Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

DEMASDUWIT (Shendoreth, Waunathoake, Mary March), one of the last of the Beothuks; b. c. 1796; m. Nonosbawsut, and they had one child, who died as an infant in 1819; d. 8 Jan. 1820 at Bay of Exploits, Nfld.

In September 1818 a small band of Beothuk Indians, not for the first time, pilfered the salmon boat and the equipment and gear of John Peyton Jr at the mouth of the Exploits River on the northeast coast of Newfoundland. The governor, Vice-Admiral Sir Charles Hamilton*, in response to a request from the injured settlers and others, authorized the dispatch of a party to recover the stolen property. The expedition was also intended to act, with unperceived incongruity, on behalf of the British and Newfoundland authorities in still another of the efforts made over a long period to establish friendly relations with the dwindling survivors of the Beothuk people. Its goal was Red Indian Lake, the principal winter quarters of the Beothuks, which had already been the scene of officially sponsored searches by the naval officers John Cartwright in 1768 and David Buchan* in the winter of 1810–11. This expedition, like its predecessors, was unsuccessful; indeed it was to prove a tragic and perhaps decisive failure.

Led by John Peyton and his father John*, a small band of heavily armed furriers set out on 1 March 1819 up the frozen Exploits into the interior, arriving unobserved at the shores of Red Indian Lake on the 5th. As they closed in on a group of three wigwams, a dozen or more Indians fled into the woods or across the expanse of ice. One of the latter groups, labouring in the snow and pursued by John Peyton Jr, threw herself down, exposing her breasts in a gesture of supplication, and was captured; this was Demasduwit. As she was dragged back to the main party of settlers, one of the Indians, later identified as her husband Nonosbawsut, followed at a distance by another, approached the group brandishing a club. An elaborate but mutually incomprehensible exchange of words followed, though the intent of the Indian, release of the woman, must have been obvious. A desperate scuffle followed between Nonosbawsut and the furriers; in the mêlée one of the furriers stabbed Nonosbawsut with a bayonet, shots were fired, and he fell mortally wounded. It is a plausible conjecture that his death removed the most experienced and decisive leader of the surviving Beothuks, sealed the enmity between the two competing peoples, and hastened the disintegration of the remnants of the tribe. Peyton’s party examined the encampment, identified the stolen property (including kettles, knives, axes, fish-hooks, fishing-lines, and nets), and returned to the coast, their captive several times attempting to escape.

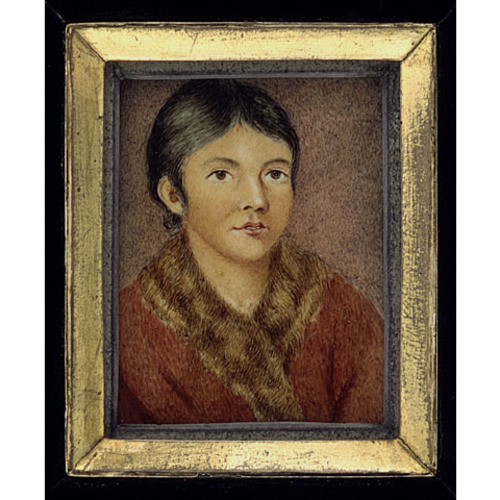

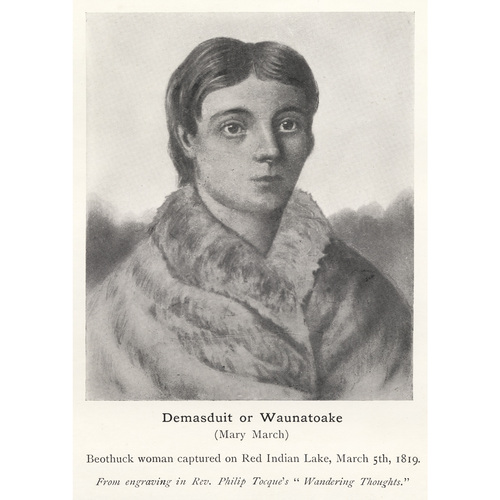

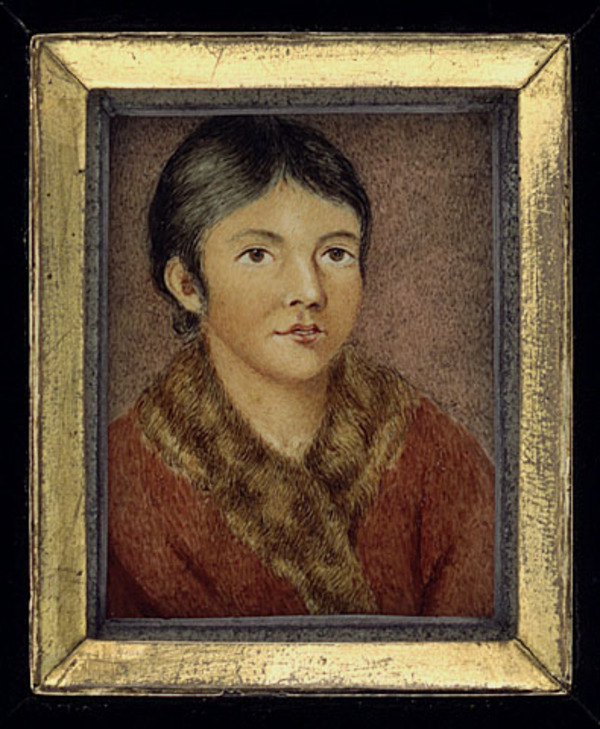

Taken to Twillingate, Demasduwit was placed in the care of the Anglican missionary John Leigh*; and when spring navigation opened on the coast Leigh and Peyton Jr brought her to St John’s by schooner. There she remained for several months, a familiar figure in the capital (where she was known as Mary March) and a visitor to the governor’s residence, where Lady Hamilton executed a well-known portrait. Gentle, intelligent, and tractable, Demasduwit is said to have evinced particular attachment to her captor, Peyton Jr. He and other members of the party were absolved of the killing of her husband by a grand jury at St John’s on 25 May, which found that there was “no malice on the part of Peyton’s Party to get possession of any of [the Indians] by such violence as would occasion Bloodshed.”

Anxious to return the captive to her people, and in accordance with a proposal to this effect from a group of influential inhabitants of both St John’s and Notre Dame Bay, who raised a subscription towards the cost, the governor had her placed aboard a vessel and sent northward on 3 June 1819, Leigh boarding at Trinity. There followed, between 18 June and 14 July, a number of attempts to place her in the hands of Beothuk tribesmen known to be at their summer stations on the coast and river estuaries. All proved unsuccessful, however, and Demasduwit was again given into the care of Leigh at Fogo and Twillingate, the occasion permitting him to continue the compilation of a vocabulary of the Beothuk language from information derived from her. In September 1819, Buchan arrived in Notre Dame Bay aboard the Grasshopper with instructions to take the captive inland during the winter freeze-up when travel would be easier; and in late November Demasduwit was brought aboard the vessel to be in readiness for the execution of the new plan. But, her health now greatly deteriorated, she succumbed to tuberculosis at Ship Cove, near Botwood, on 8 Jan. 1820.

On his own authority, Buchan decided to salvage what he could of the situation and on 21 January, accompanied by John Peyton Jr, he led a party of 50 marines and some furriers up the Exploits to return Demasduwit’s body to Red Indian Lake. Covertly watched by the Beothuks (including Demasduwit’s niece Shawnandithit*), the party arrived at the empty winter encampment on 9 February. There the body, carefully arrayed, was left with gifts in one of the wigwams, and the expedition returned by a longer route to the coast. Shawnandithit later described to William Eppes Cormack* how the body of Demasduwit was placed with that of Nonosbawsut in a sepulchre by her people. In its final resting-place it was seen by Cormack in November 1828 when, on the last melancholy expedition in search of the Beothuks, he reached the unfrozen expanse of Red Indian Lake, the shores of which had once been the inland home of the unfortunate tribe, and found them abandoned and silent.

[The principal contemporary sources, the originals of many of which are preserved in the PANL, are printed in J. P. Howley, The Beothucks or Red Indians: the aboriginal inhabitants of Newfoundland (Cambridge, Eng., 1915; repr. Toronto, 1974, and New York, 1979); no significant additional sources concerning Demasduwit have since been found. Howley was also able to draw upon a number of eye-witnesses: John Peyton Jr. (pp.91–94), John Leigh (127–29), and a Mr Curtis (179–80). Shawnandithit’s information recorded by Cormack is given at pp.227–28.

Near-contemporary accounts and information are given by the following: L. A. Anspach, A history of the island of Newfoundland . . . (London, 1819); R. H. Bonnycastle, Newfoundland in 1842: a sequel to “The Canadas in 1841” (2v., London, 1842); Charles Pedley, The history of Newfoundland from the earliest times to the year 1860 (London, 1863); and Philip Tocque, Wandering thoughts; or, solitary hours (London, 1846).

In secondary sources, recent studies include: John Hewson, Beothuk vocabularies (St John’s, 1978), 33–55; F. W. Rowe, Extinction: the Beothucks of Newfoundland (Toronto, 1977), 61–70; Peter Such, Vanished peoples: the archaic Dorset & Beothuk people of Newfoundland (Toronto, 1978); the same author’s novel, Riverrun (Toronto, 1973); and J. A. Tuck, Newfoundland and Labrador prehistory (Ottawa, 1976), 62–76. For discussions on the problems regarding portraits see Ingeborg Marshall, “The miniature portrait of Mary March,” Newfoundland Quarterly, 73 (1977), no.3: 4–7; and Christian Hardy and Ingeborg Marshall, “A new portrait of Mary March,” 76 (1980), no.1: 25–28. g.m.s.]

Cite This Article

G. M. Story, “DEMASDUWIT (Shendoreth, Waunathoake, Mary March),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 5, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/demasduwit_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/demasduwit_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | G. M. Story |

| Title of Article: | DEMASDUWIT (Shendoreth, Waunathoake, Mary March) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | April 5, 2025 |