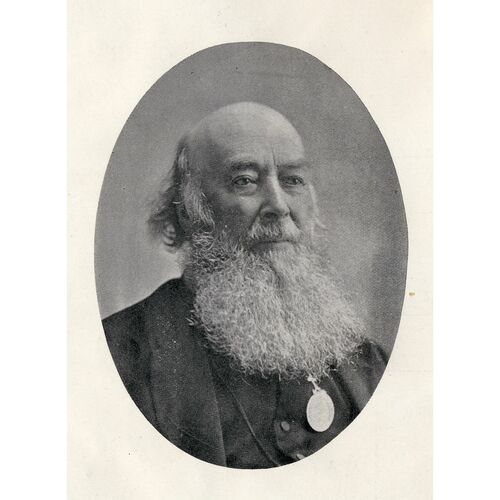

CHINIQUY, CHARLES (baptized Charles-Paschal-Télesphore), Roman Catholic priest, Presbyterian minister, and author; b. 30 July 1809 in Kamouraska, Lower Canada, son of Charles Cheniquy, a law student, and Marie-Reine Perrault; m. 26 Jan. 1864 Euphémie Allard, and they had three children; d. 16 Jan. 1899 in Montreal.

In 1818 Charles Chiniquy, whose parents were living at La Malbaie, went to finish his primary schooling in the parish of Saint-Thomas (Montmagny). He was 12 when his father, who was reputed to drink to excess, died suddenly. His uncle, Amable Dionne*, took him into his home in Kamouraska and in 1822 sent him to study at the Séminaire de Nicolet. He proved to be an “excellent pupil,” gifted in public speaking and praised for his piety. In 1829 he took the first steps leading to the priesthood, and four years later he was ordained priest by Bishop Joseph Signay* in Notre-Dame cathedral at Quebec.

A short time later Chiniquy was named assistant priest at Saint-Charles, near Quebec. In May 1834 he was at Charlesbourg and in September in the parish of Saint-Roch at Quebec. He also served as chaplain at the Marine and Emigrant Hospital, where he met Dr James Douglas*. The physician instructed him about the ravages of alcohol and steered him into the struggle for temperance. Chiniquy’s fondness for flamboyant gestures, his craving to please, his tendency to parade his virtues and to flatter those in authority, all irritated his colleagues and disturbed his superiors. Some considered him a schemer.

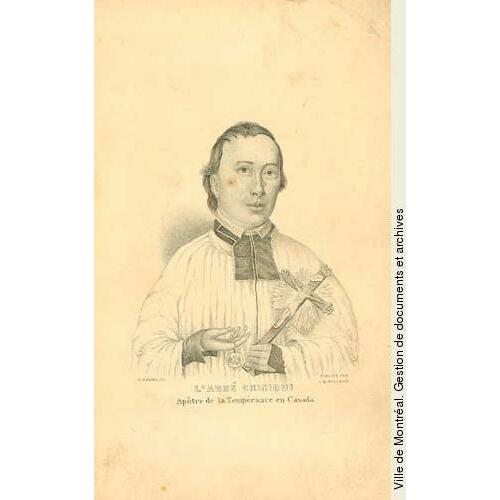

Nevertheless Signay, now archbishop of Quebec, named Chiniquy on 21 Sept. 1838 curé of La Nativité-de-Notre-Dame in Beauport, one of the largest and most prosperous parishes in the Quebec region. Alcoholism was rampant in the parish and absorbed all Chiniquy’s energies, since he had found his vocation in fighting against the ravages of alcohol. He was neither the first nor the only person in Lower Canada to engage in this struggle, but he was certainly the most dynamic element in the original team, which included Patrick Phelan*, Édouard Quertier*, and Alexis Mailloux*. On 29 March 1840 Chiniquy founded a temperance society, which 1,300 parishioners joined, promising to avoid intemperance, to refrain from strong drink, and to stay away from taverns. When in 1841 Chiniquy went further and proposed total abstinence, 812 parishioners signed up and wore temperance medals.

Chiniquy went around the parishes near by, and preached in Notre-Dame church at Montreal on 24 Oct. 1841 and Notre-Dame cathedral at Quebec on 24 June 1842. His fame spread. The erection of a temperance column at Beauport, which French preacher Charles-Auguste-Marie-Joseph de Forbin-Janson* came to bless in September 1841 in the presence of a crowd of about 10,000 people, was a veritable triumph. Chiniquy, like Forbin-Janson, used spectacular preaching methods. Drawing upon an abundant repertory of tragic examples, he sought to impress and frighten. In his sermons he described, with a wealth of detail that sometimes verged on the vulgar, the corrosive effects of alcoholism on the human body, as well as its consequences for the individual and his family; in the midst of sobs and cries of joy he would invite parishioners to come forward to the altar, repent, and sign their temperance pledge. This preaching produced a genuine religious transformation in Beauport.

