Source: Link

STEWART, JOHN, schoolteacher, physician, surgeon, university educator, author, and military officer; b. 3 July 1848 in Black River, Richmond County, N.S., eldest son of the Reverend Murdoch Stewart, a Free Church minister, and Catherine McGregor; brother of Donald Alexander* and Thomas* Stewart; d. unmarried 26 Dec. 1933 in Halifax.

John Stewart’s father, a missionary who had come to Cape Breton Island as a member of the Church of Scotland, had joined the Free Church following the Great Disruption of 1843 [see George Brown*]. The boy was probably named for John Stewart*, an earlier missionary to Cape Breton who had also seceded to the Free Church. According to Scottish Highland tradition, he, as the eldest son, should have been dedicated to the ministry of the Gospel, but despite being a devout Christian, he took a different direction; the mantle fell instead on his brother Thomas. John’s first choice of profession was teaching, and after graduating from Truro’s Normal School about 1865, he spent some time in Black River and Sydney. But schoolmastering did not appeal to him. In 1868 he went to Scotland, where he worked the farm of a maternal aunt and may have attended humanities classes at the University of Edinburgh while he pondered his future career.

After returning to Nova Scotia in 1872, Stewart studied for a year in Dalhousie University’s faculty of medicine. He then continued his training at Edinburgh, the centre of medical education in the English-speaking world, and graduated in 1877. There he had been a pupil of Joseph Lister, the pioneer of antiseptic surgery. He so impressed his mentor that Lister invited the young man to accompany him as clinical clerk (senior assistant) when he went to London that year to become professor of clinical surgery at King’s College and its associated hospital. In 1878, however, although he had succeeded to the post of house surgeon, Stewart suddenly resigned in order to return to Nova Scotia. Lister did not want to lose his protégé and would not forget him. In August 1897, when the British Medical Association met in Montreal, he publicly praised Stewart. He would also present his former pupil with a copy of his two-volume Collected papers (Oxford, Eng., 1909).

Stewart’s reasons for leaving London were entirely personal rather than professional. His brother, James McGregor, a promising young lawyer, had been banished from Halifax by his family when he and his fiancée had a child out of wedlock. James took up residence in Pictou, a remote shire-town with which neither he nor his family had hitherto had any connection. After what appears to have been an agonizing struggle, in which his mother urged him to come back while his father counselled him to remain in London, John sacrificed his own career in order to support his brother. Blood was indeed thicker than water, even an ocean of it.

He buried himself in Pictou, where he would practise medicine for 16 years. The only general facility, the Provincial and City Hospital in Halifax, was more than 100 miles away. Operations had to be carried out at home, but Stewart was able to apply antiseptic procedures and the speed and dexterity he had learned in Edinburgh with great success. (He was not apparently the first in Nova Scotia to adopt Lister’s approach: in 1869 Alexander Peter Reid* told the Clinical Society of Halifax that he had used carbolic-acid spray in surgery for about a year.) In his leisure hours Stewart played football and lacrosse, took long walks with friends, and indulged his interest in botany and ornithology.

His reputation, which had preceded him, meant that he could not avoid public notice. In 1885 he was drawn into a cause célèbre involving the Provincial and City Hospital. Members of the institution’s medical board had resigned en masse in disagreement over the appointment of a house surgeon chosen by Nova Scotia’s Board of Public Charities. Stewart was evidently brought in as an expert adviser by Adam Carr Bell, Conservative mha for Pictou County, leader of the opposition, and chair of the House of Assembly’s standing committee on humane institutions, which investigated the imbroglio. In the end, the hospital was placed under the direct control of the provincial cabinet, and in 1887 it was renamed the Victoria General Hospital. Stewart continued to be interested in public hospitals. He had supported the Roman Catholic Sisters of Charity when they established the Halifax Infirmary in 1886, and he was instrumental in founding the first general hospital in the town of Pictou in 1893.

The following spring Stewart left for a six-month furlough in Britain. In June he dined with Lister in London. It was common knowledge that on his return Stewart would settle in Halifax, where he had been named examiner in surgery in Dalhousie University’s faculty of medicine, reconstituted seven years earlier. By this time he appears to have been well off, possibly as a result of careful investments. He moved his widowed mother and four unmarried sisters from Pictou to the metropolis to reside with him and set up as a consulting surgeon in a grand brick house in fashionable south-end Halifax designed for him by the elite architect James Charles Philip Dumaresq*. In 1898 Stewart was approached by Liberal mha Dr Arthur Samuel Kendall* with an invitation from Premier George Henry Murray* to become medical superintendent of the Victoria General Hospital, which had been suffering from financial mismanagement. He declined, though he had served on the provincial commission established two years earlier to look into the institution’s operations. His refusal led to the appointment of the first lay superintendent, William Wallace Kenney.

Stewart’s principled opposition to recognizing instruction given by the discredited Halifax Medical College (HMC) [see Edward Farrell*], which had come into existence when Dalhousie’s first faculty of medicine closed in 1875, as adequately qualifying students for degrees in medicine given by the university prompted him to resign from the faculty in 1904. He particularly deplored the limited academic training the college provided. Nothing could better illustrate the strength of his convictions when it came to professional matters. As university historian P. B. Waite points out, “The best surgeon in Halifax, Dr John Stewart,… resolutely refused to have anything to do with the Halifax Medical College.” Indeed, he had accepted appointment to Dalhousie in 1894 only because the university’s affiliation with the HMC had ended, at least officially, in 1889.

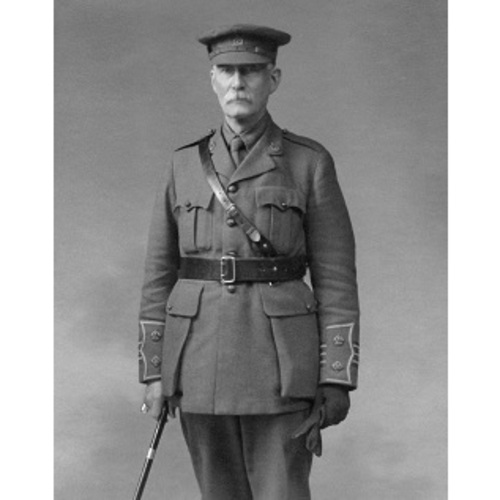

The HMC eventually disappeared, and in 1913 Stewart rejoined Dalhousie, this time as professor of surgery. Following the outbreak of World War I, the university in 1915 raised the No.7 Canadian Stationary Hospital, largely composed of Dalhousie medical and dental teaching staff, together with senior students and nurses. Stewart, who had enlisted that year, was everyone’s choice to command the unit; he did so with the rank of lieutenant-colonel. In France he personally attended German prisoners of war, a task made easier by his fluency in their language, which he had acquired while travelling in Germany and Switzerland in 1891. Two of his nephews were also involved in the war: John Murdoch Stewart, a doctor, worked under him; Donald McGregor Stewart would be killed in battle in September 1918. No.7 Stationary Hospital was inspected by George V on 3 July 1917, and Stewart afterwards proudly recalled how he had with difficulty refrained from informing the king that it was his 69th birthday. Declared medically unfit for further active service early in 1918, he was reassigned to the Canadian Army Medical Corps headquarters in London as consulting surgeon. He had been mentioned in dispatches, and in 1919 he was made a commander of the Order of the British Empire for his wartime contributions.

After returning to Canada that year, Stewart became dean of Dalhousie’s faculty of medicine; he continued in that capacity until 1932, when increasing deafness obliged him to retire. He served as president of the Dominion Medical Council in 1925 and had headed the Canadian Medical Association as early as 1905. Since the mid 1890s he had also contributed articles to medical journals. The golden jubilee in October 1927 of Stewart’s graduation from university was widely celebrated, but it was the centenary of Lister’s birth that year which brought him an honorary fellowship in the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. His alma mater had already, in 1913, conferred an lld on him, in recognition of his association with Lister, who had died the previous year.

The last decade of Stewart’s life was overshadowed by the disruption in the Presbyterian Church in Canada that resulted from efforts to form the United Church of Canada [see Mary Ellen Braden; Clarence Dunlop Mackinnon]. A strict evangelical Protestant and proponent of muscular Christianity, he had been an elder and the clerk of session at Pictou’s Knox Church in 1888. He was appalled by the church-union movement, which he saw as unpresbyterian, if not unchristian, and driven by secular motives. Throwing himself into the contest, he became the heart and soul of the resistance to union in Nova Scotia and served as honorary president of the Maritime branch of the Presbyterian Church Association in 1921. He was one of the charter members and original elders of the continuing Presbyterian congregation in Halifax, born of the disruption; a plaque in the Presbyterian Church of Saint David commemorates him.

His years with Lister, first as student and then as junior colleague, were the defining epoch of Stewart’s personal and professional life. Of the four young men who accompanied “the chief” to London in 1877 – the others were William Watson Cheyne, William Henry Dobie, and James Altham – Stewart was the disciple to whom Lister seems to have been closest personally. Their outlook on life was similar: Stewart was a puritanical Calvinist who disapproved of tobacco and alcohol and Lister a deep pessimist who had been raised a Quaker. Much of Stewart’s lecturing, teaching, writing, and, indeed, surgical practice was a prolonged apologia for Lister and Listerism. Where the master was concerned, Stewart succumbed to hero worship and hagiography. He never forgot, nor did he let anyone else forget, that he had been present at what he considered the birth of modern scientific medicine. After Lister died in 1912, Stewart wrote the memorial article for the Edinburgh Medical Journal, he presented the Canadian Medical Association’s first Listerian Oration in 1924, and he also gave one of the addresses at the centenary celebrations in Edinburgh three years later.

Not everyone regarded Lister so unequivocally, and Stewart lived to see his mentor’s methods considered old-fashioned. In surgery antisepsis was eventually superseded by asepsis. Lister was a man of his time, and Stewart, with filial devotion, remained a man of that time rather than his own, though an entire generation separated them. His continuing promotion of Lister’s ideas was perhaps in part an overcompensation for lost opportunities and a making of amends for having deserted his teacher in 1878, against his own better judgement and for a reason that looked much less compelling in retrospect: his brother, who was able to build a successful law practice before his premature death in 1897, could well have managed without him.

John Stewart’s achievements as an operating, consulting, and teaching surgeon are still to be fully assessed. In Canadian terms at least he was to surgery what Sir William Osler*, born a year later, was to general medicine in the Anglo-American world. Though he was not in the same league as a humanist and intellectual, Stewart merits historian Charles G. Roland’s summing-up of Osler: he “remains influential because he was a great clinician,… and because he had an enduring impact on colleagues and students.”

John Stewart’s portrait, commissioned by Dalhousie University’s faculty of medicine and painted by John William MacGillivray in 1931, hangs in the foyer of the Sir Charles Tupper Medical Building at the university. The whereabouts of another portrait, presented to Stewart by veterans of No.7 Canadian Stationary Hospital, is unknown.

Stewart is the author of “The address in surgery …,” Montreal Medical Journal, 25 (1896): 182–90; “The contribution of pathology to surgery,” Montreal Medical Journal, 31 (1902): 700–9; “Medical inspection of schools: report to the Canadian Medical Association,” Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal (Toronto), 1 (1911): 425–39; “A generation of surgery,” Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal, 1: 790–95; “Lord Lister,” Edinburgh Medical Journal, new ser., 8 (1912): 254–57; “Lord Lister,” Canadian Journal of Medicine and Surgery (Toronto), 31 (1912): 323–30; “Chloroform anaesthesia,” Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal, 4 (1914): 1053–64; “An appreciation of Sir John Rickman Godlee’s life of Lord Lister,” Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal, 8 (1918): 753–57; “First Listerian oration,” Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal (Montreal), October 1924, special no.: 1007–40; “The centenary of Lister,” Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal, 16 (1926): 1115–16; “Reminiscences of ‘the Chief,’” in Joseph, Baron Lister: centenary volume, 1827–1927, ed. A. L. Turner (Edinburgh and London, 1927), 141–46; “The general practitioner,” Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal, 18 (1928): 91; and “Lorenz Heister: surgeon (1683–1758),” Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal, 20 (1929): 418–19. His “Presidential address” to the Canadian Medical Assoc. in 1905 was published in the Maritime Medical News (Halifax), 17 (1905): 343–56. No comprehensive bibliography of his extensive writings exists.

Stewart’s personal papers, which would have included 30 years of correspondence with Lord Lister, were probably destroyed after the death of his last surviving sister in 1946. Only fragments remain, some in private hands. His wartime activities are well documented in his service record and the records of No.7 Canadian Stationary Hospital Havre at LAC (RG 150, Acc. 1992–93/166, box 9316-2 and R611-450-9). Stewart is mentioned in all the more substantial scholarly biographies of Lord Lister; see, for example, R. B. Fisher, Joseph Lister, 1827–1912 (London, 1977), which quotes letters from Stewart to his mother. His correspondence with David Alexander Stewart, a family friend, is in the David Alexander Stewart fonds at the AM (MG9, A54). The author gratefully acknowledges the advice and assistance of Dr T. J. (Jock) Murray, who is writing the official history of Dalhousie University’s faculty of medicine, of which he is dean emeritus.

DUA, MS-13-39 (John Stewart fonds). Halifax County Court of Probate (Halifax), Estate papers, no.13380. NSA, MG 1, vol.3196G/F1-8 (John Stewart fonds). Acadian Recorder (Halifax), 1894–1930. Colonial Standard (Pictou, N.S.), 1878–95. Halifax Herald, 1894–1933. Barry Cahill, The thousandth man: a biography of James McGregor Stewart (Toronto, 2000). D. A. Campbell, “Medical education in Nova Scotia,” Maritime Medical News, 22 (1910): 201–17. J. T. H. Connor, “Joseph Lister’s system of wound management and the Canadian medical practitioner, 1867–1900” (ma thesis, Univ. of Western Ont., London, Ont., 1980); “‘To be rendered unconscious of torture’: anaesthesia in Canada, 1847–1920” (m.phil. thesis, Univ. of Western Ont., 1983). C. D. Howell, A century of care: a history of the Victoria General Hospital in Halifax, 1887–1987 (Halifax, 1988); “Elite doctors and the development of scientific medicine: the Halifax medical establishment and 19th century medical professionalism,” in Health, disease and medicine: essays in Canadian history, ed. C. G. Roland ([Toronto], 1984), 105–22; “Medical professionalization and the social transformation of the Maritimes, 1850–1950,” Journal of Canadian Studies (Peterborough, Ont.), 27 (1992–93), no.1: 5–20; “Reform and the monopolistic impulse: the professionalization of medicine in the Maritimes,” Acadiensis, 11 (1981–82), no.1: 3–22; “Scottish influences in nineteenth-century Nova Scotian medicine: a study of professional, class and ethnic identity,” in Myth, migration and the making of memory: Scotia and Nova Scotia, c. 1700–1990, ed. Marjorie Harper and M. E. Vance (Winnipeg, 1999), 202–17. D. L. MacIntosh, “Dr. John Stewart,” Dalhousie Medical Journal (Halifax), 2 (1937), no.3: 6–11. N.S., House of Assembly, Journal and proc., 1897, app.15 (Victoria General Hospital, report of the commissioners appointed to enquire into management). S. M. Penney, “‘Marked for slaughter’: the Halifax Medical College and the wrong kind of reform, 1868–1910,” Acadiensis, 19 (1989–90), no.1: 27–51. H. L. Scammell, “History of Canadian surgery: John Stewart,” Canadian Journal of Surgery (Toronto), 4 (1960–61): 263–67. P. C. Wagg, A living community: a history of St. George’s Channel (West Bay, N.S., 2005). P. B. Waite, The lives of Dalhousie University (2v., Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1994–98), 1.

Cite This Article

Barry Cahill, “STEWART, JOHN (1848-1933),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/stewart_john_1848_1933_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/stewart_john_1848_1933_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Barry Cahill |

| Title of Article: | STEWART, JOHN (1848-1933) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2017 |

| Access Date: | April 28, 2025 |