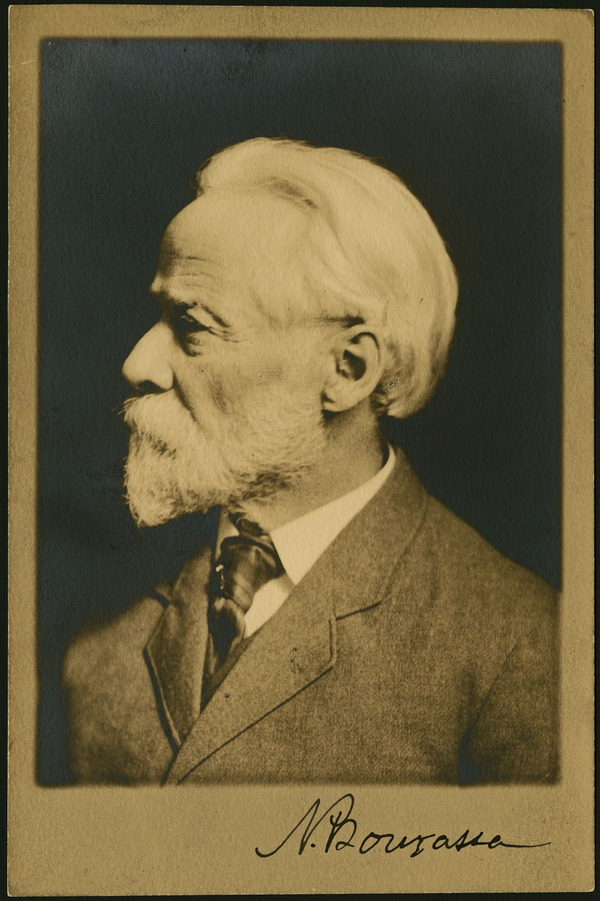

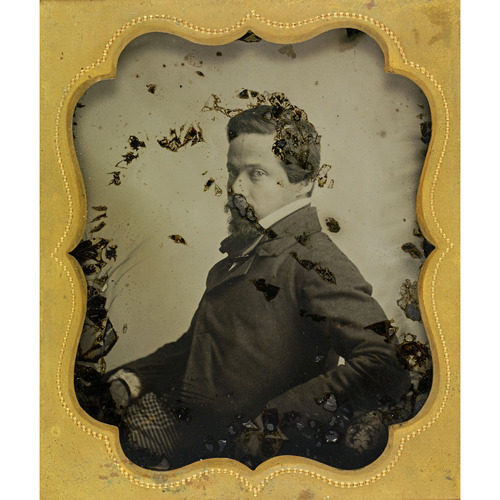

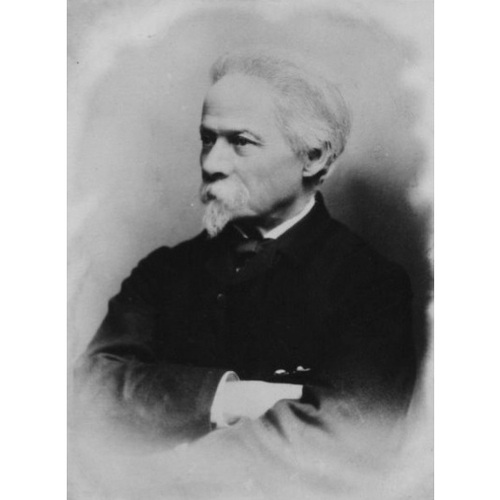

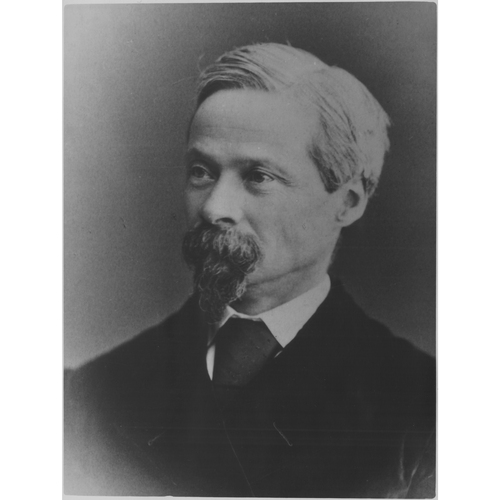

BOURASSA, NAPOLÉON, painter, author, teacher, sculptor, and architect; b. 21 Oct. 1827 in L’Acadie, Lower Canada, youngest child of François Bourassa, a farmer, and Geneviève Patenaude; m. 17 Sept. 1857 Azélie Papineau, daughter of Louis-Joseph Papineau* and Julie Bruneau, in Montebello, Lower Canada; d. 27 Aug. 1916 in Lachenaie, Que., and was buried 31 August in Montebello.

Napoléon Bourassa had an unusually long schooling for his time. The period he spent with the Sulpicians at the Petit Séminaire de Montréal, from 1837 to 1848, enabled him to develop a rare literary talent, which would shine brilliantly in the years ahead. He was articled to Norbert Dumas, a lawyer, and then began studying art. For 18 months he took private lessons at the studio of the painter Théophile Hamel*, and from July 1852 to November 1855 he pursued his artistic training in Europe, staying for more than three years in Florence and Rome and for some time in France. Michelangelo, Raphael, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and Hippolyte Flandrin were the artists for whom he would later express the highest regard. During his five years as an art student, Bourassa never mentioned courses in sculpture or architecture, yet he would practise these disciplines even past his 77th birthday.

At the beginning of his career Bourassa worked mainly as a critic, author, and teacher. He wrote numerous articles on ancient art and the art of his own era. His aesthetics, which were strongly influenced by Victor Cousin’s Du vrai, du beau et du bien (Paris, 1853), rested on three fundamental ideas. Drawing on many historical examples, Bourassa demonstrated that religion has always been the main source of inspiration for artists and the main object of their endeavours. An eclectic thinker, he then looked objectively at Canada and concluded that it could not hope to create a new civilization and that therefore artists must choose from the great Christian masters the most interesting forms and techniques for producing works useful to the country. Lastly, he made an appeal to the state, which alone could afford to commission public works of art and had the spiritual nobility to concern itself with great themes worthy of being preserved for future generations.

Given the paucity of orders from state and religious bodies throughout the period in which he was active, Bourassa reluctantly concentrated at first on portrait painting. He also devoted much energy to promoting instruction in the visual arts. At least three large institutions in Montreal had him teach their students: the École Normale Jacques-Cartier in 1861–62 and the Collège Sainte-Marie and the Institut Canadien-Français des Arts et Métiers in 1865. The respect Bourassa enjoyed among his peers is shown by the fact that in 1869 some of his works were chosen by Joseph Chabert* to give students an example of a “Canadian authority.” In 1877 the provincial government would ask him to study art education in Europe and bring back pedagogical material. These activities, and public lectures such as “De l’utilité des cours publics de dessin” (1865) and “L’enseignement de l’art au Canada” (1877), contributed significantly to the promotion of art among the general population.

After his marriage had brought him into the famous Papineau-Dessaulles family, Bourassa wrote a novel based on the poignant theme of the separation of two young lovers during the British deportation of the Acadians in 1755. Jacques et Marie; souvenir d’un peuple dispersé, which literary experts find conventional, appeared first in the Revue canadienne from July 1865 to August 1866, before being published in 1866 by Eusèbe Senécal*.

Despite the importance of Bourassa’s other writings, his greatest claim to literary fame is his correspondence. These intimate letters deal mainly with domestic life, feelings, meetings, births, and deaths. He recounts in masterly fashion the lives of the Papineau family, the family of Georges-Casimir Dessaulles, and his own family, which included Henri Bourassa*. This correspondence is an essential source for studying his career and understanding his personality and his social milieu, whether at Fall River, Mass., Montebello, Montreal, or Saint-Hyacinthe. The 322 letters published through the efforts of his daughter Adine are not uniformly the most important ones and they are often hard to understand because entire passages and many names have been deleted, including those of the persons to whom they are addressed. Still not well known as a letter writer, Bourassa deserves careful study based on a critical edition of all his letters.

Although his real passion as a painter was for great themes, Bourassa was to produce admirable portraits, even when it went against the grain. “I do not like trivial genres,” he observed; “they do not suit me, I would not have much success with them and I think it is a waste of one’s life to spend time on them. And doing ecclesiastical or historical canvases for mustard merchants or worthy curés who understand nothing about painting is not very exciting!” His austere portraits of church and state dignitaries place him in the tradition of his teacher Hamel – Bourassa made no attempt whatever to innovate in a genre he found distasteful. On the other hand, his pencil sketches show admirable sensitivity and spontaneity (Adine Bourassa, Musée du Québec), and many other painted portraits achieve the same perfection, especially those of his own family (Louis-Joseph Papineau, Henri et Adine Bourassa, Autoportrait avec sa femme, Musée du Québec).

In 1869, when he was 42, Bourassa’s wife died, leaving him with five children. Apart from portraits of priests, a few friends, and his close relatives, he had not had the opportunity to complete any important works. However, he had been chosen in 1867 to send a painting to Paris for the universal exposition. It was a study for a huge work that would finally be unveiled, at the Musée du Québec, more than 60 years after his death: Apothéose de Christophe Colomb.

Not attracted to the unglamorous work of painting at the easel, and always eager to promote teaching of the arts, Bourassa turned to architecture and the decoration of church interiors in hopes that he would at last find the right setting for his talents. The plans he drew up for the churches in Saint-Jérome and Saint-Jovite, for the chapel of the Sisters of the Sacred Heart in Montreal (on Rue Sainte-Catherine), for the presbytery of Sainte-Anne in Fall River, for a Swiss project in Saint-Hyacinthe (five plans), for theatres and concert halls, and for the family vault in the Montebello cemetery, deserve passing mention. But eight major projects, carried out between 1870 and about 1904 constitute his most outstanding work: the decoration for the chapel of the Asile Nazareth (1870); Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes chapel in Montreal (1872–80); a decorating project for the church in Saint-Hugues (1872); a mural for the church in Saint-Ours (undated sketches); drawings from the life of St Hyacinth (1885–92); the façade of the Dominican convent in Saint-Hyacinthe (1892); the church in Montebello (1895); and the church of Sainte-Anne in Fall River (1892–1904).

Montrealers can still admire Bourassa’s achievements in Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes chapel, which were on a huge scale. He himself drew up the plans and oversaw the architectural work and murals that are divided into 30 main scenes framed by secondary motifs. Student artists collaborating with him (indeed in some cases living in a room added on to his studio) undertook some of the drawing and carried out tasks that became increasingly complex as the project advanced. Bourassa kept for himself the designing of the principal scenes, added the colour, handed the sketches back to the students, and supervised their work on a daily basis. Some of them, including François-Édouard Meloche and Louis-Philippe Hébert, would become artists themselves. These two apprentices subsequently contributed to the development of the arts in Quebec; Hébert, in particular, created single-handed most of the large bronze monuments in the province up to the turn of the century. Olindo Gratton*, who produced more than 300 pieces between 1877 and 1939, worked with Bourassa and Hébert when they set up a school for sculptors; he was also in Fall River in 1905.

Bourassa’s greatest merit as a sculptor will undoubtedly remain the awakening of Hébert’s gifts. Although he himself did not produce many works of sculpture (Buste de Louis-Joseph Papineau, in the chapel of Louis-Joseph Papineau’s manor-house at Montebello, is one of the few), he felt he had the talent necessary for great tasks. Replying in 1883 to Siméon Le Sage*, who had consulted him about decorating the new legislative building at Quebec [see Eugène-Étienne Taché], Bourassa made a long, highly technical report on the subject and indicated his readiness to undertake “all the exterior and interior decoration, [with] responsibility for and control of the entire work.” He added that he would bring Hébert in as his partner on the statuary, but Hébert himself was to get this contract.

In 1885 Bourassa took on a vast project: renovating the cathedral in Saint-Hyacinthe, altering the interior, and doing all the drawings for the décor. What with the enormous cost of reinforcing the structure and certain differences of opinion between members of the clergy responsible for the undertaking, the work came to a halt in 1892. It is thought that Bourassa himself only did wash drawings of St Hyacinth’s life, splendid illustrations more than three feet high which are among the most beautiful pieces in the Musée du Québec.

Between the ages of 68 and 77 Bourassa built two important churches, one in Montebello and the other the large church of Sainte-Anne in Fall River. Construction in Montebello was approved on 14 Dec. 1893 and entrusted to him. On 30 Jan. 1895 he received $758 for the plans, at least 15 of which are held at the Musée du Québec. The cornerstone was laid on 13 May 1895 and work proceeded briskly with the help of his assistant Meloche. Officially completed on 24 March 1896, the church was consecrated that day. It was a cruciform structure 136 feet long and 120 feet wide at the transepts, with a main nave 50 feet wide and 44 feet high at the centre of the arch. The sanctuary was set at the centre, but this arrangement would be modified in 1932 when the length of the building was increased by half. The removal of the baldachin in 1951 would radically alter the interior appearance.

The church at Fall River, much larger and probably inspired by the cathedral in Marseilles, France, is surprising because of its vast dimensions and the brightness of its interior decoration. It was built by the Dominican fathers to serve the French-speaking community that had recently immigrated to New England. Of the approximately 54,000 inhabitants of Fall River, some 11,000 had come from Quebec and worked for the most part in the textile mills. Throughout the duration of the project, people of French Canadian origin were called upon to contribute in every way possible: pew rental, collections at home, retreats, pilgrimages, parties, Sunday offerings, collections from children, casual offerings, and above all the famous bazaars, which were ridiculed by Bourassa in his letters and were described at great length in the local newspapers, especially L’Indépendant. The land was bought in May 1892 for $19,000 and the plans – 25 of which are held at the Musée du Québec – were completed within a year by Bourassa, and made public at a year-end meeting in the parish school, as L’Indépendant reported on 22 June 1893. However, construction was not authorized by Bishop Matthew Harkins of Providence, R.I., until 10 Jan. 1902. Bourassa signed the contract on 17 February and on 14 July the first stone was set in place for this church of white Vermont marble, which would be 277 feet long by 122 wide, with steeples 160 feet high. After the last stone was laid in June 1904, Bourassa seldom visited the building site. In August 1905 his pupil Meloche decorated the Chapelle Notre-Dame and the Chapelle du Rosaire. Bourassa did not attend the dedication of the building, which took place on 4 July 1906.

Along with this church, the colossal painting entitled Apothéose de Christophe Colomb may be considered Bourassa’s final achievement. Until the age of 86 he struggled in vain to finish the latter piece, which was a masterful embodiment of the artistic principles he had set forth at the beginning of his career. A comparison of his Vigilance, Strength, and Constancy with the figures done by Raphael and Giulio Romano in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican makes manifest Bourassa’s unwavering fidelity to the great masters of religious painting.

It is now known that each of Bourassa’s projects was thought out and prepared in minute detail. If this dimension of his activity is not taken into account, the true worth of the gigantic task he set himself cannot be appreciated. His work developed like a spiral, building on the experience of the previous stage and constantly broadening out as time went on: first, painting at the easel (including portraits), literature (historical novel and art criticism), and traditional teaching; then murals and sculpture; finally, architecture, incorporating teaching, sculpture, drawing, religious murals, and historical painting.

A critical edition of Bourassa’s entire literary output will add to knowledge not only of his life but of the lives of other great Quebec families. His pictorial work has not yet been catalogued. No studies have been done of the churches associated with Bourassa’s name except for Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes, which was incompletely examined since the plans were not used. The 172 architectural plans discovered in the archives division of the Université Laval in 1976 and presented to the Musée du Québec in 1981 are an example of the available sources. Apart from obvious artistic value, these works (some in very finished state), reveal the ambitions, culture, and tastes of the clergy. The church as a catalyst of social forces, when under construction, could be readily studied in the case of Fall River, given the importance of the undertaking for the French-speaking population and the abundance of documents. The records in the parish archives of Montebello and Sainte-Anne, on which this biography is partly based, have not yet been published. The role of the Papineau–Dessaulles family in Bourassa’s career deserves thorough examination, as do his Oblate and Dominican connections. No study has been done, either, of Bourassa as administrator for certain geographical portions of the seigneury of Petite-Nation and for the family fortune. His influence on the art and culture of his time may become clear when his ideas for sculptures and his activities as a critic, teacher and foreman, painter, and architect are better known.

Napoléon Bourassa flourished at a time when Quebec society was not yet in a position to launch great cultural projects or in possession of the infrastructure required to support artistic life. He was active in every field where he could encourage development of the visual arts. As a lecturer, a contributor to the Revue canadienne and a member of its board of directors from 1864 to 1868, the president of art associations, and one of the 25 artists who in 1880 founded what would become the National Gallery of Canada [see Lucius Richard O’Brien*; John George Edward Henry Douglas Sutherland Campbell], he participated in most of the artistic ventures in the second half of the 19th century. The rapid evolution of cultural life in Quebec during the 20th century has given the false impression that Bourassa was an ossified and reactionary artist. He was, rather, an extremely important agent within a monolithic society suddenly caught up in complex and powerful evolutionary forces.

[The author has reconstructed and analysed Napoléon Bourassa’s career and work on the basis of his artistic legacy (works of architecture, sculpture, and interior design, paintings and drawings, and materials from his studio) as well as from manuscripts preserved in numerous archives in Canada and the United States, primary printed sources (contemporary journals and newspapers), secondary studies devoted to Bourassa or in which he is mentioned, and reference works. A comprehensive listing of these sources appears in the author’s unpublished 28-page article, “Napoléon Bourassa: bibliographie” (1993), a copy of which is available at the DCB. r.v.]

Cite This Article

Raymond Vézina, “BOURASSA, NAPOLÉON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 4, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourassa_napoleon_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourassa_napoleon_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Raymond Vézina |

| Title of Article: | BOURASSA, NAPOLÉON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | January 4, 2025 |