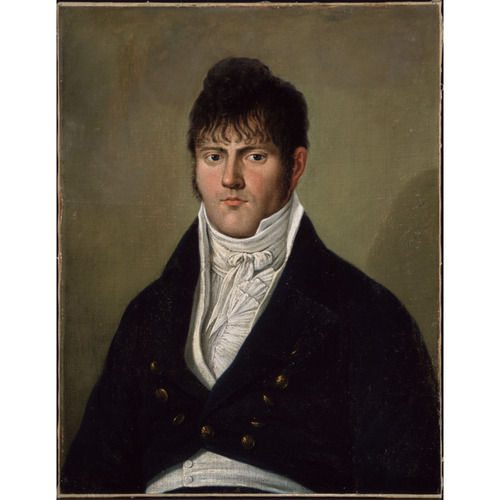

RASTEL DE ROCHEBLAVE, PIERRE DE, fur trader, businessman, militia officer, jp, politician, and office holder; b. 9 March 1773 in Kaskaskia (Ill.), son of Philippe-François de Rastel de Rocheblave and Marie-Michelle Dufresne; m. 9 Feb. 1819 Anne-Elmire Bouthillier in Montreal, and they had nine children; d. 5 Oct. 1840 in Coteau-Saint-Louis on Montreal Island.

Philippe-François de Rastel de Rocheblave, sometimes called the Chevalier de Rocheblave, came to New France during the Seven Years’ War and seems to have fought in the Ohio region. He was at Fort Chartres (near Prairie du Rocher, Ill.) in 1760, and in the following years he established himself at Kaskaskia as an officer in the colonial regular troops. Around 1765 he moved from Kaskaskia, which had passed into British hands, to Ste Genevieve (Mo.) on the west bank of the Mississippi in territory that France had ceded to Spain. There he took command of the Illinois country for the Spaniards. After quarrelling with the Spanish governor in New Orleans, he recrossed the Mississippi around 1773 or 1774 and settled once more at Kaskaskia, where he soon became the commandant, this time in the service of the British. In July 1778 he was taken prisoner by American troops under George Rogers Clark and sent to Virginia. Evidently having escaped, in the spring of 1780 he reached New York, which was still in British hands. Shortly after the war ended, he settled with his family in Montreal, and from 1789 they lived at Varennes. Rocheblave took an interest for a time in the fur business, and from 1792 until his death on 22 April 1802 he served as member for Surrey in the Lower Canadian House of Assembly. In May 1801 he was appointed clerk of the land roll.

Pierre de Rastel de Rocheblave himself also went into the fur trade. In 1786 he seems to have been looking after his father’s interests at Detroit. The Chevalier de Rocheblave bought goods in Montreal and sent them to Detroit, and was doing business with Étienne-Charles Campion*, Richard Dobie*, James Fraser, and Jean-Baptiste Barthe, John Askin*’s brother-in-law and agent, among others. Subsequently Pierre worked as a clerk in Detroit for “Messrs Grant, Alexr Mackenzie [Alexander McKenzie*], and Mcdonell [possibly John McDonald* of Garth].” From December 1797 to May 1798 he was in Montreal, where, probably using money he had saved in the preceding decade, he hired 12 voyageurs to go to Michilimackinac (Mackinac Island, Mich.) and the Mississippi region.

Rocheblave was a founder of the New North West Company, also called the XY Company [see John Ogilvy*]. Established on 20 Oct. 1798, the firm was intended to compete with the NWC, which dominated the fur trade in the northwest. One of the six wintering partners, he was put in charge of the Athabasca department. The fierce competition between the two rivals sometimes degenerated into acts of violence. In 1803 Rocheblave himself was indirectly involved in one of them. His clerk, Joseph-Maurice Lamothe*, killed James King, the clerk working for Nor’Wester John McDonald of Garth. McDonald, who recorded the event in his diary, did not hold it against Rocheblave, however, and even called him “a gentleman.”

When the XY Company merged with the NWC on 5 Nov. 1804, Rocheblave was the only Canadian other than Charles Chaboillez* to be made a proprietor in the reorganized NWC. He was put in charge of the Red River department, a post he held until 1807. At the annual meeting that year he was given responsibility for the Athabasca department, and then in the summer of 1810 for the Pic department on Lake Superior. The following winter he ordered his clerk to starve out independent trader Jean-Baptiste Perrault and his two engagés, who had established themselves on the Pic River. Perrault had to turn to Rocheblave for food in February 1811, and Rocheblave took advantage of his predicament to get his trade goods for a pittance.

An incident that occurred during the annual meeting of the NWC’s agents and winterers at Fort William (Thunder Bay, Ont.) in the summer of 1811 demonstrates the influence Rocheblave had acquired. On 28 January William McGillivray*, John Richardson*, and John Jacob Astor had reached an agreement in New York to set up the South West Fur Company. By its terms the shares of the new firm were to be divided among Astor himself and the two Montreal firms of McTavish, McGillivrays and Company and Forsyth, Richardson and Company. The NWC was to hand over its trading posts on American territory to the South West Fur Company. This arrangement required the approval of the members of the NWC and when McGillivray submitted the terms to the meeting in July, several winterers strongly objected to them. After much discussion McGillivray finally brought the dissenters round by proposing Rocheblave as manager of the new company.

War between the United States and Great Britain apparently kept the South West Fur Company’s plans in abeyance, however, and enabled the NWC to consolidate its hold on the fur trade in American territory. Rocheblave himself scarcely had time to assume his duties, for on 2 Oct. 1812 he became captain in the Corps of Canadian Voyageurs recruited from the NWC. After the unit was disbanded, he served on the staff of the sedentary militia of Lower Canada with the rank of major in the “Indian and conquered countries,” according to his commission, dated 1 Sept. 1814.

In the post-war years Rocheblave played an increasingly important role in the fur business. On 6 Feb. 1815 he entered into partnership with Forsyth, Richardson and Company, McTavish, McGillivrays and Company, and the NWC to form a commercial enterprise for an eight-year period. In this new and unnamed organization each of the three participating firms held nine shares and Rocheblave three. He was to receive an annual salary of £500. In return, the agreement stipulated: “He is to make the necessary preparations for the annual Outfits, to hire and engage the men, provide boats and canoes, provisions &c bale up and transport the Goods, and generally do everything that is termed Making the Outfits; He is to manage and settle the business of the Concern at Michilimakinac, or wherever else it may be found convenient to transact the affairs of the Concern, assort, and bale the Furs for shipping, and deliver each Fall in due season a correct Memorandum of goods for this trade for the ensuing year.”

Within months Forsyth, Richardson and Company, McTavish, McGillivrays and Company, and Rocheblave reached a new agreement with Astor to carry on the fur trade in American territory jointly for a five-year period. The agreement was, however, terminated before it expired. In April 1816 Congress passed an act restricting fur-trade licences on United States territory to citizens of that country, and Astor bought out the interests of his Canadian partners the following year. In the mean time on 24 April 1817 Rocheblave had succeeded Kenneth MacKenzie* as the NWC agent for Sir Alexander Mackenzie and Company. This new appointment brought him an annual salary of £400 and one per cent of the firm’s profits. Around the same time he was given joint responsibility for the voyageurs’ fund with Thomas Thain*.

Since he was in charge of organizing the western fur trade for the Canadian firms, Rocheblave was inevitably affected by the conflict surrounding the early days of the Red River settlement (Man.). When Lord Selkirk [Douglas*] seized Fort William in August 1816, he ousted Rocheblave and the other NWC partners there. Rocheblave assisted William McGillivray in the expedition that recaptured the fort in the spring of 1817. A year later he was called to testify at the trial of Colin Robertson and others accused of having destroyed the NWC’s Fort Gibraltar (Winnipeg) in the spring of 1816; all were acquitted.

Early in 1818 Rocheblave looked after transportation for two of the first Catholic priests in the west. In February, Bishop Joseph-Octave Plessis* had given Abbé Pierre-Antoine Tabeau* the task of making preparations for the westward journey of four missionaries, abbés Joseph-Norbert Provencher*, Sévère Dumoulin*, and Joseph Crevier, dit Bellerive, and seminarist William Edge. To preserve the missionaries’ independence Tabeau proposed that the NWC and the HBC each supply transportation for two of them. Lord Selkirk objected to hiring several of the men whom Tabeau suggested, but Rocheblave let him choose the voyageurs, and he personally took Tabeau as far as Fort William. He also provided the missionaries with letters of recommendation to the NWC posts and took it upon himself to forward their mail to Montreal, to the great satisfaction of the church authorities.

In July 1821, when Nicholas Garry* went to Fort William to settle the details of the NWC’s merger with the HBC, Rocheblave, who was present, was given the responsibility for drawing up the inventory of the NWC assets. He seems to have devoted some years to the task; in September 1822, for example, he went with John Stewart to Tadoussac, in Lower Canada, for this purpose.

Two months later, in Montreal, McGillivrays, Thain and Company was formed to liquidate the affairs of McTavish, McGillivrays and Company and to serve as agent for the HBC, looking after its interests in the Montreal district. But in August 1825 Thomas Thain, who was in charge of the firm’s business at Montreal, collapsed under the burden and returned to Great Britain. Simon McGillivray entrusted management of the HBC interests to Rocheblave in February 1826. He did not have this responsibility for long, however. In a letter to the company’s directors in London dated 14 June Governor George Simpson* noted: “De Rocheblave has acted very efficiently and properly during his interim management of the Company’s affairs here at Montreal. His duties are now finished.” Rocheblave did act as the HBC agent in Trois-Rivières in 1826 and 1827 before retiring permanently from the fur business, in which he had worked for nearly four decades.

Though he was in his mid fifties, Rocheblave did not have the temperament to remain idle. For a decade he had been channelling his money into the purchase of land, acquiring part of Coteau-Saint-Louis in particular. He had settled there in 1819 with his young wife on a property previously owned by Joseph Frobisher*. As the years went by, Rocheblave bought 12 or more pieces of land in the seigneuries of Châteauguay and La Salle, which he rented out along with other properties and shops in Montreal. Moreover he acquired 1,000 acres in Bristol Township on the Ottawa River. He became a partner in the Montreal firm of LaRocque, Bernard et Compagnie, which was in business from 1832 to 1838. With three other Canadians, his father-in-law Jean Bouthillier, François-Antoine La Rocque*, and Joseph Masson, he promoted the construction of the first railway in the Canadas, the Champlain and St Lawrence Railroad.

Despite his numerous activities Rocheblave went into politics. His father and brother had been assemblymen, and from 1824 till 1827 he himself held the seat for Montreal West. On 9 Jan. 1832 he was called to the Legislative Council, and when it was replaced by the Special Council in 1838, he became a member of that body, on which he remained until his death. Being of a rather conciliatory disposition, he always maintained a moderate attitude in political matters, during a troubled period when radical stances were common. In the assembly he had sometimes voted with the Patriote bloc, at other times with the government’s supporters, a pattern that did not, however, prevent Louis-Joseph Papineau* from showing confidence in him. Later, even though he was at times shocked by the behaviour of the governor, in particular that of Lord Aylmer [Whitworth-Aylmer], Rocheblave did not take a more radical position. In November 1837, along with 11 other Canadian magistrates, he signed an address to the inhabitants of the district of Montreal urging them to abstain from violence. The following January, as president of the Association Loyale Canadienne du District de Montréal, which was circulating a petition against the plan to unite Upper and Lower Canada, he signed a declaration stating the organization’s views. This conciliatory attitude unfortunately displeased certain Patriotes, including Louis-Victor Sicotte*, who in a letter to Ludger Duvernay* said Rocheblave was incompetent and called him a pygmy. Yet in December 1838 Rocheblave was among those testifying before a court martial in favour of Guillaume Lévesque*, a young Patriote who narrowly escaped being hanged.

Rocheblave took on various public responsibilities in addition to his business and political activities. He was churchwarden of the Montreal parish of Notre-Dame (1817), justice of the peace for the district of Montreal (1821), juror in the Court of Oyer and Terminer (1823), treasurer of the committee for building the new church of Notre-Dame (1824), commissioner for the exploration of the territory between the Rivière Saint-Maurice and the Ottawa (1829), member of the grand jury of the Court of King’s Bench and commissioner of roads (1829), commissioner for the relief of the insane and foundlings, for the supervision of the building of the Lachine Canal, and for building a new prison in the district of Montreal (1830), commissioner to draw the boundary between Lower and Upper Canada (1831), commissioner for rebuilding government property located in Montreal (1832), commissioner for the civil erection of parishes for several years (from 1832), and commissioner to erect a jail and court-house in Missisquoi County (1834). In 1836, after Montreal’s charter had expired, Rocheblave was appointed to the Court of Special Sessions of the Peace created to run municipal affairs. The following year he was made a commissioner to administer the oath of allegiance.

To maintain that Rocheblave reached the top of his economic and political world solely because of his social origins would be injudicious. Certainly, his father had been a governor in the colonial administration, but in a region of minor importance; the elder Rocheblave had also been a member of the House of Assembly, but at a time when the post did not necessarily confer a privileged rank; he tried his hand at the fur business just when Pierre was starting out, but he did not make a fortune in it, quite the reverse. Pierre de Rastel de Rocheblave seems to have owed his rise in society rather to his personality, which was marked by determination and a conciliatory way of dealing with people. Most statements by his contemporaries confirm this view. Only the eldest of Rocheblave’s children benefited from his success, the others having died young. In the fashionable circles of Montreal at the end of the 19th century his daughter Louise-Elmire had a salon that for many years drew distinguished visitors to enjoy “magnificent dinners that went on for hours.” She died unmarried on 9 Aug. 1914 in Montreal, and with her the Canadian branch of the Rastel de Rocheblaves disappeared.

[Pierre de Rastel de Rocheblave’s papers were lost when the house his widow occupied was destroyed by fire in 1860. That the materials illustrating Rocheblave’s activities are widely scattered and consequently difficult to piece together is no doubt part of the reason he does not occupy a place in Canadian historiography commensurate with his importance. p.d. and m.o.]

ANQ-M, CE1-51, 15 janv. 1820; 26 juin, 11 juill. 1821; 1er nov. 1822; 9 sept. 1824; 10 déc. 1826; 14 fév. 1830; 7 juin, 10 juill. 1832; 27 déc. 1834; 30 avril 1835; 3 janv. 1838; 8 oct. 1840; 22 mars 1844; 2 mai 1846; CN1-28, 7 déc. 1820; CN1-134, 2 mai 1816; 8–9 avril 1817; 17 mars 1819; 3, 7 oct., 29 déc. 1820; 9 févr., 3 mai 1821; 7 janv., 27 avril 1822; 5 août 1823; 30 oct. 1826; 12 juin 1827; 18 janv., 1er mars, 11 avril, 24, 31 mai, 16 juill. 1828; 24 févr., 1er oct. 1829; 23 oct: 1830; 12 janv., 13, 31 mai, 20 juill., 6 août 1831; 19 sept., 27 déc. 1832; 22 juill. 1833; 10 juin 1835; 23 nov. 1836; 12 oct., 10 nov. 1837; 25, 31 janv., 5 févr., 30 mai, 13 oct. 1838; 19 janv., 20 avril 1839; CN1-167, 23 juin, 28 sept. 1802; 24, 29 mars 1813; CN1-192, 1er août 1835, 29 avril 1836, 9 avril 1839; CN1-194, 6 févr. 1819, 9 nov. 1831; CN1-216, 6, 26 mars, 5 juill. 1838; CN1-224, 23 sept. 1836; 12 oct. 1840; 18 juin, 29 juill. 1841; 12 juill. 1842; 19 sept. 1844; 2 avril 1845; CN1-269, 12 juin 1813; CN1-320, 20 mai 1835; CN1-396, 3 févr. 1836, 30 nov. 1838. ANQ-Q, P-362/1. ASQ, Fonds Viger–Verreau, sér.O, 049, no.15; 0521. AUM, P 58. PAC, MG 8, G14; MG 19, B3; National Map Coll., H1/300, 1831. PAM, HBCA, D.4; E.20/1: f.212. T.-R.-V. Boucher de Boucherville, “Journal de M. Thomas Verchères de Boucherville . . . ,” Canadian Antiquarian and Numismatic Journal, 3rd ser., 3 (1901). Les bourgeois de la Compagnie du Nord-Ouest (Masson). Gabriel Franchère, Journal of a voyage on the north west coast of North America during the years 1811, 1812, 1813, and 1814, trans. W. T. Lamb, intro. W. K. Lamb (Toronto, 1969). D. W. Hannon, Sixteen years in the Indian country: the journal of Daniel Williams Harmon, 1800–1816, ed. W. K. Lamb (Toronto, 1957). HBRS, 2 (Rich and Fleming); 3 (Fleming). Robert La Roque de Roquebrune, Testament de mon enfance (2e éd., Montréal, 1958). L.C., House of Assembly, Journals, 1828–29, app.; 1830, app. Alexander Mackenzie, The journals and letters of Sir Alexander Mackenzie, ed. W. K. Lamb (Toronto, 1970). New light on the early history of the greater northwest: the manuscript journals of Alexander Henry . . . and of David Thompson . . . , ed. Elliott Coues (3v., New York, 1897; repr. 3v. in 2, Minneapolis, Minn., [1965]). “Papiers Duvernay,” Canadian Antiquarian and Numismatic Journal, 3rd ser., 6 (1909): 87–90. L.-J. Papineau, “Correspondance” (Ouellet), ANQ Rapport, 1953–55: 185–442. J.-B. Perrault, Jean-Baptiste Perrault, marchand voyageur parti de Montréal le 28e de mai 1783, L.-P. Cormier, édit. (Montréal, 1978). Thunder Bay district, 1821–1892: a collection of documents, ed. and intro. [M.] E. Arthur (Toronto, 1973). Wis., State Hist. Soc., Coll., 3 (1857); 18 (1908); 19 (1910). Montreal Gazette, 6 Oct. 1840. Quebec Gazette, 25 Oct. 1821, 12 Sept. 1822, 26 May 1823, 7 Oct. 1840. Quebec Mercury, 16 Dec. 1805. F.-J. Audet, Les députés de Montréal. Caron, “Inv. de la corr. de Mgr Panet,” ANQ Rapport, 1935–36: 157–272; “Inv. de la corr. de Mgr Plessis,” 1927–28: 215–316; 1928–29: 87–208; “Inv. de la corr. de Mgr Signay,” 1936–37: 123–330. Béatrice Chassé, “Répertoire de la collection Couillard–Després,” ANQ Rapport, 1972: 31–81. Louise Dechêne, “Inventaire des documents relatifs à l’histoire du Canada conservés dans les archives de la Compagnie de Saint-Sulpice à Paris,” ANQ Rapport, 1969: 147–288. Desjardins, Guide parl. Desrosiers, “Inv. de la corr. de Mgr Bourget,” ANQ Rapport, 1945–46: 135–224; “Inv. de la corr. de Mgr Lartigue,” 1942–43: 1–174; 1944–45: 175–266. The founder of our monetary system, John Law, Compagnie des Indes & the early economy of North America: a second bibliography, comp. L. M. Lande (Montreal, 1984). Philéas Gagnon, Essai de bibliographie canadienne . . . (2v., Québec et Montréal, 1895–1913; réimpr. Dubuque, Iowa, [1962]), 2. É.-Z. Massicotte, “Répertoire des engagements pour l’Ouest conservés dans les Archives judiciaires de Montréal . . . [1620–1821],” ANQ Rapport, 1942–43: 261–397; 1943–44: 335–444; 1944–45: 309–401. Officers of British forces in Canada (Irving). Quebec almanac, 1815–16. Monique Signori-Laforest, Inventaire analytique des Archives du diocèse de Saint-Jean, 1688–1900 (Québec, 1976). Turcotte, Le Conseil législatif. Norman Anick, The fur trade in eastern Canada until 1870 (Parks Canada, National Hist. Parks and Sites Branch, Manuscript report, no.207, Ottawa, 1976). Brown, Strangers in blood. Denison, Canada’s first bank. W. T. Easterbrook and H. G. J. Aitken, Canadian economic history (Toronto, 1967), 176–77. R. D. Elmes, “Some determinants of voting blocs in the assembly of Lower Canada, 1820–1837” (ma thesis, Carleton Univ., Ottawa, 1972). G. P. de T. Glazebrook, A history of transportation in Canada (Toronto, 1938; repr. in 2v., New York, 1969), 1: 43. Hochelaga depicta . . . , ed. Newton Bosworth (Montreal, 1839; repr. Toronto, 1974). Innis, Fur trade in Canada (1962). J.-C. Lamothe, Histoire de la corporation de la cité de Montréal depuis son origine jusqu’à nos jours . . . (Montréal, 1903). Lemieux, L’établissement de la première prov. eccl. B. C. Payette, The northwest (Montreal, 1964). R A. Pendergast, “The XY Company, 1798 to 1804” (phd thesis, Univ. of Ottawa, 1957). Linda Price, Introduction to the social history of Scots in Quebec (1780–1840) (Ottawa, 1981). Robert Rumilly, La Compagnie du Nord-Ouest, une épopée montréalaise (2v., Montréal, 1980); Hist. de Montréal; Papineau et son temps. Léo Traversy, La paroisse de Saint-Damase, co. Saint-Hyacinthe (s.l., 1964). Tulchinsky, River barons. M. [E.] Wilkins Campbell, The North West Company ([rev. ed., Toronto, 1973]). Marthe Faribault-Beauregard, “L’honorable François Lévesque, son neveu Pierre Guérout, et leurs descendants,” SGCF Mémoires, 8 (1957): 13–30. É.-Z. Massicotte, “Quelques rues et faubourgs du vieux Montréal,” Cahiers des Dix, 1 (1936): 105–56. “Nécrologie: madame de Rocheblave,” La Patrie, 18 déc. 1886: 4. Guy Pinard, “Montréal, son histoire et son architecture: la prison du Pied-du-Courant,” La Presse, 30 nov. 1986: A8; “Le club des ingénieurs,” 21 sept. 1986: 28, 53. Albert Tessier, “Encore le Saint-Maurice,” Cahiers des Dix, 5 (1940): 145–76.

Cite This Article

Pierre Dufour and Marc Ouellet, “RASTEL DE ROCHEBLAVE, PIERRE DE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rastel_de_rocheblave_pierre_de_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rastel_de_rocheblave_pierre_de_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Pierre Dufour and Marc Ouellet |

| Title of Article: | RASTEL DE ROCHEBLAVE, PIERRE DE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | January 2, 2026 |