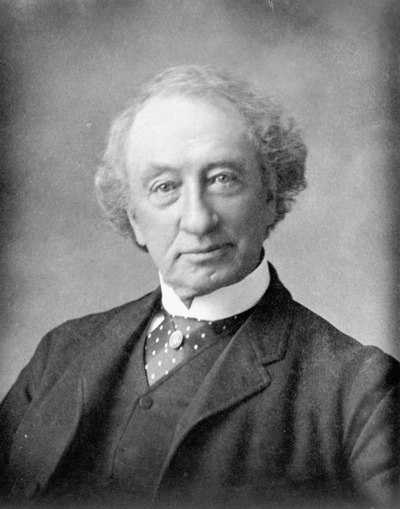

Sir John A. Macdonald

Introduction

A master of the art of compromise and a brilliant tactical politician, Sir John A. Macdonald played a pivotal role in the formation, consolidation, and expansion of the Canadian confederation. His career generated – and continues to generate – considerable controversy. Macdonald has been revered as “the man who made Canada” by author Richard Gwyn (in John A.: the man who made us, the life and times of John A. Macdonald, the first volume of his two-part series, published in Toronto in 2007) and reviled as an instigator of the “ethnic cleansing and genocide” of aboriginal peoples by Professor James Daschuk (in “When Canada used hunger to clear the west,” Globe and Mail, 19 July 2013).

Drawing mostly on biographies of Macdonald and his contemporaries that were written for the Dictionary of Canadian Biography/Dictionnaire biographique du Canada during the 1980s, this collection examines the relationship between his political career and the broad issues facing British North America during the 19th century.

We begin with perspectives on his personality, his troubled family life, and his reputation as a serious drinker. Only his second wife, Susan Agnes Bernard (Macdonald), could control him when he was drinking, and even she could not always cope. In Kingston, Upper Canada (Canada West; present-day Ontario), Macdonald became a successful lawyer, and in 1844, at the age of 29, he was elected to the legislature of the Province of Canada. Three years later he became a cabinet minister in the governments headed by William Henry Draper and Henry Sherwood, and from 1854 to 1867 (with brief pauses in 1858 and 1862–64) he served as attorney general for Canada West. By 1856 he had become the leader of the Canada West section of the government.

Macdonald was a pragmatic politician, eschewing abstract principles and adapting to changing circumstances. A member of the Orange order, he nevertheless supported separate schools for Roman Catholics in Canada West. Initially an opponent of responsible government, he quickly accepted the new reality and established an effective alliance with George-Étienne Cartier and the Bleus in Canada East (Lower Canada; present-day Quebec).

The focus of this collection of biographies then shifts to the connection of the North American colonies with Great Britain, their relationship with the United States, and what proved to be the political response: confederation. Macdonald held that Canada must maintain its close connection with Great Britain, and that constitutional traditions were the best guarantee of individual liberty. Although he believed that a legislative union was the best protection against the United States, he agreed to form a coalition with Reform leader George Brown to seek a federal solution to Canada’s political problems. Macdonald played a key role in the Charlottetown and Quebec conferences of 1864. According to Thomas D’Arcy McGee, he was responsible for 50 of the 72 resolutions at the Quebec conference that established the constitutional framework for confederation.

As prime minister of the new dominion from 1867 to 1873, and again from 1878 until his death in 1891, Macdonald exerted enormous influence on its political and economic development. Under his leadership, Canada acquired Rupert’s Land, and thus ensured that the northwest would not fall into the hands of the United States. But in the Red River colony, Canadian expansion produced a conflict in 1869–70 with the Métis, headed by Louis Riel, over land rights. Although Macdonald initially failed to grasp the seriousness of the situation, he and Cartier would incorporate some of Riel’s demands into the act that brought Manitoba into confederation in 1870. Fifteen years later, similar issues related to land surveys and titles, exacerbated by conditions of near-starvation on aboriginal reserves, lay behind the North-West rebellion in what would become, in 1905, the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. Nine leaders were executed: eight aboriginals, including Wandering Spirit, and Louis Riel. Despite pressure from French Canada, Macdonald refused to commute Riel’s sentence – a decision that damaged the Quebec branch of the Conservative Party, and paved the way for the rise of Honoré Mercier’s Parti National. Macdonald’s reputation in Quebec was weakened further by his refusal in 1890 to use the federal power to protect separate schools in Manitoba [see Thomas Greenway].

Central to Macdonald’s vision for Canada was what became known as his National Policy. Protective tariffs would safeguard Canada from the economic power of the United States, and a transcontinental railway would strengthen the east–west connection, bring British Columbia into confederation, ensure economic modernization, and promote settlement in the North-West Territories (present-day Saskatchewan and Alberta). The policy largely succeeded in its aims, but it was also associated with the Pacific Scandal that brought down Macdonald’s government in 1873, with immigration policies that excluded the Chinese from the vote, and with the use of hunger to force aboriginal peoples onto reserves and thus clear the way for the railway’s construction.

Finally, there is an exploration of Macdonald’s hold on power. Like all other political groups, the Conservatives attempted to strengthen their grip on the government and the country by influencing the press and pulling the wires of patronage. Macdonald, as their leader, managed contentious policies and fractious followers, worked closely with allies in Quebec, and dealt with enemies in other parties. He was still prime minister when he died in 1891, and the “Old Man” of the Conservative Party was mourned by its supporters across the nation he helped to create.

We invite you to read about the different perspectives on Macdonald that appear in our biographies, and to form your own judgement of the man and his world.