Source: Link

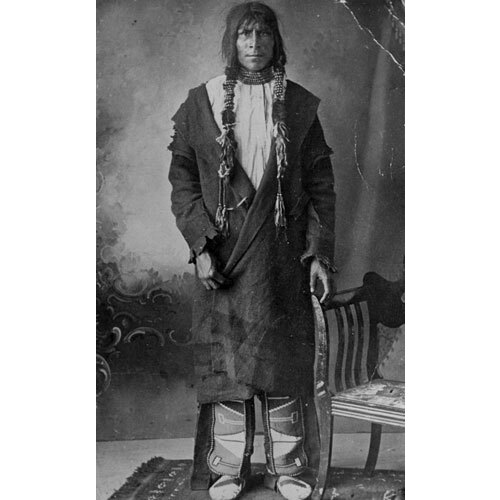

KITCHI-MANITO-WAYA (Kakee-manitou-waya, Kamantowiwew, Almighty Voice, also known as Jean Baptiste), Indian hunter and fugitive; b. c. 1875 probably near Duck Lake (Sask.), son of Plains Saulteaux Indian Sinnookeesick (Sounding Sky) and Natchookoneck (Spotted Calf, Calf of Many Colours), daughter of Willow Cree chief One Arrow [Kāpeyakwāskonam*]; he had four wives and one child; d. 30 May 1897 in the Minichinas Hills near Batoche (Sask.).

As he grew up on the One Arrow Indian Reserve (Sask.), Almighty Voice heard the stories of his grandfather One Arrow, who had resisted settlement on the reserve until 1879; of his father, who had participated in the North-West rebellion of 1885 [see Pītikwahanapīwiyin*]; and of other band elders. These tales of battle, raids, and the hunt contrasted markedly with the Plains Cree way of life in the mid 1890s, when they saw their territory controlled by whites, invaded by enemy tribes, and infringed upon by mixed-bloods. Placed within the humiliating confines of the reservations, they could only travel with a pass and hunt within limitations. In their youth Almighty Voice’s grandfather and father had ridden into great herds of buffalo to kill their meat; now there were only government steers distributed among the mendicant Crees on their reserves by the agents of the dominion government.

Countless victories in running competitions at Prince Albert (Sask.) and a well-deserved reputation as a superb marksman and splendid hunter failed to sate Almighty Voice’s hunger for distinction or inure him to the ways of the white man. On 22 Oct. 1895 North-West Mounted Police sergeant Colin C. Colebrook arrested him for having killed a government steer and escorted him to the prison at Duck Lake. It may have been comments made jokingly by one of his guards that the penalty for such a crime was hanging, the most ignoble end imaginable for an Indian, that caused Almighty Voice to react. Whatever the reason, he made his escape that same night. He slipped through the window of the guardhouse, ran 6 miles to the South Saskatchewan River, swam the icy waters, and ran another 14 miles to the temporary safety of his mother’s lodge on the reserve. The initial attempts by the NWMP to recapture him were ineffectual, and not until he left the reserve a few days later was his trail picked up by Colebrook and a Métis tracker. They came upon him near Kinistino (Sask.) on 29 October and Colebrook approached to make the arrest. Almighty Voice warned that he would shoot. When the sergeant continued to close in, Almighty Voice levelled his double-barrelled muzzle-loader and shot Colebrook through the heart. The man-hunt was immediately intensified but Almighty Voice thwarted the best efforts of the NWMP and remained at large for the next 19 months.

In the mid 1890s the NWMP and the white inhabitants of the North-West Territories had every reason to fear another uprising similar to the rebellion of 1885. Indians had already been demonstrating for a few years a distinct aversion to submission and on several occasions police authority had been defied. Following the killing of Sergeant Colebrook, there were other incidents of Indians firing upon the NWMP, such as the one involving Blackfoot Indian Charcoal [Si’k-okskitsis], who shot and killed a NWMP sergeant in order to avoid capture. In February 1896 the Prince Albert Advocate, commenting on the Almighty Voice case, reported that the Indians were in a defiant mood. “They are now openly boasting that an Indian can shoot a white man and nothing is done or said by the government to bring him to justice. They are just awaiting the advent of spring and clear ground to sally forth and avenge supposed wrongs.” By May 1897 Commissioner Lawrence William Herchmer*, head of the NWMP, was seeking reinforcements from the Department of Indian Affairs and expressed his concern about “‘the almighty voice’ trouble developing into a general rising.”

These were undoubtedly months of great excitement for Almighty Voice. He was now a real Indian, a warrior in the tradition of his forefathers, and for some of his own people he was a hero. Immediately after the murder of Colebrook, the NWMP took his father, Sounding Sky, into custody to prevent him from assisting Almighty Voice. On 20 April 1896 Secretary of State Sir Charles Tupper* issued a proclamation offering a $500 reward for information leading to the apprehension and conviction of Almighty Voice. He was described as a young man of about 22 years of age, 5´10” in height, of fair complexion, “slightly built and erect” with “neat small feet and hands, . . . wavey dark hair to shoulders, large dark eyes, broad forehead, sharp features and parrot nose with flat tip, scar on left cheek running from mouth towards ear, feminine appearance.” Regardless of the efforts made to apprehend him, the fugitive, assisted by his people and sheltered by the broken, wooded country of the area, successfully eluded all attempts to capture him. Telegraph and newspaper reports had him at points hundreds of miles apart on the same date. On 19 June 1896 the Edmonton Herald reprinted a report from an American newspaper falsely announcing that he had been captured several hundred miles southwest of the One Arrow reserve, in Kalispell, Mont.

Almighty Voice had contended that the steer he had killed had belonged to his father, not the government, and by January 1896 this contention received some official substantiation. Inspector John B. Allan, one of the officers involved in the man-hunt, reported that “the feeling is gaining ground among the French Half-breeds and others to the effect that ‘Almighty Voice’ was originally arrested on the report of a child . . . and that he had committed no crime in the first instance.” Herchmer commented that there appeared to be no evidence against Almighty Voice on the original charge and that they would have had to release him the morning after his arrest if he had not escaped. The turn of events, however, had carried the case far beyond the original mistaken charge and Almighty Voice was now a “bad Indian” to be tracked down.

After a year and a half of following up rumours and false leads, the NWMP obtained an accurate report: Almighty Voice and two companions had shot and wounded a local Métis scout near Duck Lake on 27 May 1897. Inspector Allan set out the next day from Duck Lake with a patrol of a dozen men, and found the three Indians in the Minichinas Hills, only a few miles southeast of the One Arrow reserve. They had dug a deep pit in the thickest part of a poplar bluff and from this cover they fired on the police, seriously wounding Allan and a sergeant. Civilians from the area were called upon as special constables to reinforce the NWMP and later in the day a small force unsuccessfully tried to take the Indians by storm. The postmaster at Duck Lake and a constable were killed in the attempt and a corporal was mortally wounded. Reinforcements, including a group of civilian volunteers from Prince Albert, with a seven-pound brass field gun, arrived shortly afterward and surrounded Almighty Voice’s position.

The following day Assistant Commissioner John Henry McIllree was dispatched to the scene from Regina with Inspector Archibald Cameron Macdonell, 24 men, a nine-pound field gun, and an artillery team. They reached the site that evening and during the night action was limited to some sporadic exchange of gunshot and a few rounds from the seven-pound gun. The next morning, while Almighty Voice’s mother sat on a nearby hill singing her son’s war song and hundreds of local residents looked on, the NWMP bombarded the grove. After no sound was heard from the three Indians, the police rushed the bluff where they found the bodies of Almighty Voice, his brother-in-law Topean, and his cousin Little Saulteaux.

The Almighty Voice incident had been cause for real concern both for the Canadian government and the NWMP. Commenting on the killing of Sergeant Colebrook in his annual report for 1895, Commissioner Herchmer had noted, “While the larger proportion of the Indians mean well towards the whites, excitement, or the natural cussedness of a few young Indians may at any moment precipitate serious trouble.” In addition to what Herchmer chose to call “natural cussedness,” the economic circumstances of the Indians on the reserves during this period undoubtedly prompted some of the rebelliousness. Hunting and fishing were poor. The Indians pointed out that the daily treaty ration provided by the government was inadequate and that it was difficult to earn money by working for whites or selling them wood. The severe winter of 1896–97 caused heavy losses of cattle, especially oxen used for freighting and hauling wood. As Superintendent John Cotton of Battleford (Sask.) pointed out in his report for 1897, “A hungry Indian like a hungry white man is not as docile or as contented as he is found to be under more favourable circumstances.” The tragedy of Almighty Voice and the Indians of the North-West Territories in the 1890s was perhaps best underlined by the Toronto Evening Telegram: “Almighty Voice was the champion of a race that is ‘up against it’ in civilization. The wonder is, not that an occasional brave cuts loose, but that all the braves do not prefer the sudden death to the slow extinction of their people.”

NA, MG 29, E69; RG 10, 133, 8618; RG 18, A1, 137–38; B1, 1347, 1398; B5, 2480. Univ. of Sask. Library (Saskatoon), Morton ms coll .,

Cite This Article

S. D. Hanson, “KITCHI-MANITO-WAYA (Kakee-manitou-waya, Kamantowiwew) (Almighty Voice, Jean Baptiste),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kitchi_manito_waya_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kitchi_manito_waya_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | S. D. Hanson |

| Title of Article: | KITCHI-MANITO-WAYA (Kakee-manitou-waya, Kamantowiwew) (Almighty Voice, Jean Baptiste) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |