Source: Link

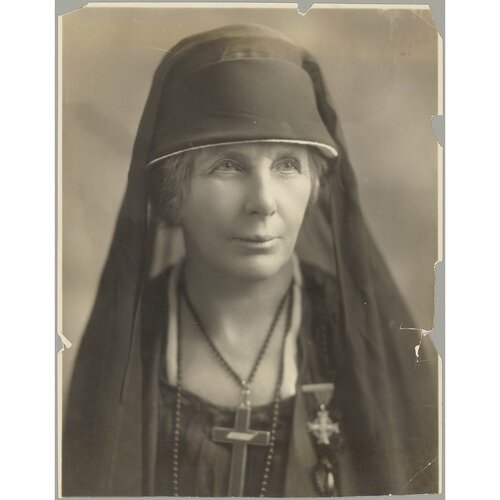

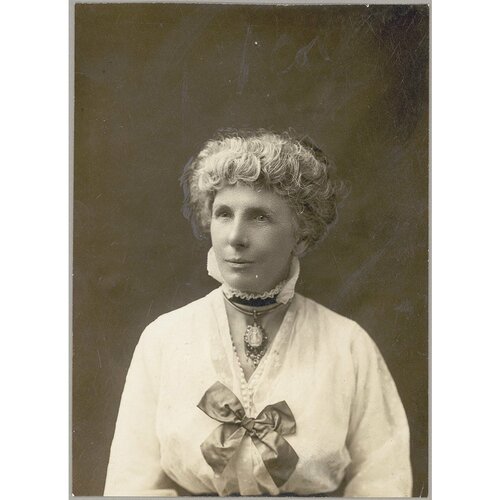

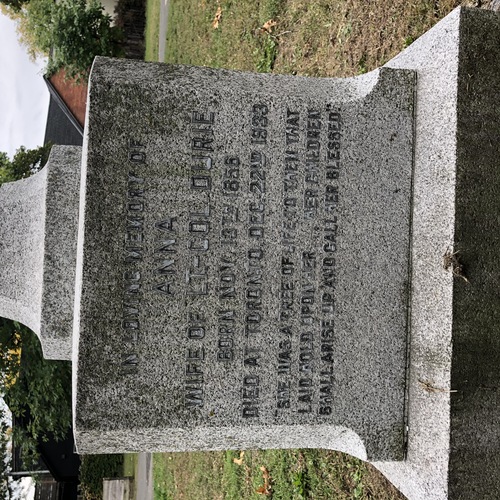

PEEL, ANNA BELLA (Durie), war mother and author; b. 13 Nov. 1856 in Thornhill, Upper Canada, second daughter of John Alexander Peel and Frances Burgess; m. 8 Oct. 1880 William Smith Durie* in Albany, N.Y., and they had a son and a daughter; d. 22 Dec. 1933 in Toronto.

Anna Peel’s parents had emigrated from County Armagh (Northern Ireland). She and her elder sister, Emily Ruth, were raised in New Orleans, where the Peels may have already been living before Anna’s birth. Her mother probably travelled north to Upper Canada to be with relatives during her confinement. As a young girl, Anna witnessed the siege and capitulation of New Orleans in 1862 during the Civil War. According to family records, her father had been a newspaper editor who after the war became a successful merchant. Though never wealthy, he was able to buy a large home, possibly with money from his wife’s family, on the outskirts of the city and was noted as a “man of culture and refinement.”

Like many other residents, the young sisters and their mother left New Orleans during the “sickly season,” in their case to spend summers in Canada. In 1870 Anna and Emily were taken to Europe to complete their education. Over the next three years they studied painting, music, and languages and visited the great art galleries and opera houses of France, Belgium, and Germany. In Paris Anna saw the wounded of the Franco-German War being brought into the city on flatcars and experienced first-hand the chaos that followed the rise of the Commune when the family carriage was surrounded by an angry mob.

