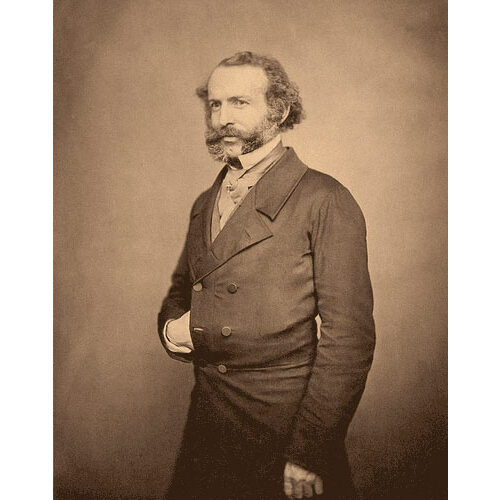

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

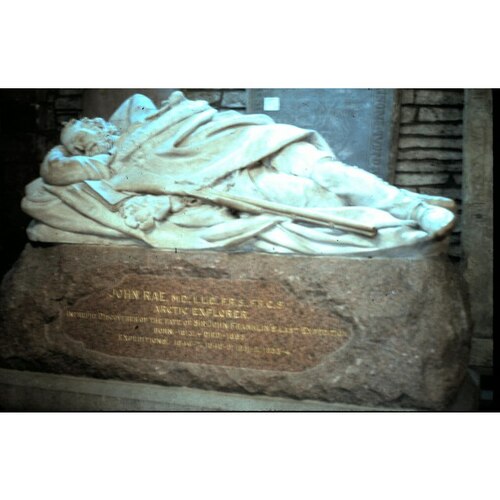

RAE, JOHN, surgeon, fur trader, explorer, and author; b. 30 Sept. 1813 at the Hall of Clestrain in the parish of Orphir, Orkney Islands, Scotland, sixth child and fourth son of John Rae and Margaret Glen; m. 1860, probably on 25 January, in Toronto, Catherine Jane Alicia Thompson, daughter of Major George Ash Thompson of Ireland; they had no children; d. 22 July 1893 in London, and was buried at St Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall, Scotland.

John Rae’s father was the local agent for the Hudson’s Bay Company in Orkney. Young John spent his boyhood there, receiving his education at home from a private tutor. As a boy he learned to sail small boats and to shoot, and he spent much of his time outdoors, on expeditions to the hills and moors and rock-climbing on the sea cliffs. It was these activities, “often thought useless,” which were of great service to him later in life. In 1829 he went to Edinburgh to study medicine, and he qualified as a licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh in April 1833.

That summer, by which time two of his older brothers had entered the service of the HBC, John was appointed surgeon to the HBC ship Prince of Wales for the voyage from England to Moose Factory (Ont.). On the way back the ship was unable to enter Hudson Strait (N.W.T.) because of ice, and it had to winter at Charlton Island in James Bay. Scurvy broke out among the passengers and crew, and two of the crew died. The other sufferers were cured when, in the early spring, Rae accidentally found cranberries that had been preserved under the snow.

In July the Prince of Wales sailed for Moose Factory and, when it left for England the following month, Rae remained behind as surgeon to the post, “thinking from what I saw that I should like the wild sort of life to be found in the Hudson’s Bay Company’s service.” He spent the next ten years at Moose Factory. Although at first he declined an offer from HBC governor George Simpson* to serve as both clerk and surgeon, he soon found there was not enough medical work to keep him occupied, and he became more and more involved in the general trading activities of the post. He also continued his outdoor pursuits and learned from the Cree their methods of travelling and hunting. In particular he became an expert in snowshoeing, and was described by HBC clerk Robert Michael Ballantyne as “the best and ablest snow-shoe walker not only in the Hudson Bay Territory but also of the age.”

In 1844 Rae again attracted the attention of Sir George Simpson when the HBC governor was looking for a man to lead an expedition to survey the part of the northern coastline of Canada not explored by Peter Warren Dease* and Thomas Simpson in 1837–39. Rae was chosen and, leaving Moose Factory in 1844, he travelled by canoe to Upper Fort Garry (Winnipeg) to receive instruction in surveying. George Taylor, who was to have been his teacher, died soon after Rae reached the fort. In January–March 1845 Rae travelled on foot to Sault Ste Marie, Upper Canada, covering the distance of 1,200 miles from Upper Fort Garry in two months. From there he proceeded to Toronto and obtained the necessary instruction from Lieutenant John Henry Lefroy*, who was then in charge of the Toronto observatory.

