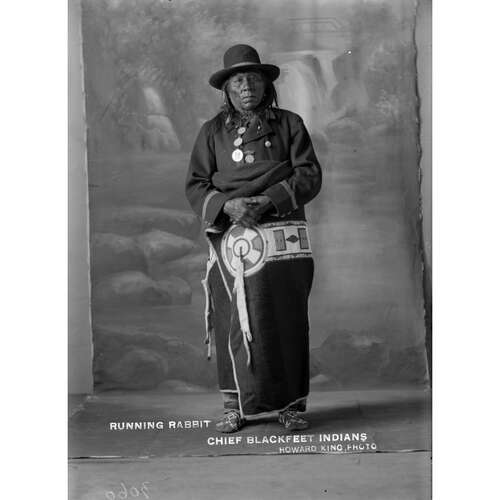

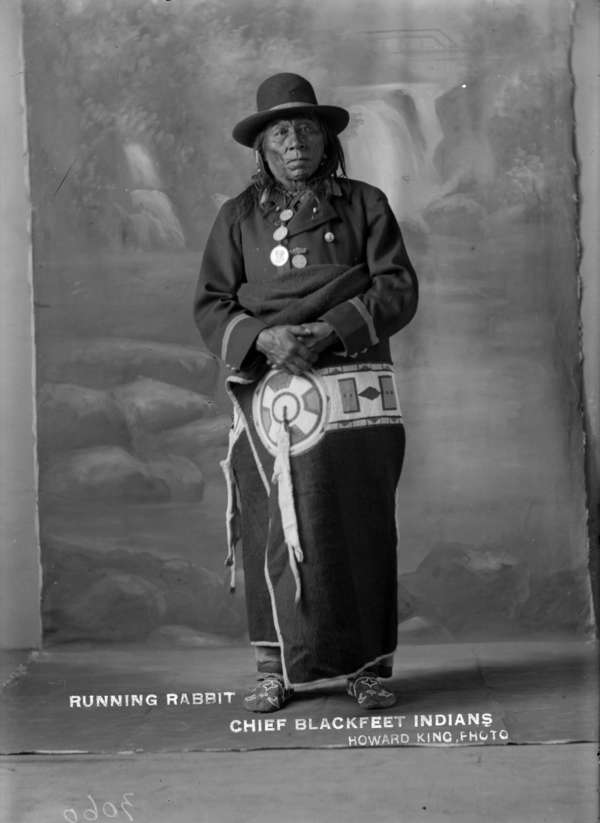

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

AATSISTA-MAHKAN (Running Rabbit), Blackfoot warrior, the leader of the Biters band, and a head chief of the tribe; b. c. 1833 in what is now central Alberta, son of Akamukai (Many Swans); had four wives and eleven children, the most prominent being Duck Chief, who later became a head chief; d. January 1911, probably on the 24th, on the Blackfoot Indian Reserve, Alta.

When Running Rabbit was a teenager, his elder brother Akamukai (Many Swans) was chief of the band. To encourage the young man to go to war, Many Swans lent him his spiritual protector, an amulet he had received through a vision. It consisted of a round mirror decorated with weasel skins and eagle and magpie feathers. On his first raid Running Rabbit captured two enemy horses, which he gave to his brother. Many Swans lent the amulet to him three more times and, because he was successful on each raid, finally gave it to him. During his career as a warrior, Running Rabbit killed 11 enemy in battle and captured numerous horses. People began calling him the “young chief” while he was still a teenager.

On the death of Many Swans, in the autumn of 1871, Running Rabbit became chief of the Biters band. A descendant described his leadership: “When Running Rabbit was among his band, his men were invited to eat, smoke, tell stories every day. He was generous. He gave his running horses out during hunts. Running Rabbit had four wives; two put up Sun Dances. He was kind to children and women.” Band members went to him to settle disputes. In the early 1870s, when the Blackfoot were camped on the Oldman River, the daughter of Crowfoot [Isapo-muxika*] was accidentally killed by a young man holding a loaded gun. The man immediately took refuge in Running Rabbit’s tepee because Crowfoot, one of the head chiefs, sought to kill him. Running Rabbit persuaded the chief that the shooting had been an accident and offered two of his own horses as compensation. He was a stern protector of his family, however. When an Indian began beating Running Rabbit’s blind brother with a whip, he shot and killed the man.

In 1877, along with Crowfoot, Old Sun [Natos-api*], and other leaders, Running Rabbit signed Treaty No.7 with the Canadian government on behalf of the Blackfoot tribe. He was appointed a minor chief and was listed as having 90 followers. By 1883 his band would number 156. In 1881, after the last buffalo herds had been destroyed, the Blackfoot were obliged to settle on their reserve, 60 miles east of what is now Calgary. Running Rabbit proved to be one of the chiefs who adapted to the new life most ambitiously. He camped near Blackfoot Crossing where he started a small garden and encouraged members of his band to become self-supporting. In 1887, after he had begun farming, he was particularly mentioned by Indian agent Magnus Begg as one of the Blackfoot who “deserve special mention as having worked well with their own ponies and with the work oxen.”

Running Rabbit was named one of the two head chiefs of the tribe in 1892, replacing the deceased No-okska-stumik (Three Bulls). He shared the leadership with Old Sun, but being much younger and more progressive, he often tended to speak for the entire reserve. He became known for his wisdom and his ability to remain free of intra-family problems. Besides controlling the tribal council with a firm hand, he continued to be a hard-working farmer. In 1898 he had his own wagon, mowing machine, and horse rake and had made enough money cutting and selling hay to buy a high-top buggy. He supported the introduction of cattle and the opening of coalmines.

Although the Blackfoot suffered bitter and difficult years after they settled on their reserve, Running Rabbit was a chief who was respected both by his people and by the government. At his death in 1911, he was compared to such great leaders as Crowfoot and Old Sun.

A portrait of Running Rabbit, painted in 1907 by Edmund Montague Morris, is in the Ethnology Dept. of the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (Edmund Morris coll., HK 2408), and the PAM holds a photograph of the chief. Both portraits are reproduced in The diaries of Edmund Montague Morris; western journeys, 1907–1910, transcribed by Mary FitzGibbon (Toronto, 1985), 19.

Canadian Museum of Civilization Library (Hull, Que.), Doc. coll. sect., Julian and Jane Hanks papers, box 301, file 10, esp. p.31 (Julian Hanks, interview with Spumiapi [a descendant of Running Rabbit] via Mary White Elk, 3 Sept. [1939]). Arni Brownstone, War paint: Blackfoot and Sarcee painted buffalo robes in the Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto, 1993). Can., Dept. of Indian Affairs, Annual report (Ottawa), 1887: 100; 1898: 126. J. [S.] McGill, “The Indian portraits of Edmund Morris,” Beaver, outfit 310 (1979–80), no.1: 34–41.

Cite This Article

Hugh A. Dempsey, “AATSISTA-MAHKAN (Running Rabbit),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 20, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/aatsista_mahkan_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/aatsista_mahkan_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hugh A. Dempsey |

| Title of Article: | AATSISTA-MAHKAN (Running Rabbit) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | November 20, 2024 |