Source: Link

RIVERIN, DENIS, secretary of Intendant Duchesneau*, representative of the farmers of the Compagnie de la Ferme du Roi, member of the Conseil Souverain, one of the directors of the Compagnie du Nord, and of the Compagnie de la Colonie, lieutenant general of the provost court of Quebec, fur-trader, landowner, and commercial fisherman; b. at Tours, c. 1650, the son of Pierre Riverin, a merchant and bourgeois, and of Madeleine Mahyet; d. February 1717.

Riverin came to New France in 1675 as secretary to the new intendant, Duchesneau. Like many of the bourgeois-gentilshommes, members of the élite in New France, he fulfilled numerous functions of the colony. He was a member of the civil administration, and engaged in a wide variety of commercial activities: the fur and fishing trades, exporting and importing.

During his early career, from roughly 1675 to the early 1680s he was Duchesneau’s secretary, and at the same time he represented Jean Oudiette, the holder of the monopoly of the Compagnie de la Ferme du Roi in New France. In 1694 he became a titular member of the Conseil Souverain, and a full-fledged member in 1698. He retained the latter post until 1710, in spite of the fact that he had returned to France in 1702 and never came back to the colony. In 1710, moreover, he was named lieutenant general of the provost court of Quebec. Although he never personally carried out the duties of this appointment he drew the salary provided. These last two appointments show the kind of favouritism which Riverin enjoyed, thanks no doubt to the protection of the governors and intendants who thought well of him, at least until the arrival of Rigaud de Vaudreuil and Jacques Raudot. A further factor which helps to explain Riverin’s position in the society of his time was the patronage of Tantouin de La Touche, a member of the ministry of Marine who had served in New France till 1701. Riverin also appears to have been well thought of by the minister of Marine, Louis Phélypeaux de Pontchartrain.

Until the departure of Duchesneau in 1682, Riverin appears to have engaged in the fur trade as Oudiette’s representative as well as on his own account, if we are to believe his critics, Le Febvre* de La Barre and Ruette d’Auteuil. There is no doubt that he was, as W. J. Eccles had pointed out, “the Intendant’s very able secretary,” quite evidently under Duchesneau’s protection. When the Compagnie de la Colonie was formed in 1700, Riverin became one of its first directors. He was named the representative of the company in France in 1702; his position was renewed in 1706 and he held this post until his death in 1717, although other directors of the company claimed that he was displaced in 1713.

To be appointed to the post of director of a company during this period, a person had to own a certain number of shares, and moreover had to be elected by the other shareholders of the company who had the right to a deliberative voice. As agent of the company in France Riverin was responsible for the metropolitan administration of the company’s affairs. He was the agent who found and leased warehouse space, who placed orders for trade goods and supplies, and, perhaps most important, who arranged for the credit and the loans necessary to carry out the company’s business.

His views on the fur trade were somewhat contradicted by those he later put forward on the fishing trade. When he was involved in the fur trade in New France, he championed the need for fur-trading licences (congés), and did not object to the flow of men from the colony to the pays d’en haut. As a commercial fisherman, however, he insisted that young men should be kept in the colony, albeit by colony he understood the eastern extremities.

About 1688 he extended his commercial interests to include the fishing trade. Between 1688 and 1702, we find Riverin, in association with François Hazeur, Augustin Le Gardeur de Courtemanche, and several others, acquiring land concessions. On 19 Jan. 1689, he was granted the seigneury of Belle-Isle; in 1696, he leased three seigneuries for seven years; he paid 1,500 livres for a bark in 1701 and in the same year, in partnership with François Hazeur, leased the fur and fishing trade of Tadoussac for 12,700 livres per year. The significance of this sum can be appreciated by comparing it with a high average annual wage for an artisan of 600 livres per year.

Riverin wrote several interesting memoirs on the fishing trade which reveal the complexity of commercial organization in New France, and reflect what could be called an ideology of commercial imperialism. Riverin showed that the establishment of a successful commercial endeavour in the colony required the co-operation of metropolitan financiers – in this case the merchants of La Rochelle. Riverin justified the permanent extension of the frontiers of the colony, and thus its defence perimeter, by pointing out its military and economic implications. He claimed that the fishing trade could employ 500 men, but would require protection. He therefore requested assistance from the French state for his fishing stations. One thing led to another, for the logic of the situation required free shipping rights for his supplies. In 1696, he requested free transport for 20 casks. Riverin never explained, however, the possible contradiction between eastern and western expansion, which would draw men to the frontiers, and the maintenance of an adequate defence system in the heart of the colony.

The period after 1702 may be said to be different in content and in context for Riverin. Prior to this date he was personally engaged in the commercial activities and the political life of the colony. After this time his position was a little parasitical, and appears to have depended as much on influence as it did on accomplishment. When he was named deputy of the Compagnie de la Colonie in France, his salary was set at 6,000 livres per year. His services must have been satisfactory, for he was reappointed in 1706 but at a salary of 3,000 livres per year. The heyday of the company was at an end; it was in effect bankrupt. The various disputes over Riverin’s character and contributions date mainly from this year. He insisted that he had a right to a full salary from 1702 to 1716, but his partners in New France rejected his claims. Mathieu-Francois Martin de Lino, who had once occupied the post then held by Riverin, suggested that the colony’s interests would be better served if they were represented by one better informed and less concerned with personal gain. Ruette d’Auteuil, sometimes as unreliable a witness as Riverin, accused the latter of conniving with Aubert, Neret, and Gayot, the group that took over the monopoly of the Compagnie de la Ferme du Roi from the Compagnie de la Colonie. The acrimonious disputes over Riverin’s salary can be only partially explained by the amount of money involved, although he is said to have received the not inconsiderable sum of 69,000 livres between 1702 and 1716. At the heart of the matter was the dislocation of favoured groups which took place when the upper administrators of the colony were changed. The vicissitudes of favouritism are apparent in the writings of the governors and intendants of the colony. Buade* de Frontenac and Duchesneau favoured Riverin. Their successors, de Meulles and La Barre, described Riverin as one, possessing “an extraordinary spirit of gain . . . ,” and accused him of trying to monopolize the fishing industry. On the other hand, Brisay de Denonville and Bochart de Champigny respectively depicted Riverin as “poor Riverin” and as a very well liked, honest man. Later administrators such as Vaudreuil and Raudot were extremely critical of Riverin’s activities in France. It should be added that Riverin, somewhat tactlessly, although accurately, said that Vaudreuil was tied to his wife’s apron strings. What is perhaps most important is that as long as Riverin had the support of influential men in the French administration he managed to retain his post and its remuneration. The year 1715 was a key date in the rise and fall of Denis Riverin; that year the king died, the council of Marine was established, and administrators and merchants in New France took their revenge. Perhaps fortunately, Riverin died, thus escaping a further reduction of his influence and income.

A just assessment of Riverin requires an appreciation of the milieu in which he lived. He was certainly able. At the same time, he was very self-seeking. When his personal interests and those of the colony coincided, his contributions were considerable; when they did not, his tendency towards acrimony made his views suspect.

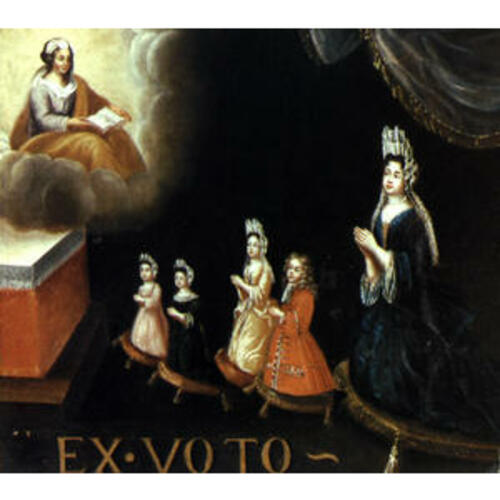

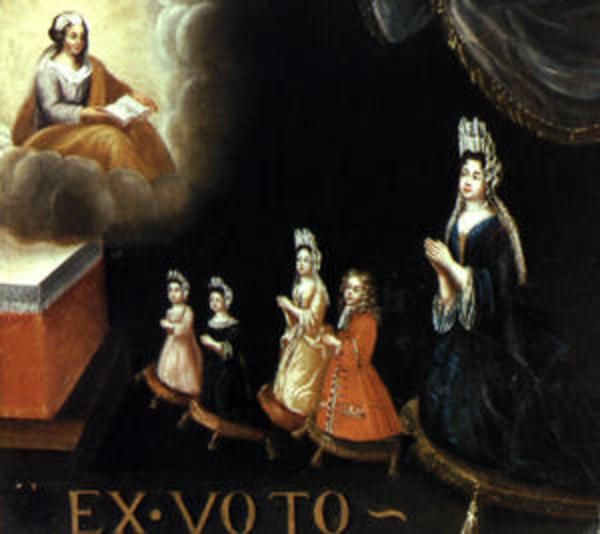

In 1696, Riverin had married Angélique Gaultier, the daughter of Philippe Gaultier*, Sieur de Comporté, and of Marie Bazire. The bride’s guardian was François Hazeur, an occasional business partner of Riverin. In the marriage contract, Riverin is described as a director of the “Compagnie des Pesches Sédentaires de Canada.” Riverin and his wife had four children born between 1697 and 1700.

There are various opinions regarding the date of his death. Ignotus [Thomas Chapais] wrote that it occurred in 1718. Riverin’s last extant writing is dated July 1716. P.-G. Roy claimed that he died in 1717. In a document dated 5 May 1717, the council of Marine referred to him as the late Denis Riverin. Shortt’s date of February 1717 thus appears possible.

AJQ, Greffe de Louis Chambalon; Greffe de François Genaple. AN, M, Lettre de Riverin sur les affaires du Canada, 21 mars 1704; Col., C11G, 1–6. AQ, Coll. P.-G. Roy, Dossier Denis Riverin; NF, Coll. pièces jud. et not., 305, 3267. “Correspondance de Frontenac (1672–82),” APQ Rapport, 1926–27. Documents relating to Canadian currency during the French period (Shortt). “Lettres et mémoires de F.-M.-F. Ruette d’Auteuil.” P.-G. Roy, Inv. concessions, III, IV, V. Gareau, “La prévôté de Québec,” 51–146. Eccles, Canada under Louis XIV. Fauteux, Essai sur l’industrie sous le régime français. Cameron Nish, Les bourgeois-gentilshommes de la Nouvelle-France 1729–1748 (Montréal, 1968). J.-E. Roy, “Les conseillers au Conseil souverain de la Nouvelle-France,” BRH, I (1895), 171. P.-G. Roy, “Notes sur Denis Riverin,” BRH, XXXIV (1928), 65–76, 128–39, 193–206.

Cite This Article

Cameron Nish, “RIVERIN, DENIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/riverin_denis_2E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/riverin_denis_2E.html |

| Author of Article: | Cameron Nish |

| Title of Article: | RIVERIN, DENIS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1969 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |