Source: Link

ASSIGINACK (Assikinock, Assekinack), JEAN-BAPTISTE (also known as Blackbird), Ottawa chief and public servant; b. probably in 1768, perhaps at Arbre Croche (Harbor Springs, Mich.); d. 3 Nov. 1866 at Manitowaning on Manitoulin Island, Canada West. His second wife was Theresa Catherine Kebeshkamokwe and one of their sons was Francis Assikinack.

Jean-Baptiste Assiginack had apparently been a pupil at the Sulpician school at Lac-des-Deux-Montagnes (Oka) in Lower Canada and was converted there to Catholicism. He first comes to notice during the War of 1812. He may have taken part in the British capture of Michilimackinac in 1812 and of Prairie du Chien (Wis.) in 1814. In July 1813 Assiginack, as a chief of an Ottawa band, and Captain Matthew Elliott* led a number of Ottawas to the Niagara peninsula where they bolstered British strength after the battle of Beaver Dams and participated in a number of skirmishes. Assiginack may have received medals and a silk flag bearing the British coat of arms for his part in the war.

Following the war Assiginack was named in 1815 interpreter for the Indian Department at Drummond Island where he began a long friendship with Captain Thomas Gummersall Anderson*. “Sober, inoffensive and active,” according to Anderson, Assiginack became an indispensable part of the Indian Department’s operations in the northern Great Lakes area. Fluent in several Indian dialects, though apparently never comfortable in either English or French, he was the department’s chief interpreter in the Manitoulin Island region and an influential voice in the councils of his people.

In 1827 Assiginack heard that a Catholic mission was to be established at Arbre Croche. He resigned as interpreter at Drummond Island and went to Arbre Croche to assist at the mission. To his disappointment there was no priest there but he himself catechized and preached. In 1830 he led a group of Ottawas to Penetanguishene, where the British garrison had relocated after the transfer of Drummond Island to the United States in 1828, and returned to the employ of the Indian Department as interpreter. In 1832 he moved to Coldwater which he intended making his permanent residence. He had continued to preach at Penetanguishene and over the years had been successful in leading many bands of the northern lakes area to Catholicism. At Coldwater he was instrumental in the conversion of the prominent Ojibwa chief, John Aisance*, from Methodism to Catholicism. Assiginack impressed Methodist missionary Kahkewaquonaby* (Peter Jones) as “a very intelligent man, open & pleasant in his manner.” In January 1833 several chiefs at Coldwater petitioned Bishop Alexander Macdonell* that Assiginack “be appointed to perform service and to instruct us because he is a good man.”

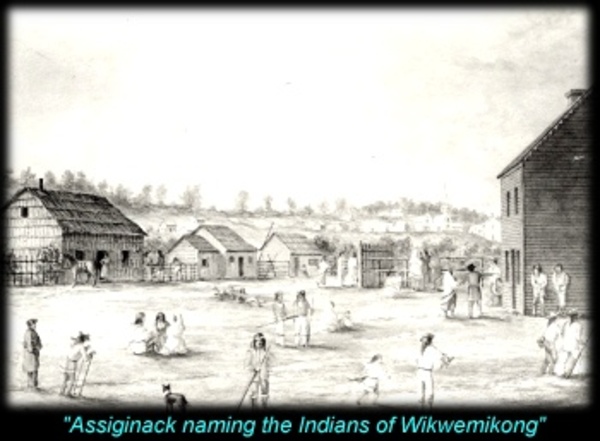

The Indian settlement at Coldwater was the result of the determination of the British authorities after 1830 to “civilize” the Indians by placing them in agricultural settlements. Coldwater was not successful, however, and in 1836 a bolder policy of encouraging the separation of the Indians from the white population was instigated by Lieutenant Governor Sir Francis Bond Head*. In that year Manitoulin Island was ceded to the Indians by a treaty, of which Assiginack was a signatory, and it was hoped that the village of Manitowaning (established the previous year) would become the focal point for the Indians on the island who were to adopt white ways and a mode of existence based on agriculture. Anderson was appointed northern superintendent of the Indian Department with headquarters at Manitowaning in 1837, and it was probably in the years that followed, until Anderson’s retirement in 1845, that Assiginack’s influence reached its height. Even after his own retirement from the Indian Department as interpreter in 1849, Assiginack remained an important link between his people and the government of the Province of Canada. He was active in the negotiations between the Indians of the upper lakes area and William Benjamin Robinson* which resulted in two treaties of 1850, and his help was also much valued by Superintendent George Ironside who succeeded Anderson.

On Manitoulin Island Assiginack bent all his efforts in the direction of Indian-white cooperation and of supporting plans to make the island a model Indian community. But as the decade of the 1850s passed, it became obvious that the original hopes for the island could not be met. It had not attracted as many Indians from central and northern Upper Canada as had been expected and the Ojibwa, who made up the bulk of the population of Manitowaning, continued to follow the traditional life based on hunting and fishing. Various tribes were represented in the island’s Indian population and the old tribal distinctions proved strong deterrents to communal efforts. Christianity itself was a divisive factor; the predominantly Ottawa and Roman Catholic village of Wikwemikong, established before Manitowaning and 18 miles to the east of it, continued to flourish in the 1850s while Manitowaning, which had been established by the government and was supported by the Church of England, gradually lost its Indian population.

With the failure of Manitowaning and of the Manitoulin Island experiment the decision was taken by the government in 1861 to open the island to white settlers. However, strong opposition to the surrender of the island was expressed in Wikwemikong. At a council meeting held at Manitowaning in October 1861 Assiginack made a powerful but unsuccessful appeal in favour of the acceptance of a treaty proposed by the government. Negotiations lapsed for a year until William McDougall*, the commissioner of crown lands, came to the island prepared to grant better terms than those previously proposed to the Indian population in return for the island’s surrender. Assiginack again supported the government position; at one council meeting he had to be protected by some of his sons from those opposing it. A treaty was signed in 1862 but it reflected the divisions among the Indians of the island: only two chiefs from Wikwemikong were among the signatories. The terms followed those of the Robinson treaties for the upper lakes: Manitoulin and adjacent islands were surrendered to the crown in return for a land grant (100 acres per family) and annuities drawn from the interest upon the capital accumulated from sales of land to white settlers. Indian fishing rights were guaranteed and the Crown Lands Department promised to survey the lands as quickly as possible. However, because of the opposition of the Wikwemikong chiefs the eastern end of Manitoulin Island was excluded from the provisions of the treaty until a majority of the chiefs and principal men of that area agreed to sign. Within a year of the signing of the treaty violence broke out between the Indians from Wikwemikong and government authorities over the rights of whites on Manitoulin Island and over the fishing privileges retained by those Indians who had not signed the 1862 treaty.

Assiginack signed the 1862 treaty, but the opposition of his coreligionists to the stand he took and the divisions between the two Indian communities on Manitoulin Island must have caused him much anguish. A large number of his own people questioned the wisdom of cooperating as he had with a society which seemed determined to force the disappearance of Indian cultural values. One of Assiginack’s own sons, Edowishcosh, was a spokesman for those opposing the 1862 treaty. Assiginack died in 1866 at Manitowaning, but was buried among his coreligionists at Wikwemikong.

Archives of the Archdiocese of Toronto, Macdonell papers, AC07/02–04, AC14/05. PAC, RG 10, vols.116–17, 124–28, 130–39, 273–76, 502–9, 612–15, 621, 691, 792. Canada, Indian treaties and surrenders . . . [from 1680 to 1906] (3v., Ottawa, 1891–1912; repr. Toronto, 1971). Can., Prov. of, Sessional papers, 1863, V, nos.41, 63. Canadian Freeman (Toronto), 20 Nov. 1862. Loyalist narratives from Upper Canada, ed. J. J. Talman (Toronto, 1946). J. G. Shea, History of the Catholic missions among the Indian tribes of the United States, 1529–1854 (New York, 1855). D. B. Smith, “The Mississauga, Peter Jones, and the white man: the Algonkians’ adjustment to the Europeans on the north shore of Lake Ontario to 1860” (unpublished phd thesis, University of Toronto, 1975). Ruth Bleasdale, “Manitowaning: an experiment in Indian settlement,” OH, LXVI (1974), 147–57.

Cite This Article

Douglas Leighton, “ASSIGINACK (Assikinock, Assekinack), JEAN-BAPTISTE (Blackbird),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 12, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/assiginack_jean_baptiste_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/assiginack_jean_baptiste_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Douglas Leighton |

| Title of Article: | ASSIGINACK (Assikinock, Assekinack), JEAN-BAPTISTE (Blackbird) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | March 12, 2026 |