Her mother became ill in 1873; she died aboard ship and was buried in Queenstown (Cobh, Republic of Ireland). John Peel sold the family mansion in New Orleans, probably to effect a division of assets among the heirs. Two years later Anna sued her father, who had suffered a reversal of fortune, claiming that he had “interfered” with the administration of her mother’s estate. This action may have been intended to ensure that her inheritance (just under $25,000) was not commingled with any business debts he incurred.

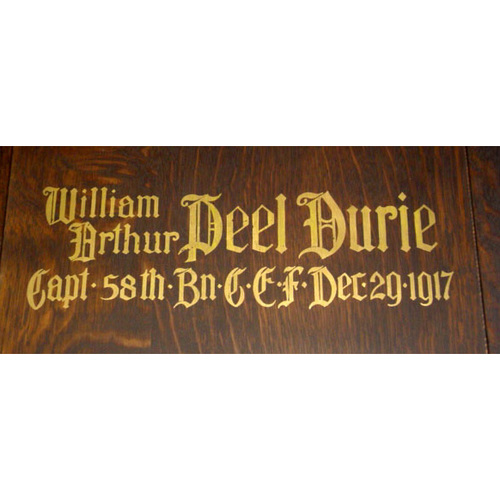

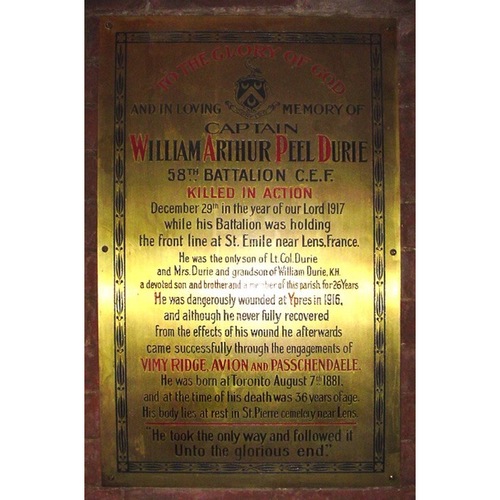

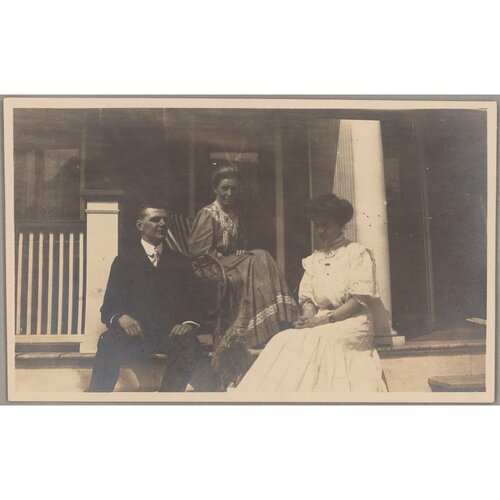

In 1877, at age 21, Anna became engaged to William Smith Durie, deputy adjutant-general of Military District No.2 (Toronto and central Ontario) of the Canadian militia, a man 43 years her senior. They had probably met in Thornhill, where his family had property. Durie was forcibly retired from army service in 1880, the year of his marriage, and to his great indignation, he received two years’ pay but no pension. Although he had spent much of his personal fortune improving Ontario’s volunteer militia, he went ahead with plans to build a grand home for his bride on Spadina Road just north of Toronto, on a site overlooking the city. He named it Craigluscar after the Durie estate near Dunfermline, Scotland. The couple had two children, William Arthur Peel (known in the family by his second name), born in 1881, and Helen Frances, who followed two years later. The Duries’ circle encompassed many of Toronto’s elite, including judge and politician Adam Wilson*, army officer William Dillon Otter*, banker and philanthropist Byron Edmund Walker*, and their wives.

William Durie died less than five years after the marriage, and by this time money was scarce for the young widow. But Anna was sure of her family’s social superiority and determined to save its members from what she called “the encroachment of Main Street.” She ignored tradesmen’s bills and mortgage payments to send both children to private schools, Arthur to Upper Canada College and Helen to Bishop Strachan. Fifteen acres of Durie land west of Toronto were confiscated by the city in 1893 for unpaid taxes, and Anna was forced to sell the family home two years later to prevent foreclosure. The shy, obedient Arthur struggled at school, yet Anna persisted in her belief that her son was destined for greatness. He joined the Traders’ Bank of Canada (acquired by the Royal Bank of Canada in 1912) as a “junior” and eventually bought a small, semi-detached house on St George Street for his mother and sister.

In 1915, after the outbreak of World War I, Arthur, who was already an officer in the 36th (Peel) Regiment, went overseas as a lieutenant with the 58th Infantry Battalion in November. Anna, now almost 60 years old, soon followed. Wives and children often did so in wartime; for a mother to trail after an adult son was unusual. She took up residence in London and relentlessly petitioned British, French, and Red Cross officials to allow her to volunteer as a nurse or for any other task on the Western Front. They refused, but she remained in England for much of the war, active with the Red Cross and financed by Arthur’s army pay, while Helen, now an English teacher at Jarvis Street Collegiate Institute, stayed in Toronto.

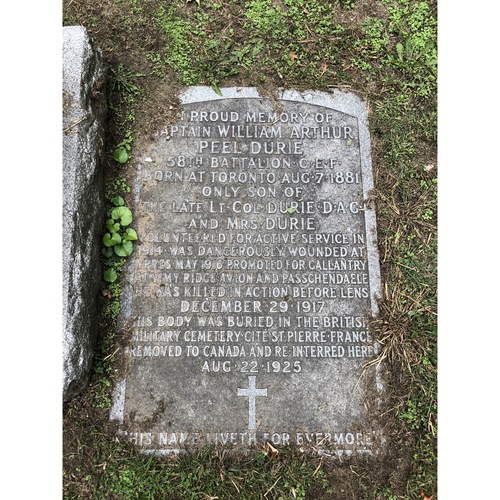

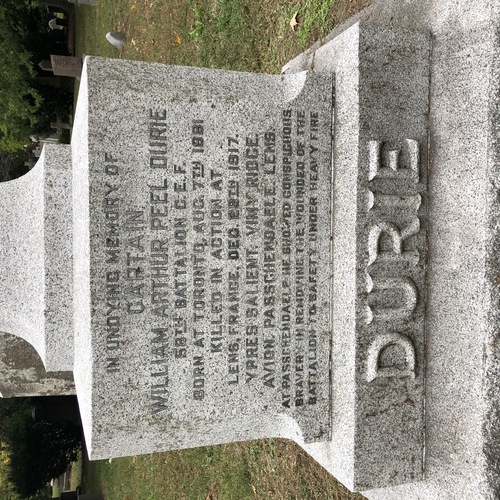

In May 1916 at Ypres (Ieper), Belgium, Arthur was seriously wounded in the right shoulder and lung and soon became “dangerously ill.” After convalescing in Britain, he returned to the front, though he later suffered trench fever and neurasthenia (shell shock). Without his knowledge, Anna wangled an interview with Canada’s minister of militia and defence, Sir Samuel Hughes*, and secured her son a staff position. He refused to accept it, but she was undeterred. Her connections and dogged persistence later snared Arthur administrative jobs in England and France; these he also declined. His letters to Anna and Helen track his growing independence. Bolstered by allegiance to his men and fellow officers, he was able to slip from his mother’s stifling emotional embrace. He told her that, despite any infirmities, he would remain with his battalion, and when the war was over, he would not go back to the bank. Then on 29 Dec. 1917 he was killed by mortar fire near Lens, France. At the time Anna was crossing the Atlantic to visit her daughter in Canada. She learned of his fate only when she stepped off the train at the North Toronto Station.

