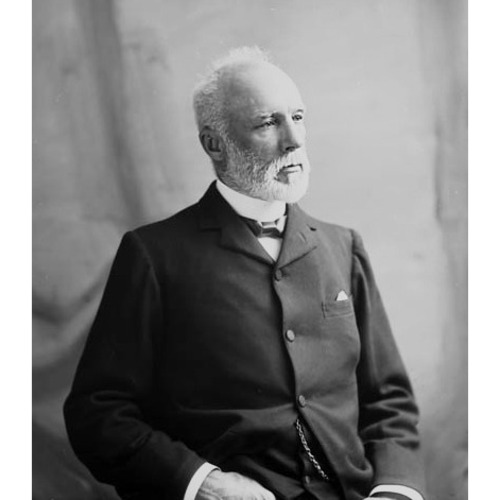

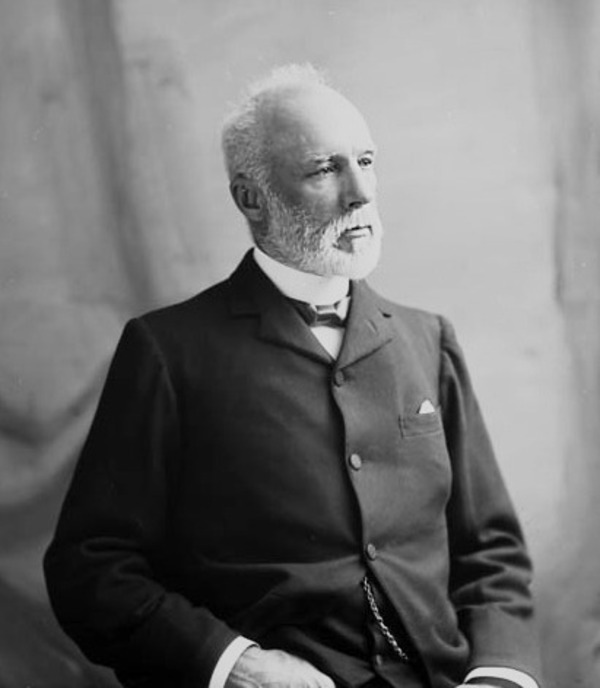

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

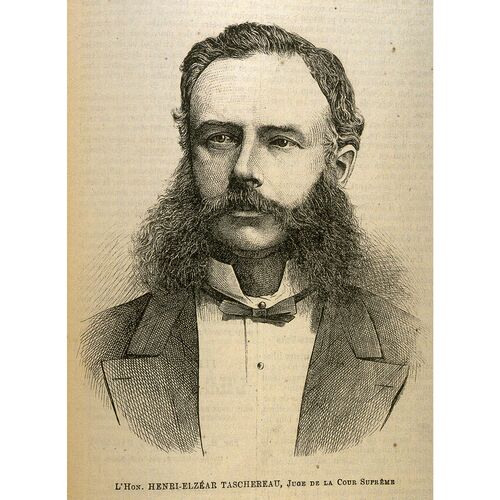

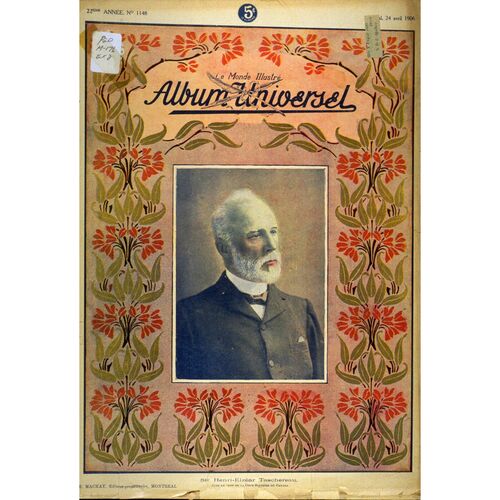

TASCHEREAU, Sir HENRI-ELZÉAR (baptized Elzéar-Henri), lawyer, politician, judge, and professor; b. 7 Oct. 1836 in Sainte-Marie-de-la-Nouvelle-Beauce (Sainte-Marie), Lower Canada, eldest son of Pierre-Elzéar Taschereau and Hémédine Dionne; grandson of Thomas-Pierre-Joseph Taschereau*; m. first 27 May 1857 in Vaudreuil, Lower Canada, Marie-Antoinette Harwood, daughter of Robert Unwin Harwood*, and they had seven children; m. secondly 22 March 1897 Marie-Louise Panet in Ottawa, and they had three children; d. there 14 April 1911.

At his father’s death Henri-Elzéar Taschereau inherited part of the seigneury of Sainte-Marie as well as the seigneurial manor. Since he was only eight years old, his mother administered the inheritance until he attained his majority. He received a classical education at the Petit Séminaire de Québec, which he attended from 1847 to 1853, and he studied briefly at the Université Laval. After being called to the bar of Lower Canada in October 1857, he practised law in Quebec City, first in the firm of a relative, Jean-Thomas Taschereau*, and from 1863 with Jean Blanchet.

Taschereau was elected to the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada in July 1861 and sat as a Conservative for the riding of Beauce. He was an outspoken supporter of the plan for confederation proposed by John A. Macdonald* and George-Étienne Cartier*, but at the last moment voted against this scheme in accordance with what he perceived to be his constituents’ interests. His electors voted him out of office in 1867, choosing a Protestant Liberal, Christian Henry Pozer*, for both the federal and the provincial ridings. Taschereau’s defeat ended the many years of political influence which his family had had in the region.

Taschereau was appointed clerk of the peace for the district of Quebec in December 1868, but resigned shortly afterwards to practise law in his home town. In January 1871 he was appointed a judge of the Superior Court for the districts of Saguenay and Chicoutimi and in 1873 he was transferred to the district of Kamouraska. There, during his “moments of leisure,” as he put it, he prepared an annotated edition of the province’s Code of Civil Procedure and an annotated consolidation of Canadian criminal law. The second work was the first of its kind; it would be re-edited twice and published under slightly different titles. Obliged by his career to leave his estate in Sainte-Marie, Taschereau decided to part with it, first renting it for some time and then selling it in 1874.

In October 1878 Taschereau was appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada, where he took the place of his relative Jean-Thomas Taschereau, who retired. Various distinctions were conferred on him during his time on this bench. He received an honorary lld from the Université Laval in 1890 and another from the College of Ottawa in 1893. A chair in law was created for him at Ottawa the same year and in 1894 he succeeded Sir John Sparrow David Thompson* as dean. The faculty of law folded in 1896, but Taschereau would continue to serve as an examiner for the college until 1910.

In November 1902 Taschereau was appointed chief justice of the Supreme Court, and thus became the first French Canadian to hold the position. Earlier in the year he had been created a knight bachelor. Taschereau’s judicial career was crowned by his elevation to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in 1904 and by his service as administrator of Canada from 21 November to 9 December that year, following the departure of Governor General Lord Minto [Elliot]. He retired from the Supreme Court in 1906 but continued to attend the sittings of the Judicial Committee, and was thinking of attending the coronation of King George V when his health worsened. He died in the spring of 1911.

Taschereau had had a roving spirit. During his years in Ottawa he often had to be called back from countries such as India, France, or the United States to sit on the bench. The same restlessness that drove him to traverse the globe in search of wisdom and experience led him to criss-cross jurisdictional and historical boundaries in search of persuasive authorities for his legal judgements. Thus, he rarely ever rested his decisions in the civil law of Quebec on the express provisions of the province’s Civil Code. He was always lifting the veil of codification, examining the arcane and exotic sources on which the code was supposedly based, and pointing out what he saw to be problems with the codification commission’s reasoning or use of sources [see René-Édouard Caron*], as well as putting forward his own solutions.

Another hallmark of Taschereau’s judgements was that he frequently turned to common law for guidance in resolving cases in civil law. He was equally accustomed to turning to civil law for possible solutions to problems in common law. In this way he sought to keep a dialogue going between Canada’s two great legal traditions. Being equally at home in both, he seems to have had no conception of any law as being foreign. Such legal cosmopolitanism was actually quite common among the legal élite of the mid 19th century, but by 1900 it had been largely supplanted by the ideology of legal positivism. This development alienated Taschereau, and there is a marked decline in the dialogical nature of his judgements towards the end of his judicial career.

Sir Henri-Elzéar Taschereau compiled Le Code de procédure civile du Bas-Canada . . . (Québec, 1876). He is also the compiler of The Criminal Law Consolidation and Amendment acts of 1869 . . . (2v., Montreal, 1874–75), and its second and third editions, which appeared as The criminal statute law of the Dominion of Canada, relating to indictable offences . . . as revised in 1886 . . . (Toronto, 1888) and The Criminal Code of the Dominion of Canada, as amended in 1893 . . . (Toronto, 1893).

ANQ-M, CE1-50, 27 mai 1857. ANQ-Q, CE6-24, 12 oct. 1836. AO, RG 80-5-0-243, no.3584. ASQ, Fichier des anciens. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). J.-G. Descôteaux, Faculty of law, University of Ottawa, 1953–1978 (Ottawa, 1979). I.-J. Deslauriers, La Cour supérieure du Quebec et ses juges, 1849–1er janvier 1980 (Québec, 1980). DPQ. David Howes, “Dialogical jurisprudence,” in Canadian perspectives on law & society: issues in legal history, ed. W. W. Pue and Barry Wright (Ottawa, 1988), 71–90; “From polyjurality to monojurality: the transformation of Quebec law, 1875–1929,” McGill Law Journal (Montreal), 32 (1986–87): 523–58. “Parliamentary debates” (Canadian Library Assoc. mfm. of the debates of the legislature of the Province of Canada and the parliament of Canada, 1846–74), 10 March 1865. J.-Y. Pelletier, Nos magistrats (Ottawa, 1989). Honorius Provost, Sainte-Marie de la Nouvelle-Beauce; histoire civile (Québec, 1970). Univ. Laval, Annuaire, 1858/59, 1891/92.

Cite This Article

David Howes, “TASCHEREAU, Sir HENRI-ELZÉAR (baptized Elzéar-Henri),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 15, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/taschereau_henri_elzear_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/taschereau_henri_elzear_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Howes |

| Title of Article: | TASCHEREAU, Sir HENRI-ELZÉAR (baptized Elzéar-Henri) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 15, 2024 |