As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

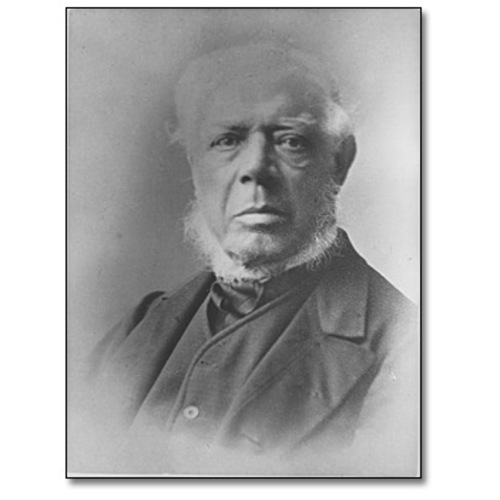

![Photo: George Theodore Berthon, [before 1893]. Archives of Ontario, M. O. Hammond fonds, Reference Code: F 1075-12-0-0-61. Original title: Photo: George Theodore Berthon, [before 1893]. Archives of Ontario, M. O. Hammond fonds, Reference Code: F 1075-12-0-0-61.](/bioimages/w600.12233.jpg)

Source: Link

BERTHON, GEORGE THEODORE, painter; b. 3 May 1806 in Vienna, son of Théodore-René Berthon and Françoise-Desirée Maugenest; m. first 1840, probably in France, Marie-Zélie Boisseau (d. 18 July 1847 in Toronto), and they had one daughter; m. secondly 14 Aug. 1850 Claire (Clare) Elizabeth de La Haye in Toronto, and they had six sons and five daughters; d. there 18 Jan. 1892.

George Theodore Berthon was born at the “royal palace” in Vienna, where his father, known as René-Théodore, who was court painter to Napoleon and a former student of Jacques-Louis David’s, was executing a commission for the emperor. The Berthon family returned to Paris that year, René resuming his activity as peintre ordinaire at the French court.

The younger Berthon is thought to have received his formal art training from his father. As a resident of Paris, he also had the opportunity to study the work of the old masters and the best contemporary French artists. At age 21 he immigrated to England, possibly to study medicine. He is believed to have lived initially in the home of the Tory politician and art collector Robert Peel, where he taught Peel’s elder daughter drawing and French in exchange for English lessons. Although his supposed medical studies remain only conjecture, it is known that Berthon was active as a painter, exhibiting portraits at the Royal Academy of Arts (1835–37) and the British Institution (1837–38). During this period he would also have been exposed to the work of the foremost exponents of the British portrait tradition, such as George Romney, Thomas Lawrence, and Joshua Reynolds.

Taking up a challenge

The last record of Berthon in England is his participation in the 1838 exhibition of the British Institution. Details of his subsequent whereabouts are sketchy until he advertised his services as a portraitist “from London” in Toronto’s British Colonist on 1 Jan. 1845 and later in other local newspapers, notices that indicate he had settled there. (Secondary accounts that date his arrival as early as 1840 or state that he had painted “in Canada” from 1837 to 1841 before returning to England and then settling in Toronto cannot be verified.) Berthon’s move might have been suggested by Peel or perhaps by the German-British painter Hoppner Francis Meyer, who had been active in Toronto and Quebec City at various times throughout the 1830s and early 1840s and who was later based in London. Regardless of the circumstances surrounding his decision, Berthon was evidently ready to accept the challenge of a new environment. According to tradition, he promoted himself and gained access to Toronto’s tory-dominated social circles on the basis of letters of introduction from Peel. Indeed, by April 1845 his wife was conducting a salon for young ladies in the couple’s William (Simcoe) Street home. This enterprise was patronized by the wives of several prominent members of the “family compact,” including Eliza Boulton, wife of Henry John*, and Emma Robinson, wife of John Beverley*.