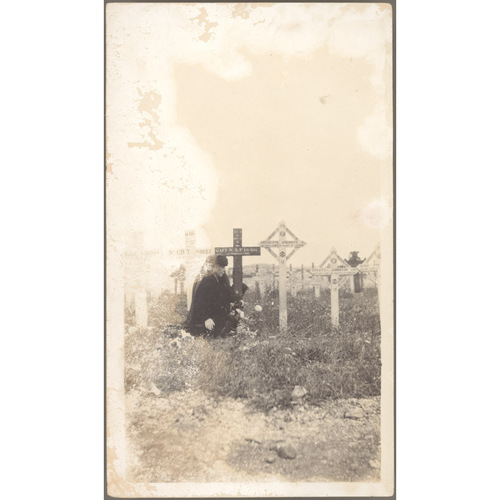

Initially, she seems to have accepted her son’s interment overseas, probably with the belief that it would be temporary; in 1918 she wrote that “with their comrades in arms our heroes sleep in an enchanted ground.” But after the conflict was over, she became increasingly preoccupied with bringing his body home. The Great War had cost the Allied forces over 5 million lives, including those of roughly 60,000 Canadians, far too many to allow for repatriation of their remains, even if they could be conclusively identified. In 1915 Fabian Arthur Goulstone Ware, founder of what would become the Imperial War Graves Commission, had argued that officers “in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred will tell you that if they are killed [they] would wish to be among their men.” Another concern was that only the well-to-do would be able to bring their loved ones back. It was eventually decided that soldiers of the British empire would be left where they had been buried, “facing the line they gave their lives to maintain.” Objections were many, but as time passed and the IWGC cemeteries blossomed, arguments fell away. Anna, however, would not be silenced. Petty rules, necessary for the common soldier, did not apply to a Durie. She had lost her son when he went to war, and by 1920 she was determined to regain both his body and his legacy.

She petitioned Canadian officials, including the current minister for the militia, Hugh Guthrie, for permission to return the remains to Canada at her own expense, and even ambushed Prime Minister Arthur Meighen* when he visited the King Edward Hotel in Toronto. It was all to no avail. So in June 1921 Anna and Helen went to France. Despite attempts by local IWGC officials to restrain this “quite unreasonable” woman who “has practically lost her senses on this one subject,” Anna and her daughter, aided by two local men, exhumed Arthur’s blanket-wrapped corpse from Corkscrew British Cemetery, near Loos-en-Gohelle, on the night of 30 July. However, when the body, now placed in a zinc-lined coffin, was hoisted onto a waiting cart, the horse shied and snapped the shafts, the broken wood piercing the animal’s side. The remains in the new casket were returned to the grave.

Four years later the two women tried again. In February 1925 Anna learned that those interred at Corkscrew had been moved to the Loos British Cemetery nearby, seemingly confirming her worst fears that her son would lie in an unmarked site. Late on 25 July hired men forced open one end of the coffin and dragged out what survived of Arthur’s corpse, leaving behind fragments of bone and clothing. The body was then smuggled back across the Atlantic as luggage. For three days it lay “in state” in the front room of the St George Street house, before being buried on 22 August in the family plot in St James’ Cemetery.

France was eager to prosecute, but British and Canadian authorities were fearful of rousing dormant resentment among the general populace. An internal IWGC report noted that “it is the view of those familiar with the case that any reopening by legal process will result in more harm than good.” The Duries’ was not the only attempt that had been made by a Canadian family to repatriate a loved one’s remains. In 1919, with the consent of the prefect of Pas-de-Calais, France, the body of Major Charles Elliott Sutcliffe was moved from its resting place at Épinoy to a private vault close by, and it was eventually reburied in Lindsay, Ont. And in May 1921, after being refused permission by the IWGC, the father of Private Grenville Carson Hopkins took his son’s corpse from a cemetery in Belgium to a mortuary in nearby Antwerp, but it was recovered before it could be shipped to Canada, and those involved were brought to trial.

Anna had written what was probably her first poem, “A soldier’s grave in France,” while visiting Arthur’s original burial site in 1919. She went on to publish a collection, Our absent hero: poems in loving memory of Captain William Arthur Peel Durie, 58th Battalion, C.E.F. (Toronto), a year later. Not content to describe a man whose true bravery consisted in returning to an overwhelming task in appalling conditions, she remade him through her writings, telling instead of an aristocratic hero and his daring deeds. This mythologizing of the conflict reflected a wider response to World War I as families struggled to give meaning to the loss of their loved ones. Her novel John Dangerfield’s strange reappearance (Toronto, 1933) portrays a valiant son who comes back from death at the front to smite those who have conspired against his family, and a daughter who has married an English lord and lives in a stately home with two perfect children. Anna contributed prose and poetry to the Mail and Empire and the Canadian Magazine, read her work on local radio, and became involved in the Canadian Authors Association. Wolfe and other poems (Toronto) appeared in 1929; she later converted the title piece into a play, but it was never staged.

In later life genealogy became a passion as Anna researched every remote connection of her husband’s family to Scottish nobility. In 1927 she and Helen travelled to Dunfermline Abbey to visit the tomb of Abbot George Durie, who had died in 1577, and were presented to King George V and Queen Mary at Holyrood Palace in Edinburgh. No evidence of any interest in her own ancestors appears in her papers. In fact, her disparaging remarks about those “in trade” point to a certain distancing of herself from the Peel connection. An Anglican, she was active in St Thomas’s Church in Toronto, where she had earlier installed a plaque to Arthur’s memory. She also served as president of the Canadian Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and as vice-president of the Conservative Women’s Club. She was made a life member of the Canadian Red Cross for her wartime services.

Anna Durie succumbed to cancer in December 1933 at the age of 77. Her daughter, Helen, never married. They are buried next to William and Arthur in St James’ Cemetery. An eight-foot cross of sacrifice marks Arthur’s grave, but no Duries remain to visit the family plot.

Eleven of Anna Bella Peel Durie’s poems have been reprinted in Canadian poetry from World War I: an anthology, ed. Joel Baetz (Toronto, 2009). A fuller account of her story is presented in the author’s “The family plot,” Toronto Life, November 2001: 75–98, and her partly fictional The invisible soldier: Captain W. A. P. Durie, his life and afterlife (Toronto, 2004), both published under the name Veronica Cusack.

AO, RG 80-8-0-1410, no.7616. City of Toronto Arch., Fonds 1065. Commonwealth War Graves Commission: www.cwgc.org (consulted 6 April 2011). Commonwealth War Graves Commission Arch. (Maidenhead, Eng.), corr. LAC, R14423-0-6; RG 150, Acc. 1992–93/166, box 2775-5. Royal Bank of Can. Arch. (Toronto), personnel records. Veterans Affairs Can., “Canadian virtual war memorial”: www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/memorials/canadian-virtual-war-memorial (consulted 25 Feb. 2011). Toronto Daily Star, 22 Aug. 1925. Philip Longworth, The unending vigil: a history of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, 1917–1967, intro. Edmund Blunden (London, 1967). K. R. Shackleton, Second to none: the fighting 58th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (Toronto, 2002). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell). J. [F.] Vance, “Battle verse: poetry and nationalism after Vimy Ridge,” in Vimy Ridge: a Canadian reassessment, ed. Geoffrey Hayes et al. (Waterloo, Ont., 2007), 265–77; Death so noble: memory, meaning, and the First World War (Vancouver, 1997) (electronic suppl. to chap.2 at www.ubcpress.ca/books/supplements/death2.html).

Cite This Article

Veronica Maddocks, “PEEL, ANNA BELLA (Durie),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/peel_anna_bella_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/peel_anna_bella_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Veronica Maddocks |

| Title of Article: | PEEL, ANNA BELLA (Durie) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2016 |

| Year of revision: | 2016 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |