As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

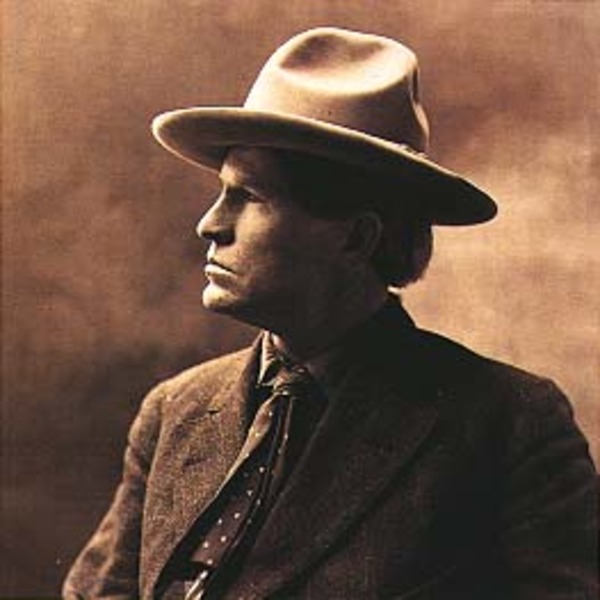

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

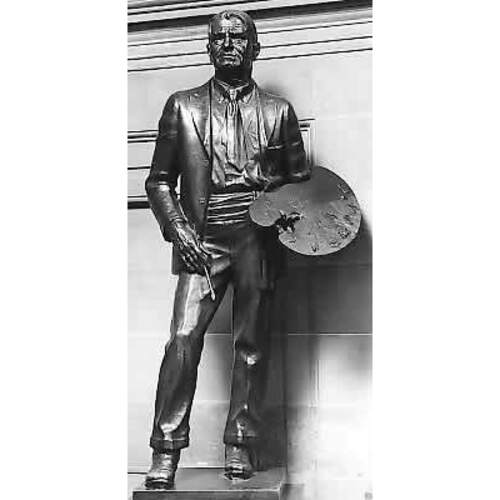

RUSSELL, CHARLES MARION, artist; b. 19 March 1864 in St Louis, Mo., son of Charles Silas Russell and Mary Elizabeth Mead; m. 9 Sept. 1896 Nancy Cooper (d. 1940) in Cascade, Mont., and they had one son; d. 24 Oct. 1926 in Great Falls, Mont.

