Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

VANCOUVER, GEORGE, naval officer and explorer; b. 22 June 1757 at King’s Lynn, England, sixth and youngest child of John Jasper Vancouver, deputy collector of customs at King’s Lynn and a descendant of the titled Van Coeverden family, one of the oldest in Holland, and Bridget Berners, daughter of an old Essex and Norfolk family that traced its ancestry back to Sir Richard Grenville of Revenge fame; d. 12 May 1798 at Petersham (Greater London), England.

George Vancouver entered the Royal Navy in 1771. Some person with influence evidently brought him to the attention of James Cook, then preparing for the second of his three great voyages of discovery, for in January 1772 Cook appointed Vancouver to his ship, the Resolution. Though he had the nominal rank of able-bodied seaman, Vancouver was actually a midshipman-in-training. William Wales, a noted astronomer, was a supernumerary on board, and Vancouver was privileged to receive instruction under him. The voyage, in search of the legendary southern continent, lasted three years and ventured as far south as 71°10’.

In February 1776 Cook appointed Vancouver a midshipman on the Discovery, which was to accompany the Resolution on his third expedition, sent out in search of a Pacific outlet to the fabled northwest passage. The ships arrived off the northwest coast of America in March 1778. Vancouver’s shipmates included Joseph Billings*, George Dixon, and Nathaniel Portlock*, all of whom later commanded trading vessels that visited this coast. When Cook happened upon King George’s Sound (Nootka Sound, B.C.) on 29 March and refitted there, Vancouver and his shipmates became the first Europeans known to have landed on the coast of what is now British Columbia [see Juan Josef Pérez Hernández]. After exploring the coast well to the north, Cook sailed to the Sandwich (Hawaiian) Islands, where he was killed in a clash with the natives on 14 Feb. 1779. Vancouver had narrowly escaped a like fate the previous day. The expedition returned to England in October 1780, and on the 19th Vancouver passed the examination for lieutenant. His eight years’ service with Cook had given him an incomparable opportunity to receive training in seamanship and hydrographic surveying under the greatest navigator of the age.

Vancouver’s career falls into three well-defined periods: first, the years with Cook, then nine years in fighting ships, and finally, the voyage of discovery. The middle period was spent almost entirely in the Caribbean. On 9 Dec. 1780 he was appointed to the sloop Martin, which was sent to the West Indies early in 1782. In May he joined the much larger Fame (74 guns) and served in her until peace was proclaimed and she returned to England in July 1783. The end of hostilities meant that many ships were decommissioned, and Vancouver found himself on half pay for the next 15 months. In November 1784 he was appointed to the Europa (50 guns), flagship of Admiral Alexander Innes, the new commander-in-chief of the Jamaica station. The death rate in the West Indies from yellow fever and other diseases was appalling, but the vacancies resulting from deaths often provided opportunities for promotion. Early in 1787 Admiral Innes died and was succeeded by Commodore Alan Gardner, an energetic and progressive officer, destined to rise rapidly in the service and to become a member of the Board of Admiralty early in 1790. He also became Vancouver’s friend and influential patron, and deaths enabled him to promote Vancouver second lieutenant of the Europa in November 1787 and first lieutenant (second in command) two months later. In 1789, after a five-year cruise, the Europa headed for home waters, where Vancouver was paid off in mid September.

At this time interest in the Pacific was increasing sharply. Southern whaling was attracting attention, and settlement had just begun in New Holland (Australia). But it was the northwest coast of North America that was of most immediate concern to Great Britain. Sea otter skins picked up casually by the crews of Cook’s ships had brought high prices in China, and when this fact became known trading vessels began to frequent the coast [see James Hanna; John Kendrick]. Britain was interested in the commercial opportunities the fur trade might offer and was not prepared to accept Spain’s contention that she held exclusive title to the whole coast from San Francisco to Prince William Sound (Alas.). In addition, the Admiralty was anxious to find out once and for all whether or not a passage existed between the Pacific and the Atlantic. Cook had proved that there was none of commercial value north of 55°N. The possibility remained, however, that Alaska might be a vast island, made so by a passage farther south.

In the autumn of 1789 it was decided to send an expedition to settle the question. A suitable ship of 340 tons burthen was purchased, named Discovery, and commissioned on 1 Jan. 1790. The command was given to Captain Henry Roberts, who, like Vancouver, had sailed with Cook on his second and third voyages. Through Gardner’s influence, Vancouver was appointed second in command.

The work of outfitting the Discovery was well advanced when details of the famous Nootka Sound affair reached London. The seizure of several British ships there in time of peace, by the Spanish commander Esteban José Martínez, was denounced as an insult to the nation’s honour, and Spain’s claim to have the right to exclude foreign traders from the area was hotly denied. A powerful naval squadron was mobilized and Britain prepared energetically for war. Spain was in no position to fight and was forced to agree to the Nootka Sound Convention, signed on 28 Oct. 1790 in Madrid. Under its terms Spain was to make restitution to British subjects whose property had been seized, and, more important, to abandon her claim to exclusive ownership and occupation of the coast.

Mobilization had halted the outfitting of the Discovery; in May her officers and crew had been assigned to fighting ships. Roberts had gone to the West Indies and Vancouver had joined the Courageux, commanded by Gardner. When news of the signing of the convention was received early in November, preparations for the expedition to the Pacific were resumed immediately. On the 17th Vancouver was recalled to London, and on 15 December, no doubt on Gardner’s recommendation, he was appointed to command the Discovery.

His instructions, dated 8 March 1791, dealt with two matters in addition to the survey of the coast. First, he was to receive from Spanish officers at Nootka “such lands or buildings as are to be restored to the British subjects”; secondly, he was to winter in the Sandwich Islands and while there complete a survey of them. As for the main purpose of the voyage, he was to examine the coast between 30° and 60°N and to acquire “accurate information with respect to the nature and extent of any water-communication” which might “in any considerable degree” serve as a northwest passage “for the purposes of commerce.” The Discovery, accompanied by the small armed tender Chatham (131 tons), sailed from Falmouth, their last port of call in England, on 1 April 1791. The voyage to the northwest coast was to last over a year and was made by way of Tenerife (Canary Islands), the Cape of Good Hope, New Holland, New Zealand, Tahiti, and the Sandwich Islands. Vancouver had expected to meet a supply ship, the Daedalus, in the Sandwich Islands, but she failed to appear. He sailed on to his main objective, the coast of North America, which was sighted on 17 April 1792. The landfall was in latitude 39°27’N, about 110 miles north of San Francisco.

Sailing north, he began the survey that he was to continue through all the complexities of the coastline to a point beyond 60°. Juan de Fuca Strait, to which he had been directed to give particular attention, was reached on 29 April. Vancouver has been much criticized for his failure to enter the Columbia River, the mouth of which he passed as he sailed northward; it is evident, however, that he suspected its existence but decided to leave it for later examination. Indeed, he paid little attention to rivers, since the mountains visible in the distance made it highly unlikely that they would be navigable for any considerable distance inland. Moreover, he had been directed, in order to save time, “not to pursue any inlet or river further than it shall appear to be navigable by vessels of such burthen as might safely navigate the pacific ocean.”

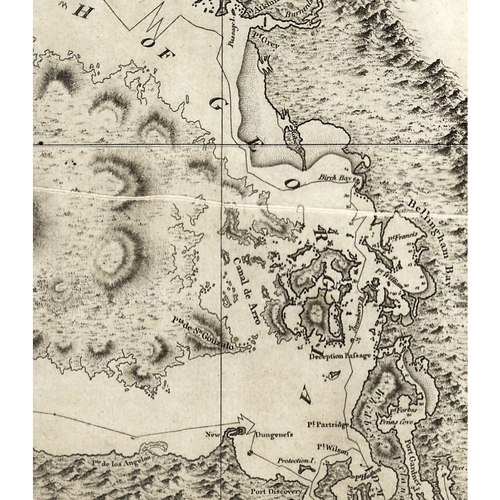

His plan for the survey was simple: he would trace every foot of the continental shore, so that no passage could escape him. The featureless coasts of what are now Oregon and Washington were easily surveyed, but the shore north of Juan de Fuca Strait was another matter. Vancouver first realized the difficulties of his task when he explored the maze of inlets branching off Puget Sound (Wash.). The Admiralty had sent the Chatham with the Discovery in the expectation that the smaller ship could survey narrow waters into which it would be imprudent for the Discovery to venture; but Vancouver quickly learned that tidal and wind conditions, and often sheer depth of water that placed the bottom beyond the reach of an anchor, created hazards even for the Chatham, and he was compelled after a month’s experience to fall back on the ships’ pinnaces, cutters, and launches, however laborious and dangerous service in open boats might be. Once the Discovery and Chatham had found a suitable anchorage the boats would set out to explore the adjacent coastline. Every inlet was traced to its head, lest it form part of the long sought northwest passage. The boats were usually provisioned for a week or ten days, but officers and men alike made every effort to extend the period if by so doing they could advance the survey. A great effort was made to treat the natives fairly and establish friendly relations with them. The boats, however, being no larger than many Indian canoes, were temptations because of their arms and provisions, and late in the survey a number of attacks had to be beaten off.

As long as his health permitted, Vancouver often took part in the boat expeditions. On 22 June 1792, when returning to the ships after exploring Howe Sound, Jervis Inlet, and what is now Vancouver harbour, he found the Spanish survey ships Sútil and Mexicana, under the command of Dionisio Alcalâ-Galiano*, at anchor off Point Grey. From Alcalâ-Galiano he learned that Spanish explorers had preceded him in Juan de Fuca Strait and the Strait of Georgia, though not in Puget Sound. Relations were cordial and some cooperation was decided upon, but it was limited by Vancouver’s contention that his instructions prevented him from accepting any but his own survey of the continental shore.

By August Vancouver had worked his way up the full length of what is now Vancouver Island, establishing its insularity when his ships emerged in Queen Charlotte Sound on 9 August. He pushed on to Burke Channel, in 52°N, and then sailed south to Nootka Sound where he knew his supply ship and the Spanish commander, Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra, were awaiting him.

A warm friendship sprang up between Vancouver and Bodega, but they were unable to agree on the details of the property transfer provided for in the Nootka Convention. Vancouver had expected to receive an extensive area, perhaps the entire sound; inquiry had convinced Bodega that John Meares*, part owner of several of the ships seized in 1789, had occupied no more than a small plot on Friendly Cove. Both undertook to refer the matter to their respective governments and await instructions. The supply ship brought Vancouver some additional instructions dated 20 Aug. 1791, but he received no further communication from the Admiralty during the last three years of his voyage.

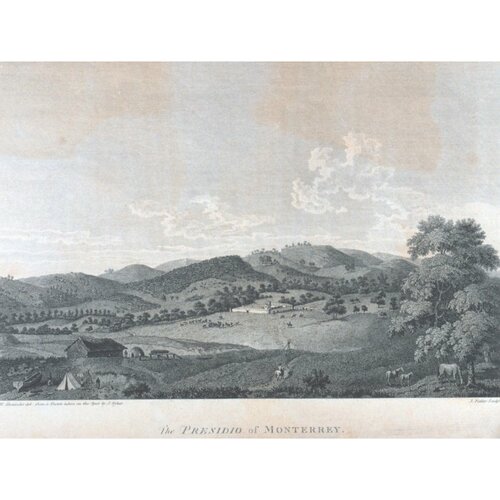

From Nootka Vancouver sailed south to San Francisco and Monterey, in Alta (present-day) California, and then to the Sandwich Islands where he wintered. In May 1793 he was back on the coast and by September had traced the continental shore as far north as 56°. Vancouver explored Dean Channel in June; a few weeks later he would have met Alexander Mackenzie*, who completed his overland journey to the Pacific there late in July.

At the end of the 1793 season Vancouver again visited Alta California en route to winter quarters in the Sandwich Islands. After calling at Monterey he went on to San Diego and then, fulfilling his instructions, sailed southward along the Mexican coast to extend his survey to the appointed limit of 30°. In two seasons he had thus traced the coast from 30°N to 56°N and had proved that Juan de Fuca Strait was not the entrance to a great inland sea, as Fuca* had alleged, and that the extensive waterways Bartholomew de Fonte* claimed to have entered in latitude 53° did not exist.

In the course of his third and last visit to the Sandwich Islands Vancouver completed their survey and also intervened actively in their internal affairs. With a view to ending civil strife he encouraged their political unification under King Kamehameha. He also persuaded Kamehameha to cede the island of Hawaii to Great Britain in the expectation that a small military force would be stationed there to provide protection for the islands, now that ships of many nations were frequenting them. The cession was signed on 25 Feb. 1794, but no confirming action was taken in London.

For the 1794 season Vancouver decided to sail directly to Cook Inlet (Alas.), the northern limit of his survey, and to work southward to the point reached the previous year. The last anchorage of the Discovery and Chatham was in a bay on the southeast coast of Baranof Island to which Vancouver gave the appropriate name Port Conclusion. The boats returned from the last exploring expedition on 19 August, and the completion of the survey was celebrated by “such an additional allowance of grog as was fully sufficient to answer every purpose of festivity on the occasion.” Later Vancouver was to write in his Voyage of discovery to the north Pacific ocean: “I trust the precision with which the survey . . . has been carried into effect, will remove every doubt, and set aside every opinion of a north-west passage, or any water communication navigable for shipping, existing between the north pacific, and the interior of the American continent, within the limits of our researches.”

The survey had been carried out with remarkable accuracy. Vancouver’s latitudes vary little from modern values; the more difficult calculations for longitude show an error that varies from about one-third to one degree. It was an accomplishment worthy of comparison with the surveys of Cook, and the frequent references to Cook in the published Voyage show that he was ever the ideal Vancouver had in mind. John Cawte Beaglehole, the authority on Cook, remarks that of all the men who trained under him Vancouver was “the only one whose work as a marine surveyor was to put him in the class of his commander.”

The long homeward voyage was made by Cape Horn, with calls at Monterey, Valparaiso (Chile), and St Helena. As Britain was at war, the Discovery travelled from St Helena in convoy and arrived in the estuary of the Shannon River, Ireland, on 13 Sept. 1795. Vancouver left her immediately and proceeded to London but rejoined her when she arrived in the Thames on 20 October. Thus ended the longest surveying expedition in history – over four and a half years. The distance sailed was approximately 65,000 miles, to which the boat excursions are estimated to have added 10,000 miles. The care Vancouver devoted to the health of his crews was noteworthy; only one man died of disease. Another died of poisoning and four were drowned.

Vancouver’s achievement received little recognition at the time, largely because of charges that he had been overly harsh as a commander. As early as January 1793 Thomas Manby, master’s mate of the Chatham, wrote privately that Vancouver had “grown Haughty Proud Mean and Insolent, which has kept himself and Officers in a continual state of wrangling during the whole of the Voyage.” His difficulties with Archibald Menzies*, botanist and surgeon, had serious consequences because Menzies was a protégé of Sir Joseph Banks*, the influential president of the Royal Society of London. More serious was the case of Thomas Pitt, heir of Lord Camelford, one of the midshipmen-in-training in the Discovery. He was a difficult and unbalanced young man whose conduct so infuriated Vancouver that he discharged him in Hawaii in 1794. Pitt was closely related to the prime minister and to the first lord of the Admiralty, John Pitt, and a brother of Lady Grenville, wife of the foreign secretary, and their combined displeasure weighed heavily on Vancouver. It is evident that illness (probably some hyperthyroid condition) had made Vancouver irritable and subject to outbursts of temper, but he was not a brutal commander. He ran a taut ship, as was essential in a vessel far removed from any supporting authority, and if his officers did not like him, they respected him and admired his capability.

Vancouver retired on half pay in November 1795. He settled at Petersham, near Richmond Park, and was soon busy revising his journal for publication. He died, at the early age of 40, when the narrative, half a million words in length, was within a hundred pages of completion. His brother John finished the revision and the Voyage was published in 1798 in a handsome edition consisting of three quarto volumes and a folio atlas.

Almost all of the several hundred place names bestowed by Vancouver on physical features have been retained. Most notable of them is Vancouver Island, originally named Quadra and Vancouver’s Island in honour of his friend the Spanish commander. Vancouver’s work and memory have received more attention in recent years, and his grave in St Peter’s churchyard in Petersham is the scene of an annual commemorative ceremony sponsored by the province of British Columbia.

[A portrait in the National Portrait Gallery (London), long stated to be a likeness of Vancouver, is now regarded as of doubtful authenticity. No other portrait has come to light. Vancouver’s original journals, including the partial copies sent to the Admiralty while his voyage of discovery was in progress, have disappeared. His logs as lieutenant in the Martin, Fame, and Europa are in the National Maritime Museum, ADM/L/M/16B, log of hms Martin, 9 Dec. 1781–16 May 1782; ADM/L/F/115, log of hms Fame, 17 May 1782–3 July 1783; ADM/L/E/155, log of hms Europa, 24 Nov. 1787–23 Nov. 1788. His letters to the Admiralty are in PRO, Adm. 1/2628–30. His original dispatches are in PRO, CO 5/187. Drawings and charts relating to the voyage are in Ministry of Defence, Hydrographer of the Navy (Taunton, Eng.), 226, 228–29, 523 (surveys on the west coast of North America).

Most of the score or more officers’ official logs in the PRO are concise and devoted chiefly to ships’ movements and business, but two are highly informative. (1) Peter Puget, PRO, Adm. 55/ 17 and Adm. 55/27, January 1791–March 1794 (BL, Add. mss 17542–45 includes rough drafts of Puget’s journals and logs for January 1791–December 1793; Add. mss 17552, papers relating to the voyage of the Discovery and Chatham, 1790–95, includes some Vancouver letters and a narrative by Puget, one page of which was wrongly described by G. S. Godwin as the only surviving fragment of Vancouver’s original journal). (2) James Johnstone, PRO, Adm. 53/335, which unfortunately covers only the period January 1791–May 1792. There are three important private journals. (1) Archibald Menzies, BL, Add. mss 32641, December 1790–February 1794; National Library of Australia (Canberra), mss 155, Archibald Menzies, Journal, 21 Feb. 1794–18 March 1795. (2) Edward Bell, National Library of New Zealand, Alexander Turnbull Library (Wellington), [Edward Bell], Journal of voyage in H.M.S. “Chatham” to the Pacific Ocean, 1 Jan. 1791–26 Feb. 1794. (3) Thomas Manby, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University (New Haven, Conn.), Western Americana coll., Thomas Manby, Journal of the voyage of H.M.S. Discovery and Chatham, under the command of Captain George Vancouver, to the northwest coast of America, February 10, 1791, to June 30, 1793; University of B.C. Library (Vancouver), Special Coll. Division, Thomas Manby to Captain Barlow, 9 Jan. 1793 (photocopy). State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library (Sydney, Australia), Banks papers, Brabourne coll., v.9, includes correspondence, drafts, etc., relating to Vancouver’s voyage. There are other Banks papers in California State Library, Sutro Library (San Francisco), Sir Joseph Banks coll.

[George Vancouver], A voyage of discovery to the north Pacific Ocean, and round the world . . . , [ed. John Vancouver] (3v. and atlas, London, 1798; repr. Amsterdam and New York, 1967; new ed., [ed. John Vancouver], 6v., London, 1801). Translations were published in French (3v. and atlas, Paris, [1799–1800]); Danish (2v., Copenhagen, 1799–1802); and Russian (6v., St Petersburg, 1827–38). Abridged editions appeared in German (2v., Berlin, 1799–1800) and Swedish (2v., Stockholm, 1800–1). As well, an annotated edition of the Voyage is in preparation for the Hakluyt Society. For a complete list of previous editions see Navigations, traffiques & discoveries, 1774–1848: a guide to publications relating to the area now British Columbia, comp. G. M. Strathern and M. H. Edwards (Victoria, 1970), 308–10. E. S. Meany, Vancouver’s discovery of Puget Sound: portraits and biographies of the men honored in the naming of geographic features of northwestern America (New York and London, 1907; repr. 1915; Portland, Oreg., 1942; repr. 1949), reprints the Voyage for the period April to October 1792. [George Vancouver], Vancouver in California, 1792–1794: the original account, ed. M. [K.] E. Wilbur (3v., Los Angeles, 1953–54), reprints the portions for 1792, 1793, and 1794 that describe the visits to California.

Bern Anderson, Surveyor of the sea: the life and voyages of Captain George Vancouver (Seattle, Wash., 1960; repr. Toronto, 1966). G. H. Anderson, Vancouver and his great voyage: the story of a Norfolk sailor, Captain Geo. Vancouver, R.N., 1757–1798 (King’s Lynn, Eng., 1923). G. [S.] Godwin, Vancouver; a life, 1757–1798 (London, 1930; repr. New York, 1931). J. S. and Carrie Marshall, Vancouver’s voyage (2nd ed., Vancouver, 1967). C. F. Newcombe, The first circumnavigation of Vancouver Island (Victoria, 1914). H. R. Wagner, The cartography of the northwest coast of America to the year 1800 (2v., Berkeley, Calif., 1937); Spanish explorations in the Strait of Juan de Fuca (Santa Ana, Calif., 1933). Glyndwr Williams, The British search for the northwest passage in the eighteenth century (London and Toronto, 1962). Adrien Mansvelt, “Vancouver: a lost branch of the Van Coeverden family,” British Columbia Hist. News (Vancouver), 6 (1972–73), no.2, 20–23, and his articles “The original Vancouver in old Holland,” Vancouver Sun, 1 Sept. 1973, 37, and “Solving the Captain Vancouver mystery,” Vancouver Sun, 1 Sept. 1973, 36. w.k.l.]

Cite This Article

W. Kaye Lamb, “VANCOUVER, GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/vancouver_george_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/vancouver_george_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | W. Kaye Lamb |

| Title of Article: | VANCOUVER, GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1979 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2025 |