Between 1846 and 1854 Rae made four expeditions to the Arctic, during which he travelled more than 10,000 miles on foot or in small boats, and surveyed about 1,800 miles of coastline. On his first voyage he left York Factory (Man.) in June 1846 with ten HBC men and two small boats. At Fort Churchill (near Churchill) two Inuit interpreters, Ooligbuck* and his son William, joined the expedition. After sailing up the west coast of Hudson Bay and through Roes Welcome Sound to Repulse Bay (N.W.T.), Rae made the first crossing of the isthmus at the base of Melville Peninsula, now called Rae Isthmus. Since the lateness of the season prevented him from making further progress, he returned in August to Repulse Bay, where he built a stone house, Fort Hope, and prepared to winter. The party spent the remaining weeks before winter set in hunting, fishing, and gathering Andromeda tetragona (a bog plant) for fuel, so that they were largely self-sufficient. In the spring of 1847 Rae and his men, the first exploring party to have wintered on land on the Arctic coast, travelled westward and surveyed the shores of Committee Bay, Simpson Peninsula, and Pelly Bay, all named by Rae. He reached Lord Mayor Bay, which had been discovered by John Ross* in 1830, and he saw that Boothia was a peninsula joined to the mainland by a narrow isthmus. After returning briefly to Fort Hope, he set out again on 13 May and travelled northward up the west coast of Melville Peninsula as far as Cape Ellice (Cape Parry), about 19 miles from Fury and Hecla Strait. In September the party returned all fit and well to York Factory, where Rae received news of his promotion to chief trader. Before leaving for a visit to England, he wrote three letters to Governor Simpson and an official report to the London committee of the HBC describing his travels.

While in London, Rae met Sir John Richardson* who, impressed by Rae’s account of his voyage, invited him to serve as second in command on his search for the Arctic expedition led by Sir John Franklin*, which had not been heard from since the summer of 1845. In the spring of 1848 Richardson and Rae sailed to New York and continued by steamer to Sault Ste Marie. The expedition set out by canoe from there on 4 May and reached the mouth of the Mackenzie River 96 days later. Proceeding eastwards along the coast as far as Cape Kendall (on Coronation Gulf), the men abandoned their canoes and travelled overland to winter at Fort Confidence on Dease Bay (Dease Arm), where John Bell*’s advance party earlier that year had built winter quarters for them. The following summer, 1849, while Richardson sailed for England, Rae with a party of six men returned to the Arctic coast and tried to cross Dolphin and Union Strait to Wollaston Land (Wollaston Peninsula), but they were prevented by the ice. The party went back to Fort Confidence and then made its way to Fort Simpson on the Mackenzie River.

Rae did not revert easily to his duties as a fur trader; as he wrote in November 1849 to James Hargrave* at York Factory, “It is certain that I never was intended for a man of business and my avocations for the last 4 or 5 years have driven the little I did know about accounts and etc. quite out of my head.” Nevertheless in the fall of 1849 he took charge of the Mackenzie River district, with headquarters at Fort Simpson. There he was joined for the winter of 1849–50 by Lieutenant William John Samuel Pullen*, whose party had abandoned its search for Franklin.

Rae and Pullen left Fort Simpson together in June 1850, Rae on his way to Methy Portage (Portage La Loche, Sask.) with the season’s collection of furs and Pullen homeward-bound. They received instructions from Sir George Simpson and the Admiralty to continue the search for Franklin. Pullen and his party returned immediately to the Arctic coast. Rae continued to Methy Portage, where he learned of his promotion to chief factor, and then travelled to Fort Confidence. There he spent the winter of 1850–51 preparing for his third Arctic expedition.

On 25 April 1851 Rae left Fort Confidence on foot and, using dog-sleds, reached the Arctic coast early in May. While awaiting the arrival of two boats built to his own design, he crossed Dolphin and Union Strait on the ice to Wollaston Land and, over the next three weeks, completed the survey of the southern coastline of Victoria Land (Victoria Island) begun by Dease and Simpson. Having ascertained that no strait existed between Wollaston and Victoria lands at this point, he made his way back to the Kendall River, where he was met by the party from Fort Confidence with the two boats. Setting out again in mid June, he descended the Coppermine River to the coast and sailed east along the south shore of Victoria Land as far as Collinson Peninsula. He tried to cross Victoria Strait to King William Land (King William Island), but was prevented from doing so by closely packed ice. On his return journey he found two pieces of wood in Parker Bay that probably came from Franklin’s ships, which had been beset in Victoria Strait, but he did not obtain any definite information about them or their crews. Upon his return to Fort Confidence in September, Rae was granted leave for another visit to Britain.

Rae’s fourth expedition was sponsored by the HBC, at his own suggestion, to complete the survey of the mainland coast of North America. Only a small portion remained unexplored: from the western end of Bellot Strait, discovered in 1852, to the Castor and Pollux River, the farthest point east reached by Dease and Simpson. Rae hoped to confirm his 1847 discovery, which the Admiralty had not yet accepted, that Boothia was a peninsula. He left York Factory in June 1853 with two boats and twelve men, intending to sail up Chesterfield Inlet to its head and then to travel overland to the Great Fish (Back) River, which he would descend to the coast. On the way up Chesterfield Inlet, Rae entered a river which he named Quoich, and he spent ten days exploring it. When he discovered that it did not lead him in the direction he wished to go, he sent six of his men and one boat back to Fort Churchill and proceeded to his old base at Repulse Bay for the winter. Once again he provided food for his party by hunting and fishing during the fall. This time they wintered in snow houses, which he had learned to build and which they found more comfortable than the stone house which was still standing.

On 31 March 1854 Rae set off on his journey westward, making for the isthmus of Boothia Peninsula. At Pelly Bay on 21 April he met an Inuk and from him heard about a party of white men who, four years earlier, had perished from starvation near the mouth of a large river a long distance to the west. This information did not, however, induce Rae to abandon the object of his journey. He continued westward until he reached Dease and Simpson’s cairn at the Castor and Pollux River, and then spent nine days travelling northward up the west coast of Boothia, discovering Rae Strait and showing that King William Land was an island. On his return to Repulse Bay he was visited by more Inuit, from whom he learned the details of the tragedy that had befallen the party of white men, and he was able to identify the site of which the Inuit spoke as the vicinity of the Montreal Islands at the mouth of the Great Fish River. The Inuit also sold Rae articles which he could identify as having belonged to members of the lost expedition: inscribed silverware and Franklin’s Royal Hanoverian Order. Rae and his party returned to York Factory on 31 Aug. 1854 and Rae himself sailed for England on 20 September.

When Rae reached England with his news of Franklin’s party, he became the subject of an unpleasant controversy. In his report, which the Admiralty immediately made public, he included a statement by the Inuit that the last survivors of the stricken crews had resorted to cannibalism before perishing. That officers and men of the Royal Navy should be accused of such a deed was unthinkable in the mores of Victorian England. Rae was criticized because he had not gone to the scene of the tragedy to confirm the story, and he was accused of having rushed home to collect the £10,000 offered by the British government to anyone who ascertained the fate of Franklin and his party. Rae defended the credibility of the Inuit accounts and insisted he had not received sufficient information to locate the site of the tragedy until it was too late in the season to continue the search. He wrote to the Admiralty claiming the reward, but several people, including Lady Franklin [Griffin*], protested that he had not fully determined the fate of the men, and objected that premature payment would hinder further efforts to do so. There were other claimants to the reward, including Dr Richard King* and William Penny, and so the controversy continued until July 1856, when Rae and his men finally received it. Rae was given £8,000, and £2,000 was divided among his men. Subsequent discoveries made by Francis Leopold McClintock* in 1859 and later by other expeditions confirmed in all essential points the story which Rae had brought back in 1854.

Rae retired from the HBC in 1856 but early the next year he gave evidence on behalf of the company to the select committee set up by the British House of Commons to inquire into the company’s activities [see Sir George Simpson]. Thereafter he went to Upper Canada and from 1857 to 1859 made his home in Hamilton, where his brothers Richard Bempede Johnstone Honeyman and Thomas were in business. John was a founding member and the second president of the Hamilton Association, which sought to promote the advancement of literature, science, and art. In 1858 he accompanied Edward Ellice* on a trip through the United States, and the following year he travelled with the Earl of Southesk on a hunting expedition from St Paul, Minn., to Upper Fort Garry.

After his marriage in 1860 Rae returned to England. Later that year he was employed by the HBC to conduct the overland part of a survey for a telegraph line between Britain and America through Scotland, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, and Greenland. The following year he again travelled to Rupert’s Land. Although primarily on a hunting trip Rae surveyed some new territory in the southern part of present-day Saskatchewan and Alberta. In 1865 he carried out another survey on behalf of the HBC, for a telegraph line from St Paul to Vancouver Island. He travelled by way of Upper Fort Garry, followed the Carlton Trail to Fort Edmonton (Edmonton, Alta), and then crossed the Rocky Mountains by the Yellowhead Pass. Canoeing down the Fraser River as far as Fort Alexandria (Alexandria, B.C.), he visited the Cariboo gold-fields and then continued to Victoria.

After that journey Rae settled in London, but he made frequent visits to his native Orkney. He continued to take an active interest in British North America and the Arctic, and he was severely critical of the plans and the equipment for the British North Polar expedition of 1875–76 led by Captain George Strong Nares. After the expedition returned, he gave evidence to the committee set up by the Admiralty to inquire into the outbreak of scurvy among the sledging parties. From 1879 Rae was involved in the controversy over the relative merits of the route through Hudson Bay and that by the Great Lakes and the St Lawrence River for exporting grain from the prairies. On the basis of his experience Rae strongly supported the Great Lakes route. In his later years he continued to fight an ongoing battle with the Hydrographic Office of the Admiralty and with Sir Clements Robert Markham, secretary of the Royal Geographical Society, because of their refusal to acknowledge the discoveries made in the Arctic by himself and by other fur trader explorers, notably Dease and Simpson. Rae visited Canada for the last time in 1882, probably in connection with the Canada North West Land Company, of which he was a director. After his return to Britain he served on the council of the Royal Colonial Institute. A first-class shot, he represented the London Scottish Regiment, in which he was long a volunteer, in the annual shooting competition at Wimbledon (London) and later at Bisley, Surrey.

Rae received many honours. He was awarded the Founder’s Gold Medal of the Royal Geographical Society in 1852 for his discoveries of 1846–47 and 1851. In 1853 he was given an honorary md by McGill College, Montreal, and in 1856 the University of Edinburgh made him an lld. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1880. His Narrative of an expedition to the shores of the Arctic Sea, in 1846 and 1847 appeared in 1850, and he published numerous papers describing his travels, the Inuit and First Nations people he encountered, and the natural history of the Arctic. His unfinished autobiography was published in 2018.

In his lifetime Rae was a controversial figure. His adoption of native methods of travel in the Arctic was disapproved of by the Royal Navy, and his insistence on putting forward his point of view at every opportunity did not endear him to the establishment. He was, however, accepted as a friend by the Inuit, for whom he had great admiration. Defending the HBC’s treatment of the indigenous people, he made scathing remarks about naval officers and others who formed snap judgements after spending only a short time in the company’s territories: “These self-sufficient donkeys come into this country, see the Indians sometimes miserably clad and half-starved, the causes of which they never think of enquiring into, but place it all to the credit of the Company.” In the 20th century Rae has been recognized as an innovator in techniques of survival in the north, and as the forerunner of the great Arctic explorers Roald Amundsen and Vilhjalmur Stefansson*, both of whom acknowledged their debt to him.

John Rae’s publications include his Narrative of an expedition to the shores of the Arctic Sea, in 1846 and 1847 (London, 1850). A complete list of writings by and about him is found on pp.221–27 of the author’s full-length study Dr John Rae (Whitby, Eng., 1985). Rae’s HBC correspondence was issued as John Rae’s correspondence with the Hudson’s Bay Company on Arctic exploration, 1844–1855, ed. E. E. Rich and A. M. Johnson (HBRS, 16, London, 1953). His manuscript autobiography was acquired by the Scott Polar Research Institute (Cambridge, Eng.) in 1967 (ms 787/1); it is described in Alan Cooke, “The autobiography of Dr John Rae (1813–1893): a preliminary note,” Polar Record (Cambridge), 14 (1968): 173–77.

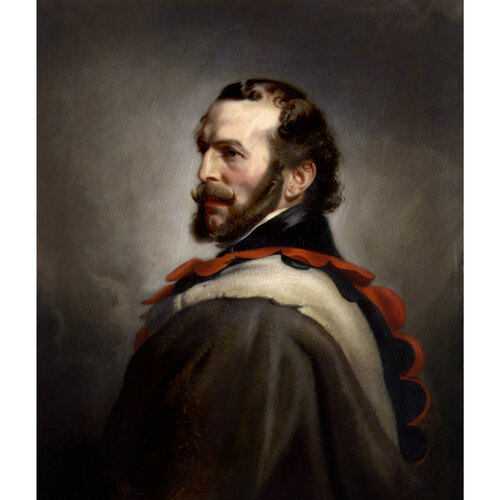

An oil portrait of Rae by Stephen Pearce is in the National Portrait Gallery (London); an engraving based on it is held by the PAM, HBCA, and appears on the frontispiece to John Rae’s correspondence. A bust of Rae made in 1866 by George MacCallum is at the Univ. of Edinburgh. A number of the relics from the last Franklin expedition which Rae bought from the Inuit in 1854 remained in his possession, and along with some of his personal effects and a small collection of Inuit and First Nations artefacts are found in the John Rae coll. at the Royal Scottish Museum (Edinburgh).

Revisions based on:

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “Scotland births and baptisms, 1564–1950,” John Rae, 14 Oct. 1813: www.familysearch.org (consulted 6 Dec. 2019). National Records of Scotland (Edinburgh), OPR Marriages, Cuthbert’s, 15 April 1804. J. Macdonald, Hamilton Association: inaugural address of J. Macdonald, esq., m.d., president ([Hamilton, 1881]). John Rae, John Rae, Arctic explorer: the unfinished autobiography, ed. William Barr (Edmonton, 2018).

Cite This Article

R. L. Richards, “RAE, JOHN (1813-93),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rae_john_1813_93_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rae_john_1813_93_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | R. L. Richards |

| Title of Article: | RAE, JOHN (1813-93) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |