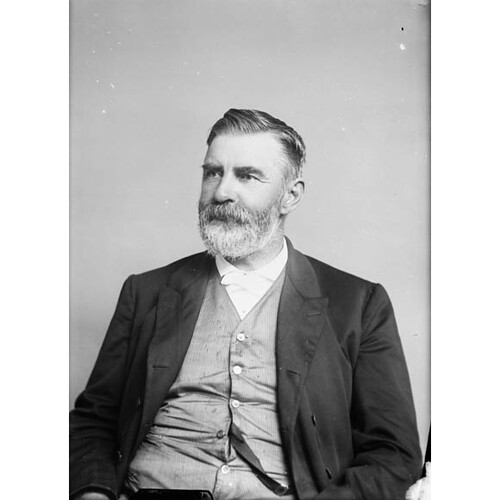

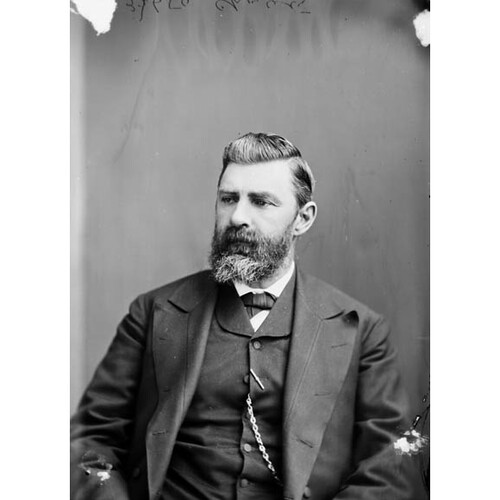

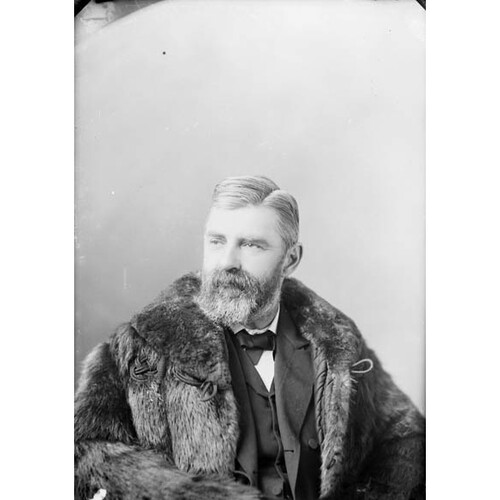

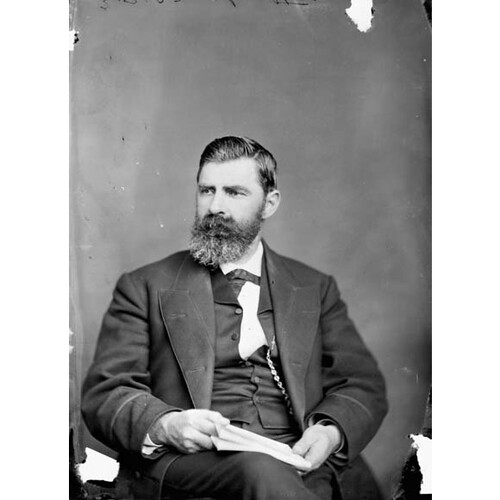

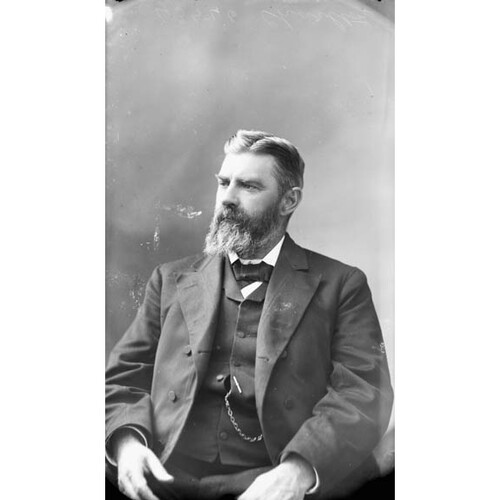

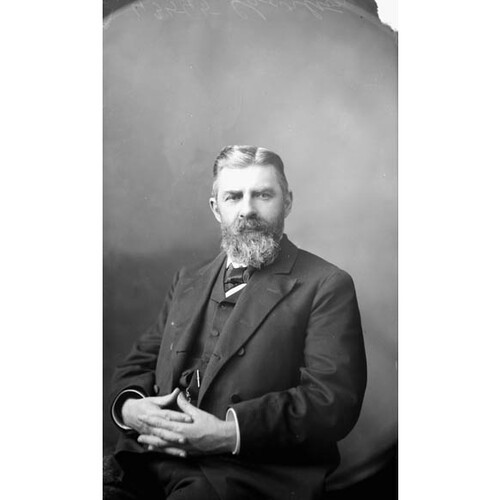

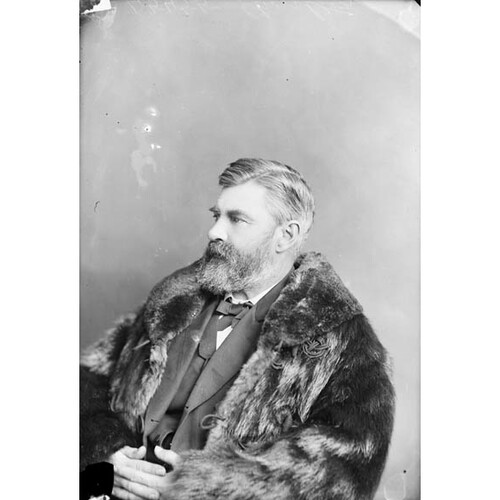

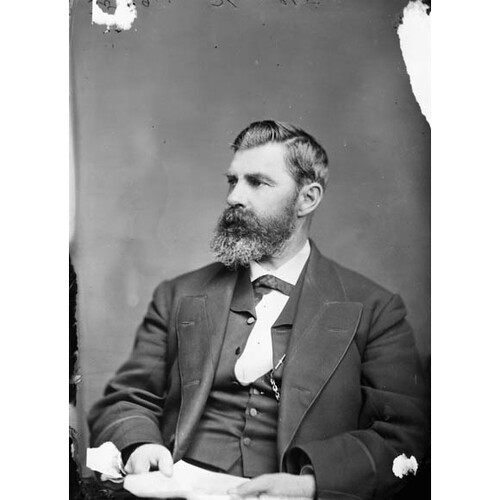

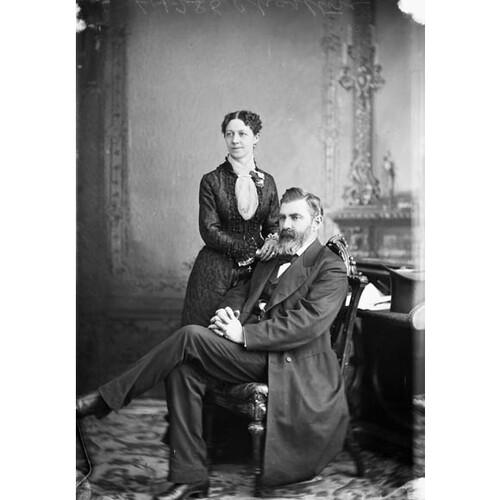

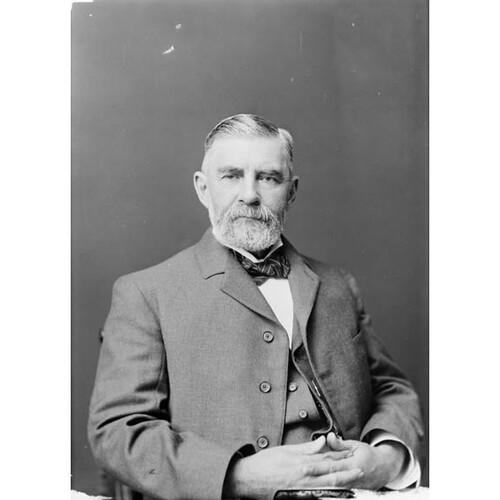

CHARLTON, JOHN, farmer, businessman, politician, office holder, and social reformer; b. 3 Feb. 1829 in Garbuttsville (Garbutt), N.Y., eldest son of Adam Charlton and Ann Gray; m. 1 Nov. 1854 Ella (Ellen) Gray in Charlotteville Township, Upper Canada; they had no children; d. 11 Feb. 1910 in Lynedoch, Ont.

Born on the family farm at Garbuttsville, near Caledonia, John Charlton relocated with his parents in 1832 to Cattaraugus County, N.Y. His father continued farming and was employed as financial manager for the Holland Land Company in Ellicottville. Charlton was educated at the McLaren Grammar School in Caledonia and at the Springville Academy. In addition to working on his father’s farm, he learned to set type at the Cattaraugus Whig of Ellicottville. After a year in a general store there, he read law briefly and may have studied medicine for a short period. In 1846 he travelled by lumber raft down the Allegheny and Ohio rivers to Cincinnati, Ohio.

In 1849 Charlton and his family moved to Upper Canada, settling on a farm south of Ayr, in Waterloo County. For the next four years he farmed with his father; in his spare time he organized a circulating library and a debating society. He had come to Canada with the intention of leaving for the western United States as soon as possible. In 1853, as he was planning to migrate to Minnesota, he instead accepted an offer from George Gray (a relative of his mother and his future father-in-law) to join him in opening a general store in Norfolk County at Wilson Mills, near the Lynedoch post office. The white pine in the area was of high quality and, in addition to selling goods, Gray and Charlton traded in timber. With the advent of reciprocity between the United States and Canada in 1854, their firm soon entered the timber business on a formal basis, in association with Smith and Westover of Tonawanda, N.Y.

Business commitments made it impossible for Charlton to join his parents and brothers when, in 1855, they left for Iowa but soon afterwards he visited them. Although he considered himself a protectionist in trade, the trip convinced him that Canada needed better access to American markets so that it might share the commercial advantages enjoyed by Iowa and other western states. He now regarded Canada as equal or superior to the United States in most respects, and his sojourn in Iowa, he claimed, cured him of “western fever.”

In 1858 Charlton’s brother George returned from Iowa to replace him in the general store at Lynedoch, allowing John to devote more time to the timber business. Charlton became head of the Canadian operations of Smith and Westover the following year. He purchased the firm’s Canadian business in 1861, in partnership with James Ramsdell of Clarence, N.Y., and was joined at Lynedoch by another brother, William Andrew. He had bought out Ramsdell by 1865 and was in business on his own at Lynedoch and Tonawanda. In 1868 he was joined in the lumber and timber business by his brother Thomas. Their firm, J. and T. Charlton, would operate under this name until John Charlton’s death in 1910. In partnership with Alonzo Chesbrough of Suspension Bridge (Niagara Falls), N.Y., Charlton expanded his cutting operations into the United States, acquiring large tracts of pine in eastern Michigan.

Charlton had first held public office in 1856–57 as a Charlotteville Township councillor. His interest in politics was rekindled by the build-up to the American Civil War. In 1860 he delivered a lecture in Lynedoch – “Does the Bible sanction slavery?” – which brought him into prominence, and he continued to give it throughout the war. He believed the answer to his question was no, but felt that many Canadians, particularly Tories, sympathized with the Confederacy. Around 1866 he organized a circulating library and founded a debating society called the Lynedoch Lyceum. Local Tories accused it of treason for its frank debates on reciprocity and annexation to the United States.

In 1872 Charlton sought and received the federal Liberal nomination in Norfolk North, despite the objections of some Grits who argued that, as an American, he had “annexation proclivities” that would harm his chances of election. Returned to the House of Commons that year, he would hold Norfolk North until his resignation from politics in 1904. During this period the Liberals were in power from 1873 to 1878 and again from 1896. As a government backbencher in the 1870s Charlton served on the committee appointed to investigate Canada’s economic problems. On trade policy his shifting views reflected the divisions within his party [see Alexander Mackenzie*]. Despite his speeches in the house in favour of reciprocal trade with the United States, he could sympathize with those urban Liberals and manufacturers who, he believed, sought protective tariffs out of self-interest. By 1876 he was advocating an increase in duties to satisfy the party’s protectionist wing. In the two years before the federal election of 1878, however, he was a tireless campaigner for reciprocity, the policy supported by party leaders.

Charlton adopted this position at some cost: in attacking his views, Tory opponents again took aim at his American origin. In his unpublished autobiography Charlton recorded, “I was often made to feel the power over the Canadian mind, of narrow bigotry and senseless prejudice.” After the Liberal government’s defeat in 1878, Charlton continued to serve his party faithfully. By January 1882, with an election expected, he and George William Ross* had formed its committee on campaign literature. Publishing supplements for county newspapers from the office of the Ottawa Free Press, they selected extracts from “speeches pertinent to issues of the day and original contributions from members of the House.” In fact, Charlton later noted, he and Ross were the authors of much of this political boilerplate.

By the mid 1880s Charlton, a prominent member of the Canadian Forestry Association, had come to be known in the commons as “the member for Michigan” because of his forestry interests there and his agitation for commercial union with the United States [see Erastus Wiman]. In 1884 and 1885 J. and T. Charlton wound up its operations in Norfolk County and Michigan and began working limits on the north shore of Georgian Bay as a new source of supply for the firm’s factory at Tonawanda. In addition, Charlton and his brother William purchased limits at the headwaters of the Blind and Serpent rivers in the Algoma District. In 1888 Charlton was appointed chairman of the royal commission established by the Ontario government to examine the province’s mineral resources and their exploitation. In its report of 1890 the commission called for an end to “commercial belligerency” between Canada and the United States.

Charlton’s business took him to the United States several times a year, and he had cultivated connections in several state legislatures and in Washington. In 1890, after Canadian lumbermen had persuaded their federal government to remove duties on American lumber, in return for favourable American duties on Canadian lumber, Charlton lobbied successfully for additional reciprocal-trade concessions made possible by the McKinley tariff in the United States. He visited Washington again in 1892 and 1893, as a representative of the Liberal party, for further negotiations on the trade in forest products.

Although trade relations occupied much of Charlton’s time, his religious beliefs and strong convictions about moral reform also found frequent expression, both commercially and politically. A member of the Presbyterian Church from the 1850s and a confirmed Sabbatarian, he did not permit labour in his lumber camps on the sabbath and he managed to confine his business travels to the other six days of the week, returning home to Lynedoch by Sunday. For Charlton public morality and national strength were most definitely connected. In parliament in 1879 he seconded the motion by Thomas Christie calling for stricter observance of the Lord’s Day by agencies of the dominion government. Charlton argued that Britain, as an avowedly Christian nation, had enacted similar laws to secure religious liberty. Within a decade the call in Canada had escalated to a drive for a national Lord’s Day observance act. In 1888 Charlton was elected vice-president at the inaugural meeting in Ottawa of the Lord’s Day Alliance, which drew support from Presbyterians. In 1894 Charlton argued in the commons that to prevent great social upheaval, including labour violence, it was necessary to apply “Christian principles . . . and the first step to take in applying them is to recognize God’s law, that the Sabbath Day is to be remembered and kept holy, and the labourer is to be secured in the possession of his right to enjoy . . . a day of rest.”

On 20 Feb. 1882, driven by “a profound sense of public duty” and evidently drawing on the views of his church and on legislation in Britain and some American jurisdictions, Charlton had introduced a bill in parliament to provide for the punishment of adultery and seduction under criminal law. The bill proposed prison sentences for men convicted of having sexual intercourse with girls under 16, for teachers who seduced female students, and for men who seduced women through the promise of marriage. Charlton noted that when introduced the bill was “scarcely accorded a hearing, and was made the butt of ridicule and discourteous remarks.” Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* facetiously observed that the legislation would cause thousands of young men to leave the country. The bill died on the order paper at the dissolution of the house for the election of 1882. Charlton reintroduced it in 1883, only to see the section on adultery removed by a select committee, and the amended bill laid over by the Senate. The following year it was again blocked in the upper house. Bolstered by a resolution of the Presbyterian General Assembly in 1885 that advocated extended protection against seduction, Charlton put the bill forward once again in 1886. “The degradation of women is a crime against society,” he said. “The pure Christian home is the only safe foundation for a free and enlightened state. Vice in the shape of social immorality is the greatest danger that can threaten the state.” At the request of John Sparrow David Thompson*, the minister of justice, the bill was referred to a special committee for modifications proposed by his department. Designed to mollify opponents of the bill, the amendments weakened its force, requiring, as they did, corroborating evidence for charges of seduction. The amended bill, which became known as the Charlton Seduction Act and was passed by the house on 14 April and by the Senate on 13 May, provided that a man convicted of sexual intercourse with a girl under 16 be sentenced to three years in prison. Although the act would lead to relatively few prosecutions, it did establish Charlton’s reputation as a moral reformer and brought gender relations further into the sphere of criminal law.

Charlton’s religion also influenced his views on French-English relations in Canada. In 1886 he voted with the Tories against the motion by Liberal leader Edward Blake* condemning the execution of Louis Riel*. Shortly after Blake’s five-and-a-half-hour discourse on the subject, Charlton, himself a logical and concise speaker, had proposed a motion to limit the length of speeches in the house. He also angered Blake’s successor, Wilfrid Laurier*, when in 1889 he thwarted Laurier’s attempts to limit his role in the parliamentary debate over the Jesuits’ Estates Act [see Honoré Mercier*]. Supporting the call for federal disallowance of this Quebec statute, Charlton declared: “Now these are British provinces. The design was that these should be Anglo-Saxon commonwealths.” Thus “the tendency to foster an intense spirit of French nationality” should be resisted. As one of only 13 mps to vote in favour of disallowance – the “noble thirteen,” in the words of Macdonald – Charlton found himself increasingly estranged from the Liberal leadership. Indeed, he shared the platform with Conservative maverick D’Alton McCarthy* at a meeting to honour the “noble thirteen” in Toronto on 22 April 1889. Although he became a member of the Equal Rights Association, formed in June under the direction of William Caven, Charlton ultimately refused to sign its manifesto. He resented McCarthy’s partisan attacks on the Ontario Grits and, after assuring Premier Oliver Mowat of his support in the provincial election campaign of 1890, he accused McCarthy of trying to turn the ERA into a “donkey-engine of Toryism.” Nevertheless, Charlton had come to believe that the Liberal party was now only the lesser of two evils. With “a French Catholic leader and under the manipulation of such unscrupulous machine politicians as J. D. Edgar* . . . I have not the utmost confidence in the future of the Reform party,” he wrote. At the same time his own credibility in parliament may have diminished. On drawing the commons’ attention in 1890 to incidents in which French Canadian mobs had driven a female Protestant evangelist back across the Ottawa River from Hull, Charlton was attacked by both Macdonald and Blake for trying to score political points.

In 1895–96 public debate in Canada was dominated by Manitoba’s elimination of public funding for Catholic schools. Siding with the provincial Liberal government of Thomas Greenway in its opposition to remedial legislation, Charlton encouraged Laurier to do the same. Despite their differing views on the question, Laurier and Charlton met in the spring of 1896 to discuss the impending federal election. Laurier, who believed that the Liberals stood a good chance of winning, asked Charlton if there was a cabinet position he would like. Charlton told him that he would prefer to be made commissioner to the United States. The Liberals were victorious in June and Charlton was accordingly dispatched to Washington to push free trade. The assignment, however, may have been only a means to satisfy the free-trade wing of the Liberal party, for its leadership was, in fact, moving away from reciprocity [see George Hope Bertram*]. Charlton returned in December, his mission foiled by re-emerging protectionist sentiment in both countries. In 1897 Charlton went back to Washington in an unofficial capacity to lobby against the Dingley tariff, which restored protective duties, particularly on forest products [see John Bertram], but he succeeded only in embarrassing the Laurier government. He was nevertheless appointed in 1898 to the joint Canadian-American high commission, where he encountered entrenched American resistance to tariff concessions.

