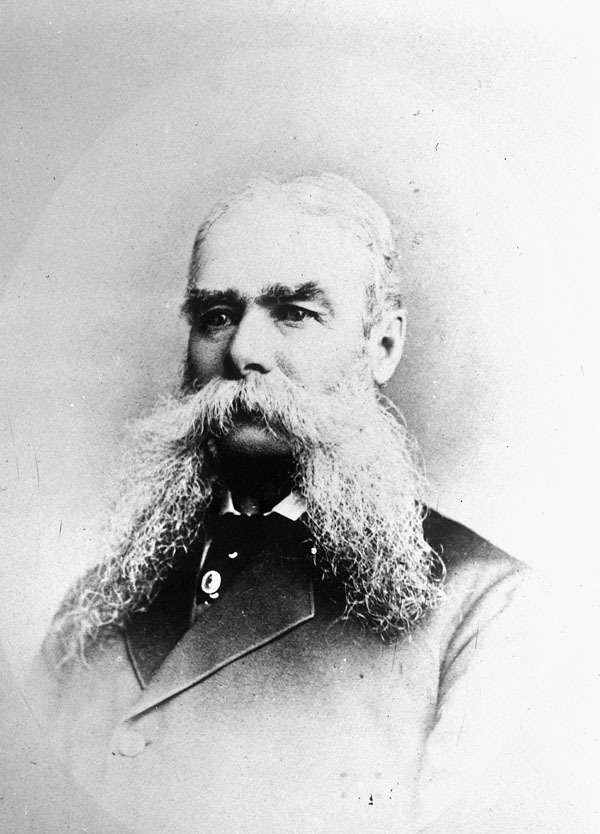

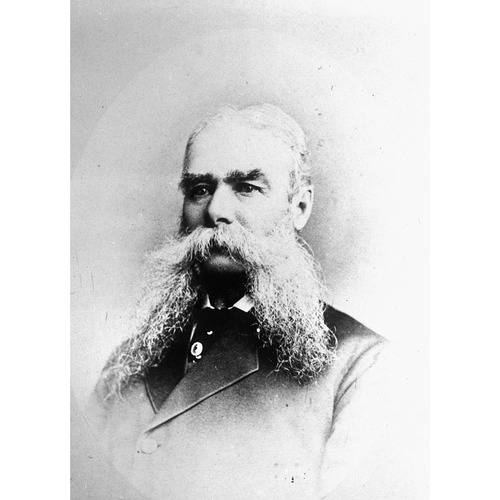

DENNIS, JOHN STOUGHTON, surveyor, militia officer, civil servant, and entrepreneur; b. 19 Oct. 1820 in Kingston, Upper Canada, eldest son of Joseph Dennis and Mary Stoughton; m. 13 Sept. 1848 Sarah Maria Oliver, and they had several children; d. 7 July 1885 at Kingsmere, Que., and was buried at Kingston.

John Stoughton Dennis was born into a family of relative affluence in which military virtues and loyalty counted for much. During the American revolution his grandfather, John Dennis*, supported the British and left his home in Philadelphia, eventually settling on the Humber River near York (Toronto); during the War of 1812 his father, Joseph, a lake captain, was captured and imprisoned by the Americans. About 1822 Joseph moved his family from the Kingston area to York, and then in 1830 to Weston. Here the Dennis family were to play a prominent role in the economic life of the community.

John Stoughton was educated at Victoria College in Cobourg, Upper Canada, and, after apprenticing with Charles Rankin, he qualified as a land surveyor on 4 Jan. 1842. His surveying career was an active one. Over the next two decades he surveyed a number of town sites along the projected routes of the Grand Trunk and Great Western railways; he registered the plan for Weston on 18 July 1846. He surveyed the Bruce Peninsula in 1855, and townships and colonization roads in the Muskoka, Haliburton, Parry Sound, and Nipissing districts between 1860 and 1865. In 1861 he began laying out ten townships for the Canadian Land and Emigration Company in the Minden-Haliburton area. He also surveyed various Indian reserves on the shores of lakes Huron and Superior. His professional competence had been recognized when he was appointed to the board of examiners for provincial land surveyors in 1851.

Although he lived in Toronto, Dennis maintained a keen interest in Weston, helping to secure the passage of the Grand Trunk Railway through it; he was also a member of the first board of the local grammar school. His concerns extended beyond local matters, to the institution for the deaf, dumb, and blind in Hamilton and to the Canadian Institute. Dennis was especially interested in the militia, believing himself “descended of martial ancestors.” In 1855 he was made a lieutenant of a cavalry troop, and in the following year commander of the Toronto Field Battery. In 1862 he was appointed brigade-major of the 5th Military District (with the rank of lieutenant-colonel), and he held the post until 1871.

Dennis first saw active service in June 1866 during the Fenian invasion. Somehow he secured temporary command of the 2nd Battalion, Queen’s Own Rifles [see William Smith Durie*], which was sent on 1 June to Port Colborne where Dennis was second in command to Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Booker*. Colonel George John Peacocke, the commander of the imperial troops on the Niagara frontier, instructed Booker to bring his force to Stevensville (now part of Fort Erie, Ont.) to await the Fenian attack. Dennis, believing the Fenians drunk and disorganized, beseeched Booker to attack immediately, but this scheme was rejected, though Booker later agreed to take independent action. Dennis commandeered the tugboat W. T. Robb, and began patrolling the Niagara River in an attempt to stop Fenian movements. On 2 June, Booker’s force, proceeding towards Stevensville, was attacked and defeated at Ridgeway by a force of Fenians led by John O’Neill*. In the afternoon of the same day, Dennis landed 70 of his men at Fort Erie in an attempt to find out where the Canadians were and to dispose of the prisoners he had taken. Some 150 Fenians appeared, but, confident of victory and unaware that more Fenians were coming up, Dennis urged his men forward. Following an exchange of fire, he ordered a retreat; the tugboat cast off without him and he was forced to disguise himself as “a labouring man.” He escaped, but 34 of his men did not.

An officer who had served at Fort Erie subsequently demanded an investigation into Dennis’ conduct, and another, who had lost a leg in the battle, publicly labelled him “a coward” and a “Poltrooney scoundrel.” Dennis requested a court of inquiry which examined charges by the officers, mostly of endangering his men unnecessarily but also of deserting them in the face of enemy fire. The court exonerated him completely but its president, George Taylor Denison* II, privately felt Dennis culpable of disobeying orders and published a dissenting opinion questioning his judgement.

After the embarrassments of 1866 Dennis returned to his surveying career. In 1869 he was sent by William McDougall*, Canadian minister of public works, to the Red River Settlement (Man.) as a temporary employee of the Canadian government to survey lots for prospective settlers. The Métis of Red River, who had not wanted the surveys undertaken in the first place, were doubly suspicious of Dennis when he stayed with Dr John Christian Schultz*, whom they heartily distrusted, after his arrival in August. The surveys, based on the American section system, seemed to threaten existing river lot holdings and, despite Dennis’ reassurances to them, the Métis under Louis Riel obstructed a survey team on André Nault*’s farm on 11 Oct. 1869. Dennis attempted in vain to persuade William Mactavish*, the governor of Assiniboia and of Rupert’s Land, to punish the perpetrators. Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* deemed this pressure by Dennis “exceedingly injudicious.” Dennis, he continued in a letter to McDougall, was “a very decent fellow and a good surveyor” but quite without a “head.” Surveys in the Métis area stopped but those elsewhere continued.

McDougall, as lieutenant governor designate of the North-West Territories, arrived in Pembina (N. Dak.) on 30 October, and Dennis journeyed south to meet him. On 21 October the National Committee of the Métis of Red River had ordered McDougall not to enter the settlement and Dennis and McDougall were turned back to Pembina by a Métis patrol on 3 November. They remained at Pembina until 29 November when Dennis returned to the colony with two proclamations, one announcing McDougall’s assumption of authority on 1 December, the supposed date of the transfer of the colony from the Hudson’s Bay Company to Canada, and the other naming himself McDougall’s “Lieutenant” and “conservator of the peace.”

The colonel established his headquarters at Lower Fort Garry and attracted “a motley crowd of 300”; he tried to ensure order among the volunteers by prohibiting liquor, but the attempt collapsed when he exempted himself. On 6 December a call “to all loyal men” produced a few more volunteers. Then, the following day, Schultz and a band of followers, barricaded in his Winnipeg warehouse, were forced to surrender to Riel, who proclaimed a provisional government on 8 December. Dennis, without either seeing or paying his men, disbanded them on 9 December and fled the colony two days later. His surveyors, who had been brought into the fort, were instructed to go back to their work, one of them being told specifically not to survey “beyond the limits of the English portions of the settlement.” Dennis returned to Ottawa with McDougall, leading Macdonald to reflect sourly that they had “done their utmost to destroy our chance of an amicable settlement” with the Métis. On 12 Feb. 1870 Dennis reported to Hector-Louis Langevin*, the minister of public works, that the people of Red River had not allowed the surveyors to proceed for fear of the Métis; he nevertheless took pride in the fact that they had surveyed 20,000 acres of farmland along the Red and Assiniboine rivers, ascertaining “present actual boundaries (but making no change whatever).” Two days later he assured Macdonald in a letter that he had “discharged” his duty “with prudence and judgment.”

On his return to Ontario Dennis served for a time as Lieutenant Governor William Pearce Howland*’s private secretary, and on 7 March 1871 his professional qualifications secured his appointment as Canada’s first surveyor general and head of the new Dominion Lands Branch. He made solid contributions as surveyor general. In March 1872 he produced a report which optimistically outlined the agricultural possibilities of the northwest. His office pushed ahead with the Manitoba surveys and after 1874 extended the base and meridian lines north from the 49th parallel to the North Saskatchwan River and west from Red River to the Rocky Mountains. For the most part Dennis remained in Ottawa, providing for corrections in the surveys already run, planning new and more detailed surveys, allocating the HBC lands, and trying to reassure the Indians and the Métis, as well as the few white settlers, that their rights would be respected. The possibilities of the west had clearly seized Dennis’ imagination, and he busily formulated a grand scheme in which Hudson Bay was to become a great commercial artery, funnelling people and produce in and out of the west.

On 14 Nov. 1878 Dennis became the deputy minister of the interior under Macdonald as minister. He won the post on merit; he had been no party war-horse, for, as he later informed Sir John, “I have never upon principle, since I have been in receipt of a salary from the Government, either as a staff officer of Militia or since I entered the regular Civil Service, cast a single vote.” Dennis did not toady to his minister, and in July 1879 they had a heated disagreement over the details of the disposition of the 100,000 acres of western railway lands. Macdonald proposed that the land be sold in 80-acre units, while Dennis argued for the new American system of 160 acres. Apparently Dennis carried the day, for the homestead units were raised to 160 acres. Macdonald praised Dennis’ work, which the latter found almost as gratifying as “a compliment (if such a thing could be imagined) coming from the Queen herself.”

As deputy minister, Dennis kept a sharp eye on the northwest; concerned over the depressed condition of the Indians and Métis, he urged the government to assist the Métis in becoming settled farmers by giving them cattle, technical training, and whatever else they needed, in the belief that they could then help civilize the Indians. His advice was ignored. In 1880 Dennis travelled to England with the Canadian delegation which was attempting to finance the Canadian Pacific Railway. The following year he joined Sir Alexander Tilloch Galt* on a tour of inspection of the west; it was a tiring journey for the ailing deputy minister who subsequently resigned his office on 31 December. He took comfort from the fact that he had helped to formulate public lands policy at a time “when the country was as a white sheet” and from the knowledge that his services were appreciated. On 24 May 1882 he was created a cmg.

During his retirement Dennis maintained close relations with his “dear old chief,” even contributing to Macdonald’s campaign fund in 1882. Although he had insisted that he had left office “poor and involved in debt,” he was able to invest in several private business concerns, including a consumers’ cooperative and a mining venture in what is now Alberta. His most cherished enterprise was Dennis, Sons and Company, established in 1882, with offices in England, to tender advice to prospective colonizers and immigrants. John Stoughton Dennis* Jr, also a prominent surveyor, was a member of the firm, and the company became involved in surveys in the northwest; political influence helped secure contracts.

Dennis was active until his death in July 1885. Although he may be remembered as a militia officer who was prone to leap upon his horse and ride off in all directions at once, he should also be recalled as an able administrator who made significant, lasting contributions to Canada.

AO, MU 1131, Skirving and Dennis families, W. W. Duncan, “Narrative of the Skirving and Dennis families” (typescript, March 1967); MU 2399. PAC, MG 26, A; MG 29, E74; RG 9, I, C8, 7. PAM, MG 3, B5; B11; B16-2; D1; MG 12, A; B. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1870, V: no.12. W. McC. Davidson, Louis Riel, 1844–1885; a biography (Calgary, 1955). G. T. Denison, History of the Fenian raid on Fort Erie; with an account of the battle of Ridgeway (Toronto, 1866), v, 22–91; Soldiering in Canada; recollections and experiences (2nd ed., Toronto, 1901). J. K. Howard, Strange empire; a narrative of the northwest (New York, 1952). J. A. Macdonald, Troublous times in Canada; a history of the Fenian raids of 1866 and 1870 (Toronto, 1910). E. B. Osler, The man who had to hang: Louis Riel (Toronto, 1961). Stanley, Birth of western Canada. D. W. Thomson, Men and meridians; the history of surveying and mapping in Canada (3v., Ottawa, 1966–69). V. B. Wadsworth, History of exploratory surveys conducted by John Stoughton Dennis, provincial land surveyor, in the Muskoka, Parry Sound and Nipissing districts, 1860–1865 . . . (n.p., 1926) (copy at AO). H. F. Wood, Forgotten Canadians (Toronto, 1963). Charles Unwin, “Col. John Staughton Dennis,” Assoc. of Ontario Land Surveyors, Annual report (Toronto), 29 (1914): 57–58.

Cite This Article

Colin Frederick Read, “DENNIS, JOHN STOUGHTON (1820-85),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 22, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dennis_john_stoughton_1820_85_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dennis_john_stoughton_1820_85_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Colin Frederick Read |

| Title of Article: | DENNIS, JOHN STOUGHTON (1820-85) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 22, 2024 |