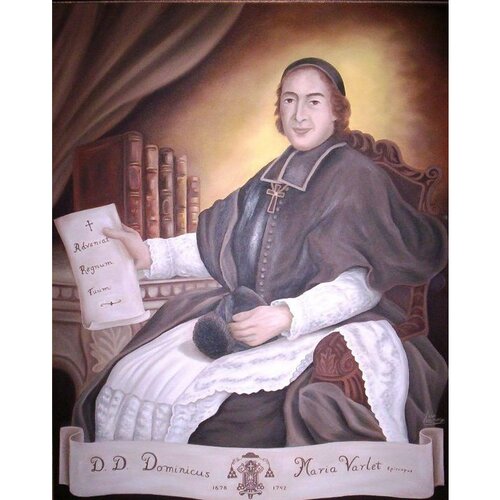

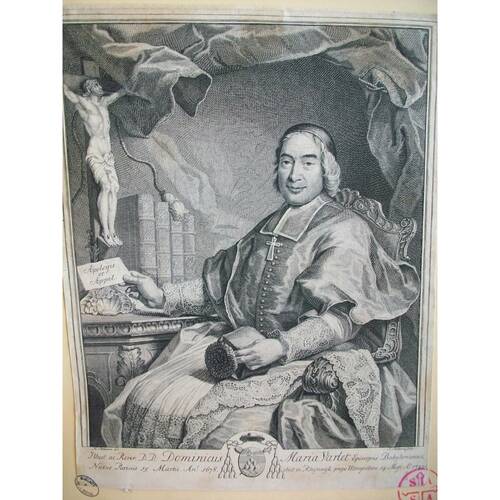

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

VARLET, DOMINIQUE-MARIE, priest, missionary, vicar general, bishop of Babylon; b. 15 March 1678 in Paris, son of Achille Varlet, Sieur de Verneuil, and Marie Vallée; d. at Rijnwijk (Zeist, Neth.), 14 May 1742.

Dominique-Marie Varlet was the son of an actor. His father, known under the name of Sieur de Verneuil, and his uncle, Charles Varlet, the famous La Grange, collaborator and friend of Molière, had won renown on various Parisian stages before becoming members of the Comédie-Française at its creation in 1680. Little is known about his mother other than that she was the daughter of a Parisian hatter, that she too had been in the theatre, and that she was much younger than her husband. The Varlets had had seven children, only three of whom reached adulthood: Jean-Achille, born in 1681, who died, an attorney in the parlement of Paris, in 1720; Marie-Anne, the youngest of the family, who was married to Antoine Olivier, an attorney at the Châtelet; and Dominique-Marie.

The latter had early been destined, it seems, to the ecclesiastical state. He was enrolled in the Séminaire de Saint-Magloire in Paris, which was run by the Oratorians, then in the Collège de Navarre (one of the colleges in the University of Paris), studying in succession for the baccalauréat (1701), licentiate, and doctorate in theology (1706). It was at Saint-Magloire that he became acquainted with two well-known Jansenists with whom he became fast friends, Jacques Jubé, the future liturgist, and Jean-Baptiste-Paulin d’Aguesseau, the brother of the chancellor of France, Henri-François d’Aguesseau. Through his father, who on occasion retired to his country home near the famous place of pilgrimage of Mont Valérien, Varlet had already come into contact with the Congrégation des prêtres du Calvaire, with the result that in 1699 he had asked to be admitted and had been accepted as a member of this community. All these circles, which were strongly impregnated with Jansenism, were going to contribute in no small way to determining his future orientation.

In 1706 he was ordained a priest and was immediately assigned to parishes in the Paris suburbs. In 1708 he was parish priest at Conflans-Sainte-Honorine. Three years later, faced with all sorts of difficulties, he went to see the directors of the Séminaire des Missions Étrangères in Paris and asked to be admitted into their society in order to devote himself to the evangelization of pagans, as he had long desired. In 1712 he resigned as parish priest and came to put himself at the disposal of his new superiors. He was then designated to go to restore the mission to the Tamaroas (Cahokia, now East St Louis, Ill.), which had remained practically without a priest since Marc Bergier*’s death in 1707.

Varlet sailed from Port-Louis (dept. of Morbihan) at the end of January 1713 and on 6 June he arrived at Mobile (Mobile Bay, Ala.). Upon his arrival he suffered an attack of dysentery which almost carried him off, and he had to resign himself to staying where he was with his fellow religious, Albert Davion* and François Le Maire, while waiting until more favourable circumstances allowed him to push on to the Illinois country.

His first impressions were on the whole negative. Louisiana, he wrote, was not, as was believed in France, “one of the marvels of the world.” Undoubtedly the soil seemed fertile, the forest abounding in game, but for the moment what one beheld was only a “wild, uncultivated” country, which was consequently not very attractive. As for the work of evangelization, the picture that he painted was scarcely more cheering. The missionaries were too few in number, and the difficulties they encountered in their apostolate among amazingly primitive and rough tribes too great.

Varlet resolved to take advantage of an expedition organized at the beginning of 1715 by Lamothe Cadillac [Laumet*], governor of Louisiana – at that time exploration was going on for mines in the upper Mississippi country – to go to Cahokia to establish himself at the Sainte-Famille mission, as the seminary of Paris had asked him to do. That same year he was appointed vicar general to the bishop of Quebec for the Mississippi and Illinois region. He was to remain a little more than two years at Cahokia, devoting the greater part of his time to his Tamaroas, not hesitating to accompany them to their hunting grounds when winter arrived, but encountering the same obstacles as had his predecessor Bergier. In the spring of 1717 he thought of leaving for Quebec. His idea was to go there to recruit a certain number of assistants, but particularly to consolidate his position in the face of claims put forward by the Jesuits, who continued to deplore the presence of priests of the seminary of Quebec in a region that they considered had been reserved for them.

Varlet left Cahokia on 24 March and succeeded in reaching Quebec on 11 September. On 6 October he received from Bishop Saint-Vallier [La Croix*] confirmation of the privileges granted in 1698 for the Tamaroa mission. Taking advantage of the long winter months, he was successful besides in persuading the seminary to give him reinforcements. On 10 May 1718 Goulven Calvarin*, Dominique-Antoine-René Thaumur* de La Source, and Jean-Paul Mercier left for Cahokia. But Varlet himself was never to see the Illinois country again. He was recalled to Paris by his superiors and left Quebec around the beginning of October 1718; he had spent a little more than 13 months in the capital.

On 13 November he was at La Rochelle and a fortnight later in Paris, where he learned of his appointment as coadjutor to the bishop of Babylon, Louis-Marie Pidou de Saint-Olon. On 19 Feb. 1719, in Paris, he was consecrated titular bishop of Ascalon. One of the consecrating prelates was Louis-François Duplessis de Mornay, coadjutor to the bishop of Quebec. On the same day Varlet received letters from the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith informing him of Bishop Saint-Olon’s death and urging him to leave as soon as possible for his bishopric. In his haste he neglected, consciously or not, to call upon the papal nuncio, between whose hands he was supposed, as prescribed by Rome, to pronounce the oath of allegiance to the bull Unigenitus Dei Filius, which had been proclaimed on 8 Sept. 1713 and which condemned as heretical the 101 Jansenist propositions drawn from the Réflexions morales sur le Nouveau Testament (1699 edition) of the Oratorian Pasquier Quesnel. This “oversight” was fatal for him. Upon his arrival in Persia at the beginning of November 1719 he found himself interdicted by a decree of the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith from all exercise of his religious function. Obliged to retrace his steps, he went to take up his abode in Holland, where he had stayed some months earlier, on his way to his bishopric, and where he counted on being able to work for his justification. It did not take long for circumstances to lead him to identify his cause with that of the Dutch Jansenists. Not content with supporting them in their conflict with Rome, in 1724 he agreed to confer the office of bishop upon Cornelius Steenoven, who had been elected archbishop of Utrecht by the chapter of that city; he thus consecrated the rupture of these Jansenists with the Holy See, at the same time earning the title of “spiritual father” of the so-called Church of Utrecht. In 1723 he became an appellant against the bull Unigenitus and remained so until his death, despite the efforts made by François de Montigny, procurator of the Société des Missions Étrangères in Rome, to regularize his situation.

A missionary to the depths of his soul, he remained obsessed all his life by the problem of the salvation of unbelievers. His experience with the Tamaroas had left its mark on him. In 1733, at the height of his quarrels with Rome, he had written: “I still frequently miss the woods of America.” Perhaps he secretly wished that he had never left them.

D.-M. Varlet, Apologie de Mgr. l’évêque de Babilone . . . (Amsterdam, 1724); Lettre de Mgr. l’évêque de Babylone à Mgr. l’évêque de Montpellier pour servir de réponse à l’ordonnance de M. l’archevêque de Paris . . . (Utrecht, 1736); Lettre de Mgr. l’évêque de Babylone à Mgr. l’évêque de Senez, au sujet de la lettre de ce prélat sur les erreurs avancées dans quelques nouveaux écrits (n.p., 1737); Lettre de Monsieur l’évesque de Babylone, aux missionnaires du Tonquin (Utrecht, 1734); Réponse de Mgr. l’évêque de Babylone à Mgr. l’évesque de Senez . . . (n.p., 1736); Seconde apologie de Monseigneur l’évêque de Babilone . . . (Amsterdam, 1727). C. J. [Steenoven] et D.-M. [Varlet], Lettre de Mgr. l’archevesque d’Utrecht et de Mgr. l’évesque de Babylone à Mgr. l’évesque de Senez, au sujet du jugement rendu à Ambrun contre ce prélat (n.p., 1728).

AN, LL, 1591. Archives du Vatican, Fonds de la Secrétairerie d’État, Nonciature de France, 234, 389. Archives royales d’Utrecht (Pays-Bas), Fonds Port-Royal d’Ammersfoort, 3797. BN, mss, Fr. 22832; mss, NAF, 5398. Mandements des évêques de Québec (Têtu et Gagnon), I, 495–96. Nouvelles Ecclésiastiques; ou Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire de la Constitution Unigenitus (Paris), 1731, 195; 1735, 15; 1736, 81; 1737, 13; 1742, 105–8, 185–88. Auguste Jal, Dictionnaire critique de biographie et d’histoire (Paris, 1867), 726–29. Delanglez, French Jesuits in Louisiana, 71–74. Giraud, Histoire de la Louisiane française, I, 311. Edmond Préclin, Les Jansénistes du XVIIIe siècle et la Constitution civile du clergé; le développement du richérisme; sa propagation dans le bas clergé 1713–1791 (Paris, 1929). Pierre Hurtubise, “Dominique-Marie Varlet, missionnaire en Nouvelle-France,” SCHÉC Rapport, 1968, 21–32. B. A. van Cleef, “Dominicus Maria Varlet (1678–1742),” Internationale Kirchliche Zeitschrift (Berne), LIII (1963), 78–104, 149–77, 193–225.

[The reader may also consult Gosselin, L’Église du Canada jusqu’à la conquête, I, 331–35, and Anselme Rhéaume, “Mgr Dominique-Marie Varlet,” BRH, III (1897), 18–22, as well as Maximin Deloche’s article, “Un missionnaire français en Amérique au XVIIIe siècle: contribution à l’histoire de l’établissement des Français en Louisiane,” France, Comité des Travaux historiques, Bulletin de la section de géographie (Paris), XLV (1930), 39–60, which corrects several of their statements. p.h.]

Cite This Article

Pierre Hurtubise, “VARLET, DOMINIQUE-MARIE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/varlet_dominique_marie_3E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/varlet_dominique_marie_3E.html |

| Author of Article: | Pierre Hurtubise |

| Title of Article: | VARLET, DOMINIQUE-MARIE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1974 |

| Access Date: | April 28, 2025 |