Finding success

Berthon’s sophisticated European training quickly attracted the attention of local art patrons, most of them with tory affiliations, and important portrait commissions were soon acquired. His earliest pictures included likenesses painted in 1845 of such noted Torontonians as Bishop John Strachan* and Chief Justice John Beverley Robinson. He also executed a variety of productions for the Boulton and Robinson families, the best known being two works now in the Art Gallery of Ontario: the full-length portrait done in 1846 of William Henry Boulton* and the elegant and stylish Three Robinson sisters (Augusta Anne, Louisa Matilda, and Emily Merry). The latter painting, a gift to Emma Robinson, their mother, was commissioned in secret by Augusta’s husband, James McGill Strachan*, and by George William Allan and John Henry Lefroy*, who were soon to marry Louisa and Emily. It was presented on 16 April 1846 after Mrs Robinson’s return home from the wedding. The Boulton portrait, one of the foremost examples of the grand manner tradition in Canadian portraiture, is characterized, as are Berthon’s smaller bust and half-length likenesses, by tight brushwork, crisp delineation of forms, and fresh, clear colour – hallmarks of French neo-classicism exemplified in the work of such artists as David, with whose style Berthon would certainly have been familiar.

Obstacles

In 1847 Berthon submitted three portraits to the first exhibition of the Toronto Society of Arts [see John George Howard*], the second attempt on the part of local artists and architects to promote the visual arts by means of annual exhibitions. A series of lengthy commentaries on the event appeared in the British Colonist; its critic, however, made no mention of Berthon’s contributions, preferring instead to tout the merits of such “native Canadians” as Peter March and Paul Kane*. Berthon’s nationality caused a similar problem in 1848 when a controversy arose over a prospective commission to paint the “official” portrait of the former speaker of the Legislative Assembly, Sir Allan Napier MacNab*. While George Anthony Barber*, editor of the Toronto Herald, came out in support of Berthon, describing him as a “most accomplished artist,” the British Colonist, a reform paper owned by Hugh Scobie*, took a firm nationalist stance, stating that the commission, highly coveted, should go to the Canadian-born March. The portrait was eventually painted by the French Canadian artist Théophile Hamel*. Despite these initial obstacles Berthon continued to be patronized steadily by the local élite, who were by now even more aware of his evident professionalism. In 1848, for example, he completed a group portrait of the chief justices of Upper Canada for the Legislative Council. He received this commission on the basis of a recommendation from Robinson, who stated that he did not “suppose that a person could be found in Canada so likely to give satisfaction.” Berthon did not, however, participate in the second, and final, exhibition of the Toronto Society of Arts, held in 1848, possibly because of the MacNab controversy and because Berthon’s rival, Peter March, was the society’s secretary for that year.

Berthon is known to have visited the United States in 1852. Returning to Toronto the same year, he resumed his portrait work. During this decade, and for the remainder of his career, Berthon’s clientele expanded beyond the confines of the tory establishment to include all groups in the community, most notably the growing numbers of prosperous merchants and bankers. In 1856 the Law Society of Upper Canada commissioned a portrait of one of its chief justices, marking the beginning of what would develop into a lengthy term of patronage on the part of this group. Later subjects painted for the society included William Henry Draper* and John Douglas Armour.

Throughout his career Berthon’s participation in public exhibitions was minimal, the writer of his obituary being moved to note that his was “a name well known to artists, although to the public he was little known.” Indeed, his official, academy-inspired art would have seemed incongruous at the Provincial Exhibition, a venue better suited to the smaller landscapes and genre pieces by such artists as Paul Kane, Daniel Fowler, and Robert Whale*. He might also have been discouraged by the lukewarm reception of the paintings he had put on display in 1847. Perhaps the most likely reason for his absence from the public arena was the fact that he had a regular clientele and thus never felt the need to promote his work too vigorously.

Berthon did contribute portraits to the annual exhibitions of the Ontario Society of Artists [see John Arthur Fraser] in 1875 and 1877, and he was made a life member in 1891; however, in competition as he was against the prevailing taste for landscape, he continued to encounter critical disparagement of his pictures for both their size and their formal nature. Recognition on an international level occurred in 1876, when Berthon’s An early visitor received a gold medal at the Philadelphia Centennial International Exhibition, obviously a more challenging forum for a French-trained artist. (The painting’s current location is unknown.)

Although Berthon’s renown was such that he was named a charter member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts [see John Douglas Sutherland Campbell*] in 1880, his failure ultimately to submit the required diploma picture, perhaps because his creative energies were then being diverted in another, more lucrative direction, caused his nomination to expire. That year he had been invited by Lieutenant Governor John Beverley Robinson to execute a series of portraits of those who had formerly held the office, which would hang in the Government House [see Henry Langley*]. Working from sources such as engravings, photographs, miniatures, oils, and water-colours, Berthon produced over twenty posthumous portraits of noted figures in Canadian history, including Sir Francis Bond Head*, Sir Isaac Brock*, and military commander Sir Frederick Philipse Robinson. The entire project, rooted in the tradition of “halls of fame” and “portrait galleries,” was later extended to include portraits by Berthon of the governors general of the Province of Canada.

Berthon continued to paint until just a few days before his death, from a bronchial infection, at his Toronto home. On 30 March 1892 his private collection of paintings, which included a portrait of Napoleon by his father, an original Watteau, and various copies after old masters, was offered for sale.

Assessment

Berthon is known to have painted the occasional landscape and genre subject, usually at the request of a client, and appears to have supplemented his income by teaching privately now and again. He is also thought to have designed the iron gates in the fence at Osgoode Hall, intended to prevent cattle from straying onto the property. His reputation, however, rests solely on his work as a portraitist. For most of his career his style was based on such neo-classical precepts as strong draftsmanship, controlled brushwork, and clarity of local colour, combined with an evident commitment to realism. Towards the end of his life, like most Canadian artists who had become acquainted with pleinairisme and Impressionism, he adopted a looser, more fluid brushstroke and a softer palette. By this time there were other artists active in the field of establishment portraiture in Toronto, including Robert Harris*, John Wycliffe Lowes Forster*, and Edmund Wyly Grier*.

As Toronto’s foremost exponent of the portrait tradition during the Victorian era, Berthon produced a body of work that serves as an important historical record and as a prime example of the grand-manner style in Canadian portraiture. His long and prolific career reflects the continuing growth and prosperity of Ontario, the rise of Toronto as an influential urban centre – politically, economically, and culturally – and the significance of public and private patronage in the promotion of the visual arts.

Representative portraits by George Theodore Berthon are held in several public collections, among them those of the Art Gallery of Hamilton (Hamilton, Ont.); the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s Univ. (Kingston, Ont.); the London Regional Art Gallery (London, Ont.); and, in Ottawa, the National Gallery of Canada and the Senate Chambers in the Parliament Buildings. Most of Berthon’s paintings are to be found in Toronto collections, including those of the Art Gallery of Ontario; the CTA; the offices of the Law Soc. of Upper Canada at Osgoode Hall; the Hist. Picture Coll. at the MTRL; the Government of Ontario Art Coll. in the Ontario Legislature Building; the Royal Canadian Institute; the Sigmund Samuel Canadiana Building at the Royal Ontario Museum; St Michael’s, Trinity, and University colleges of the Univ. of Toronto; and Upper Canada College. A. K. Carr, “The career of George Theodore Berthon (1806–1892): insights into official patronage in Toronto from 1845 to 1891” (m.phil. thesis, 2v., Univ. of Toronto, 1986) includes an extensive discussion of Berthon’s works, their current locations, and the publications in which they have been discussed or reproduced. A photograph of the gates Berthon is thought to have designed for the fence around Osgoode Hall appears in G. B. Baker, “Legal education in Upper Canada, 1785–1889: the law society as educator,” Essays in the history of Canadian law, ed. D. H. Flaherty (2v., Toronto, 1981–83), 2: 88.

Apart from two paintings now in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Queen Elizabeth and the Countess of Nottingham (1837?) and Edward Marsh (1842), little is known of Berthon’s output during the years he spent in England. Standard sources for documenting his participation in London exhibitions are three works by Algernon Graves: The British Institution, 1806–1867; a complete dictionary of contributors and their work from the foundation of the institution (London, 1875; repr. Bath, Eng., 1969), 43; A dictionary of artists who have exhibited works in the principal London exhibitions from 1760 to 1893 (3rd ed., London, 1970), 24; and The Royal Academy of Arts . . . (8v., London, 1905–6; repub. in 4v., East Ardsley, Eng., 1970).

AO, MS 4, 22 Nov. 1845, 8 Aug. 1882. Art Gallery of Ontario, Arch. (Toronto), Art Gallery of Toronto corr., 1900–12, J. B. Robinson to William Morris, 20 April 1846 (typescript copy in its Library, Berthon file); Library, G. T. Berthon, sitters’ notebook, 1866–91; R. F. Gagen, “Ontario art chronicle” (typescript, c. 1919). “Art and artists,” Saturday Night (Toronto), 23 March 1892: 12. J. H. Lefroy, Autobiography of General Sir John Henry Lefroy . . . , ed. [C. A.] Lefroy (London, [1895]). The valuable collection of pictures of the late Mons. G. T. Berthon (Toronto, 1892). British Colonist (Toronto), 1 Jan. 1845, 14 April 1848. Globe, 19 Jan. 1892. Herald (Toronto), 6 Jan. 1845; 30 March, 5 June 1848. Death notices of Ont. (Reid). Harper, Early painters and engravers. Royal Canadian Academy of Arts; exhibitions and members, 1880–1979, comp. E. de R. McMann (Toronto, 1981). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.2. Fern Bayer, The Ontario collection (Markham, Ont., 1984). W. [G.] Colgate, Canadian art: its origin & development (Toronto, 1943; repr. 1967). J. R. Harper, Painting in Canada, a history (2nd ed., Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1977). John Lownsbrough, The privileged few: the Grange & its people in nineteenth century Toronto (Toronto, 1980). N. McF. MacTavish, The fine arts in Canada (Toronto, 1925; repr. [with intro. by Robert McMichael], 1973). Edmund Morris, Art in Canada: the early painters ([Toronto, 1911]). D. [R.] Reid, A concise history of Canadian painting (2nd ed., Toronto, 1988); “Our own country Canada.” René Chartrand, “Military portraiture,” Canadian Collector, 20 (1985), no.1: 39–42. W. [G.] Colgate, “George Theodore Berthon, a Canadian painter of eminent Victorians,” OH, 34 (1942): 85–103. J. W. L. Forster, “The early artists of Ontario,” Canadian Magazine, 5 (May–October 1895): 17–22. C. D. Lowrey, “The Toronto Society of Arts, 1847–48: patriotism and the pursuit of culture in Canada West,” RACAR (Montreal), 12 (1985): 3 –44.

Bibliography for the revised version:

Arch. départementales, Indre-et-Loire (Tours, France), “État civil,” Théodore-René Berthon and Françoise-Desirée Maugenest, Tours, 30 frimaire, an VIII [21 déc. 1799]: archives.touraine.fr/ark:/37621/ms6dclhfjq0p/0aa078ea-329a-47d4-bd1f-07c3666aae06 (consulted 16 Sept. 2024). Globe, 18 Feb. 1908.

Cite This Article

Carol Lowrey, “BERTHON, GEORGE THEODORE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/berthon_george_theodore_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/berthon_george_theodore_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Carol Lowrey |

| Title of Article: | BERTHON, GEORGE THEODORE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | March 28, 2025 |