Source: Link

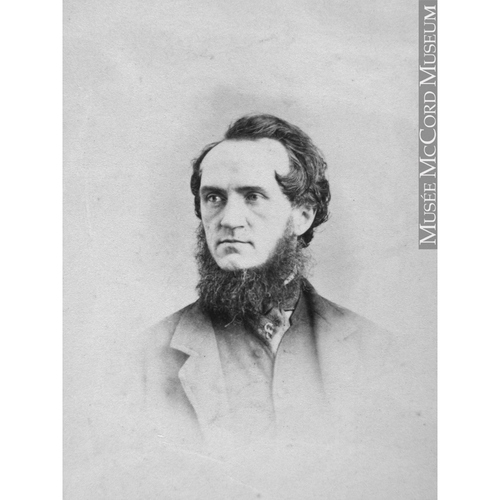

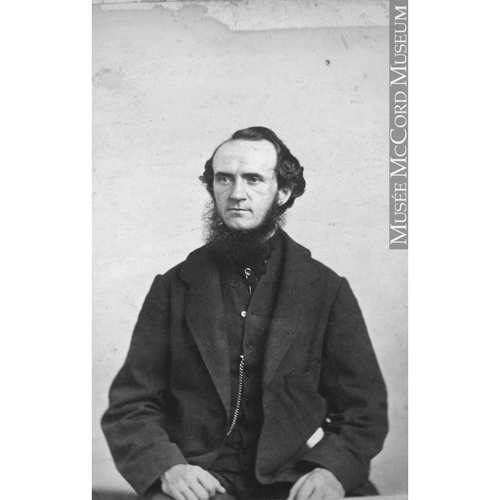

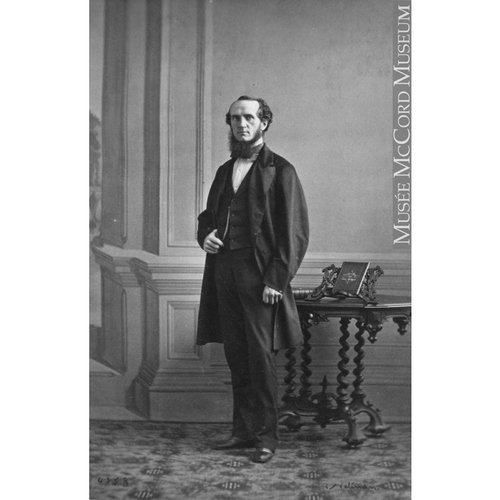

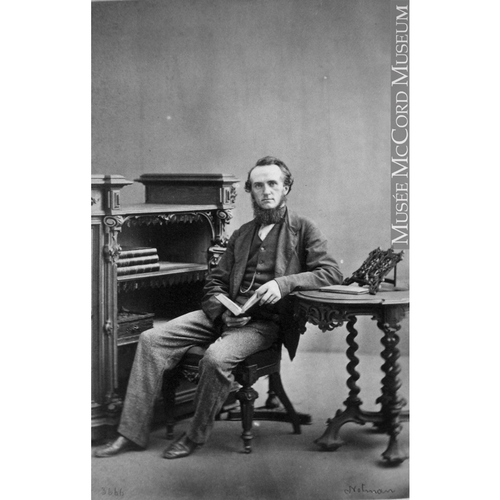

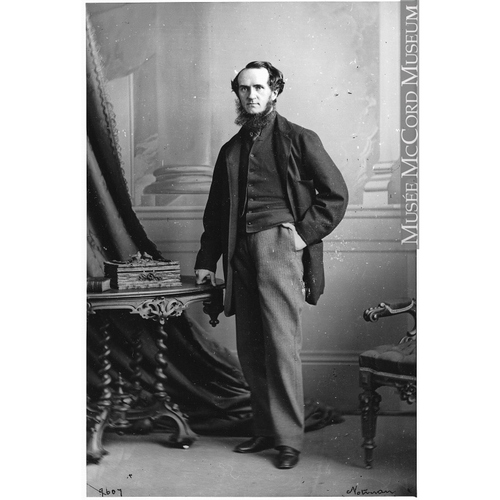

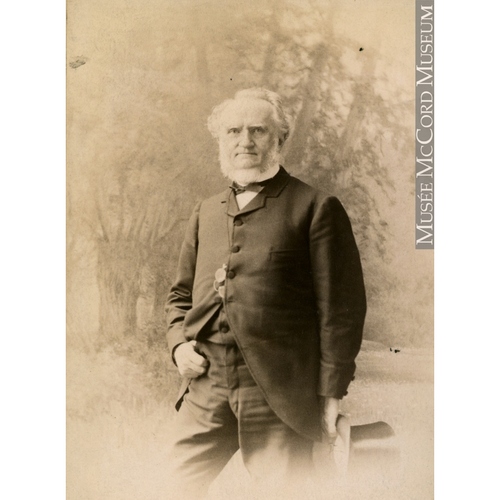

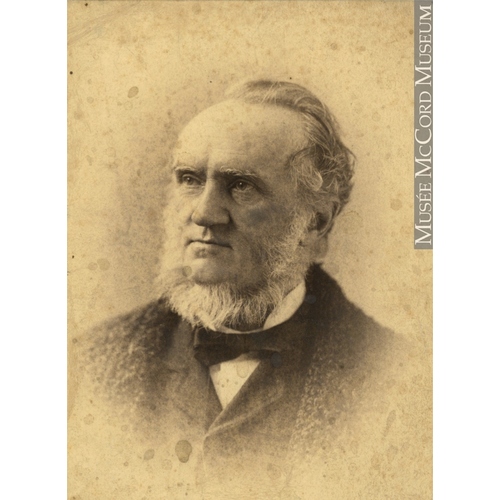

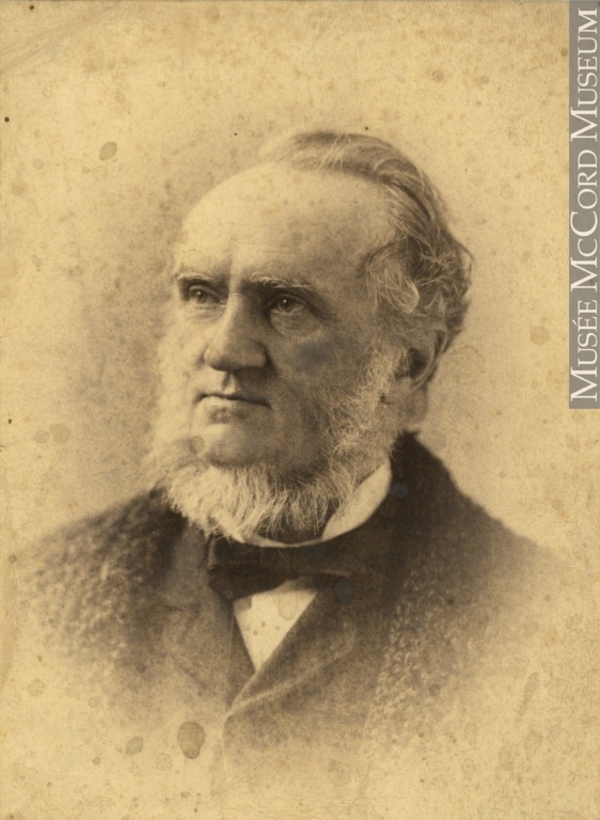

NOTMAN, WILLIAM, photographer and businessman; b. 8 March 1826 in Paisley, Scotland, first child of William Notman and Janet Sloan; d. 25 Nov. 1891 in Montreal.

William Notman was born into an educated, industrious, and ambitious family, which, at a time of general upward mobility in the Scottish rural classes, had risen in two generations from the ranks of farmers, miners, and millworkers to the level of the urban commercial and professional bourgeoisie. His grandfather had been a dairy farmer; in 1840 his father, a designer and manufacturer of Paisley shawls, moved from the large town of Paisley to Glasgow and worked as a commission agent before establishing a wholesale woollen cloth business. Able to obtain a good education, William studied art with a view to making it his career, but he was persuaded instead to enter the family business, which, it was felt, would offer him more security. He worked first as a travelling salesman and then became a junior partner about 1851. On 15 June 1853 he married Alice Merry Woodwark in the Anglican church at King’s Stanley, England. They settled in Glasgow, soon had a daughter, and looked forward to a comfortable future. By the mid 1850s, however, Scotland was in the grip of a depression, and William Notman and Company slid into bankruptcy. Aspects of the failure did not reflect well on Notman, and he found it expedient to emigrate to Lower Canada.

Shortly after arriving in Montreal, Notman found employment with Ogilvy and Lewis, a wholesale dry goods firm, and in November 1856 his wife and child joined him. With the onset of the winter slack season, he obtained leave of absence to start a photographic business. He had grown up during the period of the discovery and development of the earliest photographic techniques (Nicephore Niépce had produced the first permanent photographic image in the year of Notman’s birth), and he had practised photography as an amateur in Scotland. By late December 1856 his business was in operation; shortly after, he was obliged to hire assistants. Within three years his parents, a sister, and his three brothers had joined him in Montreal.

Notman’s first important commission was from the Grand Trunk Railway in 1858 to photograph construction of its Victoria Bridge at Montreal, considered an engineering marvel [see James Hodges*]. Over the next two years Notman produced photographs and stereographs of all phases of its construction, and their quality, along with the importance of the bridge, earned him an international reputation. When the Prince of Wales visited Montreal in August 1860, Notman, at the request of the Canadian government, prepared its gift of a portfolio of photographs in two gilt-trimmed, leather-bound covers, enclosed in a silver-mounted bird’s-eye maple box. According to family tradition, Queen Victoria was so pleased with it that she proclaimed Notman “Photographer to the Queen.” Notman first used this designation in an advertisement in the Montreal Pilot of 14 Dec. 1860 – and displayed a duplicate of the maple box to demonstrate to visitors the elaborateness of the gift.

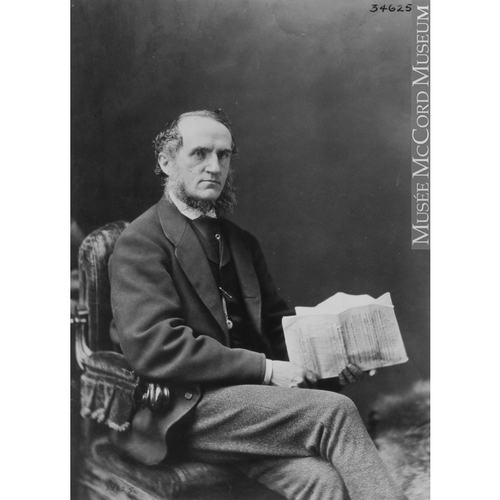

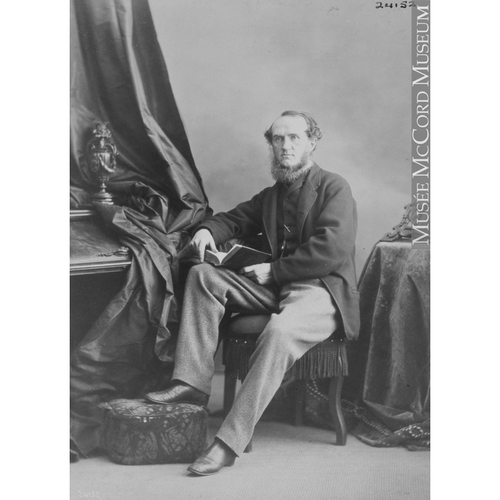

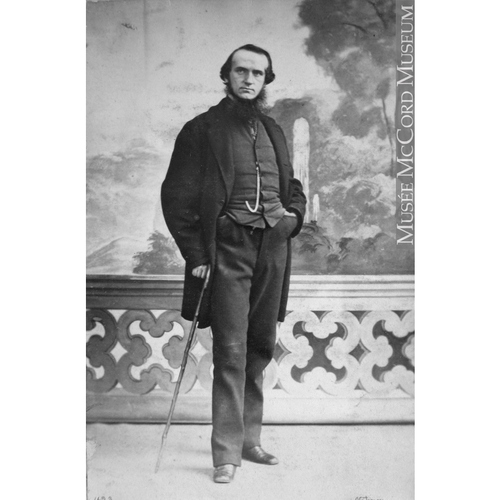

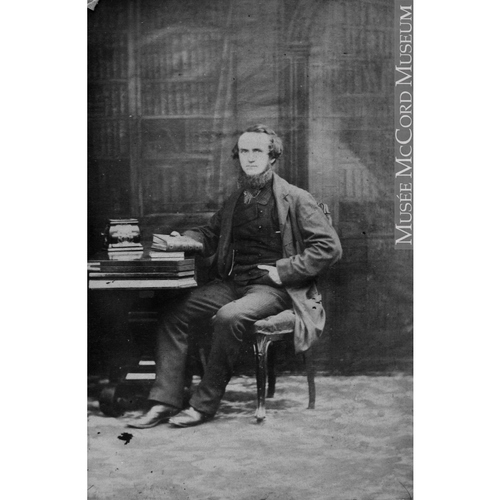

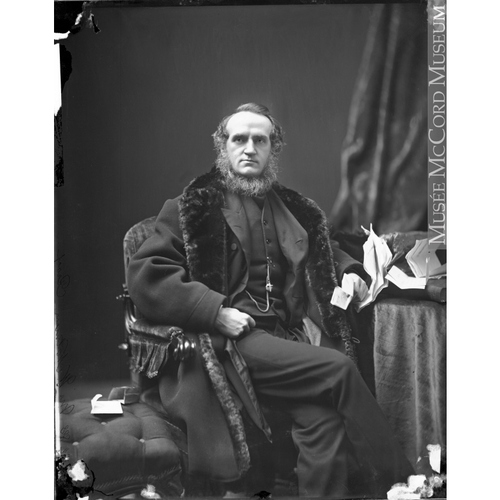

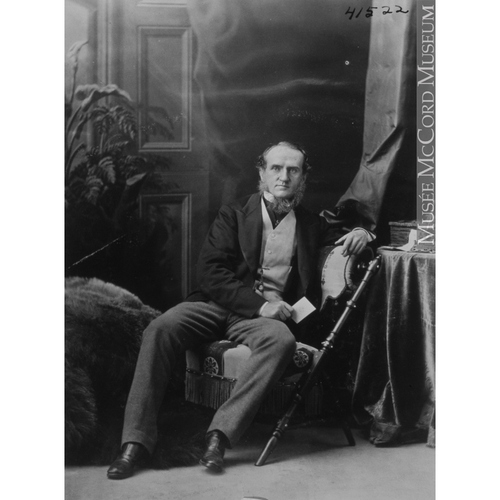

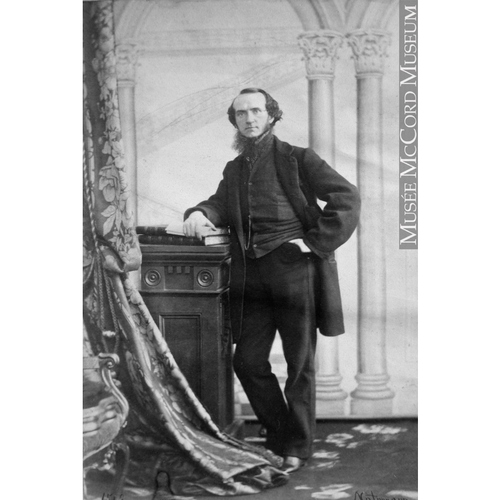

Notman’s business sense was, indeed, a fundamental ingredient in his formula for success. Portrait work was the bread and butter of his trade, and the competitiveness of his prices as well as the variety of poses and services he offered drew customers from all economic stations. Middle- and lower-class French Canadians tended to prefer French Canadian studios, however, even though many of Notman’s photographers were francophones. The cream of Notman’s business was provided by services of a luxurious nature; as early as 1857, for example, he offered life-sized enlargements of portraits, coloured in oil or water-colours and displayed in ornate gold frames. His growing reputation as a portraitist eventually attracted almost all the notables of Canada, French- and English-speaking, to his studio, and visitors from overseas and the United States sought him out. Among his subjects were Sir John A. Macdonald and Louis-Joseph Papineau*, bishops Francis Fulford* and Ignace Bourget*, Prince Arthur* and Sir Donald Alexander Smith*, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Harriet Elizabeth Beecher Stowe, Sitting Bull [Ta-tanka I-yotank*] and Buffalo Bill [William Frederick Cody].

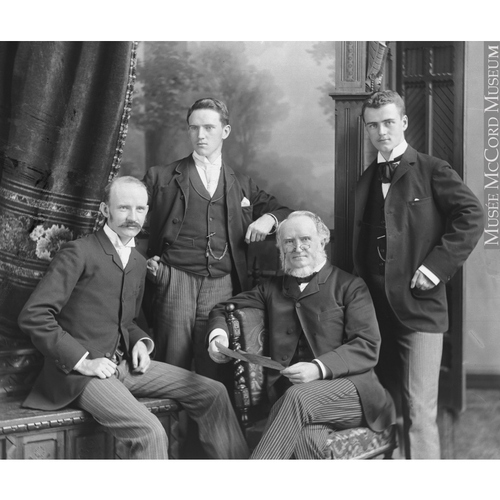

In addition to individual portraits, Notman produced group portraits of athletic clubs, social gatherings, and prominent families. Set in an appropriate background, these portraits were composite photographs put together under Notman’s direction by a staff of photographers and painters. The composites were produced by photographing each person in the studio, cutting the figures out of the prints, and then pasting them on a painted background. Copies were made for sale in various standard sizes. Because even the tiniest figures in the group came out as high quality portraits, Notman could confidently expect to make at least one sale to every person in the picture, and many photographs depicting major sports or social events were bought by the general public as souvenirs. The immense size of some of the scenes and the great number of people who appeared in them – often as many as 300 – combined to attract wide attention.

Notman also became well known for his photographs of Canadian scenes and life. From the beginning he and his photographers compiled a large stock of negatives loosely catalogued as “views.” His relentless pursuit of images to add to the files eventually led him or his photographers to cross the new country from coast to coast, training their cameras on the land and the activities it generated, including lumbering, mining, hunting, and farming; on the rivers and seas and the vessels that fished or plied them; on the cities, growing in the east or mushrooming in the west, and the industry, trade, and business that supported them; on the resorts and hotels in the major holiday centres; on the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, which, with other railways, bound all these environments into a whole; and on the people who made up the country from prairie Indians to Montreal magnates. In Montreal he photographed pedlars, newsboys, woodcutters, and other humble members of the Montreal street fraternity. These photographs were produced in the studio using props and painted backgrounds so as to make them appear to have been taken outdoors. The same techniques were applied in the creation of series on caribou and moose hunting featuring Colonel James Rhodes and his Indian guides.

The great variety of “views” that Notman offered in an age when amateur photography was severely limited, and the moderate prices he charged, ensured that his photographs would be attractive to anyone wishing to record visits or illustrate to others the merits of their locality. As well, he ensured availability in various forms, including albums and stereographs, and in many locations, such as his studio, stationery and book stores, all major Canadian hotels, the transcontinental trains, and every large railway station in the country.

Notman’s success was due only in part, however, to his initiative, resourcefulness, and aggressiveness as a businessman. His artistic talent gave him a product of superior quality to sell, and his readiness to experiment and introduce new techniques and ideas kept him in the forefront of a highly competitive field. In 1860 and 1869, for example, he photographed solar eclipses for Professor Charles Smallwood* of the McGill Observatory, the photographs of 1869 serving to illustrate an article by Smallwood in the Canadian Naturalist (Montreal). In the winter of 1864–65 he adopted the magnesium flare as an artificial source of illumination, a technique that had been introduced in England only shortly before. He also led in the introduction of cabinet-sized photographs in North America.

Notman owed some of his success to the quality of the painters he hired, for their work was often an integral part of the final product. He was employing William Raphael* on commission before 1860, but, dissatisfied with Raphael’s work, he engaged John Arthur Fraser that year to head a new art department, created to colour photographs, retouch negatives, and paint studio backgrounds. To assist Fraser, 18-year-old Henry Sandham* was hired, and the art department eventually attained impressive proportions.

His personal and professional interest in art led Notman to establish relations with Montreal’s most prominent painters. Several of them, Fraser, Sandham, Otto Reinhold Jacobi*, Charles Jones Way, and Robert Stuart Duncanson*, along with Cornelius Krieghoff*, were represented in Notman’s first book, Photographic selections. Published in 1863 “to foster the increasingly growing taste for works of art in Canada,” it was composed of 44 photographs of paintings, most by old masters, and two views from nature. Two years later Notman published a second volume, containing 11 photographs from nature and a greater number of photographic reproductions of contemporary Canadian paintings. Meanwhile, in 1864 he had published North American scenery, composed entirely of photographic reproductions of landscapes by Way. And while Notman was reproducing works of the painters, at least two painters, Jacobi and Krieghoff, were using Notman photographs as the basis for some of their works.

Notman also fostered the development of painters and other artists in his city through his support of the Art Association of Montreal, established in January 1860. Not only was Notman a charter member but the formative meeting was held in his studio. He lent canvases from his growing private collection to be shown at the association’s conversaziones and provided photographs as prizes. Anxious that a permanent gallery be obtained for the association, he offered as a gift to it a life-sized painted photograph of Bishop Fulford if, within five years, a building was acquired in which to display it. Meanwhile his studio was, as it had been in the past, the centre of the Montreal art community and a gathering point for visiting artists. In his huge reception room Notman held numerous exhibitions of painting and sculpture; the best known artists of the day, including Napoléon Bourassa* and Robert Harris*, frequented it. There in 1867 the Society of Canadian Artists was formed, three Notman painters (Fraser, his brother William Lewis Fraser, and Sandham) being among the charter members. Not until 1878, however, was a permanent art gallery, specially designed for the purpose, constructed; Notman had chaired the building committee. From 1878 to 1882 he also acted as a councillor to the Art Association of Montreal.

In addition to the books on works of art, Notman published the highly popular Portraits of British Americans, with biographical sketches, produced from 1865 to 1868 in collaboration with John Fennings Taylor*. In 1866, discerning a heightened interest in sports as a leisure activity [see William George Beers], Notman published three portfolios of photographs entitled Cariboo hunting, Moose hunting, and Sports pastimes and pursuits in Canada. Although he did not publish books after 1868, photographs from his studio illustrated other publications such as Henry George Vennor*’s Our birds of prey (1876). In 1869 a half-tone reproduction of a Notman photograph of Prince Arthur in George-Édouard Desbarat’s Canadian Illustrated News constituted the first commercial use of this technique. It demonstrated once again Notman’s place in the forefront of photography.

By the mid 1860s Notman had 35 employees in his Montreal studio, including photographers and painters, their apprentices and assistants, bookkeepers and clerks, receptionists and secretaries, dressing-room attendants, and printing, dark-room, and finishing personnel. Before the end of the decade his work was in such demand that he decided to expand. In the spring of 1868 he opened a branch studio in Ottawa, the capital of the new confederation, under the management of young William James Topley*, who had been apprenticed to him for three years. Later that year a Toronto studio was launched under the name of Notman and Fraser, John Arthur Fraser having been taken into partnership and given management of the studio to avoid his leaving the fold. Fraser maintained the Notman tradition of artistic excellence, employing for a time the budding painters Horatio Walker*, Homer Ransford Watson*, and Frederick Arthur Verner, among others; in 1880, however, he left Notman to embark on a successful career in painting. Notman studios were opened as well in Halifax in 1870 and in Saint John, N.B., two years later, and during the 1880s he operated at least 20 studios, seven of which were in Canada. Seasonal studios at Yale College and Harvard University catered to the student trade.

Notman had been making inroads into the American market since 1869 when he had received the contract to photograph the staff and students of Vassar College. He was a regular contributor to the influential Philadelphia Photographer, edited by Edward Wilson, an admirer of his work, who often featured Notman’s art, innovative methods, and Montreal studio. In 1876 Notman astutely joined Wilson in forming the Centennial Photographic Company to obtain the monopoly on photographs taken at the Philadelphia Centennial International Exhibition that year; the company, which employed Fraser as art superintendent, had a staff of 100 housed in a large building on the grounds. Notman also participated in the exhibition through a display of his studios’ photographs; they won a gold medal from the British judges. Notman photographs had already earned medals at exhibitions in Montreal in 1860, London in 1862, and Paris five years later, and would earn others in Australia in 1877, Paris again the following year, and London in 1886.

Meanwhile, in Montreal the studio had continued to grow until in 1874 it employed a staff of 55. During the mid 1870s it alone produced some 14,000 negatives a year. In 1877, in order not to lose Sandham, Notman made him a partner in the Montreal firm, which was renamed Notman and Sandham. By 1882, however, the painter had left to pursue a career in the United States. A decline in business, possibly a delayed consequence of difficult economic conditions in the 1870s, was reflected at the end of that decade and in the early 1880s in a decrease in staff, which reached a low of 25 in 1886 before climbing back to 38 by 1892.

In addition to making and selling photographs Notman gave instruction to beginning photographers. How extensive his courses were is unknown, but his influence as a teacher becomes clear when it is realized that all the managers and photographers in his divers studios served their apprenticeship under him. During his 35-year career as many as 40 photographers were on the Montreal payroll alone, and a large number of these later successfully operated their own studios.

The management of Notman’s enterprise would have overwhelmed the average man. Supervising a numerous staff, nurturing budding artistic talents, keeping abreast of technological and artistic developments, planning transcontinental trips, devising new ventures, signing contracts, and still keeping his own photographic talents finely tuned must have taxed the ingenuity, strength, and humour even of this dynamic man. Yet Notman carried on other activities and contributed particularly to the development of his adopted community. He was active in real estate and held part-ownership of some 295 lots in Longueuil; most were auctioned off in June 1873. He was part of the syndicate that built the luxurious Windsor Hotel, opened in February 1878. For many years he was a member of the Longueuil Yacht Club, of which he was president in the 1870s. An ardent yachtsman, he furthered interest in the sport by offering the “Notman Cup” as a prize at local meets. He also promoted rowing by bringing in outstanding crews to provide high-calibre competition. Originally members of Zion (Congregational) Church, Notman and his family joined St. Martin’s (Anglican) Church in Montreal in 1868 and attended St. Mark’s Church, Longueuil, when they resided there during the 1870s; Notman served as minister’s warden at St. Mark’s for several years and was a financial pillar. He was a governor of the Montreal General Hospital in the 1880s at least and a member of the Young Men’s Christian Association.

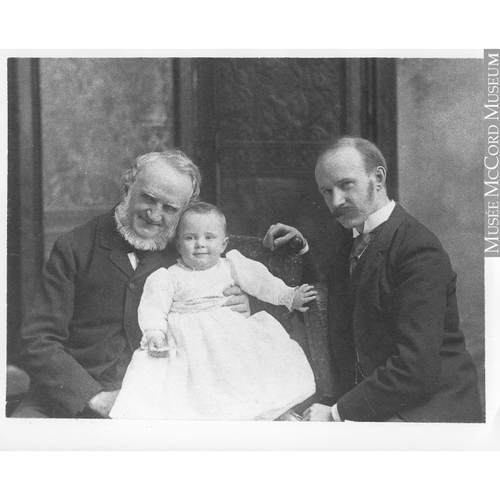

The Notmans had seven children, and all three boys worked in their father’s business, where they had trained as photographers. One, William McFarlane, became a junior partner in William Notman and Son in 1882 following Sandham’s departure. Notman’s brothers as well as some of his nieces and nephews were all on staff at one time or another. William himself continued to be active as a photographer until his death, from pneumonia, on 25 Nov. 1891. He had always paid close attention to his firm and he invariably refused to rest, even after a cold, which ultimately proved fatal, had begun to progress rapidly. A contemporary described him shortly after his death as a man “singularly modest and unobtrusive,” thoughtful and deliberate, “well informed of the events of the day, and quick to note their trend,” decided and “even tenacious” in his opinions. Two sons carried on the firm, William McFarlane from 1891 until his death in 1913 and Charles Frederick from 1894 until 1935, when he sold the business to Associated Screen News.

Notman’s personal authorship of photographs produced by his studio is rarely documented, but whenever it is the same style is evident, characterized by simplicity and economy, tending to starkness in some cases and even to abstraction in others. Notman had the ability to extract the essence of his subject through his choice of viewpoint, light, and line, and he was able simultaneously to describe it accurately and to provoke in the viewer an emotional response to it. As a portraitist, Notman, because of his attraction to the monumentality of form and his mastery of line, light, and composition, imbued his most prominent subjects with heroic – not to say mythic – qualities in tune with the nationalistic fervour that embraced the new country of Canada. On the other hand, because Notman photographs also accented realism and authenticity of dress or equipment, they constitute a valuable social record.

The production of Notman’s studios, however, is of historical value for reasons more fundamental than authenticity of detail. Notman had an insatiable appetite for learning, recording, and expressing. His photographs document almost the entire range of activities in late Victorian Canada, and he gathered together the most talented photographers and painters available in order to do so more effectively than he could have done alone. Furthermore, he gave his photographers and painters a freedom within broad limits that enabled them to express their reaction to what they saw in such a manner that their production reflects their own style while bearing his distinctive mark. Since many went on to become prominent, Notman was instrumental not only in recording and expressing the essence of his era but also in forming others who could do so effectively through their art.

Notman took all of Canada as a subject worthy of his cameras. Through the establishment of relatively autonomous regional studios, he was largely able to avoid imposing on the rest of Canada the view from Montreal. Nevertheless, his personal vision was centred on that city, which was, in truth, the heart of the country. Even Vancouver, the “end of the track,” was linked directly to it through the builders of the CPR, and almost every place in between was tied to it at least indirectly. Notman’s Montreal reflected the transitional nature of a land and a people poised at the watershed between the 19th and 20th centuries, ready, as Sir Wilfrid Laurier* fondly believed, to assume the mantle of a great power. Notman expressed imperial Montreal through his portraits of its great men – whose reputations were international – and photographs of imposing buildings. He depicted the local city through his portraits of average Victorian Montrealers, often conducting their ordinary business. In the harbour he caught squat, steam-driven vessels being loaded beside majestic, wooden sailing ships. And beyond the city his photographers captured labourers dwarfed by the Rockies in scenes symbolic of the immense task that Canada – led by Montreal – had given itself, that of harnessing to an industrial and trading economy the potential in natural resources of half a continent.

Among William Notman’s publications are Photographic selections (Montreal, 1863), North American scenery . . . 1863–64 (Montreal, [ 1864]), and, in collaboration with John Fennings Taylor, Portraits of British Americans, with biographical sketches (3v., Montreal, 1865–68). The McCord Museum, Notman Photographic Arch., holds an important collection of his photographs, some of which have been reproduced in S. G. Triggs, William Notman: the stamp of a studio (Toronto, 1985).

ANQ-Q, P-530. Gloucestershire Record Office (Gloucester, Eng.), King’s Stanley, Reg. of baptisms, 15 June 1853. Portrait of a period: a collection of Notman photographs, 1856–1915, intro. E. A. Collard, ed. J. R. Harper and S. G. Triggs (Montreal, 1967). Reid, “Our own country Canada”.

Cite This Article

Stanley G. Triggs, “NOTMAN, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/notman_william_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/notman_william_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Stanley G. Triggs |

| Title of Article: | NOTMAN, WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | March 31, 2025 |