As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

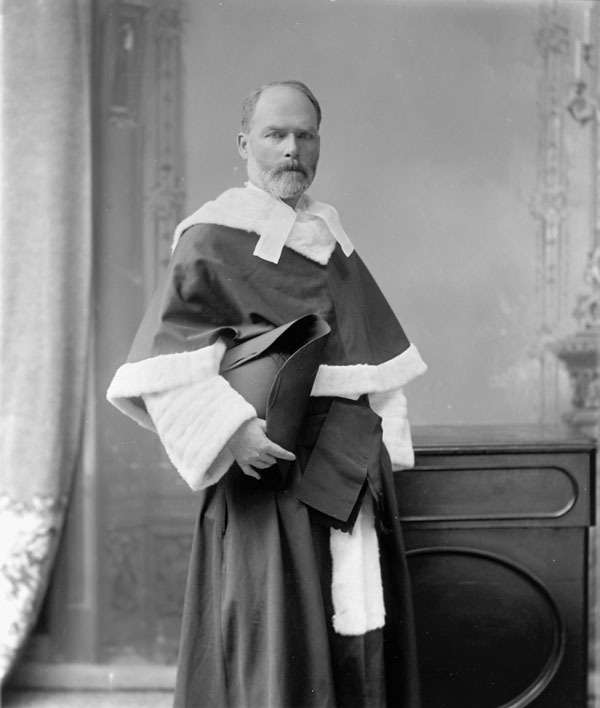

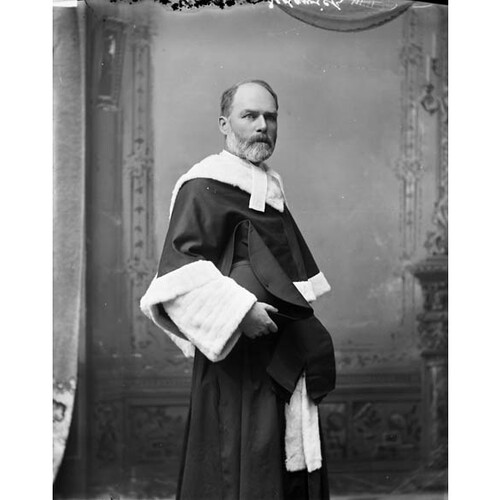

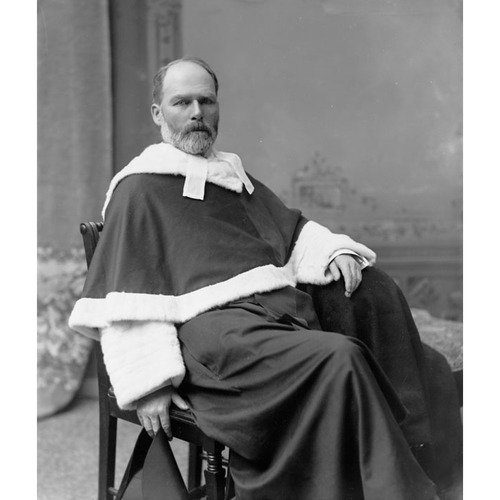

SEDGEWICK (Sedgwick), ROBERT, lawyer, educator, politician, civil servant, and judge; b. 10 May 1848 in Aberdeen, Scotland, fourth son and seventh child of the Reverend Robert Sedgewick and Jessie Middleton; m. 19 July 1873 Mary Sutherland MacKay in Fredericton, and they had three children, all of whom died in infancy; d. 4 Aug. 1906 in Chester, N.S.

Robert Sedgewick was an infant when his family immigrated to Nova Scotia, where his father was inducted into the Presbyterian charge of Middle Musquodoboit. A forceful preacher known throughout the province as the “old man eloquent,” the elder Sedgewick devoted much effort to improving the educational system, a preoccupation which would manifest itself in his son. In 1863 Robert Jr entered Dalhousie University, which had just reopened after a long period of dormancy. Having graduated with a ba in 1867 he decided to study law but took the unusual step of articling in Ontario. Even more unusual was the identity of his principal: John Sandfield Macdonald*, premier and attorney general of the province. Convention permitted the crown’s senior law officer to pursue a private practice and Macdonald retained his in Cornwall, which from 1868 became Sedgewick’s base for four years. How Sedgewick came to Macdonald’s attention remains a mystery, but their meeting probably occurred when Macdonald and Sir John A. Macdonald* visited Nova Scotia in 1868 to discuss “better terms” for the province under confederation. In any case, the connection gave Sedgewick’s career a useful impetus and eased his later transition from the local to the national scene.

Called to the bar of Ontario in 1872, Sedgewick returned to Nova Scotia in 1873. In spite of his absence, he retained enough influence to have a private act passed admitting him to the provincial bar after the Nova Scotia Barristers’ Society refused his petition. Sedgewick then plunged into professional and political activities. In 1874 he helped to form a discussion group called the Halifax Law Society, which included men such as John Thomas Bulmer and Benjamin Russell. All were ambitious young lawyers anxious to improve the status and standards of the profession; many of them became good friends. An attempt by Sedgewick and others to found a law school at Dalhousie in 1874 did not succeed, nor did an attempt to create one at the short-lived University of Halifax, on whose senate Sedgewick sat. Talent, ideas, and good intentions were not lacking; money was. This final impediment was removed through the decision of philanthropist George Munro* to fund a chair in law, allowing the Dalhousie law school to open its doors in 1883.

Dalhousie’s was the first university law school in the British empire to offer a degree in the study of the common law, and Sedgewick is acknowledged to have been the prime mover behind its establishment. The school drew its inspiration from the vibrant law schools of New England rather than from the moribund traditions of the mother country. Sedgewick and John Sparrow David Thompson* had travelled to Columbia and Harvard in April 1883 in order to gather ideas for the fledgling institution. The Dalhousie curriculum was, however, sui generis, emphasizing public and international law in addition to the traditional private law. Because the school for many years had only one full-time professor, Dean Richard Chapman Weldon*, most of the classes were given by members of the Halifax bar. Sedgewick led the way by lecturing free of charge in equity and commercial law for 15 years. His efforts on behalf of Dalhousie were not limited to the law school, for he also sat on the board of governors, became president of the Alumni Association, and led fund-raising efforts in the 1870s.

Energy, influence, and ambition he may have had, but money proved more difficult to come by. Lawyers found that government work was a necessity in the 1870s, which were lean years for the Nova Scotian economy. However, as a strong Conservative, Sedgewick got no commissions from the Liberals provincially or federally. He was virtually bankrupt by 1878, when his partner, John James Stewart, quit their firm. The economic upswing of the 1880s put him back on his feet, allowing him to take on several new partners; these included his brother James Adam, a member of the Dalhousie law school’s first graduating class, and William Benjamin Ross, a promoter who was able to attract much commercial business. The 1880s also marked the formal recognition of Sedgewick’s talents by the legal profession: he was appointed a qc in 1881 by Governor General Lord Lorne [Campbell*], and between 1880 and 1888 he was on the council of the barristers’ society, serving as vice-president from 1886 to 1887.

Political life attracted Sedgewick from an early age and he would remain a strongly partisan Conservative, though in his last years he nourished a secret admiration for Sir Wilfrid Laurier*. In 1872, while articling, he had assisted in the campaign of Conservative mp Walter Shanly*, and in 1874 he ran unsuccessfully for the Nova Scotia House of Assembly. He belonged to the circle of young professionals, among them Thompson and Stewart, who were associated with the revival of Conservative fortunes in Nova Scotia in the 1870s. Once his law practice had quickened, Sedgewick entered municipal politics in 1882 as an alderman, holding office until he succeeded Joseph Norman Ritchie as city recorder in 1885. As a member of the Halifax Board of School Commissioners during the early 1880s, he worked hard with his friend Bulmer to reverse the policy of racially segregated education the board had adopted in 1876.

Ten months after Thompson became federal minister of justice in 1885, Sedgewick solicited from him the position on the Nova Scotia Supreme Court vacated by the death of Samuel Gordon Rigby. Thompson had other plans, however, and brought Sedgewick to Ottawa as deputy minister of justice in February 1888. Sedgewick quickly made a name for himself as a competent, efficient, and fair administrator. Undoubtedly his greatest achievement was the drafting of the Criminal Code of 1892 in conjunction with George Wheelock Burbidge. Although various consolidations of the criminal statutes had been produced since confederation, the value of arranging all these laws in a single code was undeniable. The preparation of such a code presented formidable legal and political problems, however, as the unsuccessful attempts in England to enact Sir James Fitzjames Stephen’s draft code had shown. Only the combination of Sedgewick’s legal abilities and Thompson’s political skills could have sufficed to convince the legal profession of the value of the project and to shepherd it through parliament in 1892.

In form and substance the Criminal Code of 1892 was a perfect example of Canadian reformist conservatism. Sedgewick and Thompson were reformist enough to embrace the concept of codification, in spite of opposition to it by many eminent English legal authorities, but they refused to countenance the more idealistic and revolutionary notions of codification advanced by continental jurists and by American reformers such as David Dudley Field. To the latter’s argument that a code should be complete in itself, internally consistent, and drafted in language accessible to all, Sedgewick’s reply was curt: “That may be right in theory. It has never been found possible in practice.” As a result, the Canadian code maintained in force all previous common law not expressly or impliedly abrogated by it; not until 1955 would the code contain all criminal offences known to the law. While this organic and historical approach to legislation reflected in part a preference for evolution over revolution, it also arose from a desire to avoid being too lenient. “By retaining [the common law],” Sedgewick replied to a critic, “there will be no danger that our criminal law will be less lax than at present.” Nor was Sedgewick unduly impressed with arguments that the language of the criminal law needed to be simplified: although some progress was made in this area, much that was unwieldy, verbose, and obscure remained. None the less, the myriad major and minor criticisms which might have been made were less significant than the achievement itself. The Criminal Code of 1892 represented an important step in the consolidation of the power of the Canadian state and in the articulation of its identity; the legislation ensured that parliament rather than the judiciary would retain its primary role in setting policy with respect to criminal justice. One of the few contemporary critics of the general spirit of the new code was Mr Justice Henri-Elzéar Taschereau*, with whom Sedgewick would soon share the bench of the Supreme Court of Canada.

Work at the Department of Justice, while onerous, was varied and challenging. Sedgewick travelled to London in 1889 to argue before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council the dominion’s case for ownership of minerals in the British Columbian railway belt. (The dominion lost.) In 1891 he was off to Washington in connection with the dispute over the seal fishery in the Bering Sea. The previous year he had produced the Bills of Exchange Act, which as an exercise in codification served as a dress rehearsal for the Criminal Code. More surprising by modern standards, Sedgewick continued to play an active partisan role behind the scenes during elections.

On 18 Feb. 1893 Thompson bestowed upon Sedgewick the judgeship he had sought years earlier. The death of Chief Justice Sir William Johnston Ritchie* the previous fall had created a Maritime vacancy on the Supreme Court of Canada, which Sedgewick was well qualified to fill. The Legal News reviewed his appointment favourably, one of its Ottawa correspondents commenting that as deputy minister Sedgewick had been, “perhaps, the hardest worked officer in the service of Canada.” The Dalhousie law school seized the occasion to express its gratitude and granted Sedgewick an honorary lld at its spring convocation.

Sedgewick’s judicial career could not be called stellar, but the fortunes of the Supreme Court itself sank to a low ebb during his period in office. Plagued by serious personality clashes [see Sir Samuel Henry Strong], the court was unable to inspire much confidence in the bar. Few important constitutional cases were heard during Sedgewick’s time on the bench, and in several of these he did not sit (such as the Manitoba schools case of 1894) or did not write a separate opinion. Those cases in which he did write an opinion disclose a tendency to favour the federal government: in In re Prohibitory Liquor Laws (1895) he took an expansive view of the federal power over trade and commerce to deny the provinces the right to enact total prohibition, and a decade later he upheld a federal statute which forbade railways from contracting out of negligence claims by their employees. The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council agreed with the latter decision but overturned the former [see Sir Oliver Mowat]. In an important 1904 decision, In re Vancini, he affirmed the power of the dominion to give new criminal jurisdiction to provincially appointed inferior courts without the necessity of complementary provincial legislation. While not novel in view of precedents, the decision was crucial in maintaining the primacy and integrity of the federal role in the making of policy with regard to criminal law. His thinking on federalism shows no evidence of a regional or Maritime preoccupation, which is perhaps not surprising in view of his extensive involvement at the national level.

If Sedgewick’s experience in drafting the Criminal Code was largely wasted at the Supreme Court because of the paucity of criminal appeals, his expertise in commercial law was not. By far the majority of his reported decisions involve aspects of commercial law such as company law, insurance, contracts, and mining law. These decisions illustrate his strong commitment to classical liberal notions of freedom of contract and restricted intervention on the part of the state. He invariably gave exculpatory clauses their full effect, and in an impassioned dissent he urged the court not to strike down a clause in an insurance contract which forbade the insurer from contesting the policy after one year. Yet his commitment to a liberal world-view did not prevent him from protecting the weaker party when he felt there was a true inequality of bargaining power. He applied equitable principles to set aside a mortgage on her own assets which a debtor’s wife had been inveigled into signing by her husband and his creditor. In a case involving claims by Indians to certain annuities payable by treaty, Sedgewick declared that the natives were entitled to expect “not only justice, but generosity.”

The decisions which show Sedgewick in the least favourable light by modern standards are those involving accidents in the workplace and railway collisions. He was unsympathetic to claims by injured workers and their families and was quick to find contributory negligence by the victim, which was then a complete bar to an action. When employers were alleged to have been negligent, he demanded high standards of proof. In spite of an increasing number of laws respecting safety in the workplace, Sedgewick was reluctant to use breaches of these statutes to create presumptions of negligence or to found causes of action. The railways in particular could do little wrong, “the interests of the public in saving time and the increase of productive power” being sufficient justification in his eyes for their extensive immunity from suit. His anti-labour views, however, were hardly unique among contemporary Canadian jurists.

In methodology Sedgewick’s judgements are unusual for the period, often replete with detailed data on the socio-economic context of a particular legal dispute. Discussion of precedents is kept to a minimum, and factual matters are thoroughly canvassed. On the whole, his judgements are characterized more by the utilitarian preoccupations of the deputy minister than by the judge’s concern with legal principle, which is odd given that he was in the forefront of legal education in his time. Sedgewick’s written decisions were not numerous and seldom lengthy, and in later years a lingering illness, possibly cancer, restricted his output. He died, aged 58, while at his summer home in Chester during the 1906 recess. His estate amounted to a modest $10,000.

It would be difficult to disagree with the Canadian Law Times obituary assessment of Sedgewick’s judicial career: “He was not a great jurist, but he was a favourite with the Bar, a man of the world . . . with a fair knowledge of law, and a great knowledge of human nature.” However, it is not as a judge that Robert Sedgewick should be remembered, but as a legal educator and civil servant of energy, talent, and vision. He was the central figure in the extraordinary renaissance of legal professionalism which occurred in late-Victorian Nova Scotia. His creative impetus was responsible for the Criminal Code of 1892 and the Dalhousie law school, two key elements in the formation of the modern Canadian legal tradition. In spite of undoubted opportunities to use his commercial law practice to achieve power, prestige, and fortune in the business world, he chose the path of public service and died in relative impecuniosity. For all his worldliness, the minister’s son retained some reservations about serving Mammon too directly.

AO, F 2132, MU 2386, Sedgewick to W. Ellis, 23 July 1872; RG 22, ser.354, no.4915. Halifax County Court of Probate (Halifax), Estate papers, no.6934. NA, MG 26, A: 142997; D: 3696, 4305, 20804; G: 103501; RG 13, A2, file 63/1894, Sedgewick to J. S. D. Thompson, 3 Feb. 1893. Acadian Recorder, 6 Aug. 1906. Halifax Herald, 6 Aug. 1906. Morning Chronicle (Halifax), 18 Feb. 1881, 12 Dec. 1883, 2 Feb. 1884, 6 Aug. 1906. D. H. Brown, The genesis of the Canadian Criminal Code of 1892 ([Toronto], 1989), 11–37, 70–91, 148, 163–64. Can., Statutes, 1890, c.33; 1892, c.29. Canadian Law Times (Toronto), 26 (1906): 664. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.2. Legal News (Montreal), 16 (1893). Musquodoboit pioneers: a record of seventy families, their homesteads and genealogies, comp. Jennie Reid (2v., Hantsport, N.S., 1980), 654–62. N.S., Statutes, 1873, c.94. SCR, vols.22–38. Snell and Vaughan, Supreme Court of Canada, 52–81. Waite, Man from Halifax, 70–71, 122–24. John Willis, A history of Dalhousie law school (Toronto, 1979), 17–25, 28–29,31–32.

Cite This Article

Philip Girard, “SEDGEWICK (Sedgwick), ROBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sedgewick_robert_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sedgewick_robert_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Philip Girard |

| Title of Article: | SEDGEWICK (Sedgwick), ROBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 28, 2025 |