Source: Link

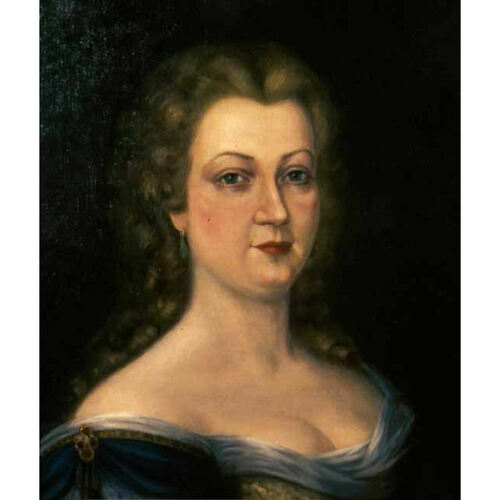

RAMEZAY, LOUISE DE, seigneur; b. 6 July 1705 at Montreal, daughter of Claude de Ramezay*, governor of Montreal, and Marie Charlotte Denys de La Ronde; d. 22 Oct. 1776 at Chambly (Que.).

Louise de Ramezay received her schooling at the Ursuline convent in Quebec. Having remained single like her sister Marie-Charlotte*, dite de Saint-Claude de la Croix, she was led when she was about 30 to take an interest in the administration of part of her family’s properties. In particular she was concerned with the sawmill that her father had built early in the century on the banks of the Rivière des Hurons, in the seigneury of Chambly not far from his own seigneury of Monnoir. Shortly after his death in 1724, his widow had gone into partnership with Clément de Sabrevois de Bleury to run the sawmill. From 1732 until 1737, however, a protracted lawsuit, which Louise de Ramezay followed closely, set the two former partners against each other. Mlle de Ramezay probably acquired at that period the knowledge necessary for running the mill, as well as the other enterprises of which she later became the owner.

For more than three decades beginning in 1739, Louise de Ramezay faithfully saw to it that the sawmill on the Rivière des Hurons was not idle, for every year the operation had to pay 112 livres in rent to the seigneurs of Chambly and 600 livres to her sisters and her brother Jean-Baptiste-Nicolas-Roch, who were also heirs to their father’s estate. The mill was well situated to saw the wood from the upper Richelieu and Lake Champlain and thus to supply timbers, planks, and sheathing to the shipyards at Quebec. Louise de Ramezay did not always run the enterprise in person. At certain periods she supervised production closely, collaborating with the foreman and going to Quebec to sell the lumber; at others, having leased the sawmill and even the right to grant land and collect the rents in the seigneury of Monnoir, she was primarily concerned with getting her share of the revenue. When she entrusted the mill to a foreman, she preferred him to know how to keep the accounts; to one who was illiterate, she gave permission in his contract “to take an hour every day to learn to read and write, and to have himself taught by one of the men hired at the mill who would take the same time to teach him.” Such a clause was quite uncommon, but it gave her the hope that the foreman would eventually keep the accounts well.

Contracts for taking charge of the sawmill were made in succession at about five-year intervals until 1765, proof of success and of virtually uninterrupted operation. During her years of management, however, Louise de Ramezay had to deal with a number of problems. On the two occasions when she farmed out the sawmill she had difficulty getting the conditions of the lease carried out. First, in 1756, a lumber merchant from Chambly, François Bouthier, owed her more than 12,000 livres for two years of rent and goods advanced much earlier. In 1765 she again tried the experiment with Louis Boucher de Niverville de Montisambert, but at the end of a few years, as accounts were not yet settled, legal action was initiated. She no doubt was afraid at one point of finding herself dragged into a prolonged lawsuit, as her mother had been 40 years earlier. She soon agreed with Montisambert that to avoid the delays and expense of a court case it was better to have the dispute settled by the parish priest of Chambly, Médard Petrimoulx. In August 1771 the priest decided in her favour and concluded that Montisambert had to pay her 3,284 livres.

Louise de Ramezay was also interested in two other sawmills; these are known, however, only through documents that show her as intending to put mills into operation, in particular deeds of partnership and building transactions. In 1745 she entered into partnership with Marie-Anne Legras, the wife of Jean-Baptiste-François Hertel de Rouville, and the two entrepreneurs had a sawmill and a flour-mill built “on the seigneury of Rouville, on the stream called Notre-Dame de Bonsecours, on a piece of land belonging to the . . . Sieur de Rouville.” These two mills doubtless turned a satisfactory profit, since the partnership lasted 16 years; it was not dissolved until 1761, six years before the anticipated date. The second sawmill was to be located much farther south, in the seigneury of La Livaudière, west of Lake Champlain. This seigneury, which had initially been granted to Jacques-Hugues Péan* de Livaudière, had been withdrawn in 1741 and returned to the king’s domain. When the seigneury had belonged to him, however, Nan had granted land to a habitant from Saint-Antoine-sur-Richelieu, Jean Chartier, with the authorization “to take sawn timber on the whole of the aforementioned seigneury where the lands had not been given in grants.” Moreover, a stream that crossed Chartier’s land and flowed into Lake Champlain by way of the Chazy River (probably the Great Chazy River. N.Y.) could supply the power needed for running a mill. It was probably this set of favourable circumstances that prompted Louise de Ramezay to go into partnership with Chartier in August 1746 and to have a sawmill built at once on his land, near the Chazy River. Moreover, in 1749 she obtained a grant from the colonial authorities of a domain on Lake Champlain, the seigneury of Ramezay-La-Gesse, which extended on both sides of the Rivière aux Sables (probably the Ausable River, N.Y.). Although a sawmill does not seem to have been built there, the interest of this property obviously lay in its abundant timber reserves.

Louise de Ramezay did not confine her activities to the lumber industry. In 1749 she bought from Charles Plessy, dit Bélair, the tannery that had belonged to his father Jean-Louis* and was located in Coteau-Saint-Louis on Montreal Island. In 1753 she went into partnership with a master tanner, Pierre Robereau, dit Duplessis, to whom she entrusted the operation of the tannery. Until she was 60, she appears to have lived mainly in Montreal, often going to Chambly and Quebec.

It is not possible with the available documentation to evaluate precisely the extent of Louise de Ramezay’s economic activity. In the transactions related to the lumber or leather industries, however, she always seemed able to advance the money necessary for construction work, for fitting-out or repairs, for the foremen’s and workmen’s wages, for the purchase of land, equipment, and goods, or for repayment of debts contracted by a partner or employee. These are additional signs of the efficiency and success of her enterprises. She owed this success in part to her own administrative abilities, but probably even more to her social position: the descendant of a great family, the daughter of a governor, the “very noble young lady,” as the documents of the period call her, enjoyed privileges that were by no means negligible. Besides an upbringing that had prepared her for the realities of her situation, her relations within the colonial aristocracy certainly on more than one occasion brought her useful advice, information, recommendations, and even a few favours in connection with the lumber industry, the exploitation of timber limits, the purchase of domains, or her own financial resources. For example, after her mother’s death in 1742 she was the beneficiary of an annual and comfortable pension of 1,000 litres, because the authorities in France had decided to extend the pension paid to Mme de Ramezay as the widow of a former governor of Montreal. In addition, in 1746 Bishop Dosquet gave her half of the seigneury of Bourchemin, an enclave within the seigneury of Ramezay, which she demanded in the name of her family’s claims on that domain: the bishop on this occasion wrote to her: “I am delighted to have this small opportunity to give proof of my attachment to your family.” Thus Louise de Ramezay owned, in her own right, half of the seigneury of Bourchemin as well as the seigneury of Ramezay-La-Gesse; in addition, in 1724, along with her brothers and sisters she had inherited from her father the seigneuries of Ramezay, Monnoir, and Sorel. When all is said and done, her economic activities could rest on the kind of substantial landed fortune of which there were but few examples in the colony in the mid 18th century.

With the conquest and the establishment of the southern border of Canada, Louise de Ramezay lost her seigneury of Ramezay-La-Gesse, and also, if indeed it still belonged to her, the mill near the Chazy River. At the same period she parted with other properties. In 1761 she sold her rights to the seigneury of Sorel to her sister Louise-Geneviève, the widow of Henri-Louis Deschamps* de Boishébert, for 3,580 livres. Three years later this property was sold to a Quebec merchant, John Taylor Bondfield, as was the seigneury of Ramezay on the Yamaska River, in which Louise had kept her share. In 1774, two years before her death, she also sold her half of Bourchemin. Monnoir apparently remained in the family until the end of the century; towards the end of her life she made grants of a considerable number of lots there at the request of habitants in the Richelieu valley.

Louise de Ramezay, unmarried and a member of the aristocracy, administered the properties for which she was responsible conscientiously and with remarkable constancy, at the same time drawing the greatest possible advantage from the privileges of her class.

[The printed sources dealing with Louise de Ramezay’s economic activities have circulated certain inaccuracies, based, it seems, on a somewhat free interpretation of archival sources. Thus, following Ovide-Michel-Hengard Lapalice, Histoire de la seigneurie Massue et de la paroisse de Saint-Aimé (s.l., 1930), 34, various authors have wrongly located the sawmill of the Rivière des Hurons, and even that of the Ruisseau Notre-Dame de Bonsecours, placing them in the seigneury of Monnoir. Édouard-Zotique Massicotte*, “Les Sabrevois, Sabrevois de Sermonville et Sabrevois de Bleury,” BRH, XXXI (1925), 79–80, gives Mlle de Ramezay “a couple” of tanner’s shops, when the documents indicate only one; moreover, Lapalice states inaccurately that “in 1735 Lousie de Ramezay moved all the working stock of the tannery to Chambly.” With regard to the debts owed to Mlle de Ramezay by various persons in 1751 and 1756, Massicotte, “Une femme d’affaires du Régime français,” BRH. XXXVII (1931), 530, multiplies by five the sums indicated in the documents (did he intend to convert to dollars and then neglect to say so?); as a result, several authors have overvalued the importance of Louise de Ramezay’s transactions. Finally, the title of “businesswoman” that Lapalice and Massicotte give Mlle de Ramezay is totally anachronistic in reference to this 18th-century noblewoman. It should be noted that the passages relating to Louise de Ramezay in the biography of her father (DCB, II, 548) repeat some of these inaccuracies. h.p.]

ANQ-M, Fiat civil, Catholiques, Saint-Joseph (Chambly), 1776; Greffe d’Antoine Grisé, 6 août 1765, 8, 26 juill.1768, 1er, 15 juill. 1769, 16 nov. 1770, 23 mai, 16, 30 août 1771, 24 oct. 1772, 25 août 1774; Greffe de Gervais Hodiesne, 14, 17 juin, 20 déc. 1745, 18 mars, 19 avril, 30 juin, 29 août 1746, 1er févr. 1749, 19 sept. 1751, 16, 30 avril 1753, 6 juill., 6 sept. 1754, 26 sept. 1756. 8 oct. 1758, 17 mars 1760, 5 mai, 1er déc. 1761: Greffe d’Antoine Loiseau, 2 sept. 1739; Greffe de François Simonnet, 26 mars 1746. Archives paroissiales, Notre-Dame (Montreal ), Registre des baptêmes, mariages et sépultures, 1705. P.-G. Roy, Inv. concessions, II, IV, V. J.-N. Fauteux, Essai sur l’industrie, I, 204–10. Mathieu, La construction navale, 75–76, 87–90.

Cite This Article

Hélène Paré, “RAMEZAY, LOUISE DE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 21, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ramezay_louise_de_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ramezay_louise_de_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hélène Paré |

| Title of Article: | RAMEZAY, LOUISE DE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1979 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | December 21, 2024 |