As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

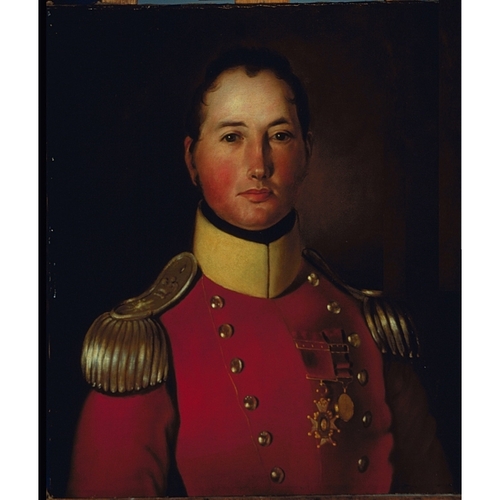

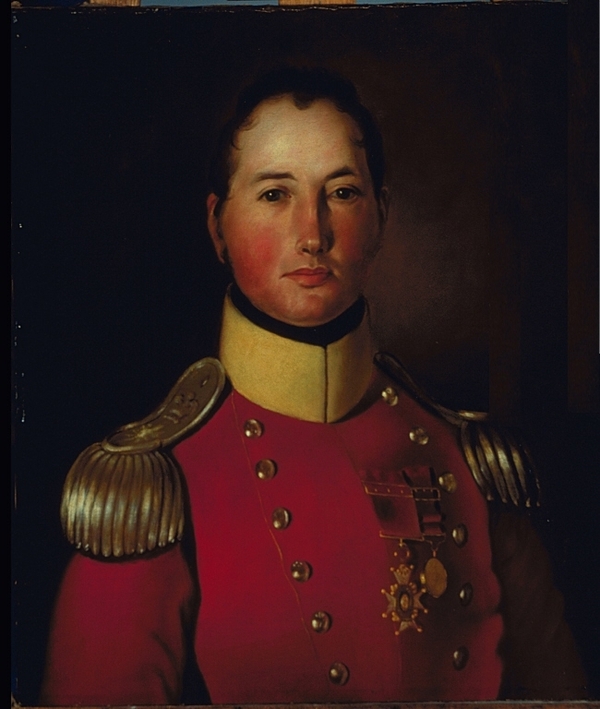

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

MORRISON, JOSEPH WANTON, army officer; b. 4 May 1783 in New York City, only son of John Morrison, deputy commissary general in North America, and Mary Wanton, who died two days later; m. 25 April 1809 Elizabeth Hester Marriott, daughter of the late Randolph Marriott of Worcester, England, and they had no children; d. 15 Feb. 1826 at sea.

Joseph Wanton Morrison entered the army as an ensign in the 83rd Foot in 1793 and was promoted to a lieutenancy in the 84th Foot the following year. However, at his young age he did not actually join either unit but was removed to an independent company and placed on half pay. His active career began in 1799 when he was appointed to the 17th Foot, serving with the 2nd battalion in the Netherlands, where he was wounded in the action at Egmond aan Zee on 2 Oct. 1799 [see Sir Isaac Brock*]. The regiment had returned to England by the end of November, and from April 1800 he was listed as one of its captains. The next month the 17th arrived on Minorca, where Morrison commanded a company on garrison duty until the Treaty of Amiens. After repatriation to Ireland in August 1802, the 2nd battalion was disbanded. He then received a brevet majority and was placed on the Irish half-pay list.

In 1804, following the renewal of hostilities between Britain and France, Morrison was appointed an inspecting officer of yeomanry in Ireland, and he transferred to the 2nd battalion, 89th Foot, in June 1805. In November 1809 he was promoted lieutenant-colonel in the 1st West India Regiment and immediately joined it in Trinidad. In July 1811 he exchanged back to the 89th Foot and the next year took the 2nd battalion to Halifax, arriving on 13 Oct. 1812. After wintering there, the battalion reached Quebec on 15 June 1813 and 19 days later marched to Kingston, Upper Canada. There Morrison spent the summer serving on courts martial, doing general garrison duties, and drilling his battalion, which was considered for an attack on Fort Niagara (near Youngstown), N.Y.

In the fall of 1813 American forces launched a two-pronged attack on Montreal. Major-General Wade Hampton advanced down the Chateauguay River from the south to meet Major-General James Wilkinson and Commodore Isaac Chauncey, who were moving down the St Lawrence from Sackets Harbor, N.Y. The threat prompted the commander-in-chief, Sir George Prevost*, to give Morrison his first field command, over a “corps of observation,” with orders to follow Wilkinson as he descended the St Lawrence and to hinder his progress if possible. This was not an easy assignment because the invaders greatly outnumbered the British and colonial defenders. None the less, annoyed with Morrison’s harassment, Wilkinson ordered Brigadier-General John Parker Boyd to land and defeat the pesky little British force nipping at their heels.

Unfortunately for the Americans, Morrison was able to fight the battle on ground of his own choosing, some 25 miles west of Cornwall – an essentially open stretch of about 700 yards on the property of John Crysler* between a wood and the river, from where he was supported by Commander William Howe Mulcaster’s flotilla of gunboats, which had been accompanying him. Morrison was able to utilize the experience and discipline of his regulars by enticing the Americans into a set-piece battle in the European tradition. The individual sharpshooters of the enemy, who performed best when there was an abundance of cover, were at a disadvantage. Consequently, despite its own considerable losses, Morrison’s “corps of observation” was able to inflict a stinging tactical defeat on Boyd’s detachment, which outnumbered it by almost five to one. Combined with the reverse Hampton had suffered at Châteauguay 17 days earlier [see Charles-Michel d’Irumberry de Salaberry], as well as the hesitancy and lack of accord among the American commanders, Morrison’s victory of 11 November saved Montreal from attack that year. For his part Morrison received a gold medal, a sword from the merchants of Liverpool, England, and the thanks of the House of Assembly of Lower Canada.

Following the victory at Crysler’s Farm, as the battle became known, Morrison served at Quebec, Montreal, Cornwall, Coteau-du-Lac, where he commanded the garrison and had charge of communications on that part of the St Lawrence, and Fort Wellington. It was from this last place that he and his battalion were ordered to proceed to Kingston at the end of June 1814 on the first stage of a journey that took them to the Niagara frontier in time for the battle of Lundy’s Lane. At this action on 25 July Morrison and the 89th formed a key part of the centre of the defensive line as Lieutenant-General Gordon Drummond*’s troops successfully held the crest of the hill. Like the rest of the British force that day, the 89th performed brilliantly under a series of blistering American attacks. The lieutenant-colonel himself was wounded, “severely, not dangerously.”

Although Morrison’s wound forced him from the battlefield, it did not seriously incapacitate him. He remained with his battalion in the Canadas and in December 1814 sat as a member of Major-General Henry Procter’s court martial in Montreal. The next year he returned with his battalion to Britain. However, in 1816 his wound had not healed enough to permit his joining the 1st battalion of his regiment in India and in April he went on half pay. On 12 Aug. 1819 Morrison received the brevet of colonel and in April 1821 returned to full-time service as a lieutenant-colonel in the 44th Foot, then in Ireland.

In June 1822 Morrison embarked with the 44th for India, arriving at Calcutta in November. From July 1823 he was with the 44th in Dinapore before returning to Calcutta. In July 1824 he was appointed brigadier-general with command of the southeastern division of the forces in India. It was in this capacity that he led the successful, though extremely unhealthy, expedition to Arakan against the Burmese. Like many of his men, Morrison took sick in this malarial area and, anticipating that a sea voyage would restore his health, decided to return home. Unfortunately, this brilliant officer, whose every command had been a success, “died at sea, on board the Cara Brea Castle on the 15th February, 1826.”

Nothing is known of Morrison’s private life and character. However, his army service illustrates how careful cultivation of a career by a zealous and capable officer could bring personal success and military glory. At his death it was regretted that the nation had prematurely lost the services of a good senior officer who was just beginning to realize his potential. With only brief stops in each, he had made important contributions to several parts of the empire, including the Canadas.

PAC, RG 8, I (C ser.), 167: 21; 232: 142; 363: 87–92; 679: 480; 681–84; 1171; 1172: 54; 1203 1/2H: 89; 1203 1/2J: 125; 1203 1/2K: 5, 56; 1203 1/2L: 154, 171; 1203 1/2R: 41, 95; 1222. Annual reg. (London), 1799–1827. Doc. hist. of campaign upon Niagara frontier (Cruikshank). Select British docs. of War of 1812 (Wood). G.B., WO, Army list, 1793–1827. H. J. Morgan, Sketches of celebrated Canadians. J. W. Fortescue, A history of the British army (13v. in 14, London, 1899–1930), 9–11. Historical record of the Forty-Fourth, or the East Essex Regiment, comp. Thomas Carter (2nd ed., Chatham, Eng., 1887). Hitsman, Incredible War of 1812. G. F. G. Stanley, The War of 1812: land operations ([Toronto], 1983).

Cite This Article

Carl Christie, “MORRISON, JOSEPH WANTON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/morrison_joseph_wanton_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/morrison_joseph_wanton_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | Carl Christie |

| Title of Article: | MORRISON, JOSEPH WANTON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1987 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |