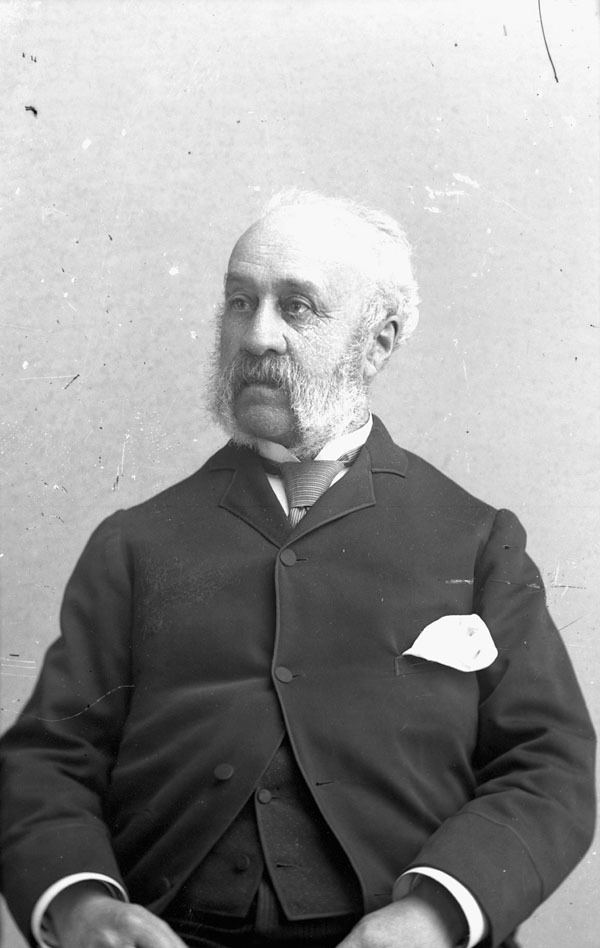

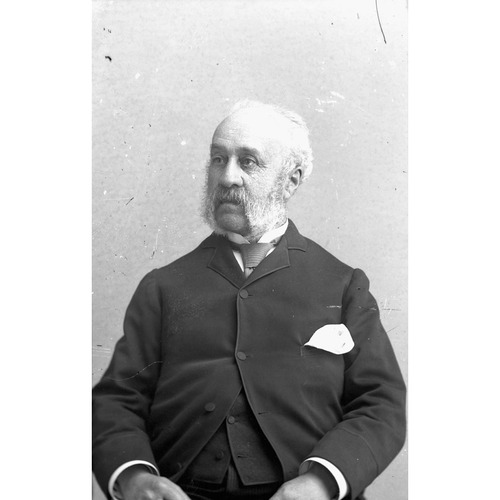

FULLER, THOMAS, architect and office holder; b. 8 March 1823 in Bath, England, son of Thomas Fuller, carriage-maker, and Mary Tiley; m. 1853 Caroline Anne Green of Bath, and they had one son and two daughters; d. 28 Sept. 1898 in Ottawa.

Thomas Fuller received his architectural training, at least in part, in the office of James Wilson of Bath. Wilson, young himself at the time, was thought something of a radical and is considered responsible, more than anyone else, for applying the revived Gothic mode, already popular for Anglican and Roman Catholic churches, to nonconformist places of worship. Wilson also specialized in the design of schools – important background for Fuller in his later designs for secular public complexes.

In 1845 Fuller received his first known commission, St John’s Cathedral (Anglican) in Antigua. The building, though structurally innovative, was considered old-fashioned for the mid 1840s, being rendered in a late Georgian version of the Italian baroque. The design was not well received in Britain, where progressives were becoming increasingly partial to the Gothic Revival.

Fuller probably remained for a time in the Caribbean, where he is said to have “carried out some ecclesiastical works in Jamaica and other islands of the Antilles.” He had, however, returned to England by 1847, when there is evidence of a partnership at Bath and/or Bristol with William Bruce Gingell, who had also apprenticed under Wilson. In that year, working in the Italianate style, Fuller and Gingell won the competition to design the prison at Plymouth. In the same year they had a commission to design Unitarian schools at Taunton. Between 1848 and 1851, when the partnership is presumed to have ended, they designed schools and public buildings at Stonehouse (1848), London (1848), and Llandovery, Wales. In addition, in 1850 the firm did some houses at Portishead.

By the late 1840s, despite the public-building designs in the Italianate style with which his name is connected, Fuller’s sympathies would seem to have lain at least equally with the progressive young Gothic Revivalists who followed Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin and were known as Ecclesiologists for their commitment to medieval purity in church design. Fuller may have assisted the brothers John Raphael and Joshua Arthur Brandon in preparing illustrations for their volumes on English medieval architecture, and he was definitely one of a group of younger architects who, at founding meetings of the Bristol Society of Architects, expressed impatience for stylistic change.

In or about 1851 Fuller formed a partnership with his former master, James Wilson. In the same year he “retired” from the Royal Institute of British Architects, having apparently been ejected for a professional misdemeanour of some sort. Once again, the work of Wilson and Fuller seems to have been chiefly of a public and institutional nature.

In 1855 the town hall of Bradford-on-Avon was built to the design of Fuller, now practising on his own. The building echoes the Italianate manner of the public buildings executed a few years earlier with Gingell but it also announces the bold High Victorian character for which Fuller became known in Canada. Apart from this and a police station in Bath, however, Fuller’s work of the later 1850s seems to have taken a decidedly ecclesiastical, and therefore Gothic, turn.

In 1857 Fuller left for the Canadas and by September had established himself in Toronto. The city was already the metropolis of Upper Canada, and architects, especially those of British origin such as William Thomas* and Frederic William Cumberland*, had found it a good place to set up shop. There were as yet no facilities for training architects in North America apart from the offices of practising professionals, and the provinces depended on the mother country to fill the need. Moreover, at this time architecture throughout North America was taking on a strongly British flavour. Even in the United States (usually more resistant to British than to French influence) a bold and forceful handling of form, modelled on the work of the British Victorian Gothic architects, was fashionable for churches, residences, and some types of public buildings. Because of its Anglo-Scots character, Toronto became a particular Mecca for English practitioners of the Victorian Gothic mode.

Fuller’s earliest Canadian work was thoroughly in keeping with his preference for medieval styles. It is possible that he worked with Cumberland and William George Storm on the building of University College in Toronto, and in 1858 he received a commission to design the Anglican church of St Stephen-in-the-Fields on College Street. In keeping with its suburban location, St Stephen’s (which was built at the expense of Colonel Robert Brittain Denison) was an elegant brick-and-stone version of a popular High Victorian Gothic type modelled on medieval parish churches such as St Michael’s, Longstanton, the Ecclesiologists’ approved model for small churches overseas. St Stephen’s was, however, burned in 1865 and rebuilt in its present enlarged form by Gundry and Langley.

In June 1858 Fuller joined the existing partnership of Robert C. Messer and Chilion Jones, civil engineers. Messer left the partnership in the summer of 1859, probably for Brazil. Jones remained Fuller’s partner until 1863. The firm’s specialty became the design of churches, almost all Anglican and of the same Gothic village-church type as St Stephen’s. The partners designed churches in several Upper Canadian communities: Stirling (1860–61), Lyn (1860), Almonte (1862–64), Westboro, outside Ottawa (begun 1865), and perhaps Simcoe (1860). While working in Ottawa, Fuller also designed St James, Hull (1866–67). In addition, though he was not entirely responsible for their design, St James, Perth (1853–61), and Holy Trinity, Hawkesbury (1859), reflect Fuller’s involvement. He also deserves ultimate credit for the important Ottawa church of St Alban the Martyr, Sandy Hill (1866–68). For all these churches Fuller’s deft, forceful handling of the Early English Gothic was highly appropriate. He is known to have designed only one non-Anglican church – St James (Presbyterian) in London, Upper Canada (1859–61). Here Fuller dressed out in his familiar Early English detail a central-plan building, reminiscent of the library of the Parliament Buildings, which he had just designed, and more suited to the demands of Protestant ritual than the conventional oblong form.

The most important commission of Fuller’s career was the design of the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa. Fuller and Jones’s design in civil Gothic, consisting of a pair of symmetrical pavilioned wings flanking a central tower, with a circular library at the rear that was modelled on a monastic chapter house or kitchen, was selected over 15 other entries in a competition held in the summer of 1859. Their alternative entry on identical floor plans but in the Italianate style was not premiated, and their entry in the competition to design the departmental blocks placed second, after that of Thomas Stent and Augustus Laver.

Fuller’s design for the Parliament Buildings was a great critical success and received wide publicity in Europe and America. It married recent developments in the Gothic Revival to French academic planning and incorporated the most advanced technological services (four types of heating systems, innovative water and ventilation systems, and electrical signal-bells), thereby answering the plea of noted critic John Ruskin for the application of medieval styles to contemporary building programs. The result – formal facing the city yet picturesquely asymmetrical toward the Ottawa River – was thought ideal to express the building’s ceremonial character and the wild northern scenery. Anthony Trollope, visiting Ottawa in 1861, wrote: “The glory of Ottawa will be – and, indeed, already is – the set of public buildings which is now being erected on the rock which guards as it were the town from the river. . . . I have no hesitation in risking my reputation for judgment in giving my warmest commendation to them as regards beauty of outline and truthful nobility of detail.”

Construction of the Parliament Buildings, however, proved extremely difficult. Rising costs, unforeseen delays, and suspicions of scandals in high places [see Samuel Keefer*; Thomas McGreevy] caused work to be halted in late 1861 and a commission of inquiry to be appointed. In its report, filed in 1863, the commission criticized the conduct of all the architects involved, though Fuller perhaps less than the others, but recommended that for the sake of continuity not all of them be dismissed. Thus, Fuller was appointed, as was Charles Baillairgé*, joint architect for the entire complex and was able to see his own design completed in its essentials by 1866, in time to house the legislature of the new dominion at its confederation the next summer. Unfortunately, only the library and the departmental blocks survived a fire in 1916.

Fuller’s career took other important strides in the 1860s. Besides the churches already named, Fuller (after 1863 working without a partner) had a number of commissions in hand, including a block of buildings on Elgin Street, Ottawa (1861); a house in the Gothic style, also in Ottawa (1864); and the synod house attached to St George’s Cathedral (Anglican), Kingston (1865). More important, though, in 1863, before Jones’s departure, the firm had entered and won a competition to design a new capitol for the state of New York in Albany. Undertaken in the midst of the economic boom created by the Civil War, the new capitol was intended to be the most ambitious public building on the continent, apart from the federal capitol itself, whose dome was just then being topped off. Unfortunately, all trace of Fuller and Jones’s prize-winning design of 1863 has vanished; in any case, no action was taken on it. Three years later a new competition was called, and in 1867 Fuller, working with the local firm of Nichols and Brown, had his design premiated. He was asked to work with Arthur Delavan Gilman, an adept in the French Second Empire style, and Augustus Laver, also a prizewinner, in developing a definitive scheme. With minor revisions, their combined design was built upon until 1875, when construction was stopped amid charges of graft and inefficiency. In March 1876 a reconstituted capitol commission recommended major changes to the capitol building. As a result Fuller was dismissed from the job. Though he seems to have been guilty, at most, of allowing too much of an unsavoury nature to go on under his nose, the incident was probably a considerable personal embarrassment, for he left Albany shortly afterwards and by 1881 was living in Glens Falls, N.Y.

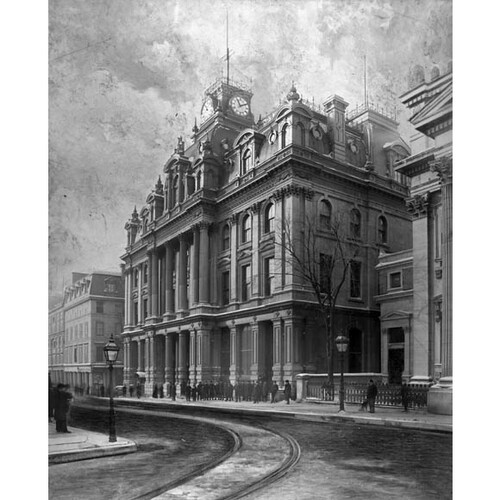

For a short time in the early 1870s, however, Fuller and Laver had found themselves in the forefront of the American architectural profession. For one thing, Fuller’s design for the capitol, though a little dated by the mid 1870s, was defended by many architects in what became a national cause célèbre. Moreover, in February 1871 Fuller and Laver won the competition to design the new city hall and lawcourts in San Francisco. This vast Second Empire complex was nearly 200 yards long and climaxed in a 300-foot tower/dome which was a stretched version of the capitol dome in Washington. Labelled by one critic “the most Westward effort in grand architecture the world has ever accomplished,” the San Francisco municipal buildings are symptomatic of the colossal scale of public building undertaken in the United States after the Civil War. Though Laver is usually credited with the design and he went to California to supervise construction, Fuller clearly had a hand in the project. In addition, the firm was called upon to compete for several of the most prominent public-building complexes of this expansionary post-war era. In association with Henry Augustus Sims of Philadelphia (formerly of Ottawa), Fuller and Laver had placed third in a competition in 1869 to design the towering Philadelphia city hall, and in 1871 they were one of only a few firms invited to submit designs for the prestigious Connecticut state capitol at Hartford. Clearly, the firm was in the vanguard of the ambitious, eclectic public-building activity of the era.

In October 1881 Fuller assumed the post of chief architect to the dominion of Canada left vacant by Thomas Seaton Scott’s retirement. Under Scott, who had served since 1871, most of the dominion’s many new public buildings had been designed in a mansarded Second Empire style, but by the early 1880s the Canadian government seems to have been seeking a more colourful and natural architectural image distinctive to Canada, yet in line with the fashionable neo-Romanesque manner of American architect Henry Hobson Richardson. The High Victorian Gothic of the Parliament Buildings presented a possible paradigm on which to base a national style. It was, therefore, particularly fortunate that Fuller should have presented himself for the post of chief architect at just this moment. Sir John A. Macdonald’s government was determined to raise the profile of the federal government in towns and cities across the dominion and Fuller’s international reputation and long experience with large public-building projects fitted him ideally to the task. The esteem in which he was held is further reflected by his election in 1882, shortly after his return to Canada, to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts.

One of his first undertakings, and probably the largest of his 15-year tenure as chief architect, was the design and construction of the Langevin Block, to face the Parliament Buildings across Wellington Street. Erected in 1883–89, it provided badly needed office space for the federal government since the departmental blocks flanking the Parliament Buildings were no longer sufficient. Fuller’s new building harmonized with the Gothic of the Parliament Buildings yet conformed to the Romanesque fashion in commercial and office architecture of the 1880s.

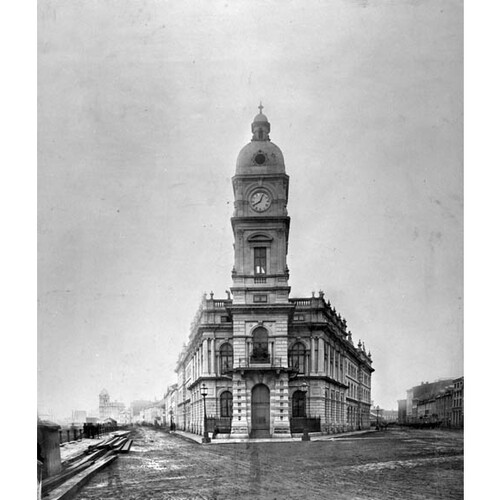

Most of the approximately 140 federal structures for which Fuller was responsible were, however, considerably smaller. About 80 were combined post office/custom-house structures, which were, especially in smaller towns, among the most distinguished buildings in their communities. Though Fuller himself was not responsible for every design, he lent a distinctive stylistic character to a building-type developed under Scott. In doing so he moulded a more or less consistent “Dominion image,” reminiscent of the Parliament Buildings yet in keeping with the more academic and subdued tastes of the 1880s and 1890s. Besides the many small structures, imposing post offices were built under Fuller in several cities: Hamilton (1882–87), Winnipeg (1884–87), Vancouver (1890–94), and Victoria (1894–98). He was also responsible for the design and construction of drill halls and armouries, prison buildings (notably at Saint-Vincent-de-Paul (Laval), Que.), customs warehouses, immigrant reception sheds, hospitals (particularly at Grosse-Île, Que.), and court-houses. And Fuller, or his chief assistant, David Ewart*, designed a Canadian exhibit building for the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. Finally, it is no small tribute to the respect accorded Fuller that he escaped the general purge of Public Works officials in the scandals that rocked the department in the early 1890s [see Sir Hector-Louis Langevin*].

The building types and styles developed for the federal government under Fuller, as well as his office organization, continued to influence the work of the chief architect’s branch until well into the 20th century. Through Ewart, assistant under both Scott and Fuller, and himself chief architect from 1897 to 1914, and Fuller’s son, Thomas William, who served as chief architect from 1927 to 1936, the high standard of federal design along dignified, traditional lines that Scott had initiated and Fuller had consolidated was maintained until the eve of World War II. Thus, besides a career as a designer of churches and public buildings in Britain, the West Indies, and North America, Fuller, beginning with his design for the Parliament Buildings in 1859, was a formative figure in shaping the architectural expression of Canada’s nationhood.

[The single most comprehensive treatment of Fuller’s life and work is found in the author’s “Dominion architecture: Fuller’s Canadian post offices, 1881–96” (ma thesis, 2v., Univ. of Toronto, 1978). c.a.t.]

NA, RG 11, D4, 3909–21; Cartographic and Architectural Arch. Division, RG 11M, Acc. 79003/29. American Architect and Building News (Boston), 62 (October–December 1898): 37. Builder (London), 75 (July–December 1898): 366. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1867–68, no.8 (report of the commissioner of public works); 1868–98 (annual reports of the Dept. of Public Works). Can., Prov. of, Dept. of Public Works, Documents relating to the construction of the parliamentary and departmental buildings at Ottawa (Quebec, 1862); Parl., Sessional papers, 1863, no.3. Canadian Architect and Builder (Toronto), 11 (1898): 168–69. Ottawa Citizen, 29 Sept. 1898. OttawaEvening Journal, 29 Sept. 1898. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. Margaret Archibald, By federal design: the chief architect’s branch of the Department of Public Works, 1881–1914 (Ottawa, 1983). B. F. L. Clarke, Anglican cathedrals outside the British Isles (London, 1958). John Coolidge, “Designing the Capitol: the roles of Fuller, Gilman, Richardson and Eidlitz,” N.Y., Temporary State Commission on the Restoration of the Capitol, Proceedings of the New York State Capitol Symposium (Albany, 1983), 21–27. Alan Gowans, Building Canada: an architectural history of Canadian life (Toronto, 1966); “The Canadian national style,” The shield of Achilles: aspects of Canada in the Victorian age, ed. W. L. Morton (Toronto and Montreal, 1968), 208–19. Ralph Greenhill et al., Ontario towns ([Ottawa, 1974]). W. E. Langsam, “The New York State Capitol at Albany: evolution of the design, 1866–1876” (ma thesis, Yale Univ., New Haven, Conn., 1968). Marion MacRae et al., Hallowed walls: church architecture of Upper Canada (Toronto and Vancouver, 1975). D. [R.] Owram, Building for Canadians: a history of the Department of Public Works, 1840–1960 ([Ottawa], 1979). Thomas Ritchie et al., Canada builds, 1867–1967 (Toronto, 1967). C. A. Thomas, “Thomas Fuller (1823–98) and changing attitudes to medievalism in nineteenth-century architecture,” Soc. for the Study of Architecture in Canada, Selected papers, vol.[III]: annual meeting, 1978, ed. Christina Cameron and Martin Segger (Ottawa, 1982), 103–47. A. H. Armstrong, “Profile of Parliament Hill,” Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, Journal (Toronto), 34 (1957): 327–31. W. E. Langsam, “Thomas Fuller and Augustus Laver: Victorian Neo-Baroque and Second Empire vs. Gothic Revival in North America,” Soc. of Architectural Historians, Journal (Philadelphia), 29 (1970): 270. D. [S.] Richardson, “Canadian architecture in the Victorian era: the spirit of the place,” Canadian Collector, 10 (1975), no.5: 20–29. C. [A.] Thomas, “Architectural image for the dominion: Scott, Fuller and the Stratford Post Office,” Journal of Canadian Art Hist. (Montreal), 3 (1976), nos.1–2: 83–94.

Cite This Article

Christopher Alexander Thomas, “FULLER, THOMAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 24, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fuller_thomas_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fuller_thomas_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Christopher Alexander Thomas |

| Title of Article: | FULLER, THOMAS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | December 24, 2024 |