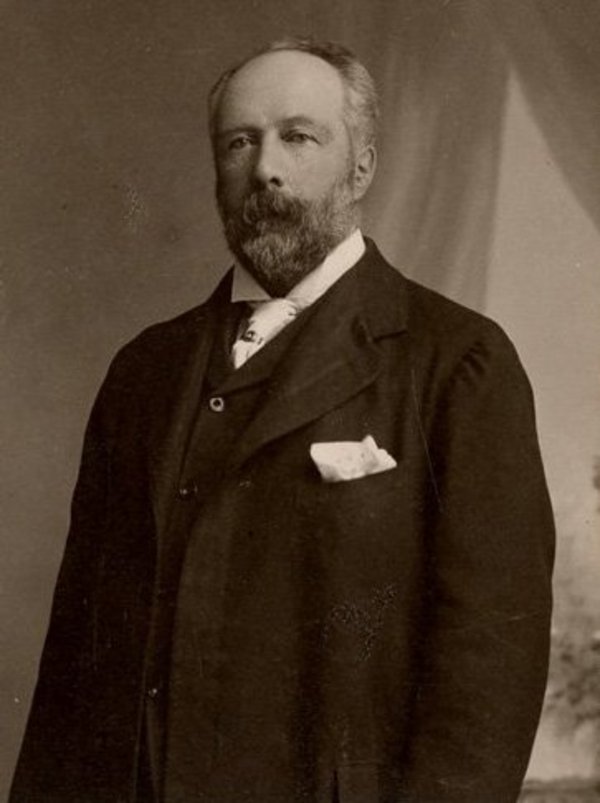

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

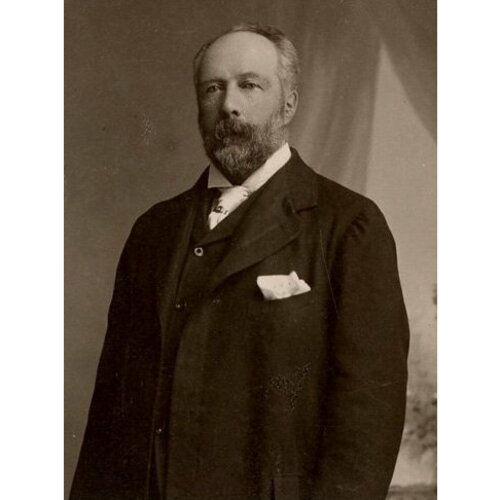

DOBELL, RICHARD REID, businessman and politician; b. 1837 in Liverpool, England, son of George Dobell, a merchant; m. 1866 Elizabeth Frances Macpherson, eldest daughter of David Lewis Macpherson*, and they had three sons and two daughters; d. 12 Jan. 1902 in Kent, England, somewhere between Hythe and Folkestone, of a head injury caused by falling from a horse.

Richard Reid Dobell spent his youth in Liverpool and studied at Liverpool College. In August 1857 he came to Quebec to enter the lumber business. He went into partnership with Thomas Beckett, his future brother-in-law, and in 1860 they set up in Sillery on the site of the LeMesurier and Brothers lumberyard. R. R. Dobell and Company maintained close ties with Liverpool merchants who provided it with a solid financial base throughout the 1860s. In 1867 it was considered by credit agencies to be one of the most reliable enterprises on the market, with a capital estimated at more than $500,000. When the prominent Liverpool traders James Bland and William and Hughes Pierce withdrew from the firm in 1873, it was reorganized. Quentin Fleming and Charles Taylor became the chief partners in Liverpool, although Bland’s influence was still dominant in matters of financing. He left at least £40,000 in the firm’s capital fund for a period of three years. With assets of £180,000, R. R. Dobell and Company enjoyed an impressive line of credit in Liverpool; it had an open account of £40,000 at the Bank of England and was given preferential treatment by A. Heywood and Son Company, a private financial institution.

The company weathered the depression of 1873–79 with some difficulty. Adopting a cautious policy, Dobell and Beckett decided to limit their use of credit. At the beginning of 1876 they were paying cash for their purchases and substantially reducing their orders in lumbering regions. However, facing competition on the British market from other exporting countries, and increased freight rates and charges for handling and loading at Quebec, they postponed dealing with problems related to the financial consolidation of their enterprise. The competition and increased rates and charges had significant consequences, both long- and short-term, and they may explain the withdrawal of the British partners, Fleming and Taylor. In 1879 Dobell and Beckett assumed primary responsibility for the company’s commercial future.

This change did not come about smoothly. In 1879 R. R. Dobell and Company had an estimated capital in the range of only $75,000 to $100,000. It had new challenges to meet, and with the 1880s came a period of rebuilding. Realizing that Quebec was no longer the leading port for the shipment of forest products, the partners also used Montreal (where they opened a branch office) and New York, as well as other ports in the United States; costs of transportation, handling, and loading were much lower in those places. They also diversified their sources of supply, not hesitating, for example, to send an agent to Honduras to get the mahogany they needed for the British market. Lastly, they moved their business office in England from Liverpool to London.

All these moves had an immediate effect on the company’s financial health. In the space of a few years R. R. Dobell and Company virtually recovered its earlier status. By 1887 it had accumulated minimum assets of $300,000 to $400,000. This growth led to a reorganization. In 1886 two commercial firms were formed: Dobell, Beckett and Company at Quebec and Richard R. Dobell and Company in London. Thomas Stevenson became their agent in the British capital, and Lorenzo Evans worked with Dobell and Beckett at Quebec. Dobell took on the task of managing the enterprises. The terms of the partnership were highly advantageous to him. He held 39 per cent of the shares, received an annual salary of $15,000, and could withdraw at any time, taking out the entire $450,000 in capital and profits that he had invested in Canada. His commanding position was strengthened in 1894, when Beckett left Quebec to join Stevenson in London, and Dobell’s son, William Molson, was brought into the partnership at Quebec. Although the new arrangement gave Dobell only 34 per cent of the shares, he now drew an annual salary of $25,000 and was still the wealthiest of the shareholders. Even more important, he was no longer required to devote all his time and energy to making the business run smoothly. His enterprises were well established, although their capital declined slightly to between $250,000 and $300,000 by 1893. Nevertheless, they continued to make a good showing and towards the end of the 19th century they even received profitable contracts from the British Admiralty to provide timber.

Freed from business responsibilities, Dobell played an increasingly significant role on the Canadian economic scene. He was already a key figure in the business community of the country, influencing the direction of the national economy. Active in the Quebec Board of Trade from his early days in Canada, he was its president in 1873 and again in 1895. During the 1890s he also served on commissions studying winter navigation and the export trade in livestock. As a member of the Quebec Harbour Commission in the 1880s, he participated in making the decisions involved in the construction of the Louise Basin; he was re-elected to the commission during the 1890s. His frequent journeys to England from 1885 and his business connections gave him both commercial and political credibility. He supported the idea of an imperial customs-union, and was associated with the federal Conservative party, which was pursuing such a goal. That is no doubt the reason why he was the Dominion Board of Trade’s delegate to London in 1892, and why he represented Canada’s interests in Cape Town (South Africa) that year. In 1894 he helped organize the conference of international chambers of commerce held at Quebec in July. He increasingly supported a reform of protective tariffs, commercial reciprocity between colonies with preferential treatment for Great Britain, and openness to trade with the United States.

In 1895 Dobell decided to run for the House of Commons in a by-election in Quebec West. His opponent was Thomas McGreevy*, who was seeking re-election after his difficulties with the law. Both men stood as independents but borrowed their platforms to a certain extent from those of the Liberals and Conservatives. Though still associated with the Conservatives, Dobell spoke out for some kind of free trade with the United States. He succeeded in winning support from Liberal francophone and Irish voters by taking a public stand in favour of the demands of the French-speaking minority on the Manitoba school question [see Thomas Greenway]. He was elected by a narrow majority of seven votes, a result that was immediately contested. The recount gave the seat to McGreevy by the same majority. Nevertheless Dobell had no hesitation in running as a Liberal for Quebec West in the general election of 1896. Although he again publicly declared himself an independent, his platform was similar to that of the Liberals. Despite the manœuvrings of the Conservative party, McGreevy again stood as an independent, but many of the Quebec business élite supported Dobell, and he won by 231 votes. On 13 July he was sworn in as minister without portfolio in the cabinet of Wilfrid Laurier*.

This appointment displeased his erstwhile colleagues. In the House of Commons, Thomas Chase-Casgrain* accused him of political opportunism. Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper* went even further, making the malicious claim that he could be bought for five dollars. Dobell countered by referring to the lack of ethics they had shown, especially in forcing Sir Mackenzie Bowell* to resign as prime minister. The Conservatives did not forgive him for his sudden change of allegiance. In the 1896 session, running from 19 August to 5 October, Dobell was acting minister of the interior. He soon crossed swords with the opposition in debates about the opening of a rapid steamship route between England and Canada. The project, which had been put forward by the cabinet of Sir John A. Macdonald* and in which the leader of the opposition, Sir Charles Tupper*, had played an important role, served Dobell’s interests. In fact, he was one of the leading promoters and shareholders of two Quebec firms, the Louise Wharfage and Warehouse Company and the Quebec Cold Storage and Warehouse Company, that would certainly profit from such a link. However, the project as championed by Dobell was sharply criticized by the Conservatives. Chase-Casgrain, for one, was puzzled by a statement from the minister confirming that Quebec would be the ocean terminus but hinting that the maritime route might extend to Montreal. Sir Charles Tupper criticized Dobell for wanting to inaugurate a route with steamships making only 18 knots instead of the 20 knots initially planned. He also mentioned a possible conflict of interest because of Dobell’s apparently close business connections with the Cunard Steamship Company. In fact, a number of financial considerations led the Laurier cabinet to favour a slower service than the one first envisaged by the Conservatives. Speaking for the government, Dobell maintained that ships doing 18 knots could compete favourably with transport on the New York-Liverpool route provided refrigeration compartments and larger cargo space were added, improvements not considered by Tupper during the previous negotiations. Even the annual subsidy, originally set at $750,000 by the Liberals, was reduced by Dobell to $500,000, a figure more in keeping with the size of the Canadian budget.

However, in 1897 the development of British naval engineering technology opened up the possibility of a transoceanic link using ships that travelled at more than 20 knots with a displacement of 10,000 tons (an increase of 1,500), additional cargo capacity, and more passengers. On Dobell’s recommendation, the contract for providing this service was awarded to Petersen, Tate and Company, of Newcastle upon Tyne, England, rather than the competing Allan Line, much to the discomfiture of the Conservatives. With an annual grant of $750,000, paid jointly by Canada and the British government, the firm undertook to construct by 1 May 1900, and to operate for a ten year period, four transatlantic steamships that would sail between Liverpool and Quebec. Some questionable dealings on the London stock market, a strike of shipyard workers in England in 1897, and the Spanish-American War of 1898 so undermined the project that the Laurier government acknowledged its collapse in the latter year.

It was a stinging defeat for Dobell. His development strategy for the Quebec region centred primarily on this engine of growth, which with the completion of the Great Northern Railway would have had a major effect on the city’s economic development. Despite the set-back he continued to champion vigorously Quebec’s ambition to become the principal shipping port for the St Lawrence sea route. Since 1890 favourable economic conditions had made it possible for three grain elevators and a refrigerated warehouse, all technologically advanced, to be added to the infrastructure of the Louise Basin. Dobell had obtained a federal grant of $350,000, which induced the Quebec Harbour Commission in 1898 to launch a huge modernization scheme. New sheds were built, railway tracks were extended to the wharves and warehouses, the deep-water docking area was enlarged, and sites were electrified. In addition, the opening of the Great Northern Railway provided access to a substantial volume of western goods for export. These improvements led the Leyland Line to transfer its terminus from Montreal to Quebec in 1901. However, two years later a group under William Mackenzie* and Donald Mann* gained control of the Great Northern and moved its head office to Montreal. The port of Quebec suffered heavily: revenues dropped by $1,400,000 on the reduced volume of merchandise carried by rail to the port, and the sole direct link with England was lost since the Leyland Line again made Montreal its terminus. Dobell, who had been returned in the federal election of 1900 in Quebec West and had remained in office as minister without portfolio, would not live to see the failure of his efforts. He died in January 1902 in England, where he had gone to recover his health.

Dobell left his mark on his day and age. A shrewd businessman, he had managed to develop his enterprise by taking into account new economic conditions. On the books of Dobell, Beckett and Company, his interest at the time of his death amounted to $619,476, exclusive of the various timber coves he owned (LeMesurier, Cape, and Anse des Mères). His efforts, both as a merchant and as a politician, to improve the infrastructure of the port and the commercial position of Quebec are also significant, even though his success was limited. In many respects, Dobell heads the list of businessmen, such as John Ross, James Gibb Ross*, William John Withall*, Pierre Garneau, and Andrew Thomson, who reacted to the city’s decline by suggesting new alternatives for growth but were still unable to keep Montreal from prevailing. His stock portfolio reflected his attachment to his city. He held shares in the. Quebec Jacques-Cartier Electric Company, the Montmorency Cotton Mills Company, the Quebec, Montmorency and Charlevoix Railway Company (which became in 1899 the Quebec Railway, Light and Power Company), the Quebec Cold Storage and Warehouse Company, the Quebec Terminal Company, and the Quebec Bridge Company. Dobell had also invested in enterprises outside the city, such as the Bank of Montreal, the Molsons Bank, the Canadian Pacific Railway, the Great Northern Railway, and the Port Hood Coal Company in Nova Scotia.

