Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

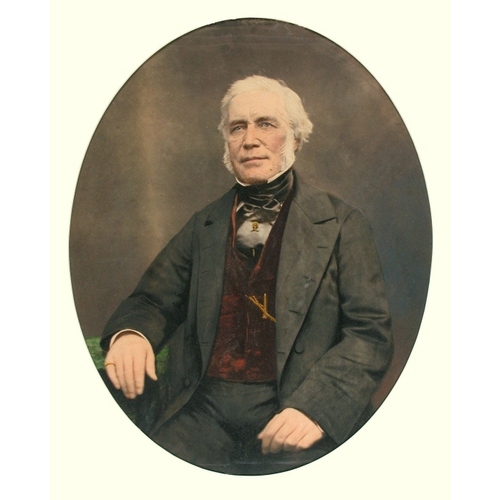

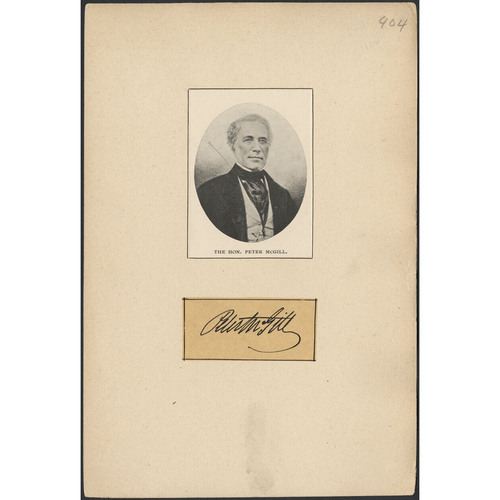

McGILL, PETER (known until 29 March 1821 as Peter McCutcheon), merchant, bank and company director, justice of the peace, and politician; b. August 1789 and baptized 1 September in Creebridge, Scotland, son of John McCutcheon and his second wife, Mary McGill; m. 15 Feb. 1832 Sarah Elizabeth Shuter Wilkins in London, and they had three sons, two of whom survived infancy; d. 28 Sept. 1860 in Montreal.

Peter McGill’s career illustrates the limits to an understanding of the past that is possible through the biographical mode of historical writing. For his importance to the development of capitalism in Montreal has less to do with the man than it does with the many institutions in which he was active. He would owe much of that prominence to inherited wealth and a financially interesting marriage contract. Born to a family of apparently modest means, he arrived in Montreal from Scotland in June 1809, equipped with a grammar school education. His maternal uncle John McGill* was apparently instrumental in finding him a position as a clerk in the Montreal office of the large mercantile firm, Parker, Gerrard, Ogilvy and Company [see Samuel Gerrard]. John McGill had been an officer in the loyalist forces during the War of American Independence. Following the appointment of John Graves Simcoe* as lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, he moved to Niagara where Simcoe, his former commanding officer, appointed him commissary of stores. In a succession of official positions, McGill was active in the public administration and private appropriation that accompanied the establishment of the colony. His wife died in 1819 without leaving him an heir, so he bequeathed his substantial estate to his nephew, provided that McCutcheon adopt his family name. Although the name change became effective by royal licence on 29 March 1821, Peter McGill did not inherit the bulk of the estate until after the death of his uncle in 1834. In all likelihood, however, Peter’s “much beloved uncle” helped him with contributions of capital in his early mercantile partnerships.

The first decade of McCutcheon’s career in Montreal remains obscure. Both his obituaries and the hagiographical biographies published during the 19th century indicate that, after serving his clerkship at Parker, Gerrard, Ogilvy and Company, he was admitted to the firm as a junior partner. He may subsequently have become the junior Montreal partner in Porteous, Hancox, McCutcheon, and Cringan, an importing firm headed by Andrew Porteous* with offices in Montreal and Quebec, but no primary sources have been located to support the claim. In May 1820 McCutcheon entered into a partnership which would be the basis of his mercantile activities for the rest of his business career. The partnership initially consisted of Parker and Yeoward, timber brokers in London; William Price and Company of Quebec; and McCutcheon as the senior partner of a Montreal firm including Kenneth Dowie, known as McCutcheon and Dowie and later as McGill and Dowie. In 1823 there was a major realignment within the partnership. Nathaniel Gould and James Dowie, both of London, replaced Parker and Yeoward as the English partners with a 50 per cent interest in the firm. Kenneth Dowie left the firm and James Hetherington joined the Montreal office, which became Peter McGill and Company. The Montreal and Quebec offices each had a 25 per cent share in the business.

Mercantile partnerships of the early 19th century did not enjoy the legal protection of incorporation. Thus, the firm could be held responsible for claims against its partners for their activities outside the partnership itself, and merchants did frequently engage in business outside their partnerships. The activities of McGill’s partnership were further complicated, for the evidence overwhelmingly suggests that, while the Quebec operations concentrated on the wood trades, the Montreal office was principally an import house.

McCutcheon had been working with Dowie prior to the establishment of the partnership, supplying local merchants and grocers. Between 1820 and 1826, 21 short-term credit arrangements involving either McCutcheon and Dowie or Peter McGill and Company were protested before a Montreal notary for non-payment. In all cases the firm had extended credit either to Montreal area merchants, grocers, and petty commodity producers or to mercantile firms in Upper Canada. The direction of these lines of credit indicates the role of the Montreal firm as a supplier of imported goods rather than an exporter of Canadian produce.

The cargo lists of imports and exports by sea through the St Lawrence valley in 1825 reveal that William Price and Company was a major exporter of wood products, responsible for 36 export consignments and only 6 import consignments in that boom year of the business cycle. The Montreal firm participated only 9 times in export shipments, while being responsible for 14 import consignments.

Peter McGill and Company’s exports included potash, a by-product of land clearance and a staple trade of relatively minor value, controlled by Montreal mercantile firms. McGill’s house was responsible for 1.56 per cent of the total exports of this commodity through the St Lawrence in 1825. The trade, however, was carried on with the English firm of Parker and Yeoward rather than with his partners, Gould and Dowie.

The apparent concentration by Peter McGill and Company on imports of British manufactured goods and on West Indian produce is further revealed by the firm’s relations with its debtors in the years 1825 to 1829. Prior to filing for bankruptcy, a firm could reach agreement with its creditors and assign its assets to trustees, usually chosen from among the leading creditors, to wind up the business. December 1825 saw the first world-wide capitalist crash. Although his firm was not even a creditor of the large import house of Porteous and Nesbitt, the latter’s creditors appointed McGill their trustee in the summer of 1825 to liquidate the assets in the first major assignment in Montreal: a clear indication of McGill’s expertise in the import business. During the crisis years of 1825–29 Peter McGill and Company were involved as creditors in 14 assignments. There the pattern visible in the short-term credit arrangements continued. Grocers and spirit dealers such as Alexander and Lawrence Glass and Alexander Nimmo failed, each owing McGill more than the total value of his firm’s annual potash exports.

The prominence of the import activities of the Montreal firm should not obscure the fact that the firm did have relationships with local commodity producers. In 1827 Peter McGill and Company handled the commercial distribution in the Canadas of over 15,000 gallons of locally produced liquor from the distillery near Courant Sainte-Marie owned by the Handyside brothers. Undoubtedly, some of this produce found its way into the army supply contracts that the firm undertook in that year.

Profiting from a one-quarter interest in William Price*’s growing wood trade and developing an important mercantile business, McGill’s firm invested some of its profits in real estate. The company had been operating out of a leased commercial and residential complex adjacent to the old market in Montreal. This two-storey stone structure was purchased by the firm in 1824, after the first year of an eight year lease. The following year the property was evaluated by Jacques Viger as being worth £5,000.

Profit maximization for mercantile partnerships such as the one linking McGill, Price, Gould, and Dowie could best be achieved by ensuring that at least some of the vessels used in international trade were owned by the firm. McGill’s direct involvement in shipping was limited. Jointly with Price he had the 226-ton brig William Parker built at Montreal in 1820; it was sold two years later in London. The full partnership had seven vessels, including schooners for the coastal trade and barques and brigs for the transatlantic business, built at Quebec, Saint-Jean-Port-Joli, and Sunderland, England, between 1824 and 1837. Most of the vessels were acquired after the world-wide collapse in the price of vessels which followed the crash of 1825. In contrast with Price, who had eight vessels registered in his own name during the same period, McGill never invested in ocean-going vessels on his own account, separate from the partnership, failing to capitalize on his involvement in the sector to build an independant base of wealth.

Thus, the ex officio head of the Montreal business community did not rise to prominence on the basis of staple trades. McGill would become involved in numerous ventures on his own account but few could be considered logical extensions of his activities in the moderately successful firm, described by its letterhead of the mid 1830s as “Importers of British Manufactures, East & West India Produce.”

McGill’s principal business activity outside the partnership was his long association with the Bank of Montreal. He became a member of the board of directors of the bank in 1819 and was elected vice-president in 1830 and president in 1834. For the next 26 years he served as the equivalent to the chairman of the board of the colony’s single most important financial institution. When McGill joined the board, the president was Samuel Gerrard, McGill’s former partner. By the mid 1820s Gerrard had come under increasing attack from within the bank for the manner in which he had managed its affairs. Joint-stock companies were rare in the British empire of the 1820s and, not surprisingly, Gerrard had been running the bank as if it were a mercantile partnership. He had hired personnel and lent the bank’s money in his own name for a number of years. By the time of the crash, loans implicating up to 25 per cent of the bank’s paid-up capital had been lent by Gerrard without any mention that he was lending in his capacity as president. It became evident that the bank would have serious difficulties acting in its own name to recover the outstanding debts. The situation provoked a revolt against the president by several members of the board. Led by George Moffatt* and James Leslie*, these directors tried to force Gerrard’s resignation and to have a new series of rules and regulations drawn up which would ensure that the shareholders would be protected against a similar occurrence in the future.

In every important vote taken on the numerous issues relating to the crisis, McGill supported Gerrard in his struggle against reform. As Gerrard’s protégé, McGill was the only younger member of the board to support the old guard consistently. The Moffatt faction eventually forced Gerrard to resign, but not before McGill managed to block legal actions against him. An industrialist, John Molson* Sr, was brought in as president in June 1826 to put the bank back on the tracks, and in the following year a new cashier (general manager), Benjamin Holmes*, was given enhanced powers but was to report to a committee of the board of directors rather than to the president. Following the premature deaths of Molson Sr’s successors, John Fleming* and Horatio Gates*, McGill acceded to the presidency as the senior member of the board, with 15 years’ experience. The resolution of the crisis provoked by Gerrard had resulted in the stripping of much of the power of the presidency. Ironically, these changes which McGill had fought against permitted him to serve for a longer term than any other president, and thus assured his place in history.

Despite the favourable treatment McGill has received from historians writing about the Bank of Montreal, there is little to suggest that he played a major role in the bank’s continued expansion during his tenure. Indeed, in the key political episode involving its extension into branch banking in Upper Canada, which had been denied by its original charter, the bank obtained the gerrymandering of the Montreal electoral districts in 1841 to ensure that Holmes would be available to guide the necessary legislation through the new Legislative Assembly of the United Province of Canada. This, despite the fact that McGill had already sat on the Executive and Legislative councils before the union of the Canadas and would be reappointed to the Legislative Council in June 1841.

As vice-president of the bank in 1830, McGill had undertaken a trip to Great Britain on behalf of the institution in an attempt to secure a royal charter. The resultant charter was too restrictive to be of much use. While there, McGill married Sarah Elizabeth Shuter Wilkins. Sarah was the daughter of Robert Charles Wilkins, a partner in the important Canadian mercantile firm of Shuter and Wilkins which had been particularly active in the Bay of Quinte region of Upper Canada. She brought to the marriage a dowry of £10,000 in real estate, which was to be placed in a trust fund managed by McGill, with all proceeds accruing to him during their marriage. At his death the trust was to revert to his wife.

McGill reached the height of his career during the early 1830s. The mercantile partnership had survived the crisis years and he had begun to diversify his interests. By 1824 he had become involved in the Marmora ironworks in Upper Canada. Active in the hiring of skilled workmen for this early foundry, he soon limited his relationship with the firm to that of a rentier capitalist. The direct supervision and management was left to Anthony Manahan* and others. In the late 1840s McGill sold the works to Joseph Van Norman*.

On his trip to Great Britain, McGill had negotiated a long-term loan from the estate of George Stanfield to permit Moses Judah Hayes* to purchase and revamp the Montreal waterworks. In cooperation with John Molson Jr and other Bank of Montreal directors, McGill became active in the new steamboat monopoly on the Ottawa River. The Ottawa and Rideau Forwarding Company, a corporate restructuring of the Ottawa Steamboat Company, was to be McGill’s only fruitful long-term investment. At his death in 1860, it was providing him with an annual revenue of £728.

As a member of the Legislative Council since January 1832, the Honourable Peter McGill – for members of council were all honourable men – was active in Lower Canada’s largest land deal. Organized in 1832 by Russell Ellice and Nathaniel Gould, McGill’s London partner, the British American Land Company was sold over a million acres in the Eastern Townships for the sum of £110,321 sterling, by the British government. It thus had a stranglehold on much of the undeveloped agricultural land in the colony. McGill, along with Moffatt, was appointed a commissioner in Canada for the company in 1834. The commissioners’ most important duty, overseeing the purchase of 147 different tracts of land in the developed regions of the townships, was completed by June 1835, thus ensuring almost absolute control over the subsequent agricultural and industrial development of the region.

In 1831 McGill became the first chairman of the board of directors of the Champlain and St Lawrence Railroad, which ran from La Prairie to Saint-Jean (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu). Although he was probably only a minor shareholder in British North America’s first railway (it used wood not only for the ties but for the rails as well), his prominence in the business community had given this early venture greater credibility than it would otherwise probably have merited. In 1845, together with John Alfred Poor*, Alexander Tilloch Galt*, Moffatt, and others, he was an early promoter of the St Lawrence and Atlantic Rail-road. He sat on the first board of directors of the railway which, when completed, would link Montreal and Portland through the Eastern Townships. Upon the railway’s merger with the Grand Trunk in 1853, he went on to the new board.

McGill was not only an honourable man, but a religious man. A life-long member of the Church of Scotland, he and John Redpath* owned St Paul’s Church in Montreal and only sold it to the trustees on condition that it and its associated school be kept free of the heresies of the “Great Disruption” or the Erskinites. Lest it be thought that this defence of Calvinist orthodoxy by McGill was evidence of a narrow-minded approach to religious matters, it should be stressed that Sarah, who was a member of the Church of England, brought up their sons, John Shuter Davenport and Sydenham Clitherow, as Anglicans, and McGill subsidized the construction of the Congregational church. It must be admitted that the latter was part of a larger real estate deal in which McGill was attempting to develop a number of lots, and the church would serve as a selling point. Be that as it may, he was a long-time president of the Montreal Auxiliary Bible Society (1834–43) and the Lay Association of Montreal (1845–60) and was elected elder of St Paul’s in 1845.

McGill was also a community leader in matters social and mystical. The first president of the St Andrew’s Society (1835–42), he went on to become the provincial grand superintendent of Royal Arch masonry for the Province of Canada. While holding that post from 1847 to 1850, he also served the almost mandatory term of president of the Montreal Board of Trade in 1848.

McGill had been a member of the Legislative Council from January 1832 to March 1838. In April 1838 he was appointed to the Special Council set up with dictatorial powers following the rebellion of 1837. He sat for two months and from November 1838 to 1841 was a member of both the Special and Executive councils. As president of the Constitutional Association of Montreal from 1836 to 1839, McGill had been the spokesman for the Anglo-Scottish mercantile community and he had advocated the union of Upper and Lower Canada as a solution to the colonies’ problems. After the union in 1841, he was again appointed to the Legislative Council and remained a member until his death, serving as its speaker from May 1847 to March 1848. Concomitant with his term as speaker, he again served on the Executive Council, as a member of the conservative ministry of Henry Sherwood and Denis-Benjamin Papineau until December 1847 and, after Papineau’s resignation, in the ministry led by Sherwood alone. A justice of the peace for the district of Montreal since at least 1827, McGill had participated in the day to day running of the city in the years prior to its gaining a charter. He was therefore a politically safe person for the Colonial Office to appoint as the city’s first mayor in 1840. He declined to seek elective office when the first mayoralty campaign took place in 1842. Thus, although McGill held high political office, it was always as an appointed official, a fact that bears witness more to the importance of his business connections and those of the Bank of Montreal than to any particularly strong political character of the man himself.

