Source: Link

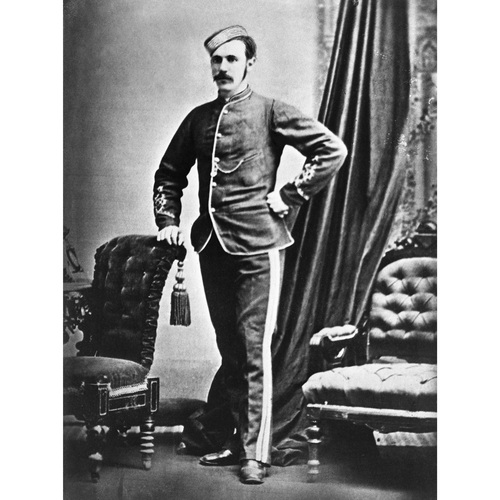

BRISEBOIS, ÉPHREM-A., soldier, NWMP officer, politician, and civil servant; b. 7 March 1850 at South Durham, Canada East, son of Joseph Brisebois, a hotel keeper and jp in Drummondville, Canada East, and Henriette Piette; m. c. 1876–80 Adelle Malcouronne, and they had no children; d. 13 Feb. 1890 in Winnipeg, Man.

Éphrem-A. Brisebois was a member of a well-educated, bilingual, and deeply religious Roman Catholic family. Though an excellent student he left school at 15 to fight with the Union Army during the final phase of the American Civil War, and then served for almost three years with other Quebec volunteers in the courageous “Devils of the Good Lord” unit of the Papal Zouaves in Italy.

In 1873, when the federal government was creating the North-West Mounted Police to bring Canadian law to the west [see Patrick Robertson-Ross], Brisebois, a highly capable soldier and a strong Conservative, was appointed one of nine commanding officers by Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald*. Brisebois helped to recruit men for the new force and led a contingent on a 110-mile march through blizzards from Port Arthur (now part of Thunder Bay, Ont.) to Lower Fort Garry (Man.). There, he trained the raw recruits all winter. On 8 July 1874, in command of one of the six divisions, and having recently been promoted inspector, he embarked on the 900-mile trek westward. At Fort Benton (Mont.), he and his superior officer James Farquharson Macleod* purchased supplies and hired legendary mixed-blood scout Jerry Potts* as a guide.

Brisebois helped erect Fort Macleod (Alta), and then, following a disagreement with Macleod, was sent with a small detachment to establish Fort Kipp (Kipp, Alta). In the summer of 1875 he took charge of building Fort Brisebois. He often clashed with Macleod, his popular superior. The winter of 1875–76 was bitterly cold, one of the worst on record, and Brisebois frequently did not punish his men when they shirked duties or disobeyed orders because of the weather. Discipline and morale deteriorated. His orders to build cabins for two interpreters in a nearby Métis camp were not carried out. He himself fell in love with a Métis girl, and in frontier fashion took her to his quarters as his common-law wife, thereby enraging Roman Catholic and Protestant missionaries alike. His expropriation of the fort’s only cook-stove to heat his draughty room was the final straw; the insubordination of the whole division approached mutiny. Brisebois was sharply criticized by his superiors and, on the suggestion of Macleod, Fort Brisebois was renamed Fort Calgary in June 1876.

Concerned with the disappearance of the buffalo which he knew would mean starvation for many Indians, he tried while at the fort to enforce strict hunting regulations. He warned in 1875 that unless these were enforced “the Buffalo will disappear in less than 10 years. These Indians will then be in a starving condition and entirely dependent upon the Canadian Government for subsistence.” Within five years the Indians had become dependent on the government for food.

In August 1876 Brisebois resigned from the NWMP and rode alone 1,200 miles to Winnipeg via Fort Edmonton and the Carlton Trail. He failed to find employment in Ottawa and returned to Quebec where he flung himself into politics against the Liberals. During a by-election in 1877 in the riding of Drummond and Arthabaska, Brisebois, according to Louis-François-Roderick Masson*, “more than any other man” contributed to the victory of the Conservative candidate, Désiré-Olivier Bourbeau, over cabinet minister Wilfrid Laurier*. Brisebois fought in three more election campaigns. In December 1880 he was appointed land titles registrar of the Little Saskatchewan district with headquarters in Minnedosa, Man. He and his bride Adelle were popular in the predominantly Anglo-Saxon Protestant Minnedosa; the snowshoe club they founded became an important part of the social life of the community and Roman Catholic church services were held in their home.

During the North-West rebellion of 1885, when a dispute between the town’s chief of police, John Cameron, and the Indians of a neighbouring reserve threatened to lead to open hostilities, Brisebois quickly organized two companies of white and Métis home guards to prevent bloodshed. He also recruited the 92nd Light Infantry Company of the Winnipeg Rifles to help suppress the insurrection led by Louis Riel; he himself joined the 65th Battalion of Rifles (Mount Royal Rifles) of Quebec, as part of the Alberta Field Force. In Alberta he served as sub-commander at Fort Edmonton which was threatened at one point by the Crees of Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa]. After the rebellion Brisebois returned to Minnedosa where he strove to make sure that Ottawa did not forget the soldiers’ services. As registrar he settled hundreds of land claims, but late in 1889 the land titles office was phased out. Unemployed, Brisebois moved to Winnipeg where a few weeks later, at the age of 39, he died of a heart attack. He was buried in the cemetery in St Boniface, Man.

PAC, RG 2, 1, P.C.988, 28 July 1874; P.C.759, 16 Aug. 1876; RG 18, A1, 610, nos.70, 96, 111; B7, 3436, regimental number O–8. Minnedosa Tribune (Minnedosa, Man.), 7 Dec. 1883–1890. H. A. Dempsey, “Brisebois: Calgary’s forgotten founder,” Frontier Calgary: town, city, and region, 1875–1914, ed. A. W. Rasporich and H. C. Klassen (Calgary, 1975), 28–40. S. W. Horrall, The pictorial history of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (Toronto, 1973). E. C. Morgan, “The North-West Mounted Police, 1873–1883” (ma thesis, Univ. of Saskatchewan, Regina Campus, 1970). P. L. Neufeld, “Brisebois: forgotten Mountie pioneer,” Canadian Frontier Annual (Surrey, B.C.), 1977: 80–83.

Cite This Article

Peter L. Neufeld, “BRISEBOIS, ÉPHREM-A.,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brisebois_ephrem_a_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brisebois_ephrem_a_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter L. Neufeld |

| Title of Article: | BRISEBOIS, ÉPHREM-A. |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | April 2, 2025 |