In 1892 Sir Charles Tupper had referred to Dobell as “one of the leading merchants of Canada.” He was indeed more than just a promoter of local development. In his actions and speeches he expressed a vision of a Canada being born, a country where the founding nations would merge into a homogeneous whole, remaining attached to Great Britain but not alienating their American neighbour. He shared the doctrine of Canadian autonomy that Laurier so fervently defended.

A man of wealth, Dobell lived in the luxurious villa of Beauvoir in Sillery. He also owned several parcels of land in the parish of Saint-Colomb-de-Sillery and a residence in Ottawa. His villa was filled with artistic treasures, including canvases by Cornelius Krieghoff*, Otto Reinhold Jacobi, John Constable, Guido Reni, and other English and Italian painters. His library was also well stocked, containing works by Charles Dickens, Plutarch, Edmund Burke, Francis Parkman*, François-Xavier Garneau*, Thomas Babington Macaulay, and Joseph Addison. His philanthropy was well known. He lent a hand to many public fund-raising campaigns, including one in aid of the French-speaking citizens of Hull following the fire of 1900, and one to erect a monument in Sillery to the first Jesuit missionaries. However, the main beneficiaries of his generosity were anglophone charitable organizations in Quebec, including the Finlay Asylum, St Bridget’s Asylum, the Ladies’ Protestant Home of Quebec, Jeffery Hale’s Hospital, and the Quebec Young Men’s Christian Association.

AC, Québec, Minutiers, W. N. Campbell, 11, 25 juin, 10 août 1896; 28 avril, 2 juill. 1902; E. G. Meredith, 17 août 1886, 24 oct. 1894. ANQ-Q, CM1-6, 10 févr. 1902; CN1-51, 25 juin 1875; T11-1/28, nos.1441–42 (1873); 29, nos.2305–6 (1879), 3671 (1886); 30, nos.5726–27 (1894). Baker Library, R. G. Dun & Co. credit ledger, Canada, 8: 258. L’Électeur, 2 oct. 1883; 3 juill. 1891; 9, 13 juin, 16–18 juill. 1894; 9–11, 15–16, 18, 24–25 avril 1895; 18 avril, 2, 5, 9, 16, 19–20, 22 juin 1896. Quebec Chronicle, 13 Jan. 1902. La Semaine commerciale (Québec), 17 juill., 15 nov. 1895; 10 janv., 21 févr., 31 juill., 27 nov. 1896; 17, 26 févr., 13 août 1897; 14 mars, 20 mai, 10 juin, 15 juill., 5 août, 23 déc. 1898; 21 avril 1899; 12 janv., 25 mai, 7, 28 sept. 1900; 25 janv., 10 avril, 14 juin, 23 août 1901; 23 janv., 6 févr., 24 mars 1903; 1er, 22 janv. 1904; 24 févr., 24 mars 1905; 12 avril 1907. Le Soleil, 1er–2 mars, 12 avril 1897; 13–15 janv. 1902. Benoit, “Le développement des mécanismes de crédit et la croissance économique d’une communauté d’affaires.” André Bernier, Le Vieux-Sillery ([Québec], 1977), 24. Bradstreet commercial report, 1867, 1875, 1878–79, 1887, 1891–96, 1899–1902. I. S. Brookes, The lower St. Lawrence: a pictorial history of shipping and industrial development (Cleveland, Ohio, [1974]). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1896–1901; Royal commission on labour and capital, Report. Canada Lumberman (Toronto), 23 (1902), no.4. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). O.-A. Coté, “La Chambre de commerce de Québec,” BRH, 27 (1921): 26–28. CPG, 1897–98. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.2. France Gagnon-Pratte, L’architecture et la nature à Québec au dix-neuvième siècle: les villas ([Québec], 1980), 194–97. John Keyes, “The Dunn family business, 1850–1914: the trade in square timber at Quebec” (phd thesis, Univ. Laval, Quebec, 1987), 383–84. Mercantile agency reference book, 1867. Poulin, “Déclin portuaire et industrialisation,” 90.

Cite This Article

Jean Benoit, “DOBELL, RICHARD REID,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dobell_richard_reid_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dobell_richard_reid_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean Benoit |

| Title of Article: | DOBELL, RICHARD REID |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 30, 2025 |