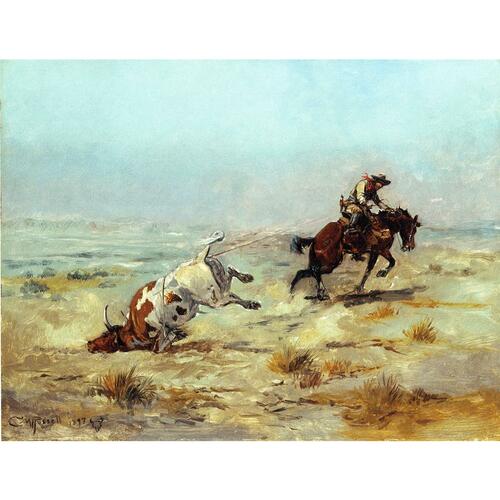

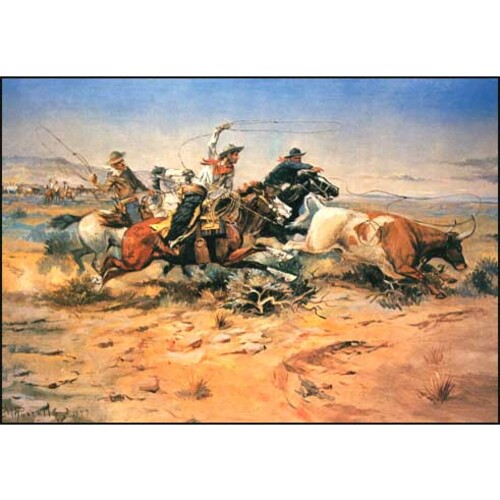

Charlie Russell’s father was a partner in a brick manufacturing firm and the family was socially prominent. From an early age, the boy, who struggled in school, dreamed of going west to follow in the footsteps of his grandmother’s brothers Charles and William Bent, pioneer western fur traders. In 1880, just before his 16th birthday, his parents let him accompany a sheepman of their acquaintance to Montana Territory. After living with a professional meat hunter, “Kid” Russell in 1882 hired on as night herder on a trail drive to the Judith Basin in central Montana. Over the next 11 years (apart from 1888, when he summered in what is now Alberta), he wrangled horses and cattle during the spring and fall round-ups and gained a local reputation as an amusing story-teller with a knack for drawing the life around him. His 1887 watercolour Waiting for a chinook, showing a starving cow surrounded by wolves, summed up a devastating winter on the plains and brought him widespread recognition.

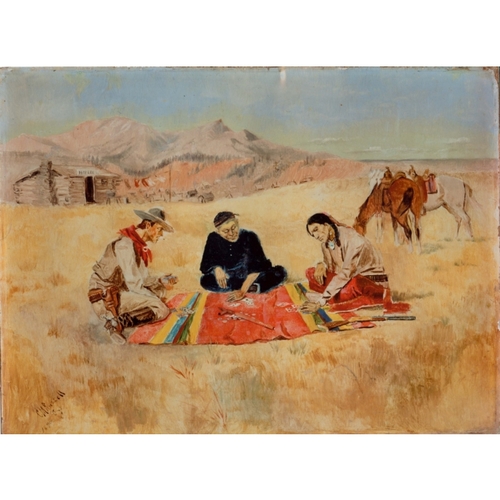

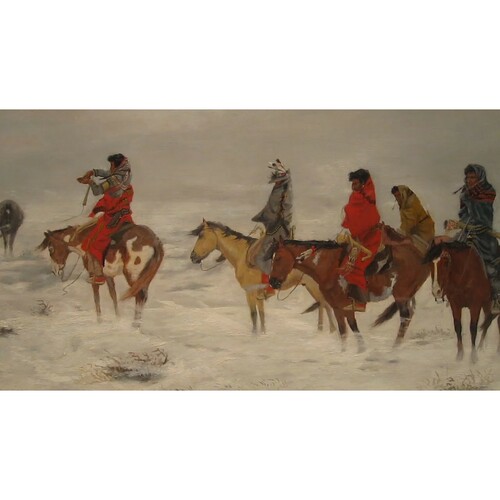

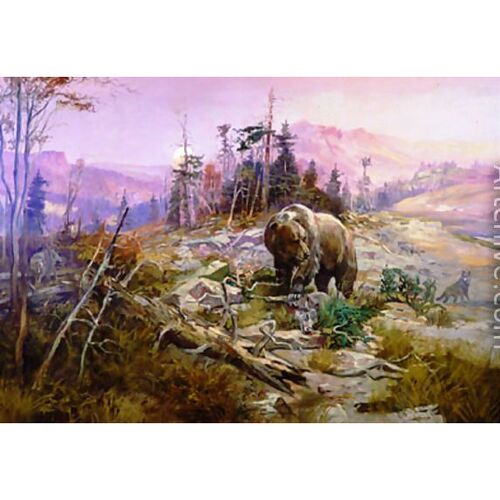

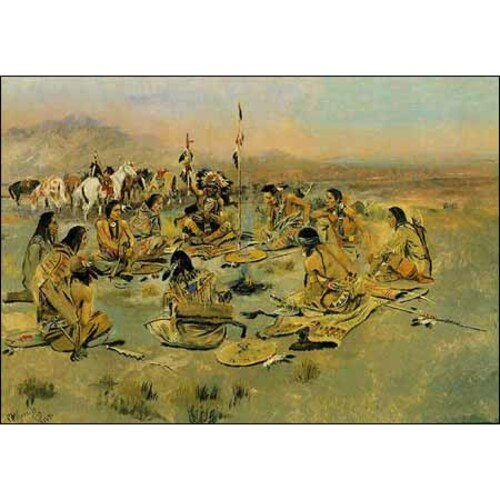

His first visit to Canada was a key event in Russell’s life. He rode north from Helena, Mont., with two friends in late May 1888. A job awaited one of them, Philip A. Weinard, who was to take up a position at a ranch southwest of Calgary. But Russell and his other companion, having missed the spring round-up, fished, hunted, and loafed the summer away on a ranch owned by Charles D. M. Blunt. Russell did a few paintings with supplies given him by Blunt and took the opportunity to acquaint himself with the native peoples of the area – Stoney, Sarcee, Blackfoot, Blood, and Peigan. Impressionable and eager to learn, he picked up the rudiments of sign language and absorbed tales of valour from times past. They left a permanent impression on his art, adding to his understanding of cowboy life an abiding interest in Plains Indian culture. Russell returned to Helena in September, leaving behind some sketches, a finished painting of a bear, and, most impressively, an ambitious oil that he gave to Blunt, Canadian mounted police bringing in Red Indian prisoners, recording an incident witnessed on the ride north in May. In later paintings and drawings he would honour the mounted police as symbols of justice on the Canadian frontier, a notable subject for an artist who ignored the United States army’s role in “winning the west” and sympathized with the Indians in their resistance to white advance.

After his return to Montana, Russell went back to night herding. But in 1893, convinced that the glory days of the open-range cattle industry were over, he turned to art for a living, settling in the town of Cascade, between Helena and Great Falls. There in 1895 he met Nancy (“Mame”) Cooper, a 17-year-old whom he married the following year. She proved to have a head for business and drive enough for both of them. They moved to Great Falls in 1897 and together made an impulsive trip north in 1903. Eager to see the last frontier of the northern gold rushes, they set out by train for “Fort Edmonton,” only to discover a modern city. Russell was able to sketch a dog train, and he subsequently painted a watercolour titled The winter packet (1903) and fashioned a wax group known as Transport to the northern lights (c. 1903–5). A more satisfying encounter with his romantic fantasies was provided in November 1908 and the following spring, when he first observed and then participated in two round-ups on Montana’s Flathead Reservation of the more than 700 buffalo purchased by the Canadian government for delivery to Alberta. The experience reinvigorated his interest in buffalo and buffalo hunts as artistic subjects.

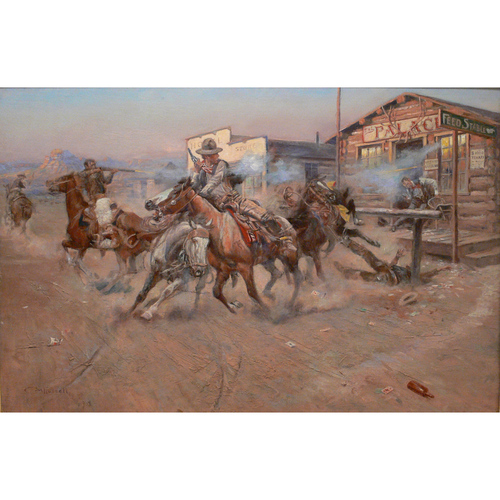

By then Nancy Russell was her husband’s business manager. In 1904 she had persuaded him to make the first in a series of trips to New York. His paintings were already widely familiar through postcards and colour reproductions, and he had his first bronze cast that year. Commissions for illustrations and a major calendar contract followed, contributing to the view that, after Frederic Remington’s death in 1909, Russell was North America’s premier western artist, an opinion confirmed by a successful, one-man exhibition at New York’s Folsom Galleries in 1911. Titled The west that has passed, it perfectly conveyed his nostalgic vision of cowboys, Indians, and wildlife in an unfenced land.

The next year Russell exhibited at the first Calgary Stampede, which brought him international attention and new patrons for his art. The show was a great success – 13 of the 20 catalogued paintings sold, three featuring cowboys to Sir Henry Mill Pellatt* of Toronto and four depicting Indians to a titled Englishman – and Russell was back in 1913 to exhibit at a stampede in Winnipeg. Contacts made in Canada led to his only exhibition overseas, at London’s Doré Galleries in 1914. He had enjoyed Canadian patronage before. In 1897 William Bleasdell Cameron*, representing an American sportsman’s journal, had commissioned six drawings to illustrate his personal memoirs of two months’ captivity in the camp of Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa*] following the attack at Frog Lake (Alta) in 1885. Engineer Charles Alexander Magrath* of Lethbridge in 1905 persuaded Russell to paint an oil portraying a pitched battle between Blackfoot, Cree, and Assiniboin fought in the immediate vicinity in 1870 [see Jerry Potts*]. Ordinarily, Russell sold generic scenes of Indian and cowboy life to Canadian patrons such as Jimmy Simpson, a Banff outfitter and guide, and William B. Campbell, an Alberta rancher who met Russell at the Winnipeg Stampede in 1913. But after his success in Calgary, he added specifically Canadian content to his repertoire by painting four major mounted police oils, one each year between 1912 and 1915.

The “big four” who had backed the first Calgary Stampede – George Lane, Alfred Ernest Cross*, Patrick Burns*, and Archibald James McLean* – were all connected to the Alberta cattle industry, and Lane became a major patron. When the Russells were lured back to Canada in 1919 for exhibitions at Calgary’s “Victory Stampede” and in Saskatoon, Cross bought a cowboy subject, while Burns acquired one of the mounted police oils, Whiskey smugglers caught with the goods (1913), and Lane two others, The queen’s war hounds (1914) and When law dulls the edge of chance (1915). The former he eventually donated to the province of Alberta; the latter was presented to the Prince of Wales, who, on an extended Canadian tour, had purchased the ranch next to Lane’s Bar U. Rising prices in these years demonstrate Russell’s artistic success; by 1920 a single oil commanded $10,000.

His links to the Canadian west took many forms. Between 1906 and 1910 he co-owned a ranch in the Sweet Grass Hills, five miles south of the Canadian border, and often visited southern Alberta, counting many friends among the cattlemen in the area. The Russells wintered in California in 1920, but Russell was always most at home in Montana and Alberta among those who spoke his language. After he died in 1926, A. E. Cross expressed what Russell’s passing meant for western Canadians. “You have not only my entire sympathy,” he wrote to Nancy Russell, “but the sympathy of all the old cow men in this country.” His death would be “a distinct loss, not only to your own Community, the United States, but all the world.” Charles M. Russell is still universally known as the “cowboy artist.”

Private arch., Jim Combs (Great Falls, Mont.), Materials pertaining to C. M. Russell. Taylor Museum, Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center (Colorado Springs, Colo.), Helen and Homer E. Britzman Coll., C.7.159 (A. E. Cross to N. C. Russell, 30 Oct. 1926); E.189 bi (N. C. Russell’s annotated copy of Special exhibition: paintings by Charles M. Russell, at “The Stampede, Calgary, 1912”); E.346 (The west that has passed, exhibition catalogue, Folsom Galleries, New York, 1911). “An artist visitor,” Edmonton Bull., 25 Feb. 1903: [3]. Charlie Russell roundup: essays on America’s favorite cowboy artist, ed. B. W. Dippie (Helena, Mont., 1999). H. A. Dempsey, “Tracking C. M. Russell in Canada, 1888–1889,” Montana: the Magazine of Western Hist. (Helena), 39 (1989), no.3: 2–15. B. W. Dippie, “Charles M. Russell and the Canadian west,” Alberta Hist. (Calgary), 52 (2004), no.4: 4–26. [C. M. Russell], Charles M. Russell, word painter: letters, 1887–1926, ed. B. W. Dippie (Fort Worth, Tex., 1993). John Taliaferro, Charles M. Russell: the life and legend of America’s cowboy artist (Boston, 1996).

Cite This Article

Brian W. Dippie, “RUSSELL, CHARLES MARION,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/russell_charles_marion_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/russell_charles_marion_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Brian W. Dippie |

| Title of Article: | RUSSELL, CHARLES MARION |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | March 30, 2025 |