Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

PIERS, HARRY, curator, librarian, naturalist, historian, and author; b. 12 Feb. 1870 in Halifax, son of Henry Piers and Janet Louisa Harrington; m. there 7 Jan. 1901 Constance Fairbanks, and they had a son; d. there 24 Jan. 1940.

The Piers family had been in Nova Scotia since 1749 [see Temple Foster Piers*]. The first of five children, Harry Piers was raised in Halifax. His father was a merchant and businessman with investments in mines throughout the province. Educated at Albro Street School and Halifax High School, in 1887 and 1888 Harry attended the newly opened Victoria School of Art and Design, where he took painting and architectural drawing but did not complete a diploma. He also studied, informally, at the Provincial Museum with its curator, David Honeyman*, expanding his scientific knowledge and learning museum methods. This work led him to hope that he would be made curator upon Honeyman’s death in 1889, but he was thwarted by a government unable, or unwilling, to fund the museum properly and pay the salary that a trained man could expect from the position, which went to Honeyman’s daughter. Instead, Piers took a series of short-term library and cataloguing positions at King’s College, Windsor, and at the Citizens’ Free Library and the Legislative Library in Halifax.

Piers really started his life’s work in 1899. The late 1880s and early 1890s had been a period of severe economic depression in Nova Scotia, but with a return to prosperity, the Liberal government of George Henry Murray* began to support cultural and social initiatives. In May 1899 Piers was appointed deputy keeper of public records, a position he would retain until 1931, when the new Public Archives of Nova Scotia was opened under the direction of Daniel Cobb Harvey*. Then, in October, Piers finally became curator of the Provincial Museum in the old Provincial Building. The public records were also housed there. His first major duty was to move the museum to the Burns and Murray Building, which the government had purchased for its growing administration. Since this structure provided space for expansion, the Nova Scotian Institute of Science was able to persuade the government to create the Provincial Science Library as an adjunct to the museum and to appoint Piers as librarian. He would hold these two positions, curator and librarian, until his death.

As a scientist, Piers was a natural historian: his work fell within the disciplines that Suzanne Zeller has called “inventory science,” which included botany, geology, and anthropology. He described his collection of Nova Scotian plants, gathered for a contest at the Halifax High School, as his first scientific work, and he retained an interest in botany throughout his life, joining both the Botanical Club of Canada (founded in 1891 by George Lawson*) and the short-lived Botanical Club of Halifax (formed in 1901). He also conducted research in entomology, ichthyology, and mammalogy, both for pleasure and for his work in the museum, but his real love, and the centre of his intellectual life, was ornithology. Learned during his teenage years on walks with Andrew Downs*, a naturalist and friend of the family, it was the topic of a number of Piers’s earliest published articles and editorial undertakings. He was perceived by a number of his correspondents as a specialist in birds; in 1891 he became an associate member of the American Ornithologists’ Union and from 1901 to 1907 he coordinated an ornithological-data-collection project through his museum.

Most of Piers’s professional time was nonetheless spent on geology and mineralogy. Honeyman had concentrated on these areas and, because the museum fell under the Department of Public Works and Mines, Piers was often called on to perform jobs not strictly related to museum work. He identified rocks and minerals for the government and private individuals, and was occasionally required to inspect mines in outlying parts of the province. In addition, he was given charge of the Mines Building at the Provincial Exhibition where, each year from 1902 to 1917, he arranged a show of the economic minerals of Nova Scotia. In order to advertise the province’s mineralogical potential more widely, the government sent him and the display to the Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition in Virginia (1907) and the Industrial Exhibition in Toronto (1908).

Piers grumbled in his diaries about this extra work. He felt he was not being paid sufficiently and, in the case of the mine inspections, he had a phobia about going underground. He particularly disliked his duties at the provincial exhibitions, which he found tedious, and they took him away for weeks at a time, requiring him to recruit his wife or one of his sisters to run the museum in his absence. But, raised with an upper-class Victorian belief in progress, natural science, and the industrial potential of Nova Scotia, he never questioned the value of the mineral exhibits. When asked to speak about the museum’s history and aims, he stressed that it was not a curiosity shop but a commercial museum, a concept that drew upon the museological ideas of George Brown Goode of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Because Piers’s scientific interests were much wider than Honeyman’s, he expanded the mandate of the museum. He brought in plants, insects, molluscs, fish, birds, and other fauna, and, even while articulating the institution’s practical use or potential, he began systematically collecting in the areas of anthropology, ethnology, and history, which had no direct commercial value.

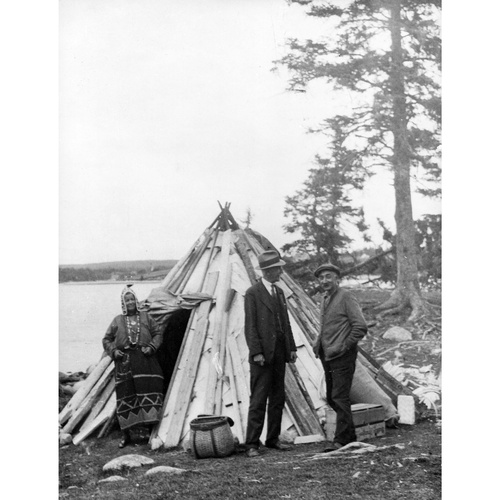

Recognizing “the gradual disappearance of old customs,” in 1901 Piers started buying and collecting Nova Scotian Micmac (Mi’kmaw) artefacts, though for the next few years this collection was so small that it remained in the “Miscellaneous” category of his annual curatorial reports. By 1909–10, however, anthropology, history, and art had all become separate categories. In 1922 the anthropological collection alone totalled 2,575 items. During the 1920s and 1930s the number of historical and artistic pieces also increased, in most years far surpassing the scientific acquisitions. By then Piers was seeking out and accessioning a wealth of oral and written accounts from such Micmac informants as Jerry Lonecloud*.

The museum’s larger mandate was partly a reflection of Piers’s own expansive interests, including a refocusing of his intellectual life over the years. This shift was a manifestation of his changing relationship to the two voluntary organizations that dominated his life, the Nova Scotian Institute of Science and the Nova Scotia Historical Society. He had been an active member of the institute from 1888, when he presented his first paper, on fish. He was elected to its council in 1891 and served as recording secretary from 1894 to 1934. Piers was aware that, during the latter part of the 19th century, the emphasis in science was moving from description and classification to theory and laboratory work. In 1896 he had a letter from a friend who hoped he was still specializing in ornithology and had not become a “devotee of the higher sciences.” Although Piers appreciated the gains being made by scientists, he was also certain that he did not like all the changes. In an address drafted in 1929 to honour Dr Alexander Howard MacKay* but never actually delivered, Piers planned to speak about how science required intensive university training and was becoming more and more isolating. He wrote in his notes that such training “puts each group off by their lonesome” and that “one group does not know the long-winded jargon of the others.” The convivial sharing of information on many topics that Piers participated in, with friends and colleagues around the province, was more to his liking.

Unfortunately for Piers, the change in scientific practice was linked to the growing split between professionals and amateurs found in many occupations. By the 1930s the institute of science was dominated by specialists with graduate degrees in laboratory and theoretical sciences. Piers, who had apprenticed in the Provincial Museum and learned his ornithology and botany while tramping through the woods, was a mere amateur by comparison. Despite his long years of service and immense amount of work in numerous disciplines, he became a secondary figure within Nova Scotia’s scientific community. Even the move in 1910 of the Provincial Museum into the new Nova Scotia Technical College, where Piers was surrounded by (and was meant to be useful to) scientists, could not sustain his reputation.

Though still the recording secretary of the institute of science, Piers recognized what was happening to his status within it. As the 20th century progressed, he noted increasingly in his diaries that he was no longer being asked to speak at its meetings and that the “Dalhousie [University]” men were dominating the institute, but he did not let any disregard slow him down. He had always been interested in the province’s past, and his prodigious research skills were as well suited to the study of history as they were to enquiry in the natural sciences. Thus, the beneficiary of Piers’s marginalization was the historical community. He had been active in the Nova Scotia Historical Society as a member and author from 1895; his engagement increased during the 1920s and 1930s. He served as vice-president in 1921 and president in 1924–27. Reports in his diaries of society meetings and projects began to take up more space than did those of the institute of science, which were relegated to mere mentions. Still, he continued to attend the institute’s meetings and in 1934–36 he was its president. Piers’s biographical studies of naturalist Titus Smith* and conchologist John Robert Willis* reflect a duality of interests, but the growth of his museum’s history and anthropology departments best underlines his shift from science to history. Indeed, after his death in 1940, many Nova Scotians remembered Piers as an historian. In an oddly complimentary way, it was his historical work, in the form of an unfinished manuscript, published posthumously, that drew critical attention. D. C. Harvey and military historian Charles Perry Stacey* both found fault with his research for his study of Halifax’s fortifications.

Piers’s diminution within the professional scientific community was mirrored by the change in his status as deputy keeper of the public records. When the public archives was opened in January 1931, Piers, who had been neither contacted nor consulted on its creation, was not even invited to the ceremony. He believed that this oversight was due to the fact that the invitation list was drawn up by members of the Dalhousie faculty and he considered it a deliberate slight to his reputation. Although he did not let his bitterness colour his relationship with D. C. Harvey, he complained in his diary. He exacted a small revenge by insisting on an official letter of request from the provincial secretary before allowing the records he had tended for 31 years to be transferred out of his care.

The institute and the historical society, though central to shaping Piers’s life, tell only a portion of his story. An industrious man, he belonged to a legion of other organizations – scientific, historical, artistic, and cultural, local, national, and international. To name but a few, he was a member of the American Association of Museums and sat as Nova Scotia’s representative on the Geographic Board of Canada (where he had succeeded A. H. MacKay). In 1901 he had married Constance Fairbanks, an accomplished author and journalist with whom he had edited a collection of poetry by Mrs William Lawson [Mary Jane Katzmann*]. He also edited Lawson’s history of local townships, the Journal of the Mining Society of Nova Scotia for 12 years, and the Proceedings of the institute of science for 8 (all published in Halifax). A commissioner of the Legislative Library, he helped complete in 1911 its cataloguing of the outstanding collection of Thomas Beamish Akins*, and he served as a volunteer trustee of the component Akins’ Library.

In religion Piers was a Sandemanian by upbringing and choice. He took to the Church of England only when the Sandemanian church folded. He enjoyed lawn bowling, walking, and painting. The only public displays of his artwork came at the Provincial Exhibition of 1882 and not again until he was in his sixties, when he had a watercolour of Hubbards’ Cove (Hubbards) in the 1933 exhibition of the Nova Scotia Society of Artists. Throughout his career he often used his artistic and design skills in his museum work, drawing or painting accompaniments to his descriptions of artefacts. As well, he was an art historian. In 1927 he published a biography of Nova Scotia portrait-painter Robert Field*. His research on the gold- and silversmiths of the province, first presented to the historical society in 1939, would be published after his death. For his service to the arts, the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design awarded him an honorary diploma in 1932. Last but not least, he was a doting father who often brought his son, Edward Stanyan Fairbanks, to work with him in the museum or took the afternoon off so that they could go fishing together. In poor health from about 1934, and increasingly unable to work, he declined quickly after his wife’s death in 1939.

Harry Piers was a complex man who must be remembered as much for what he represented as for what he accomplished. He was conservative, almost reactionary, in his dislike of change. When the government went from a ten-to-four to a modern nine-to-five day, he protested and was granted the right to set his own hours, since he was in charge at the museum. When daylight saving time was instituted in 1916, he began filling his diary with complaints that it was unnecessary to adjust the clocks and would be simpler if everyone just started their day an hour earlier. Yet, he praised the attainments of science and delighted in the progress that brought radios and automobiles into his life in the 1920s. When required, he could adapt: a natural scientist in the Victorian mould, he remade himself into an historian in the latter part of his life.

What Piers accomplished makes him remarkable. Under his care, the Provincial Museum grew from little more than an exhibit of mineralogical specimens into a full-fledged modern museum of science and history. He broadened its mandates of collection and display, and increased its holdings more than threefold. In particular, he had the foresight to embrace anthropology, ethnology, and history, thereby saving from loss much of the human history of Nova Scotia. His correspondence with scientists and historians around the world placed him within the group of scientific and cultural workers that, even across Canada, was still relatively small in the first half of the 20th century. Because he was always gathering information, writing voluminous notes, and adding to his accession records, he made the museum’s collection one of the best documented in the country. Piers created a body of knowledge that has stood the test of time. His publications on Robert Field, Halifax’s fortifications, birds and fishes, and gold- and silversmiths are still cited by scholars, while the catalogues he prepared remain a major resource for the museum’s staff and for researchers.

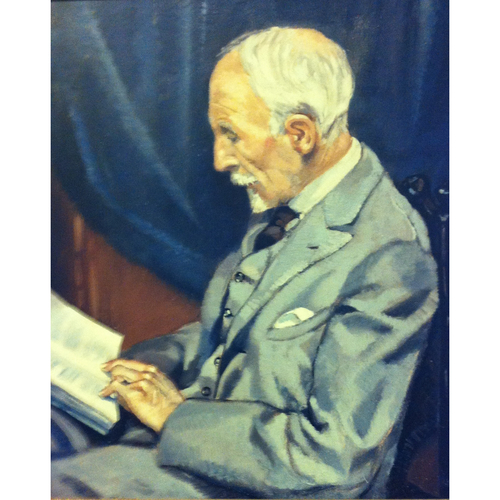

N.S. Museum (Halifax), 35.18.1 (photo of Piers showing a specimen to a museum visitor), 11 March 1935; 36.118 (photo of Piers with Susan Abram Sack and Henry Sack, a Micmac couple from whom he purchased artefacts), 13 Sept. 1935; P149.25 (portrait of Piers by LeRoy Judson Zwicker); Vert. files, Piers, Harry. N.S. Museum Library, mss, Piers papers. NSA, MG 1, vols.753—58, 758A, 1046—51, 1153A, 1464—66 (Harry Piers fonds); N-1258 (negative of subject); “Nova Scotia hist. vital statistics,” Halifax County, 1870: www.novascotiagenealogy.com (consulted 7 Nov. 2012). Lou Collins, “Piers was a devoted historian,” 4th Estate (Halifax), 21 April 1977: 13. “A bibliography of the works of Harry Piers,” in his The evolution of the Halifax fortress, 1749–1928, ed. G. M. Self et al. (Halifax, 1947), ix–xii. Canadian who’s who, 1936/37. E. D. Mak, “Nova Scotia at the Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition, 1907: excerpts from the diary of Harry Piers,” Nova Scotia Hist. Rev. (Halifax), 16 (1996), no.1: 81–90; “Patterns of change, sources of influence: an historical study of the Canadian museum and the middle class, 1850–1950” (phd thesis, Univ. of B.C., Vancouver, 1996); “Ward of the government, child of the institute: the provincial museums of Nova Scotia (1868–1951),” in Studies in history and museums, ed. P. E. Rider (Hull [Gatineau], Que., 1994), 7–32. N.S., Provincial Museum, Report on the Provincial Museum and Science Library (Halifax), 1900–11, 1931/32–43/44; Report on the Provincial Museum, Science Library, and public records (Halifax), 1922–30/31. Suzanne Zeller, Inventing Canada: early Victorian science and the idea of a transcontinental nation (Toronto, 1987).

Cite This Article

Eileen Mak, “PIERS, HARRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/piers_harry_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/piers_harry_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Eileen Mak |

| Title of Article: | PIERS, HARRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2014 |

| Year of revision: | 2014 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |