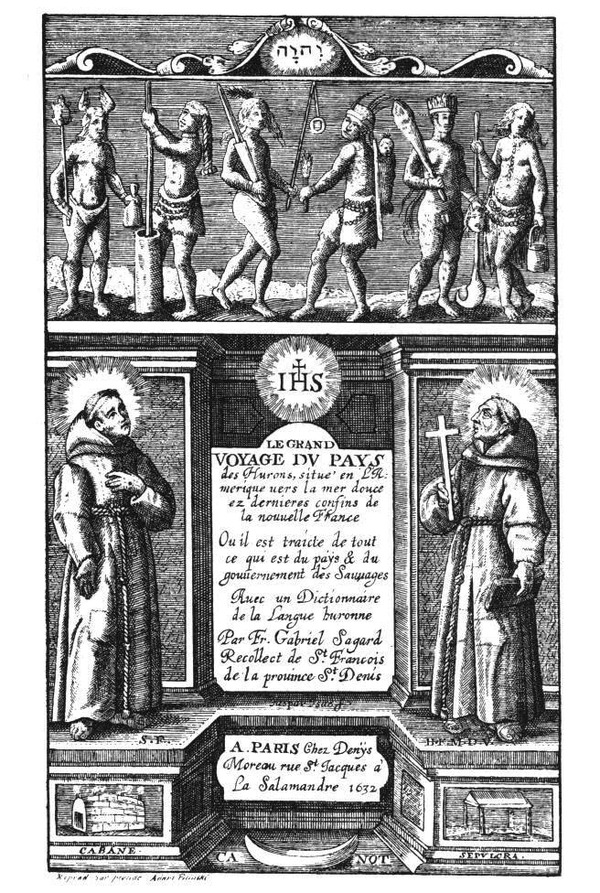

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

SAGARD, GABRIEL (baptized Théodat), Recollet friar, missionary in the Huron country in 1623 and 1624, first religious historian of Canada; fl. 1614–36.

From an allusion by Sagard to Father Daniel Saymond (d. 1604), superior of the monastery of Verdun, we may conclude that Sagard was already a Recollet by that year. At the end of 1614 he was living in Paris with Father Jacques Garnier Chapouin, the provincial of the Recollets of Saint-Denis, and serving as his private secretary. At that time Louis Houel, a king’s secretary and comptroller of the salt-works at Brouage, suggested to Father Chapouin that missionaries be sent to New France. Father Chapouin, encouraged by the French clergy, who were assembled for the Estates General, immediately appointed four religious: Denis Jamet, Jean Dolbeau, Joseph Le Caron, and Pacifique Duplessis. They left in the spring of 1615: “. . . I should have dearly liked to be one of them,” wrote Sagard. His wish was not to be fulfilled until 1623, at which time he obtained permission to sail to Canada with Father Nicolas Viel. The two Recollets left the monastery in Paris on 18 March and landed at Quebec on 28 June, after a crossing of “three months six days of sailing.”

As soon as they arrived, the missionaries made plans to get to the Huron country. On 16 July Fathers Viel and Le Caron and Brother Sagard left the convent of the Recollets; they joined the French boats leaving for the exchange of furs, which took place that year at Cap-de-la-Victoire, at the mouth of the Rivière des Iroquois (Richelieu). When the trading was finished (2 August), the Hurons returned to their territory together with the three missionaries, who were each in a different canoe. After a most arduous journey Sagard reached Lake Huron on 20 August. Two days later he was at Ossossanë, the village of his guide and protector, Oonchiarey.

Sagard passed “a fairly long time” in this environment; he was respected and loved as a guest, and divided his time between prayer, the study of the language, and the visiting of families. One day Father Viel suddenly arrived. Together they rejoined Father Le Caron at Carhagouha, some five leagues from Ossossanë. The Hurons helped the three Recollets build near the village a cabin in their style; it measured “about 20 feet long and 10 or 12 wide, being constructed in the form of a garden bower.” It was in this little convent that the Recollets exercised their ministry, celebrating the holy mysteries, administering the sacraments to the French, and continually receiving numerous Hurons. Of these, some came to obtain religious instruction; others, more “spiteful,” came “to steal our modest furnishings under pretext of paying us a visit.”

Around May 1624 Sagard, together with the Hurons who were going to exchange furs, set off for Quebec in order to acquire certain items necessary for the mission. On the way, they met the convoy headed by Étienne Brûlé, which was also travelling in the direction of the St. Lawrence valley. The boats of the missionaries reached Quebec on 16 July, after a number of vicissitudes. As he was about to return, Sagard received a letter from the provincial, Father Polycarpe Du Fay, instructing him to come back to Paris.

Some months after the publication of his Histoire (1636), Sagard left the Recollets. They made repeated attempts to get him to join them again, but to no purpose, since Sagard died, probably while with the Franciscans.

Three works of Sagard, dealing with the early days of New France, have come down to us. Le grand voyage du pays des Hurons (1632) appeared in two volumes. Six chapters recount the ocean crossing, the journey from Quebec to the “lac des Hurons,” and the author’s return to France. The remainder of the work examines the Huron customs and way of life, and the flora and fauna of the country. It is a brilliant, astonishingly precise fresco.

Four years later Sagard published L’histoire du Canada in four parts. The first deals with the apostolic activity of the Recollets in Canada from 1615 up to the author’s journey in 1623; the two following parts reproduce Le grand voyage, revised and enlarged; the last is concerned with the period marked by the arrival of the Jesuits, the capture of Quebec, and the temporary abandonment of the colony. In addition to describing missionary life, the author relates the principal political, commercial, and agricultural events in which the Recollets played a part. It is an important work which corroborates and adds further detail to the writings of Samuel de Champlain, and which provides us with a number of unique and outstandingly valuable documents.

At first sight the book is disconcerting: the historian takes up and amplifies his study of 1632, giving us information on the missionary work of the Recollets in the Holy Land, India, Tartary, Slavonia, Bulgaria, China, and America. The object of this panoramic view is to establish the injustice of excluding the Recollets when Canada was returned to the French in 1632. Sagard wants to prove, on the one hand, that the success of the Recollets as apostles in other countries is an argument in favour of their return to Canada, and to show on the other hand that the apparent failure of the first missionaries was owing to the ill will of the companies for trading and colonizing and the disgraceful conduct of certain French settlers. A plea pro domo, perhaps, but in no way an extravagant panegyric. On the contrary, the eulogy has an attractive tone to it: the thesis appears only as a finely interwoven thread, and the monk uses a sly wit with great finesse.

The “Dictionnaire de la langue huronne” is a collection of French expressions translated into the Huron language. One can hold against Sagard – and several have not failed to do so – the fact that this so-called dictionary is not a dictionary, and that it contains errors. Sagard never had any pretentions in this respect. He was thoroughly aware of undertaking an irksome task: he acknowledged that the language was very difficult, had few if any rules, and was constantly changing. If, however, he tackled this thankless job, it was because of his earnest desire to supply those who were labouring to implant faith among the Hurons with the rudiments of the language. Nothing is likely to cast serious doubt on the value of this short work. Sagard draws upon the experience of interpreters, and upon that of his missionary associates, among them Father Le Caron, the author of a Huron dictionary now lost. Despite its imperfections, Sagard’s dictionary has long remained, in the opinion of one linguist, the most complete compilation dealing with the old Huron language.

The qualities of the historian inspire confidence: “keenness of observation, strict accuracy, sincerity, straightforward simplicity.” His work is founded upon authentic sources: letters and relations by his associates, ecclesiastical and civil documents, reports by Jesuits. In addition he uses Champlain’s writings, from which he reports several facts without naming Champlain, and those of Marc Lescarbot, whom he mentions once under the name of “Lescot.” Finally, Sagard recounts and describes events which to a large extent he witnessed himself.

As a historian he has been reproved for a credulousness which some have called extreme. Somewhat unlikely cases of possession by demons and of diabolical apparitions, with which certain chapters are concerned, are an indication of an undeniable credulousness. Is he to be condemned because of that? We must not forget the period when Sagard was writing, a period when a fervour not firmly established lent too-ready credence to spells and interventions by the devil. In any case, great writers of the same period have hardly displayed any more caution.

Sagard is first and foremost a painter, who applies himself to the detail of things, to daily life. He is helped by a faculty for keen observation. Whether he is studying the habits and customs of the Hurons, or tracing the topography of places, or describing the flora and fauna of the region, Sagard is precise and exact. These qualities are enhanced by an attractive form of expression and by a direct, smoothly flowing style, although there are some blemishes. Other narrators have a more elegant, refined prose; very few possess his completely uninhibited, natural, simple manner.

Gabriel Sagard continues to be a little-known figure whom our annals are wont to pass over. Even in the restricted circle of scholars, Sagard does not enjoy the esteem of all. For some, this worthy monk is only a naïve person, with a superficial and over-credulous mind; for others, he is a first-rate historian, with a mind that is discerning and luminous. But the fact remains that Sagard’s work, devoted to the early days of New France, commands respect: the author is a reliable, competent, and honest witness.

Sagard, Le grand voyage (Tross); Histoire du Canada (Tross), see particularly introductory note by H.-Émile Chevalier; Long journey (Wrong and Langton). J.-C. Cayer, “Gabriel Sagard, Théodat,” in Centenaire de l’histoire de François-Xavier Garneau (Montréal, 1945), 171–200. Archange Godbout, “L’historien Sagard,” in Les Récollets et Montréal (Montréal, 1955), 89–97. Jouve, Les Franciscains et le Canada (1615–1629). Séraphin Marion, Relations des voyageurs français en Nouvelle-France au XVIIe siècle (Paris, 1923). H.-A. Scott, “Que penser de l’historien du Canada, le frère Gabriel Sagard, récollet?” Almanach de Saint-François (Montréal, 1924), 40–44.

Cite This Article

Jean de la Croix Rioux, “SAGARD, GABRIEL (baptized Théodat),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 4, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sagard_gabriel_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sagard_gabriel_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean de la Croix Rioux |

| Title of Article: | SAGARD, GABRIEL (baptized Théodat) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | April 4, 2025 |