On 28 Sept. 1842 Chiniquy became assistant to Jacques Varin, the parish priest of Saint-Louis at Kamouraska. Archbishop Signay may have been trying to bring him back to the path of humility or to provide help for Varin, who was ill. He may have heard something of the misadventure said to have occurred between Chiniquy and the housekeeper at the presbytery in Beauport. The infuriated Chiniquy remonstrated against the decision with Signay’s secretary and organized protests by a group of Beauport ladies, but ultimately he had to give in.

When Varin died on 11 April 1843, Chiniquy replaced him, officially becoming parish priest. He tackled his work enthusiastically, attended to the schools, and preached temperance in and around his parish. The publication at Quebec in April 1844 of a book he dedicated to Canadian youth, Manuel ou règlement de la société de tempérance, which had a print run of 4,000, made him the official theorist of total abstinence and thrust him into the foreground. Admired and adulated, Chiniquy was indefatigable; he preached without respite.

In October 1846 Chiniquy announced that he was entering the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. He told his parishioners that he felt called by God to follow this path. Later he would justify his decision by stressing that he could not promote temperance throughout the land if he remained parish priest at Kamouraska; the Oblates, a congregation dedicated to preaching, could provide him with an army of preachers. He arrived at the noviciate in Longueuil having delivered sermons on temperance to cheers and acclaim all along the way. The truth, however, proved less flattering: Chiniquy was admitted by the Oblates at the request of the archbishop of Quebec to atone there for a transgression. While preaching a retreat at Saint-Pascal he had pressed his attentions upon a housekeeper and had been caught in the act.

Chiniquy did not adapt well to the rule of the community. Obedience, utter submission, and solitude weighed upon him. His active nature swiftly reasserted itself: he was critical, anxious to reform everything. In particular, he sent a memorandum to the superior general of the Oblates, Bishop Charles-Joseph-Eugène de Mazenod, deploring the appointment of Joseph-Bruno Guigues* to the episcopal see of Bytown (Ottawa). He had gone too far. He was turned out. In October 1847 he withdrew to the home of his friend Louis-Moïse Brassard*, the curé of Longueuil, where he stayed until October 1851.

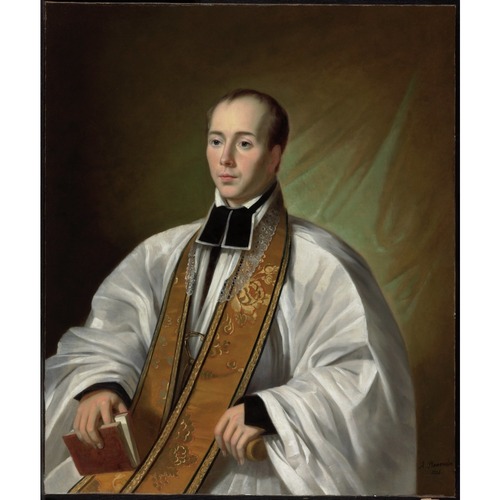

In January 1848, doubtless thinking that his punishment had lasted long enough, Chiniquy asked Archbishop Signay for permission to resume duties in the archdiocese of Quebec. He met with a curt rebuff. However, the bishop of Montreal, Ignace Bourget*, entrusted him with preaching temperance in his diocese. His crusade began in 1848 and ended in the autumn of 1851. The Mélanges religieux of 10 Aug. 1849 asserted that in 18 months Chiniquy had delivered more than 500 sermons and inspired 200,000 conversions to temperance. On many occasions he received magnificent tokens of grateful appreciation: Bourget gave him a gold crucifix that he had brought back from Rome; in 1848 the parishioners of Longueuil with great pomp and ceremony presented him with a portrait of himself by Théophile Hamel*; in 1849, before a crowd of 9,000 people at Longueuil, he received a gold medal. He was dubbed the apostle of temperance.

Yet, though he was at the height of his popularity, Chiniquy felt that he was going round in circles. Seeking new challenges, he tackled L’Avenir, a radical newspaper, and in strongly worded exchanges he defended the church, the papacy, and the clergy’s right to intervene in public affairs, condemned annexation to the United States, and examined the question of emigration to that country. At Pointe-aux-Trembles (Montreal) he crossed swords with the French Protestants (who were called the Swiss).

Bishop Bourget was deeply grateful to Chiniquy. With considerable affection, he advised him to show moderation in his preaching, avoid flattering those in power, shun trivialities, vulgar language, or personal remarks, and be on his guard against vanity. He also suggested that he restrict his activities. It was consequently with great sadness that in the autumn of 1851 Bourget asked him to leave his diocese for the same reasons that had occasioned his departure from Beauport and Kamouraska.

Circumstances let Chiniquy leave head held high. In October 1851 the bishop of Chicago, James Oliver Van de Velde, was visiting in Montreal, and Chiniquy offered him his services. Bourget facilitated the process by getting his exeat from Archbishop Pierre-Flavien Turgeon* of Quebec. In this way Bourget was able to settle a difficult matter, while offering Chiniquy the opportunity for a fresh start. Chiniquy was familiar with the problems of the Canadians who had emigrated to the United States, since his temperance crusade had taken him among them. Elated and impassioned, he already saw himself invested with responsibility for a great mission: directing all these French-speaking Catholics. Lower Canadian leaders feared, however, that Chiniquy’s popularity and his enthusiasm for singing the praises of Illinois would accelerate the exodus, contribute to the depopulation of the countryside, and divert settlers from the townships.

Chiniquy settled at St Anne, Ill. It was his dynamism and charisma, as well as the construction of the Illinois Central Railroad at Kankakee, that helped St Anne to develop much faster than the surrounding communities. Chiniquy’s parishioners, only too happy to re-create under his direction a corner of the lost motherland, were generous in their giving, and soon a church, presbytery, and boys’ school were built. In March 1856, noting that he lived among 10,000 Canadians who had settled in the shadow of the crosses he had raised, Chiniquy asked for some French Canadian priests to be sent him, emphasizing that the Irish bishops could not be counted on to assure the salvation of the emigrants. His colleagues in the surrounding parishes, inconspicuous and less dynamic, were envious, censured him, and spoke ill of him to the bishops of Lower Canada and Chicago. Chiniquy responded harshly, schemed, and criticized.

Bishop Anthony O’Regan, who had set himself the task of restoring ecclesiastical discipline in the diocese of Chicago, lost his patience and blamed Chiniquy for the dissension. He was also disturbed by certain rumours about his conduct and by his difficulties with a land speculator. Furthermore, he did not greatly appreciate the Canadians’ desire to keep to themselves and was afraid it would arouse xenophobic hostility. When he reprimanded Chiniquy and decided to move him, Chiniquy answered back. He would not budge, and spread rumours that the bishop wanted to seize his church and appoint an Irish priest, as he had done with the Canadian church in Chicago. On 19 Aug. 1856, infuriated by Chiniquy’s insubordination and the publicity surrounding all these events, O’Regan suspended him. Chiniquy begged the bishop to reconsider his decision, appealed to his compatriots, who all fell in behind him, and despite his suspension continued to say mass and administer the sacraments. On 3 September he was excommunicated.

The press in Lower Canada gave wide coverage to Chiniquy and his opponents. The bishops there feared the effects of divisiveness, believing that the schism might endanger the emigrants’ faith. They therefore urged Chiniquy to appeal to his bishop’s superior and even to the pope if he felt he had been wronged, and they called upon the parishioners not to associate with him. In November 1856, at the request of O’Regan, Bourget sent Chiniquy’s friends the abbés Isaac-Stanislas Lesieur-Désaulniers* and Louis-Moïse Brassard to St Anne, charging them with the mission of persuading him to submit to the legitimate authority and make amends for the scandal he had caused. On 9 August Chiniquy had implored Bourget to let him return to Canada and preach against emigration, adding that he could still be useful to the temperance cause. In the instructions given to Lesieur-Désaulniers and Brassard on 17 November, Bourget noted that if Chiniquy was willing to do penance, he would find a place in the diocese of Montreal, which had not forgotten all the good he had done there.

Bourget’s delegates arrived at St Anne late in November and met with Chiniquy. He agreed to write Bishop O’Regan a letter in which he submitted to his sentence, regretted the scandal caused by his actions and writings, and requested the lifting of the measures of censure imposed on him and on those who had received the sacraments from him. He would cease to exercise his ministry and would leave St Anne in three weeks. Lesieur-Désaulniers hailed the negotiations as a success, but was forced to change his tune. O’Regan made further demands and refused the act of submission. He insisted that Chiniquy publicly confess he had disobeyed the legitimate authority and explicitly retract the various false and unfounded assertions he had made and published in the newspapers. In addition he wanted Chiniquy to admit that his bishop had always acted with complete fairness towards him. Convinced that O’Regan wished to humiliate him and that his friends from Lower Canada had entrapped and betrayed him, Chiniquy went into a frenzied rage. He cursed the priests, denied that he had been suspended or excommunicated, and appealed to the people of St Anne. The majority supported him unreservedly.

At the same time as the real reasons behind Chiniquy’s departure were being revealed in Lower Canada and his mendacious writings were being banned, O’Regan named Lesieur-Désaulniers curé of Bourbonnais and asked for at least two more Canadian priests. He sought thereby to encircle Chiniquy and keep the people away from him. This strategy met with some success but in no way put an end to the problem. On 3 Aug. 1858 Bishop John Duggan, O’Regan’s successor, went to St Anne and formally reconfirmed the excommunication of Chiniquy. Rather than submit, Chiniquy left the Catholic Church, taking his followers from St Anne and various missions in Illinois with him.

At that time, as Chiniquy later recounted in his memoirs, he saw clearly that the Roman church could not be the church of Jesus Christ. The thought filled him with terror. He understood then that he had left forever relatives, friends, and motherland, and that for them he was no longer anything but an apostate, a traitor to be fought by every possible means. Where could he go to be saved? He had no friends among the Protestants, whom he had always opposed. Life seemed a burden, and it is thought that he even considered suicide. Then he had a revelation: salvation is a perfect gift freely bestowed, a gift from God, who in return asks only for love and repentance. He realized that God alone had an absolute claim on him, that he owed obedience neither to the pope nor to the bishops nor to the church. “I had only one desire left: . . . to be allowed to show my people this gift and get them to accept it.” This account of his conversion he was to expand and modify according to circumstance and audience. He was converted, that is, he adapted himself to what he had always rejected but what now seemed to him inevitable.

After observing different religious denominations and becoming convinced that joining one of the large Protestant families was preferable to being isolated, Chiniquy decided upon the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A., along with more than 2,000 followers. He was admitted as a Presbyterian minister on 1 Feb. 1860. That year he was invited to take part in the celebrations being held in Europe to mark the 300th anniversary of the Reformation, and he went to Great Britain, France, Switzerland, and Italy. He returned with enhanced prestige.

In June 1862, for reasons that are unclear but apparently connected with his disorderliness, his craving to be the centre of attention, and his mania for challenging authority, the Chicago presbytery suspended Chiniquy and then relieved him of all his ministerial duties. After an inquiry headed by the Presbyterian minister Alexander Ferrie Kemp*, the synod of the Canada Presbyterian Church accepted him as a minister, and his congregation in St Anne was admitted to the synod. These events scarcely slowed Chiniquy down. He was obviously seeking a mission worthy of his talents, as the diversity of his activities shows. He looked after St Anne, where he had to rebuild the chapel and school, which had been destroyed by fire, he preached here and there, went to Prince Edward Island, spent several months in Montreal, and published numerous articles in Protestant journals. In the Toronto Home and Foreign Record of the Canada Presbyterian Church in particular he intimated that there was a constant increase in the number of French Canadians being converted to Protestantism and that he hoped to devote his final years to evangelizing Canada, Acadia, and the United States. His mission was becoming clearer.

Chiniquy’s preaching pleased his coreligionists. It consisted of unrestrained attacks on the Catholic Church, its dogmas, sacraments, moral doctrine, and devotional practices. He made outrageous remarks about the pope, bishops, and priests. A powerful preacher able to sway crowds, he seemed the very man to entice the great mass of French Canadians away from Rome. In 1873 the synod of the Canada Presbyterian Church decided to entrust this mission to him.

During the next five years Chiniquy conducted an unremitting campaign, indefatigably preaching the same themes. He toured the Maritimes, the Canadian west, New England, and above all the province of Quebec, to which in January 1875 he returned with his family to live (he had married in 1864). He used spectacular methods, sought the sensational, narrowly escaped the vulgar. Even some Protestants became indignant. In Montreal on 30 Jan. 1876 he consecrated a number of communion wafers, crumbled them, and then trampled them underfoot to demonstrate that they were just innocuous biscuits. In 1875, at Montreal, he had published Le prêtre, la femme et le confessionnal, in which he dealt with auricular confession, his favourite subject. The confessional, he claimed, was nothing but “a school of perdition.” The immoral and shameful questions put by the confessor served to “initiate children into the mysteries of iniquity” and suggested unspeakable ideas, images, and temptations to both priest and female penitents. The confessional let the priest know which of his penitents were strong and which weak.

Chiniquy’s new crusade is thought to have led several thousand people in the province of Quebec to “abandon their errors.” Elsewhere the results were less substantial: only a few dozen became disciples of Chiniquy in New England and other places. It was not much, but it was more than enough to move French Canadian Catholics to anxiety and anger. Everywhere he went Chiniquy sowed rage and stirred up violence. On 19 March 1875 Bishop Bourget published a pastoral letter against him.

In 1878, as his lungs required care, Chiniquy was advised by doctors to go on a voyage for a rest. He spent two years visiting Australia, Tasmania, and New Zealand, and preaching against Rome. In 1880 he was back at St Anne. He set off again on a round of lectures in England in 1882, but his time was devoted principally to writing, and in particular to his memoirs. They appeared in two publications: Cinquante ans dans l’Église de Rome, published at Montreal in 1885, and Forty years in the church of Christ, published posthumously at Toronto in 1900.

Chiniquy’s memoirs, which centred on the account of his conversion, were intended for two different audiences. To the Protestants he related how, in the midst of the corruption and errors of the Catholic Church, he had been led to them and to an exemplary path as a new convert by reading the Bible, a blameless life, and the search for truth. When he addressed Catholics he was exceptionally violent. Clearly he wanted to do battle with his former friends. The account of each stage in his life furnished an opportunity to attack the Roman church, show the dissolute life supposedly led by its priests, and blaspheme against its dogmas and sacraments, among other things. His memoirs met with amazing success. In 1892 translations of the French version into nine languages were circulating. By 1898 it had reached 70 editions. All over the world bishops were seeking information from their colleagues in Quebec so that they could counter the influence of Chiniquy’s memoirs.

The stir created by Chiniquy’s writings did not disturb the serenity of his old age, which he spent surrounded by his family in Montreal, in enviable circumstances. Enjoying good health, he travelled, preaching here and there in the province and abroad. Following a brief illness he died peacefully on 16 Jan. 1899. But his death rekindled passions. A few days earlier he had politely refused to meet the archbishop of Montreal, Paul Bruchési*, who was prepared to make a final attempt to bring him back into the Catholic Church. On 23 January the Montreal Gazette published Chiniquy’s religious testament, which had been drawn up shortly before his death. It constituted a vicious indictment of the Roman church, assembling all the themes he had preached on as a Protestant minister, a final cry of rage showing that he had neither forgotten nor pardoned the wound inflicted in 1858.

[In Chiniquy (2e éd., [Trois-Rivières, Qué.], 1955), Marcel Trudel provides a detailed and critical bibliography covering the manuscript and printed works by Charles Chiniquy, the principal archival sources, and the studies that have appeared on the man and his era. He does not, however, mention the Fonds I.-S. Lesieur-Desaulniers at the Arch. du séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe (Saint-Hyacinthe, Qué.), A, Fg-9. y.r.]

ANQ-M, CE1-27, 16 janv. 1899. ANQ-Q, CE3-3, 30 juill. 1809. DOLQ, vol.1. Gaston Carrière, Histoire documentaire de la Congrégation des missionnaires oblats de Marie-Immaculée dans l’Est du Canada (12v., Ottawa, 1957–75), 10. Claude Lessard, Le séminaire de Nicolet, 1803–1969 (Trois-Rivières, 1980). J. S. Moir, Enduring witness: a history of the Presbyterian Church in Canada ([Hamilton, Ont., 1974?]). Gaston Carrière, “Une mission tragique aux Illinois; Chiniquy et les oblats,” RHAF, 8 (1954–55): 518–55.

Cite This Article

Yves Roby, “CHINIQUY, CHARLES (baptized Charles-Paschal-Télesphore),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 6, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chiniquy_charles_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chiniquy_charles_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Yves Roby |

| Title of Article: | CHINIQUY, CHARLES (baptized Charles-Paschal-Télesphore) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | January 6, 2025 |

![[Charles Paschal Télesphore Chiniquy] [image fixe] Original title: [Charles Paschal Télesphore Chiniquy] [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.5244.jpg)