Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BALLANTYNE, ROBERT MICHAEL, fur trader and author; b. 24 April 1825 in Edinburgh, son of Alexander Ballantyne and Anne Randall Scott Grant; m. 31 July 1866 Jane Dickson Grant, and they had six children; d. 8 Feb. 1894 in Rome.

Robert Michael Ballantyne’s father was a younger brother of James Ballantyne, the printer of Sir Walter Scott’s novels. When Scott unexpectedly went bankrupt in January 1826, Alexander Ballantyne, who had invested in his brother’s firm, shared in its reverses; thereafter his family lived in straitened circumstances. At age 16 Robert obtained a post with the Hudson’s Bay Company through the influence of relatives: Frances Ramsay Simpson*, wife of the company’s governor, Sir George Simpson*, and her sister Isobel Graham Simpson*, wife of the governor of Assiniboia, Duncan Finlayson*, were distant cousins. A contract dated 31 May 1841 appointed Ballantyne apprentice clerk for five years at a salary of £20 per annum.

Ballantyne arrived at York Factory (Man.) on 21 August, and ten days later left with a brigade for the Red River settlement. James Hargrave*, in charge of York, thought that the Simpsons would like Ballantyne to be near the Finlaysons, so the apprentice was posted to Upper Fort Garry (Winnipeg) as an accounting clerk. In June 1842 he was sent to Norway House and served there for a year. His third posting was to York Factory, where he continued as clerk until June 1845.

The initial assessment of Ballantyne by Letitia Hargrave [Mactavish*], James’s wife, in 1841 had been that he was “smart & very gentlemanlike & diverting,” but during his four years in Rupert’s Land his ineptitude sorely tried his superiors. In 1843 she wrote of him as “a useless little apprentice who can scarcely copy,” while her husband noted that he was as unfit to be an accountant “as to be an Archbishop of Canterbury.” Ballantyne himself was more interested in wilderness adventure than in accounts. The Hargraves could not know that his powers of observation and expression would later enable him to depict with accuracy life in the fur trade.

According to James Hargrave, during Ballantyne’s last winter at York he experienced “indifferent health, his constitution not suiting this inhospitable climate,” and he was therefore assigned to Lachine, Lower Canada. Ballantyne was disappointed to learn that he was to be trained as secretary to Governor Simpson, and requested a wilderness post. In January 1846 he set off with George Barnston* on snowshoes for the king’s posts along the north shore of the St Lawrence. The pair reached Tadoussac on 7 February. A month later Ballantyne was ordered to Îlets-Jérémie, and in April to Sept-Îles to relieve the incumbent. His five-year contract was to end in June but, as he had not given sufficient notice for a replacement to be found, he had to remain over the winter of 1846–47. He left Tadoussac on 9 May 1847 and later that month sailed from New York for Scotland.

Ballantyne’s literary career had its genesis in the boredom of isolated trading posts where he whiled away time by writing long descriptive letters to his mother. Later he recalled that at Sept-Îles there was no game to shoot and there were no books with which to amuse himself, “but I had pen and ink, and, by great good fortune, was in possession of a blank paper book fully an inch thick”; and so he set down his experiences in the trade. Following his return to Scotland, an elderly lady who had enjoyed reading his letters offered to finance a private printing of his recollections. In March 1848 Hudson’s Bay; or, every-day life in the wilds of North America . . . appeared.

Although Ballantyne, who had found employment with Edinburgh publishers, still had no intention of making a career of writing, his interest in Arctic exploration led him to revise Patrick Fraser Tytler’s Historical view of the progress of discovery on the more northern coasts of America . . . (Edinburgh, 1832). The new edition, aimed at a young audience, appeared in 1853 as The northern coasts of America, and the Hudson’s Bay territories . . . (London and Edinburgh).

On reading Hudson’s Bay, William Nelson, a publisher in Edinburgh, suggested to Ballantyne that he might write a book of juvenile literature, perhaps featuring some of his earlier adventures. In November 1856 Snowflakes and sunbeams; or, the young fur traders . . . was published in London, and Ballantyne was launched as an author of stories for boys. A year later he wrote another book with a Canadian locale; Ungava; a tale of Esquimaux-land was dated 1858 but appeared in November 1857, in time for the Christmas market. Ballantyne is believed to have obtained material for this book from Nicol Finlayson*, the founder of Fort Chimo (Kuujjuaq, Que.), who had lately retired to Scotland. The same Christmas saw the publication of The coral island; a tale of the Pacific Ocean.

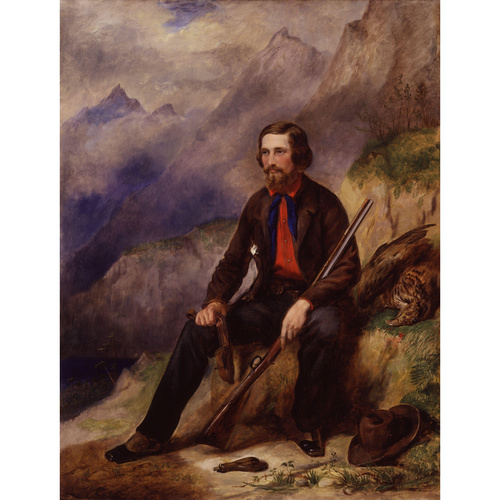

Over the next 30 years Ballantyne was credited with the authorship of 74 volumes containing 62 separate stories; if his illustrated nursery stories and his handbooks are included, he wrote more than 90 books. In the settings of his adventure stories, more than 20 of which deal with the Prairies, the Rockies, and the Arctic, he strove for verisimilitude. His plots are sometimes threadbare, the tone charged with Victorian morality; nevertheless, because of their action, his books enjoyed wide popularity with his juvenile audience. Many were illustrated by himself, for he was a draftsman and water-colourist who frequently exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy.

Ballantyne’s books ran through many printings, several were issued in new editions, and some remain in print. None of his later fictional works were as popular as the first three; unfortunately he did not benefit from their reprinting since he had sold the manuscripts outright to his first publisher, Thomas Nelson. In 1863 he went over to James Nisbet, a London publisher, who granted proper royalties. Ballantyne supplemented his income as an author by giving public lectures describing life in Rupert’s Land, using slides projected by a magic lantern and displaying mementoes of the fur trade.

About 1890 Ballantyne began to suffer vertigo and nausea, the onset of Ménière’s disease. He had increasing difficulty continuing his literary output. In October 1893, accompanied by a daughter, he set out for Rome to enter a medical clinic. Following his death four months later he was buried in Rome’s English cemetery. Through public subscription in Britain a tombstone was erected; much of the purse was received as pennies and sixpences from schoolboys to whom Ballantyne’s annual Christmas offerings of adventure had given such pleasure.

Robert Michael Ballantyne published recollections of his literary career in An author’s adventures, or personal reminiscences in bookmaking (London, [1893]). He wrote numerous works for boys, a good number of which went through several editions and reprintings. Detailed listings of his literary output are provided in Eric Quayle, R. M. Ballantyne: a bibliography of first editions (London, 1968), the British Library general catalogue, and the National union catalog.

PAM, HBCA, A.11/28: f.264d; A.32/21: f.77; B.134/c/62: f.341; B.134/g/20: 175; B.154/a/37: f.19; B.214/a/1; B.235/d/84: f.4; B.239/a/154; B.239/g/22; C.4/1: f.20d; D.5/11: f.238d; D.5/13: f.371d; D.5/14: f.94. Letitia [Mactavish] Hargrave, The letters of Letitia Hargrave, ed. Margaret Arnett MacLeod (Toronto, 1947). Times (London), 10 Feb. 1894. DNB. Eric Quayle, Ballantyne the brave; a Victorian writer and his family (London, 1967). J. W. Chalmers, “Ballantyne and the Honourable Company,” Alta. Hist. Rev., 20 (1972), no.1: 6–10.

Cite This Article

Bruce Peel, “BALLANTYNE, ROBERT MICHAEL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ballantyne_robert_michael_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ballantyne_robert_michael_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Bruce Peel |

| Title of Article: | BALLANTYNE, ROBERT MICHAEL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | April 29, 2025 |