McGill had gone heavily in debt to his partners as the result of a speculative mercantile venture in 1843. As late as 1859 he owed £40,981 in principal plus 16 years’ back interest to his London partners. The situation was further complicated by his debt to the firm as a result of the £70,000 sterling that Price owed the London partnership, dating from 1853. McGill had acted as surety for Price’s loan from the partnership. For the last 17 years of McGill’s life, his business was in liquidation. It was only by mortgaging his wife’s trust fund that he was able to borrow £30,000 from the Bank of Montreal in 1859. By borrowing from a bank of which he was president and by using his wife’s dowry, McGill was able to reschedule his heavy debt load.

McGill’s active career in a variety of fields necessarily leads to a distorted perception of its nature. But if the same criteria of profit and loss which are used to judge the success of a firm’s operations are applied to the career of an individual mercantile capitalist, McGill was clearly a failure. After all outstanding debts had been settled, the estate McGill left to his two sons was a very modest one: each received only $36,174. The ex officio head of the Montreal business community failed to establish a fortune that would ensure the continuance of the McGills as a leading bourgeois family in the city. The reality behind the public image was an estate comparable to one a minor industrialist might have accumulated. Perhaps this explains his request that the funeral arrangements be of a “plain inexpensive and unostentatious manner.” Yet, conscious of image to the end, McGill had asked to be buried in Mount Royal Cemetery in the presence of his domestic servants, all sporting mourning suits provided by the estate. The estate also paid for the publication of the sermon preached in his honour on the Sunday after his death.

McGill’s failure is understandable when placed within the context of the profound changes in the organization of the Montreal economy. His career coincided with the industrial revolution and in a period when the leading bourgeois families of the city would increasingly owe their wealth to the control of the means of production, McGill, despite numerous opportunities in manufacturing and transportation, failed to take advantage of his situation. Unlike his colleagues Molson and Redpath, he remained essentially a mercantile capitalist in the new age of industrial capitalism.

[In the absence of the records of Peter McGill and Company, the history of the firm must be reconstituted from the following materials: ANQ-M (CN1-295, 7 oct., 30 déc. 1826; 10 mars, 7 juin 1827); Montreal Business Hist. Project (Assignment cross-reference file; General agreement file; Monetary protests, nominal series); Quebec Commercial List (Quebec), 1825; and Joanne Burgess and Margaret Heap, “Les marchands montréalais dans le commerce d’exportation du Bas-Canada, 1815–1888” (paper delivered before the Institut d’histoire de l’Amérique française, Montreal, in 1978). r.s.]

ANQ-M, CM 1, 1/17; CN1-7, 22 mars 1833; CN1-187, 8 sept. 1823, 22 févr. 1827, 16 janv. 1844; CN1-102, 2 févr.–17 juin 1835; CN1-134, 6 nov. 1824, 12 juin 1826, 11 oct. 1828; P1000-3-309. ASQ, Fonds Viger–Verreau, carton 46, liasse 9. McGill Univ. Libraries (Montreal), Dept. of Rare Books and Special Coll., ms coll., CH297.S257; CH377.S337; CH341.S301; CH423.OLS; CH441.RBR. PAC, MG 28, II2; RG 68, General index, 1651–1841, 1841–67. William Snodgrass, The night of death; a sermon, preached on the 7th Oct., 1860, being the first Sabbath after the funeral of the Honourable Peter M’Gill (Montreal, 1860). Globe, 3 Oct. 1860. Montreal Gazette, 28 Feb. 1828, 21 Feb. 1835, 1 Oct. 1860. William Notman and [J.] F. Taylor, Portraits of British Americans, with biographical sketches (3v., Montreal, 1865–68). Terrill, Chronology of Montreal. Denison, Canada’s first bank. Albert Faucher, “La condition nord-américaine des provinces britanniques et l’impérialisme économique du régime Durham–Sydenham, 1839–1841,” Histoire économique et unité canadienne (Montréal, 1970). Tulchinsky, River barons. Adam Shortt, “Founders of Canadian banking: the Hon. Peter McGill, banker, merchant and civic leader,” Canadian Bankers’ Assoc., Journal (Toronto), 31 (1923–24): 297–307.

Cite This Article

Robert Sweeny, “McGILL, PETER (Peter McCutcheon),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 9, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcgill_peter_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcgill_peter_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert Sweeny |

| Title of Article: | McGILL, PETER (Peter McCutcheon) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | April 9, 2025 |