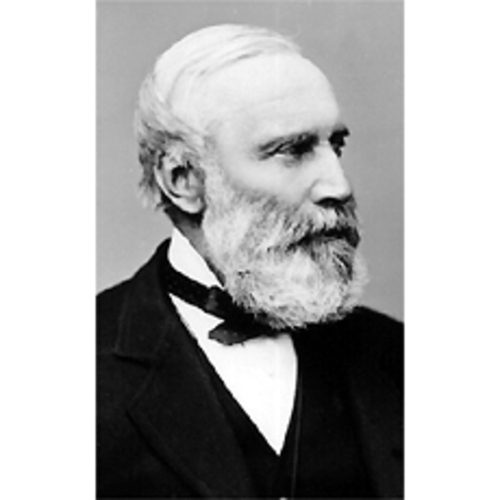

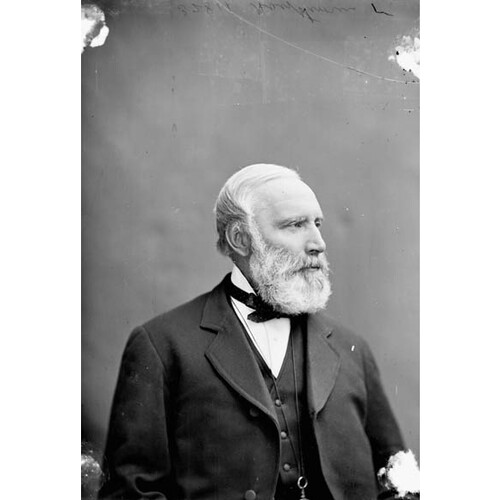

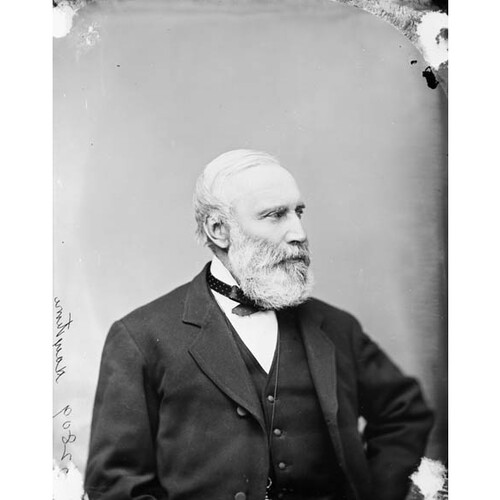

![Robert Poore Haythorne, premier of Prince Edward Island

Photograph by

William James Topley (1845–1930) Description Canadian photographer Date of birth/death 13 February 1845(1845-02-13) 16 November 1930(1930-11-16) Location of birth/death Montreal Vancouver Work location Ottawa, Ontario

, from

This image is available from Library and Archives Canada under the reproduction reference number PA-033620 and under the MIKAN ID number 3216646 This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing for more information. Library and Archives Canada does not allow free use of its copyrighted works. See Category:Images from Library and Archives Canada.

Image online from the Library of Parliament [1]

Original title: Robert Poore Haythorne, premier of Prince Edward Island

Photograph by

William James Topley (1845–1930) Description Canadian photographer Date of birth/death 13 February 1845(1845-02-13) 16 November 1930(1930-11-16) Location of birth/death Montreal Vancouver Work location Ottawa, Ontario

, from

This image is available from Library and Archives Canada under the reproduction reference number PA-033620 and under the MIKAN ID number 3216646 This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing for more information. Library and Archives Canada does not allow free use of its copyrighted works. See Category:Images from Library and Archives Canada.

Image online from the Library of Parliament [1]](/bioimages/w600.5323.jpg)

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

HAYTHORNE, ROBERT POORE, farmer, landowner, and politician; b. 2 Dec. 1815 at Mardyke House, Clifton (Bristol), England, son of John Haythorne and Mary Curtis; d. 7 May 1891 in Ottawa.

When 25-year-old Robert Poore Haythorne arrived in Prince Edward Island in October 1841 aboard the Glenburnie, his prospects were bright. He came to join his elder brother Edward Curtis, who had emigrated some years before and had acquired 10,000 acres on the Hillsborough River in Marshfield. The land, which was in part occupied by squatters and partially leased to tenants for 999 years, was still substantially wilderness but had excellent agricultural potential.

The younger Haythorne was no destitute settler. His father, John Haythorne, was a prosperous wool merchant and former mayor of Bristol. Joseph Haythorne, his grandfather, was a banker and glass manufacturer in the same city. Robert had been educated in private schools in Bristol and had then spent several years on a grand tour of Europe, intended to finish his education. His immigration to Prince Edward Island to join his brother was a step in furthering the family fortunes. He came to a colony that was growing rapidly and enjoying general agricultural prosperity. For well-educated, ambitious men of means, it was a time of great promise. The Haythorne brothers soon established a reputation as progressive farmers, respected by both their tenants and their fellow landowners. Edward, for example, was appointed a member of the Legislative Council in 1849. His death in 1859, however, thrust upon Robert alone the problems of household and farm.

After visiting England in 1860, Haythorne returned to Prince Edward Island and on 28 May 1861 married Elizabeth Radcliffe Scott, the eldest daughter of Thomas Scott, an Irishman who had immigrated there in 1812. In 1862 their first son, Edward Curtis, was born and the following year Thomas Joseph arrived. The happiness of this young family was abruptly shattered when Elizabeth died in September 1864 near Liverpool, England, while travelling to visit her family home in Belfast. Haythorne was left with the responsibility for the upbringing of two young children as well as for the management of the Island lands.

Though one of the Island’s leading farmers and landowners, Haythorne took a reformist stance on the land question, which so bedevilled Island politics in the 1860s. By 1866 he had abolished leasehold tenure on his estates and sold land to his tenants and squatters at $2 per acre. His actions won him the support of former tenants and others in the Marshfield area and in 1867 he was elected to the Legislative Council in the 2nd District of Queens County. Haythorne came to public office at a critical period in Island history when politicians faced the difficult issues of confederation, land reform, railway development, and religious controversy. In each of these questions he was to have an important role. His voice, though certainly one of strong conviction on the necessity of resolving the land question and on the dubious benefits of confederation, was consistently one of reason and moderation in the often emotional and bitter sectarian debate.

Within weeks of Haythorne’s election, the conservative government of James Colledge Pope* resigned, to be replaced by a liberal administration headed by George Coles*. Haythorne joined Coles’s cabinet. In 1869, after the resignation of Coles on account of ill health and the appointment of his successor, Joseph Hensley, to the bench, Haythorne found himself premier. He brought to the position a profound scepticism on the issue of confederation, a determination to see the resolution of the land question, and an inclination to view reciprocity with the United States as an attractive option for the Island. When a committee headed by Major-General Benjamin Franklin Butler was sent to Charlottetown in 1868 by the United States Congress, then considering the establishment of free trade with the colony, he saw the mission as having great economic potential for the Island, which had enjoyed unprecedented prosperity during the period of reciprocity from 1854 to 1866.

The interest of Island politicians in a separate reciprocity agreement with the United States helped to pry an offer of “better terms” out of the Canadian government, which along with the imperial authorities had been trying for some time to induce the colony to enter confederation. The Haythorne government nevertheless rejected the new proposal in January 1870 on the grounds that it did not force a resolution of the land question by the British government. In Haythorne’s view, acceptance of the $800,000 offered by the Canadians as a means of buying out the Island’s absentee proprietors would merely compromise the independence of Islanders and of their future representatives in the federal parliament. Perhaps even more significant was the failure of the dominion to assign funds for railway construction in the colony. Haythorne believed that a railway was a critical element in the future development of the Island, but not one that its taxpayers could likely afford. His concern, as it turned out, was prophetic.

The general election of July 1870 returned Haythorne’s liberals with a majority of four votes. The government’s stance on confederation was supported, it seemed, by the electors. Religious controversy, however, was soon the ending of Haythorne’s cabinet. An Anglican himself, Haythorne favoured the grants to Catholic schools that had been requested by Bishop Peter McIntyre, as did two other members of the Executive Council, Andrew Archibald Macdonald* and George William Howlan*. Unfortunately, four of their colleagues, including William Warren Lord*, did not share their views, and the Haythorne administration was forced to resign. The conservative leader, J. C. Pope, managed to assemble a coalition, but only by promising to avoid the schools question for four years.

The Pope government was as convinced of the necessity of a railway as had been Haythorne’s. In 1871 a railway bill was passed and construction began under engineer Collingwood Schreiber* on a line connecting Charlottetown to Alberton in the west and Georgetown in the east. The unbridled enthusiasm of Islanders for the seductive technology of the railway quickly turned to resentment and anger. Charges of over-expenditures, bribery, and influence-peddling led Pope to appeal to the electors in April 1872. The result saw Haythorne back in power, and he was shortly committed to the immediate extension of the railway to the extremities of the Island, to Souris in the east and Tignish in the west. No government, he realized, could ignore this demand and remain in office [see Edward Palmer*]. The desire of Islanders for a railway reaching every significant town in the colony presented the people with an unbearable debt, as both the premier and Lieutenant Governor William Cleaver Francis Robinson had foreseen. Rather reluctantly, Haythorne reopened negotiations with the government of Sir John A. Macdonald in respect to confederation.

Haythorne and his cabinet colleague David Laird* began discussions in February 1873, in Ottawa. By early March terms had been reached, largely through the good offices of Samuel Leonard Tilley. The Canadian government’s offer was generous, and included the taking over of the railway, the assumption of the colonial debt, an $800,000 payment for the acquisition of proprietorial lands, and a promise of continuous steam communication with the mainland. When the provisional terms were agreed upon in Ottawa, the Island legislature was dissolved and an election ensued in April, which saw the conservatives under Pope returned. After minor concessions had been wrung from the dominion, the terms of union were approved and Pope’s government led a somewhat reluctant Island into confederation on 1 July 1873. Haythorne could at least claim co-paternity as a father of confederation.

In recognition of his role, Haythorne was appointed to the Senate and took his new seat in the midst of the uproar over the Pacific Scandal. A senator until his death in 1891, he was a consistent supporter of free trade with the United States and he remained a watch-dog for the interests of the Island in terms of improved communication and transportation. Haythorne retained an interest in his farm at Marshfield, but his two sons chose not to follow their father’s path in agriculture. Thomas emigrated to England, where he practised medicine; he died in 1920 and was buried beside his mother in Liverpool. Edward emigrated to New Zealand and never returned to the Island. In the late 1880s, unable to maintain both the farm and his political career, Haythorne sold his land in Marshfield and purchased a home in Charlottetown. He died, alone, at the Grand Union Hotel in Ottawa in May 1891.

The writers of his obituaries described Haythorne as an “estimable neighbour” and an example of a “reasonable man” who assisted the “struggle for freedom from proprietory bondage.” He would have welcomed these summations of a life.

PAPEI, Acc. 2576. PRO, CO 226. P.E.I., House of Assembly, Debates and proc., 1867–73. Examiner (Charlottetown), 1867–73. Patriot (Charlottetown), 1867–73. Bolger, P.E.I. and confederation. Canada’s smallest prov. (Bolger). W. E. MacKinnon, The life of the party: a history of the Liberal party in Prince Edward Island (Summerside, P.E.I., 1973). I. R. Robertson, “Religion, politics, and education in P.E.I.”

Cite This Article

Andrew Robb, “HAYTHORNE, ROBERT POORE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/haythorne_robert_poore_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/haythorne_robert_poore_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Andrew Robb |

| Title of Article: | HAYTHORNE, ROBERT POORE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |