Source: Link

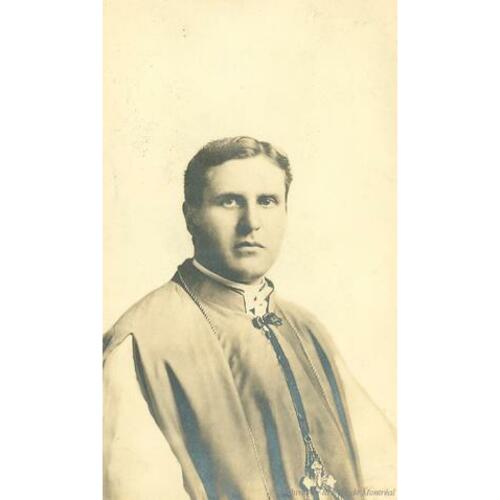

O’LEARY, HENRY JOSEPH, Roman Catholic priest and archbishop; b. 13 March 1879 in Richibucto, N.B., third of the four sons of Henry O’Leary* and his second wife, Mary O’Leary; half-brother of Richard O’Leary; d. 5 March 1938 in Victoria and was buried in St Joachim’s Cemetery, Edmonton.

Of Irish birth, Henry Joseph O’Leary’s father emigrated to New Brunswick in the 1850s. In Richibucto he became a successful businessman in the fish-canning and lumber trades, and he was also active in provincial politics. After elementary schooling, Henry attended the College of St Joseph in Memramcook. He graduated with a ba in 1897, taking the first prize in five of the six courses in the final year of the Philosophy program. A fellow student remembered him as an athlete, a practical joker with a keen sense of humour, and a “great talker.” Like his elder brother Louis James, O’Leary decided to enter the priesthood. Following a year of study at the Séminaire de Philosophie in Montreal, he enrolled at the Grand Séminaire there. He was ordained on 21 Sept. 1901 in Richibucto. Because of his outstanding academic record, his ecclesiastical superiors sent him to Rome, where he quickly earned three doctorates, in philosophy, theology, and canon law. He also studied at the Sorbonne in Paris.

O’Leary returned to New Brunswick in 1905, by this time fluent in three languages. After serving Chatham and other communities on the north shore of the province, in 1907 he was appointed parish priest of Sacred Heart in Bathurst and in 1908 vicar general of the diocese of Chatham. The following year, because of his connections in the Vatican, he was sent back to Rome by Archbishop Edward Joseph McCarthy of Halifax as part of a campaign by the local hierarchy to ensure that anglophones, and particularly the Irish, remained dominant in the episcopate of the Maritime provinces. McCarthy complained to Toronto archbishop Fergus Patrick McEvay* of being “exposed to the volleys of shot and shell from the French line of fire whenever there is a mitre waiting for a head to fit it; or a question of creating a new diocese.” Representation in Rome was necessary, he believed, “unless we are to allow the Acadians to have their own way, and utterly neglect our own various interests.” While abroad, O’Leary would also serve as agent for McEvay and Archbishop Charles Hugh Gauthier* of Kingston, Ont. Although the group had some success in influencing appointments, such as the elevation of Michael Francis Fallon to the see of London, McCarthy was frustrated in his hope of ensuring Irish hegemony in Atlantic Canada. By 1920 there would be Acadians in charge of the sees of Saint John [see Édouard-Alfred Le Blanc] and Chatham, and in 1936 the archdiocese of Moncton would be founded under Louis-Joseph-Arthur Melanson*.

Named bishop of Charlottetown on 27 Jan. 1913, in succession to James Charles McDonald*, O’Leary was consecrated on 22 May in Bathurst. His appointment was a partial triumph for the Irish clergy of the diocese, who had long complained of Scottish ecclesiastical domination there and wanted a local Irish priest to be made bishop. After his arrival in the Prince Edward Island capital five days later, O’Leary was installed in the pro-cathedral; his cathedral, St Dunstan’s, had been destroyed by fire in March. He set himself to rebuilding the church and restoring the bishop’s palace, which had also been damaged, an endeavour that took up much of his time on the Island and occupies the greater part of his diocesan correspondence. Interested in every detail from the stonework to the door hinges, he insisted that no decisions about the cathedral be taken in haste. Once the basement was completed in 1914, services began to be conducted there. The fully reconstructed cathedral would not be opened until 24 Sept. 1919. The bishop took a similar interest in the building of churches outside Charlottetown, concerning himself with both the designs and the materials employed.

His other main focus was the all-male diocesan college, also named St Dunstan’s, which had been launched in 1855 by Bishop Bernard Donald Macdonald*. In dealing with the institution O’Leary knew a number of disappointments, largely owing to lack of funds. Not only was he unable to introduce teacher-training and agricultural programs, but his plans for establishing a missionary college also came to naught, a dismaying failure given the Island’s reputation for nurturing religious vocations. He was successful, however, in persuading the government of John Alexander Mathieson* to accord the college degree-granting powers in 1917. (Since the college lacked adequate professorial staff, these powers would not be used until 1941.) O’Leary also oversaw some expansion of the institution, which had but one building. On 25 Sept. 1919 Dalton Hall, a residence for which businessman Charles Dalton had provided the financing, was officially opened (though unfinished) to welcome a rebounding number of students after World War I. That year O’Leary undertook the first fund-raising drive for the university and managed to obtain pledges of $40,000. His aim had been to erect a science building but the subscriptions were insufficient.

O’Leary had some success in enhancing diocesan resources in other ways. Although he tried, but failed, to attract a religious order of men to the Island, he was able in 1916 to establish a local community of nuns, the Sisters of St Martha, initially intended for domestic service at both the college and his residence. That the Island – “this soil so fertile in vocation” – was forced to import nuns for diocesan work was, he thought, “a great pity.” His achievement was largely thanks to Mother Mary Stanislaus [Mary Ann MacDonald*], head of the Marthas in Antigonish, N.S., who in 1915 agreed to take postulants from the Island to train at the mother house and who accompanied them back the following year to become the first superior general of the congregation in Prince Edward Island. The bishop believed that the congregation “would rapidly increase and multiply,” as indeed it was to do.

Among the other Roman Catholic institutions that O’Leary guided and expanded were the Charlottetown Hospital, established by Bishop Peter McIntyre* in 1879, and St Vincent’s Orphanage, which had been founded in 1910. The orphans’ home acquired a new building in 1914 and at the bishop’s urging the hospital added a maternity ward in 1918 and a school of nursing two years later. O’Leary was active in the war effort, asking his clergy to volunteer for the Canadian Chaplain Service [see John Macpherson Almond] and urging Island Catholics to enlist and to support various patriotic funds. He initiated a campaign to have Catholics pledge to abstain from alcoholic beverages for the duration of the conflict, exhorting his clergy to impress upon their parishioners that total abstinence, though now a national duty, was desirable at all times. He took a firm line with intemperate priests, forcing one repeat offender to resign and sending others away for a drying-out period.

In 1920 O’Leary was made archbishop of Edmonton, to succeed the late Émile-Joseph Legal*. “From the human standpoint” the transfer was, he said, “a most disagreeable one.” He was replaced in Charlottetown by his brother Louis, formerly auxiliary bishop of Chatham, an outcome that “greatly tempered” his chagrin at leaving the diocese. Appointed on 7 September, O’Leary arrived in Edmonton in December and was installed in St Joachim’s Church on the 8th. He was welcomed by the Edmonton Journal as “an eminent theologian, a priest of profound sanctity and great charity, and a man of energy, tact and ability.” His appointment, following upon the nominations of John Thomas McNally* and Alfred Arthur Sinnott* (both Islanders of Irish descent) to the new dioceses of Calgary in 1913 and Winnipeg in 1915, was intended by Rome to continue to broaden the appeal of the Catholic Church on the prairies, hitherto dominated by French-speaking clergy.

In Edmonton, O’Leary was quick to praise the pivotal role that French clergy had had in the archdiocese and expressed his pleasure at finding himself again in a “French Canadian milieu,” marked by “faith and piety.” The need for English-speaking priests was, however, clear: a diocesan census in 1920 showed that the Catholic population of greater Edmonton was only 38 per cent francophone. As the archbishop of Westminster, Francis Alphonsus Bourne, had commented at the International Eucharistic Congress in Montreal in 1910, “No one can close his eyes to the fact that in the many cities now steadily growing into importance throughout the Western Provinces of the Dominion, the inhabitants for the most part speak English as their mother tongue, and that the children of the colonists who come from countries where English is not spoken will none the less speak English in their turn.” “The power, influence, and prestige of the English language,” Bourne believed, must “be definitively placed upon the side of the Catholic Church.” O’Leary subscribed to this view, and accordingly favoured anglophone priests over francophones. Aware of the delicate position in which he found himself because of the cultural rivalries in his archdiocese, he was attentive to all members of his flock, giving sermons in parishes within and outside his see city, attending gatherings of local ethnic and other associations, and blessing new endeavours at the parish level. In the case of the French Canadian community, he was active in meetings of the Association Canadienne-Française de l’Alberta and in Saint-Jean-Baptiste day celebrations throughout his archdiocese.

The urgent need in O’Leary’s new charge was for a sufficient number of priests overall, “men to cover this vast territory where souls are being lost to the faith by the thousands,” as he commented to Bishop James Morrison* of Antigonish in 1922. The needs of the fast-growing immigrant population and earlier settlers were not being met: in 1921 there were 55 parishes without resident priests. According to one of his clerics, Peter Felix Hughes, “he visited every diocese in Eastern Canada, and even crossed the Atlantic to beg for priests.” Over the course of his archiepiscopate O’Leary would bring in at least 75 clergymen and seminarians, many of them, like Hughes, from Prince Edward Island. Among those of his co-religionists whom O’Leary worried about particularly were the Ukrainian Eastern-rite Catholics (also known at the time as Ruthenians), who had been converting to Protestantism or Russian Orthodoxy. “We are having a very hard fight here to save the Ruthenians,” O’Leary wrote to his brother Louis in 1925. Although ultimately unsuccessful, he at least helped stem the tide of their conversion.

There was much to accomplish in other ways. “I am very busy out here,” he wrote to his half-brother Richard in 1922, “with lots to do and little, very little to do it with. I have, at the present time, to see to the building of a High School, a University College, a Cathedral and many other things.” Edmonton was in fact without a cathedral when O’Leary arrived. In 1924 work was renewed on St Joseph’s Church, which Legal had begun to build, in a different location, ten years earlier. When its basement was finished in 1925, the church was opened for services. O’Leary chose St Joseph’s as his cathedral. But because of the Great Depression, and then World War II, the large stone church planned in 1920 would not be completed until 1963. In addition to the church, a new residence for the archbishop was erected, in 1928. O’Leary also expanded the separate-school system, which on his arrival consisted in Edmonton itself of eight elementary schools and just one (co-educational) high school, as well as some private institutions run by religious orders. By the late 1920s five new schools had been opened in the city, including separate high schools for boys and girls.

The archbishop took a great interest in Catholic students at the University of Alberta, who were, he said, “losing their faith as fast as they can.” In 1926 he and others petitioned the Legislative Assembly to authorize a Catholic college that would be affiliated with the university, an idea that had first been proposed by Legal. The university, under President Henry Marshall Tory*, offered land for the institution, as it had with other denominations desiring affiliated colleges. Assisted by Father John Roderick MacDonald*, O’Leary persuaded the Carnegie Corporation of New York to contribute $100,000 if he raised an equal sum by 1 Jan. 1925. He was able to do so with the help of Bishop John Thomas Kidd* of Calgary and Alfred James Dooner*, named Brother Alfred (businessman Patrick Burns contributed $20,000). In September 1927 St Joseph’s College was opened under the Brothers of the Christian Schools, whose services O’Leary had managed to obtain. His dream of having a Catholic women’s college at the university faded away, however, with the Carnegie Corporation expressing interest but declining financial support. Nor was he able to persuade the corporation to provide funds to discharge the debt of the men’s college. The archbishop also promoted the establishment of St Joseph Seminary, which was intended to develop a local clergy and which, like the college, began accepting students in September 1927. Previously, the Franciscans had expanded the opportunities to follow religious vocations by establishing St Anthony’s Seraphic College, for which the archbishop laid the foundation stone in 1925.

Beyond the educational bodies that he fostered, O’Leary oversaw the erection of numerous parishes, churches, chapels, and convents, doubled the number of hospitals and hospices, and founded many other institutions throughout his archdiocese. His efforts earned him the nickname “the Builder.” In Edmonton itself, a new wing was added to the Misericordia Hospital, which was run by the Sisters of Miséricorde. With the archbishop’s encouragement an orphanage for boys, St Mary’s Home, was opened in 1923 by the Sisters of Providence of St Vincent de Paul. In the same year this community was able to acquire a larger property for Rosary Hall, its women’s hostel. At O’Leary’s request the same order established, in 1927, a home for the aged, the House of Providence, that would eventually become St Joseph’s Auxiliary Hospital. O’Leary assisted the Sisters of the Good Shepherd by introducing them to James Daniel O’Connell*, who provided funds to enable them and the orphaned girls for whom they cared to move in 1928 into more capacious quarters, the O’Connell Institute. He also gave encouragement to the Catholic Women’s League [see Katherine Angelina Hughes*], believing that “it is the Catholic woman who is the paramount influence in the Catholic home,” and therefore in the school, and that she also had “important duties in the social order.” The league ran a hostel in Edmonton and raised money for many other diocesan institutions. O’Leary served for a time as its honorary chaplain. Besides the Christian Brothers, O’Leary brought a number of religious orders into the diocese, including the Redemptorists, the Sisters of Charity from both Halifax and Saint John, the Sisters of St Joseph, the Sisters Adorers of the Precious Blood, the Franciscan Sisters of the Atonement, and the Sisters of Service. He also launched, in 1921, a diocesan newspaper, the Western Catholic, to report on religious developments and explain the church’s teachings.

The Great Depression limited O’Leary’s ability to further advance his diocese. He lost his brother Louis to a heart attack in 1930 and his half-brother Richard two years later. Also in 1932 his protégé James Charles McGuigan*, who had accompanied him from Charlottetown as his secretary and was then archbishop of Regina, suffered an upsetting breakdown from overwork. Towards the end of 1934 O’Leary’s own health began to deteriorate, apparently as the result of an artery that was not functioning properly, and he was in hospital in January 1935. “Strange case,” reported Archbishop Peter Joseph Monahan* of Regina in July. “He does not want to see any body, thinks that it is all up with him ..[.] does not even want to go out for a drive in his car.… He looks better than for years past, and yet is nervous.” O’Leary was laid even lower by a heart attack later that year, and he was an invalid thereafter.

O’Leary died in Victoria in 1938, just eight days short of his 59th birthday, while returning to his diocese from Hawaii, where he had gone to recruit his health. He was succeeded by his recently appointed coadjutor, John Hugh MacDonald*, who paid tribute to “his brilliant intellect, his prodigious energy, his innate modesty despite his princely manner, his sense of humor, his sympathetic understanding of social and individual problems, [and] his ability to inspire others with courage and enthusiasm.” O’Leary’s work for the church had been recognized in 1926 when he was made an assistant at the pontifical throne. “His role was cast in too restricted a sphere,” one Edmontonian said. “He should have been a cardinal and he should have lived in Rome.”

The DCB/DBC is grateful to the following for assistance in the preparation of this biography: Luke J. Baird, Gerhard Ens, John Fontaine, G. Edward MacDonald, Mark G. McGowan, and Kenneth J. Munro.

Arch. of the Diocese of Charlottetown, H. J. O’Leary corr., esp. O’Leary to St Dunstan’s building committee, 8 May 1913; O’Leary to Sister Mary Stanislaus, 7 Jan., 12 April 1915; O’Leary, circular to his clergy, 29 April 1915; O’Leary to A. A. Sinnott, 24 June 1920; O’Leary to Pietro Di Maria, 13 Aug. 1920. Arch. of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto, ME (McEvay papers), AF04.06, AF04.40, AF04.41, AF04.45, AF04.47, AF04.64; FA01.24, FA01.62, FA01.63A, FA01.63B, FA01.66C; FA02.01, FA02.07A; FA02.80, FA02.81; FA13.114A-B. BCA, GR-2951, no.1938-09-541538. Catholic Archdiocese of Edmonton Arch., H. J. O’Leary papers, esp. ARCAE 97-1-2, 97-2-1, 97-3-20 (1), 97-3-20 (7), 97-3-20 (8), 97-3-29. Edmonton Journal, 6 Dec. 1920: 1, 15; 8 Dec. 1920: 1, 15; 7 March 1935: 1–2. Lethbridge Herald (Lethbridge, Alta), 18 Feb. 1925: 7. J. R. Beck, To do and to endure: the life of Catherine Donnelly, Sister of Service (Toronto, 1997). John Blue, Alberta, past and present, historical and biographical (3v., Chicago, 1924), 2. Canada ecclésiastique, 1920–38. The Catholic Church in Prince Edward Island, 1720–1979, ed. M. F. Hennessey (Charlottetown, 1979). Catholic Health Assoc. of Alta, “The bold journey, 1943–1993: an Alberta history of Catholic health care facilities and of their owners”: 135, 149–50, 154, 200: www.chac.ca/about/history/books/ab/Alberta_The%20Bold%20Journey%201943-1993.pdf (consulted 5 Feb. 2019). Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer, “Edmonton – St. Alphonsus parish, 1924–1999”: redemptorists.ca/archives/alberta (consulted 5 Feb. 2019). “CWL [Catholic Women’s League] history in Edmonton archdiocese, 1912–1962”: www.e.cwl.ab.ca/index_files/cwledmontonhistory.pdf (consulted 5 Feb. 2019). T. J. Fay, A history of Canadian Catholics: Gallicanism, Romanism, and Canadianism (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2002). John Gilpin, The Misericordia Hospital: 85 years of service in Edmonton (Edmonton, 1986). E. J. Hart, Ambition and reality: the French-speaking community of Edmonton, 1795–1935 (Edmonton, 1980). Norma Johnson, “Biography of the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity, 1912–2012”: caedm.ca/Portals/0/documents/virtual%20exhibits/2013-11-24_SistersofCharity.pdf (consulted 30 July 2018). G. E. MacDonald, The history of St. Dunstan’s University, 1855–1956 (Charlottetown, 1989). Heidi MacDonald, “The social origins and congregational identity of the founding sisters of St. Martha of Charlottetown, PEI, 1915–1925,” CCHA, Hist. Studies, 70 (2004): 29–47. Peter McGuigan, “Edmonton, Archbishop Henry O’Leary and the roaring twenties,” Alberta Hist. (Calgary), 44 (1996), no.4: 6–14. Sister Mary Electa [M. B. Murphy], The Sisters of Providence of St. Vincent de Paul (Montreal, 1961). Sister Mary Ida [M. J. Coady], “The birth and growth of the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Martha of Prince Edward Island” (ma thesis, Univ. of Ottawa, 1955). Sister Maura [Mary Power], The Sisters of Charity, Halifax (Toronto, 1956). Kenneth [J.] Munro, St. Joseph’s College, University of Alberta (Victoria, 2015). P. A. Nearing, “Rev. John R. MacDonald, St. Joseph’s College and the University of Alberta,” CCHA, Study Sessions, 42 (1975): 71–90. Art O’Shea, The O’Learys two (Charlottetown, 1995). E. F. Purcell, Priests of memory (Edmonton, 1991). Dahlia Reich and Sisters of St Joseph, Sister: the history of the Sisters of St. Joseph of London (London, Ont., 2007). Sheila Ross, “‘For God and Canada’: the early years of the Catholic Women’s League in Alberta,” CCHA, Hist. Studies, 62 (1996): 89–108. St. Joseph’s Auxiliary Hospital: 75th anniversary, 2002: a commemorative history (Edmonton, 2002). St Joseph Seminary, “Our history”: www.stjoseph-seminary.com/About/Our-History (consulted 26 July 2018). L. K. Shook, Catholic post-secondary education in English-speaking Canada: a history (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1971). Alphonse de Valk, “Catholic higher education and university affiliation in Alberta, 1906–1926,” CCHA, Study Sessions, 46 (1979): 23–47.

Cite This Article

Staff of the DCB/DBC, “O’LEARY, HENRY JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/o_leary_henry_joseph_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/o_leary_henry_joseph_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Staff of the DCB/DBC |

| Title of Article: | O’LEARY, HENRY JOSEPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2021 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |