Source: Link

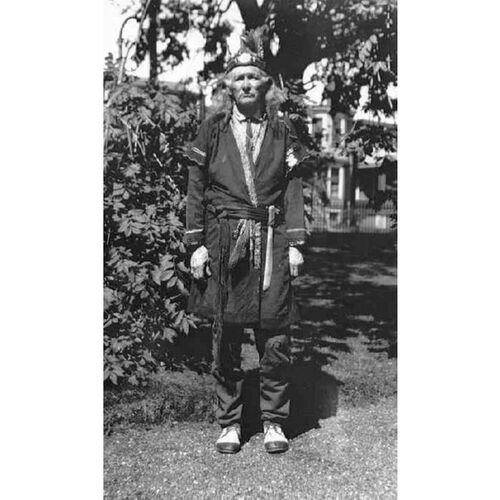

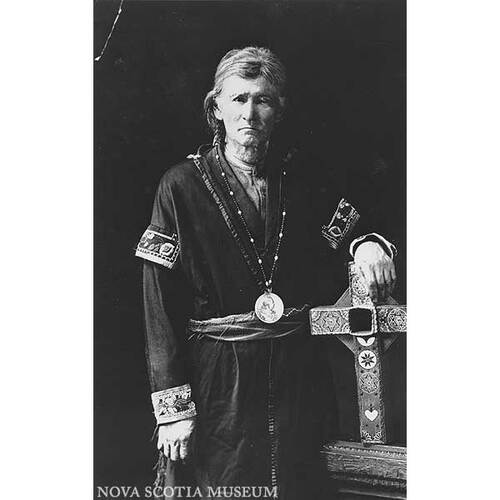

LONECLOUD, JERRY (his birth-name was Germain Bartlett Alexis and sometimes he used Jerry Bartlett; known in Micmac (Mi’kmaq) as Slme’n Laksi (Haselmah Luxcey)), guide, lumberer, showman, herbalist, Micmac (Mi’kmaw) sub-chief, and folklorist; b. 4 July 1854 in Belfast, Maine, son of Abram Bartlett Alexis of Shelburne County, N.S., and Mary Ann Toma (Thomas) of St Croix, N.S.; m. 1888 in Kentville, N.S., Mary Elizabeth Paul of Fredericton, and they had four daughters, two sons, and two children who died in infancy; he also had a son by an unknown mother; d. 16 April 1930 in Halifax.

Jerry Lonecloud was born in 1854 into a Micmac family of herbalists who travelled through British North America and the northeast United States, making and selling remedies. His father provided recipes to the bottlers of Dr Morse’s Indian Root Pills. His family canoed the Great Lakes when he was a child, and once took the Erie Canal to New York City, where they camped in an alder swamp at the site of the future Brooklyn Bridge. When the Civil War began, Lonecloud’s father joined the Union army. As one of the volunteers who tracked and captured John Wilkes Booth, Abraham Lincoln’s assassin, he went to New York in 1866 to collect his share of the reward money, and he was murdered there. Lonecloud’s mother died shortly afterwards, in Vermont, leaving him to care for his sister and two younger brothers. He got them safely home to Nova Scotia.

Jerry made a living there guiding and lumbering until a talent scout for Healy and Bigelow’s Wild West Show recruited him to return to the States early in the 1880s. He was then living at Bear River. As a so-called medicine man with Healy and Bigelow, he was given the name “Dr. Lone Cloud.” He performed as a sharpshooter, helped prepare the Kickapoo Indian Sagwa patent remedy, and peddled it as far away as South America. Eventually he left to perform with Buffalo Bill Cody’s show, but he deserted it when Cody prepared to visit England. Highlights from this part of his life, in 1885, were a visit to Niagara Falls and the funeral of President Ulysses S. Grant in New York.

After another spell with Healy and Bigelow’s outfit, Lonecloud formed his own company, the Kiowa Medicine Show, which played little towns throughout New England. It failed, but he later put together a show in Maritime Canada, giving dramatizations of Captain John Smith and Pocahontas and similar “Indian” entertainments. He married his 17-year-old co-star, Elizabeth Paul, a young Maliseet who had joined the show. “I liked her ways,” he explained. “There was no more to it. I hired her brother, and she wanted to come.” Lonecloud would continue to lecture and perform sporadically in Nova Scotia for much of the rest of his life, often assisted by his family. “I was a showman,” he would relate with pride.

In 1890 Lonecloud took Elizabeth and their children to Liscomb Mills, N.S., where he worked as a prospector, herbalist, logger, and guide to sportsmen. He came to have a comprehensive knowledge of the province, hunting all over it during the next 20 years. In 1910 an affair with a married woman in the Liscomb neighbourhood became public when she bore him a son. Separating from his wife, he moved to Halifax. There he acted as an advocate for the Micmac, writing endless letters to Indian agents in Nova Scotia and Ottawa on property rights and other matters. He was elected captain and then sub-chief for Halifax County, and became, possibly through self-appointment, “Chief Medicine Man” for the county and later for all of Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island.

While living in Halifax, he initiated the two greatest contributions of his life, both in the preservation of Micmac culture. In 1910 he met Harry Piers*, curator of the Provincial Museum, and began passing on oral histories, folk tales, and over 200 cultural and natural history specimens, including photographs, traditional clothing, birds, and plants. In addition, he made replicas of unobtainable Micmac items and, building on the work of Silas Tertius Rand*, Father Pacifique [Buisson*], and other early ethnologists, he contributed to a wider knowledge of his language by teaching Piers Micmac place-names and vocabulary. Piers, who had many Micmac informants, frequently commented in his notes on Lonecloud’s broad intelligence, how he was “possessed of a fund of information. . . . I always found him frank, loyal, and he had a razor-keen sense of humour. He was familiar with every brook, river and lake from Windsor to Canso.” In return, Piers, who erroneously believed that Lonecloud’s first name derived from Jeremiah, drafted some of his formal correspondence, including a number of petitions to the Department of Indian Affairs.

At some point before 1917 Lonecloud’s wife and family rejoined him. They lived in a Micmac shantytown at Tufts Cove, northwest of Dartmouth across the harbour from Halifax. Tragedy struck on 6 December of that year, when the ammunition ship Mont Blanc exploded, destroying much of Halifax-Dartmouth and killing Lonecloud’s daughters Rosie and Hannah. His possessions gone and blind in one eye, Lonecloud was hard put to support his family. He made baskets, snowshoes, moose calls, and caps for sale, and until 1929 he continued to travel the province collecting items to sell to the museum. In April 1930 he became ill and died; he was buried in St Peter’s Roman Catholic Cemetery in Dartmouth.

Lonecloud left an even greater legacy than the material he passed on to Piers. Between 1923 and 1929 he had given a series of interviews, unpublished until 2002, to reporter Clarissa (Clara) Archibald Dennis of Halifax. She recorded his life story, thus creating the earliest known Micmac autobiography. Lonecloud poured out a lifetime of recollections, tales, and customs in a style that was folksy with flashes of poetry. In Lonecloud’s story of creatures before the Flood, Pollywog explained in verse his presence beside a lake: “I am going down / Into the water / Where there are no stars.” Dense with data and vivid with life, this material is an enormous contribution to our knowledge of Micmac culture since much of what Jerry Lonecloud told Dennis is not available from any other source. Ethnographer of the Micmac nation could rightly have been his epitaph, his final honour.

Photographic portraits of Jerry Lonecloud, and portraits of others collected by him, are found in “The Mi’kmaq portraits coll.,” comp. R. H. Whitehead: museum.gov.ns.ca/mikmaq/index.htm (consulted 3 Jan. 2005). Another photograph of Lonecloud is in the collections of the Geological Survey of Canada (Ottawa), N-24253 (Mi’kmaq at a geological congress), 21 July 1913. The Harry Piers papers are in the N.S. Museum Library (Halifax).

N.S. Museum, Hist. section, Mi’kmaw heritage resource files, Ruth Legge to Ruth Whitehead, taped interview and transcript, September 1995. “Jerry Lonecloud and the Nova Scotia Museum: information acquired by the Nova Scotia Museum from Jerry Lonecloud, 1910–1930,” ed. R. H. Whitehead: museum.gov.ns.ca/resources/lonecloud.htm (consulted 3 Jan. 2005). The old man told us: excerpts from Micmac history, 1500–1950, comp. R. H. Whitehead (Halifax, 1991). R. H. Whitehead, Harry Piers papers in the Nova Scotia Museum (3v., Halifax, 2003); Tracking Doctor Lonecloud: showman to legend keeper, including the memoir of Jerry Lonecloud (Fredericton and Halifax, 2002).

Cite This Article

Ruth Holmes Whitehead, “LONECLOUD, JERRY (Germain Bartlett Alexis, Jerry Bartlett) (Slme’n Laksi, Haselmah Luxcey),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lonecloud_jerry_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lonecloud_jerry_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ruth Holmes Whitehead |

| Title of Article: | LONECLOUD, JERRY (Germain Bartlett Alexis, Jerry Bartlett) (Slme’n Laksi, Haselmah Luxcey) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 28, 2025 |