JARVIS, WILLIAM, office holder and militia officer; b. 11 Sept. 1756 in Stamford, Conn., fifth son of Samuel Jarvis and Martha Seymour; m. 12 Dec. 1785 Hannah Peters* in London, England, and they had three sons and four daughters; d. 13 Aug. 1817 in York (Toronto), Upper Canada.

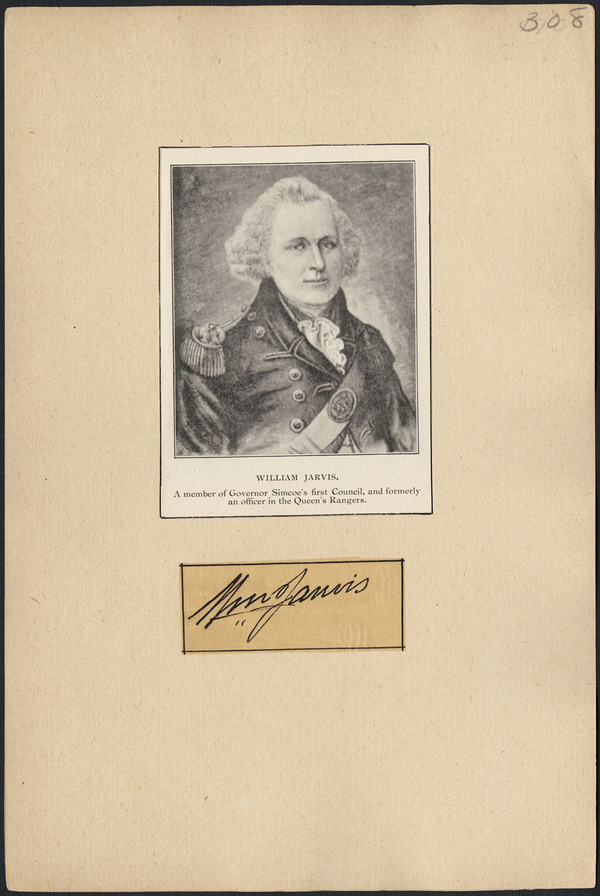

William Jarvis joined John Graves Simcoe’s Queen’s Rangers in 1777. He was wounded at the battle of Spencer’s Tavern in Virginia on 26 June 1781 and was commissioned cornet on 25 Dec. 1782. At the cessation of the American Revolutionary War he went on half pay and returned to Connecticut. There the hostility to the loyalists often resulted in violence, and on one occasion Jarvis was injured. In 1784 or 1785 he travelled to England where he secured Simcoe as a patron. Simcoe recommended him in 1791 to the Home secretary, Henry Dundas, for the positions of provincial secretary and clerk of the Executive Council of the newly established province of Upper Canada. Although Jarvis did not receive the clerkship, he was, however, rewarded with the more important, prestigious, and lucrative post of provincial secretary and registrar. In the summer of 1792 he arrived in Upper Canada as part of Lieutenant Governor Simcoe’s entourage. Soon after he settled in the capital of Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake).

Shortly before leaving England, Jarvis had been chosen provincial grand master of the newly organized Masonic Lodge of Upper Canada. His prominence in local society was reflected by his appointment as deputy lieutenant of the county of York in 1794. Simcoe envisaged the county lieutenants as the core of an indigenous aristocracy and the basis of the local militia [see Hazelton Spencer]. Jarvis maintained his connection with the militia and at his death was a colonel. He was appointed a magistrate in 1800 and from 1801 to 1806 served as chairman of the Court of Quarter Sessions.

From its beginning Jarvis belonged to the province’s tiny governing circle, first at Newark and after 1798 at York. His career was marked by the internecine bickering which characterized this group as its members struggled to consolidate their positions and to secure places for their children. Although Jarvis’s salary was £300, it was supplemented by fees. In 1794 he came into conflict with Attorney General John White* over the division of the lucrative fees on land patents. Jarvis drew up and registered all legal instruments and was responsible for the cost of parchment and wax. White, ever in search of additional income, claimed half of Jarvis’s fees on the grounds that the attorney general was responsible for the crown’s legal matters. He was successful, yet Jarvis still maintained the full burden of expense. Indeed he lost money on each grant processed thereafter and he petitioned in vain for relief until 1815 when he was granted £1,000. His financial problems were not, however, entirely the fault of White or an uncaring Executive Council. At times, changes in land regulations invalidated his work and often he himself was inefficient and careless. In 1800 Lieutenant Governor Peter Hunter discovered that many of the deeds issued by Jarvis contained irregularities such as erasures and corrections, or were drawn up on paper rather than parchment. Hunter censured him and provided strict instructions for the preparation of documents – instructions which by Jarvis’s estimate rendered useless £475 worth of deeds.

Jarvis’s temperament occasioned frequent clashes with his peers. At Newark in 1795 he became involved in a minor cause célèbre over the authorship of a lampoon, purportedly in his hand, maligning several prominent families. Affronted at being suspected, Jarvis challenged four individuals to duels, and even met with one, before Receiver General Peter Russell forced him to swear to keep the peace. Jarvis once confessed to his father-in-law that though he wished to be an executive councillor he “was too proud to ask them [members of the council] to recommend me.” The social tension Jarvis endured within the civil administration can perhaps be understood from Mrs Jarvis’s comment that White and Chief Justice John Elmsley “think an American knows not how to speak.” Jarvis’s sometimes erratic behaviour may have been in part a response to the influence of his vituperative spouse, who once explained her husband’s stalled career by observing that Simcoe was surrounded by “a lot of Pimps, Sycophants and Lyars.”

William Jarvis lived well, if not within his means, on his 100-acre park lot on the outskirts of York. Like so many of the early official families, he sought to ensconce his offspring in the developing society of York and Upper Canada. His eldest son, Samuel Peters Jarvis*, became deputy provincial secretary to Duncan Cameron* in 1827, and later chief superintendent of Indian affairs. Two of his daughters married George* and Alexander* Hamilton, sons of the wealthy Queenston merchant Robert Hamilton, and a third married William Benjamin Robinson*.

William Jarvis was not a central figure in the York élite. Though he contested the riding of Durham, Simcoe, and the East Riding of York against Samuel Heron, Henry Allcock, and John Small* in 1800 and briefly supported Judge Robert Thorpe* in 1806, he was not particularly interested or involved in politics. He was a ranking member of the province’s small administration and his career illustrates some of the problems which plagued the province in its early years.

MTL, William Jarvis papers. PAC, MG 23, HI, 3, vols.1–2. Corr. of Lieut. Governor Simcoe (Cruikshank), 1: 45–47; 2: 288, n.1; 3: 29; 4: 10–11. “Minutes of Court of General Quarter Sessions, Home District,” AO Report, 1932. Town of York, 1793–1815 (Firth), lxxxi. Wallace, Macmillan dict. Burns, “First elite of Toronto,” 289–93. The Jarvis family; or, the descendants of the first settlers of that name in Massachusetts and Long Island, and those who have more recently settled in other parts of the United States and British America, comp. G. A. Jarvis et al. (Hartford, Conn., 1879). W. R. Riddell, The life of John Graves Simcoe, first lieutenant-governor of the province of Upper Canada, 1792–96 (Toronto, [1926]), 453–54. G. C. Patterson, “Land settlement in Upper Canada, 1783–1840,” AO Report, 1920: 52–53, 82–83, 90–91, 117–18.

Cite This Article

Robert J. Burns, “JARVIS, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jarvis_william_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jarvis_william_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert J. Burns |

| Title of Article: | JARVIS, WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |