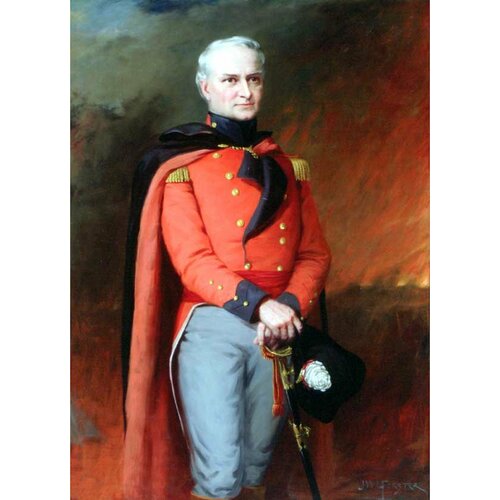

![Description English: Æneas Shaw Artist: FORSTER, John Wycliffe Lowes (J.W.L) Title: Major-General The Hon. Aeneas Shaw [Member of Leg Council UC, 1794; Adjutant General, War of 1812] Date: c. 1902 Source: Archives of Ontario Date 2007-10-26 (original upload date) Source Transferred from en.wikipedia; Transfer was stated to be made by User:Undead_warrior. Author Original uploader was YUL89YYZ at en.wikipedia Permission (Reusing this file) PD-CANADA.

This image is available from the Archives of Ontario This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing for more information. English | Français | Македонски | +/−

Original title: Description English: Æneas Shaw Artist: FORSTER, John Wycliffe Lowes (J.W.L) Title: Major-General The Hon. Aeneas Shaw [Member of Leg Council UC, 1794; Adjutant General, War of 1812] Date: c. 1902 Source: Archives of Ontario Date 2007-10-26 (original upload date) Source Transferred from en.wikipedia; Transfer was stated to be made by User:Undead_warrior. Author Original uploader was YUL89YYZ at en.wikipedia Permission (Reusing this file) PD-CANADA.

This image is available from the Archives of Ontario This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing for more information. English | Français | Македонски | +/−](/bioimages/w600.6979.jpg)

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

SHAW, ÆNEAS, army officer, politician, office holder, and militia officer; b. at Tordarroch House, Scotland, second son of Angus Shaw, chief of Clan Ay, and Anne Dallas of Cantray; m. first Ann Gosline, and they had ten children; m. secondly Margaret Hickman; d. 6 Feb. 1814 in York (Toronto), Upper Canada.

Æneas Shaw emigrated to Staten Island, N.Y., about 1770. Soon after the outbreak of the American revolution he joined the Queen’s Rangers as an ensign, and ended the war as a captain, his promotions beginning in November 1777 when a new commander, John Graves Simcoe, formed a Highland company. Judged adept in the training of light infantry and sharpshooters, he saw much detached service in the Pennsylvania and Virginia campaigns. After surrendering at Yorktown, Va, in 1781, he was evacuated to New York City, and he subsequently joined the loyalist migration to Nova Scotia. He settled on the Nashwaak River (N.B.), where by the fall of 1791 he was an established farmer.

Nevertheless Shaw accepted a commission as a captain-lieutenant in the Queen’s Rangers when they were raised as a provincial corps for Upper Canada. Of the five old Rangers who composed half of the new regiment’s officers, Shaw was the one who most clearly left a secure position in civilian life. He travelled overland with a dozen recruits to meet Lieutenant Governor Simcoe at Quebec in March 1792 and led the first contingent of Rangers up to Kingston. A year later, when Simcoe had already recommended his appointment to the Executive Council, he brought his family to Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake). In Simcoe’s words, he was a man of “Education, Ability, & Loyalty . . . one of those Gentlemen who is most likely to effect a permanent Landed Establishment in this Country.”

Shaw commanded the Ranger detachment that cleared the site of York in 1793 and he was among the first officials to move his family there. He would have commanded a garrison at Long Point as a nucleus for loyal settlement, if the project had been approved by the imperial government. Delays by the same authority prevented him from being sworn in as an executive councillor until June 1794. In the same month he also took a seat on the Legislative Council, in time to support the administration’s bill for a court of king’s bench. From then on, although his only other civil appointment was as lieutenant of the county of York (26 Aug. 1796 to 2 Dec. 1798), he was more an official than an officer. He and Receiver General Peter Russell were the only regular attendants at the Executive Council under Simcoe. He was a reliable supporter not only of his patron but also of Russell when the latter became administrator of the province in 1796. Concerned that Shaw’s regiment might be withdrawn from Upper Canada, Russell asked permission to have him remain at York because of his indispensability as a councillor. On 31 Aug. 1799 Lieutenant Governor Peter Hunter, when forming a committee of the council to conduct affairs during his frequent absences, included Shaw; but seniority and his residence at York were probably sufficient reasons. Shaw had neither raised trouble nor made a mark in either council, but his association with Russell was no longer an advantage. His influence on the Executive Council was being eclipsed by the rise of later appointees, notably John McGill*. When the Queen’s Rangers were disbanded in 1802, he retired on half pay as a lieutenant-colonel. In the next year his membership in the council became honorary and lasted as such until 1807.

Shaw’s public career was not over. Fear of war with the United States, arising from the Chesapeake affair [see Sir George Cranfield Berkeley], revealed that the Upper Canadian militia was almost without arms or training and that its adjutant general, Hugh McDonell* (Aberchalder), was gravely ill. An energetic officer, Sir James Henry Craig, came out in late 1807 to fill the vacant post of commander-in-chief at Quebec. In addition, the Upper Canadian militia was provided with 4,000 muskets, a new militia act of 16 March 1808 made it liable for service in defence of the lower as well as the upper province, and Shaw was gazetted on 2 Dec. 1807 with the local rank of colonel to succeed McDonell. Promoted major-general in 1811, Shaw was responsible for training the militia. It was the largest military force in the province, with about a tenth of the total white population enrolled, but it was not subject to training in units larger than local companies nor to fixed periods of service in case of war. Flank companies of volunteers were provided for by a militia act of 6 March 1812, and 2,000 men were subsequently registered in them. Even they could be obliged to train for no more than three days a month. Since the legislature specifically refused to strengthen the law, Shaw can hardly be blamed for the deficiencies of militia units when war came in June 1812. He led them in action once, at the unsuccessful defence of York on 27 April 1813. Nearing his final illness and 32 years away from combat, he moved them too slowly to be of use and unnecessarily withdrew a critically placed company of regulars to their support.

The status that Shaw found in Upper Canada came from office, not wealth. The scale of land grants attached to his rank allowed him 6,000 acres for himself and 1,200 more for each of his children. Nearly all of this land remained unproductive during his lifetime. He began selling it in 1803 at prices that suggest he needed money: his 1,900 acres in Pickering and West Flamborough townships, sold mostly to William Allan*, brought him only £642. About half his grant, in North Dorchester Township, became part of Thomas Talbot*’s settlement. When in 1817 his widow petitioned for the support of his children, however, she was far from poor. Shaw had kept the most valuable of his 500 acres in York Township, and some of it remained in the family until 1862.

[The Shaw family papers, in private hands, are chiefly genealogical. Contemporary references to Shaw are in P. Campbell, Travels in North America (Langton and Ganong); Corr. of Hon. Peter Russell (Cruikshank and Hunter); Corr. of Lieut. Governor Simcoe (Cruikshank); Select British docs. of War of 1812 (Wood); [J. G.] Simcoe, A journal of the operations of the Queen’s Rangers, from the end of the year 1777, to the conclusion of the late American war (Exeter, Eng., [1787]); and Gwillim, Diary of Mrs. Simcoe (Robertson; 1911; 1934). There are copies of primary documents relating to Shaw in Ont., Ministry of Citizenship and Culture, Heritage Administration Branch (Toronto), Hist. sect. research files, Toronto RF.31, Aeneas Shaw. See also Chadwick, Ontarian families and W. J. Rattray, The Scot in British North America (4v., Toronto, 1880–84). s.r.m.]

Cite This Article

S. R. Mealing, “SHAW, ÆNEAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/shaw_aeneas_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/shaw_aeneas_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | S. R. Mealing |

| Title of Article: | SHAW, ÆNEAS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2025 |