By the time of the general election of 1900, Charlton had become deeply disillusioned with the Liberal party. He believed that it had failed to keep its promises on such matters as prohibiting the granting of land, timber, and mineral rights to mps and friends, an issue that had claimed his attention since the 1880s. He was bitter too over the influx of new faces into Laurier’s cabinet. Charlton made his feelings clear to his constituents, and in so doing won the support of many Conservatives. According to his autobiography, he made an agreement with the Tories whereby he was able to run unopposed in Norfolk North in return for his promise not to campaign for Liberals in other ridings. By 1904 ill health forced him to retire from politics, and he did not run for election that year. He had continued to be an active businessman. In 1899, with his brother William and Thomas Pitts, he had formed another timber company. The following year his early company, J. and T. Charlton, opened a sawmill in Collingwood, Ont. He died in 1910 as a result of a stroke at his home in Lynedoch.

Politics in 19th-century Canada was about business and religion. John Charlton’s career reflects that fact. As a lumberman who sold most of his product in the United States, he naturally sought better access to the American market. As a Presbyterian, he became the parliamentary agent for his church, pressing for legislation which reflected its stance on seduction and the sabbath. Although the Charlton Seduction Act of 1886 was a weak version of his original bill, he viewed it as his major legislative achievement. In many ways, Charlton was an outsider: his concern for the protection of women met with ridicule, he was frequently subjected to disparaging remarks about his American origin, and he became increasingly isolated from the mainstream of the Liberal party, both as a Protestant stalwart and as a free trader. Charlton’s politics flowed from his personal interests, but throughout most of his career those who shared his concerns were seldom in power.

The most important primary sources of information on John Charlton are his papers, held at the Univ. of Toronto Library, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, ms Coll.110. The collection consists of Charlton’s diaries and a typescript autobiography, approximately 1,000 pages long, based on the diaries.

Charlton’s publications include numerous speeches, listings for which appear in CIHM Reg. and Canadiana, 1867–1900. A collection, Speeches and addresses, political, literary and religious, was issued at Toronto in 1905. He is also the author of an article, “Canadian trade relations with the United States,” in Canada, an encyclopædia (Hopkins), 1: 371–78.

Globe, 14 Feb. 1910. C. [B.] Backhouse, Petticoats and prejudice: women and law in nineteenth-century Canada ([Toronto], 1991). R. C. Brown, Canada’s National Policy, 1883–1900: a study in Canadian-American relations (Princeton, N.J., 1964). R. C. Brown and Ramsay Cook, Canada, 1896–1921: a nation transformed (Toronto, 1974). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1885–86. Canada Lumberman and Woodworker (Toronto), 30 (1910), no.5: 27. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Paul Crunican, Priests and politicians: Manitoba schools and the election of 1896 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1974). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. Karen Dubinsky, “‘Maidenly girls’ or ‘designing women’? The crime of seduction in turn-of-the-century Ontario,” Gender conflicts: new essays in women’s history, ed. Franca Iacovetta and Mariana Valverde (Toronto, 1992), 27–66. [J. J.] B. Forster, A conjunction of interests: business, politics, and tariffs, 1825–1879 (Toronto, 1986), 152. J. F. P. Laverdure, “Canada on Sunday: the decline of the sabbath, 1900–1950” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1990). J. R. Miller, Equal rights: the Jesuits’ Estates Act controversy (Montreal, 1979). Nelles, Politics of development. R. W. Winks, Canada and the United States: the Civil War years (rev. ed., Montreal, 1971), 234.

Cite This Article

Thomas H. Ferns and Robert Craig Brown, “CHARLTON, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/charlton_john_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/charlton_john_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Thomas H. Ferns and Robert Craig Brown |

| Title of Article: | CHARLTON, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |