Source: Link

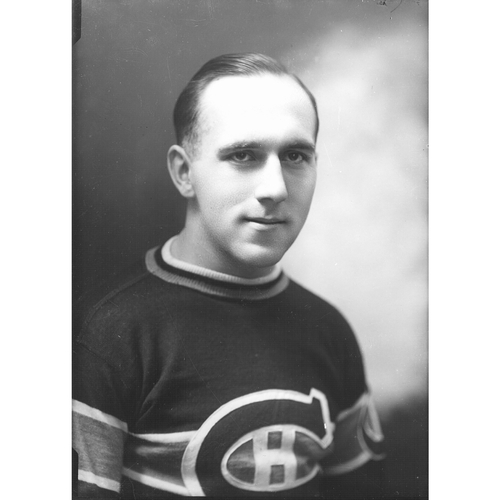

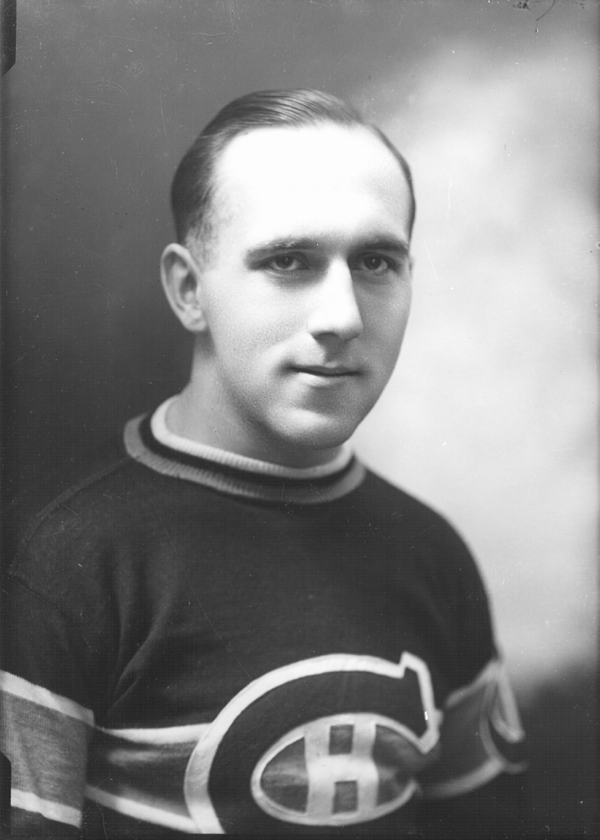

MORENZ, HOWARD WILLIAM (named at birth William F., also known by the nickname Howie), machinist, hockey player, and sales representative; b. 21 Sept. 1902 in Mitchell, Ont., son of William Frederick Morenz, a clerk, and Rose Pauli; m. 21 June 1926 Mary McKay in Montreal, and they had one daughter and two sons; d. there 8 March 1937.

The youngest in a family of six children, Howard Morenz attended the elementary public school near his home, in the town where he was born. He began playing hockey as a child, and from the age of ten he was beating his elder brother in skating races. He was developing at that time his fast, powerful stride, a skating style that would make him famous. A few years later, Howard’s father became an employee at the Grand Trunk Railway repair shops and moved his family to the neighbouring town of Stratford. To help them, Howard dropped out of school and worked in the shops as an apprentice machinist. From 1919 to 1922 he played for the Stratford Midgets of the Ontario Hockey Association Junior A league, where his performance was outstanding. During the 1921–22 season he scored a total of 23 points in four matches. That year Howie also played for both the Stratford Indians of the Ontario Hockey Association Senior A league and the local team of the Grand Trunk shops. Nicknamed “the Mitchell Meteor” and the “Stratford Streak,” he led all three teams to the championships.

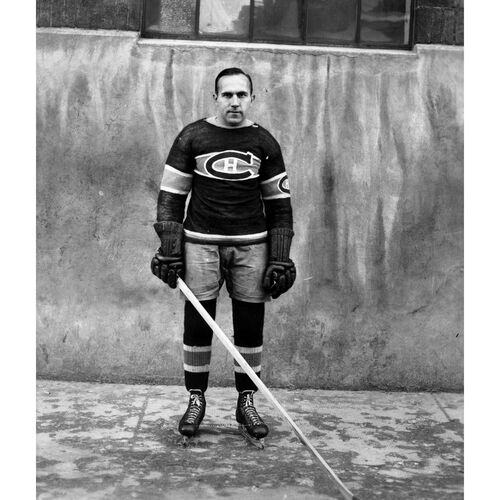

In 1923, during a game between the Montreal and Stratford teams of the Canadian National Railway Company (formerly the Grand Trunk), Morenz caught the attention of Léo Dandurand, the co-owner and coach of the National Hockey League’s Montreal Canadiens. Dandurand hired him, maintaining that the Canadiens had priority in the selection of French Canadian players and that, since his grandparents were of Swiss origin (that was a myth: they were actually of German extraction), Howie had to be considered a French Canadian. In this way Howie slipped through the fingers of the local team, the Toronto St Patricks. Dandurand offered him an annual contract at a salary of $2,500, plus a sum of $850 so that he could pay off his debts. Morenz was a spendthrift, a man of extremes in life as well as on the ice, and for this reason he accepted the offer of the Canadiens. His father signed the contract on 7 July 1923. But Morenz was suddenly stricken with remorse; he worried that playing for a professional team would affect his image and he was reluctant to leave his family. Unbending, Dandurand forced him to honour his contract. Morenz, who played centre, scored his first goal in the NHL on 6 Dec. 1923.

Like the majority of professional players of his time, Morenz had to work during the summer to supplement his income. He found a job at King’s Park Racetrack and later represented the Benson and Hedges tobacco company in advertising campaigns (he himself disliked cigarettes but smoked a pipe). Throughout his career he worked with charitable organizations as a member of the masonic order; he also helped his family and that of his wife in Stratford.

In the winter of 1924 the Canadiens won the Stanley Cup. Morenz, who was in his first year with the team, contributed to that victory by scoring seven goals in six games during the play-offs. He and Aurèle Joliat were the stars that season and became close friends. The Canadiens would not make it to the finals again until 1930, but that did not stop Morenz from being one of the highest scorers. He was ranked first in 1927–28 (33 goals, 51 points) and in 1930–31 (28 goals, 51 points). In 1928 he became the first player in the league to accumulate 50 points in a single season. He won the Hart Trophy – awarded to the player most valuable to his team during the regular season – in 1928, 1931, and 1932; he was the first to do so three times. In 1930 the Canadiens achieved success again by defeating the Boston Bruins in the finals. They held on to their title the following year when Morenz scored the winning goal against the Chicago Blackhawks (incorrectly written as two words, Black Hawks, until 1986).

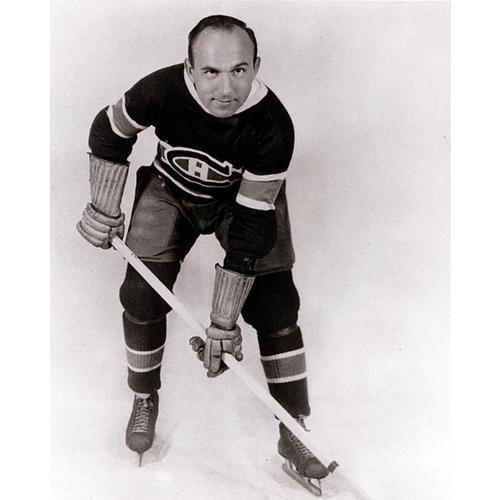

Morenz’s playing style attracted crowds. He threw opponents off balance by changing direction at the last moment. Body-checks did not stop him, and simultaneous collisions with two defencemen did not slow down his rush to the net. He mastered the deke, anticipated the play, and without question was the fastest player on the ice. He aroused so much interest that he contributed to the NHL’s expansion. Indeed, his prowess had convinced George Lewis (Tex) Rickard, a partner and friend of Dandurand’s, to add an ice rink to the new Madison Square Garden building in New York and to buy the Hamilton Tigers, who became the New York Americans. Rickard insisted that the Canadiens, and especially Morenz, take part in the opening game on 15 Dec. 1925. Because he was one of the dominant players in the league, he was called “the Babe Ruth of hockey” at that time.

After winning the cup in 1931, the Habs’ strength began to wane, as did that of Morenz, who was weakened by injuries and whose performance was so disappointing that the crowds sometimes booed him. Furthermore, Edward Cyril (Newsy) Lalonde*, the team’s new coach, did not get along with him. On 3 Oct. 1934 Morenz moved to the Chicago Blackhawks, where he had no greater success. They traded him to the New York Rangers on 26 Jan. 1936; he would score only two goals in 19 matches with that team before rejoining the Canadiens on 1 September. The return did him a world of good. He reconnected with the crowds and racked up 20 points in 30 games.

On 28 Jan. 1937, while playing against the Blackhawks at Montreal’s Forum, Morenz went after the puck in a corner of the rink and his skate got caught in the boards. Chicago defenceman Earl Seibert, who was unable to stop, body-checked him and fell on top of him. Morenz’s left leg was broken in several places. He underwent surgery and was kept at the Hôpital Saint‑Luc, where he had an endless stream of visitors. His season was over, and very likely his career as well.

Morenz, however, remained obsessed with hockey and winning. After a match he had sometimes spent the whole night going over his plays, blaming himself for a loss, and wondering what he could improve. In the hospital, where he was anxiously thinking about his return, he suffered a nervous breakdown. On 8 March 1937 his doctors, who had discovered blood clots in his leg, decided that they would operate the next day. But Morenz died of a heart attack at 11:30 that night, the clots having reached his heart. His body was placed on public view in the Forum, where nearly 200,000 people filed past his casket. About 15,000 people attended his funeral, which was held in the same place.

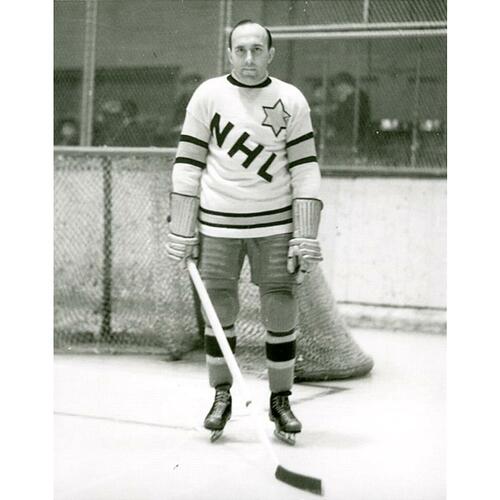

At the beginning of the following season, a group of businessmen and hockey personalities organized a fund-raising night in aid of the Morenz family. On 2 November the best players of the Montreal Canadiens and Montreal Maroons played against the best players of the other teams in the league. After the game, Howie’s sweater was auctioned for $500. Joseph Cattarinich, a former goalie and one-time owner of the Canadiens, purchased it and gave it to Howard Raymond, one of the sons of the deceased hockey player. The number 7, which Morenz had worn for 12 seasons, was retired forever that evening, a first in the NHL. In total, more than $20,000 was put in a trust, the interest from which would help secure the future of the Morenz family.

When the Hockey Hall of Fame was founded in 1945, Howard William Morenz was one of the first 12 players to be inducted. Despite the fact that he did not speak French, he was recognized as one of the great stars of the Canadiens and had had a role in the continuing popularity of the nickname “Flying Frenchmen,” which had been associated with the team for two decades. The successors to Jean-Baptiste (Jack) Laviolette, Didier Pitre, Georges Vézina*, and Newsy Lalonde, Morenz and his friend Aurèle Joliat were the last stars before the arrival of Maurice Richard*, known as the Rocket. By the end of his career, Morenz had scored 270 goals in 550 games. On ten occasions he was ranked among the top ten scorers of the NHL. His son Howard Raymond played at the senior level in Quebec and professionally in the United States. His daughter Marlene Mary married Bernard (Boom Boom) Geoffrion*. In 1979–80 their son Daniel (Danny) was with the Habs, as was their grandson Blake during the 2011–12 season, thus representing the fourth generation of his family to play for the team.

The author wishes to thank Howard Raymond Morenz and Howard G. Morenz for their valuable collaboration.

AO, RG 80-2-0-558, no.34010. BANQ-Q, E8, S8, 1926-112855. Le Devoir, 3, 27 nov. 1937. Gazette (Montreal), 9 March, 3 Nov. 1937. La Presse, 9 mars 1937. Pierre Bruneau et Léandre Normand, La glorieuse histoire des Canadiens (Montréal, 2003). Stan Fischler, Hockey’s 100: a personal ranking of the best players in hockey history (New York, 1984). Charles Mayer, L’épopée des Canadiens de Georges Vézina à Maurice Richard: 46 ans d’histoire, 1909–1955 (Montréal, 1956). Michael McKinley, Hockey: a people’s history (Toronto, 2006). Claude Mouton, The Montreal Canadiens: a hockey dynasty (Toronto, 1980); The Montreal Canadians: an illustrated history of a hockey dynasty (Toronto, 1987). Ont., Ministry of Culture and Recreation, Heritage administration branch, Historical sketches of Ontario ([Toronto], 1975), 32–34. Maurice Richard and Stan Fischler, The flying Frenchmen, hockey’s greatest dynasty (New York, 1971). Dean Robinson, Howie Morenz: hockey’s first superstar (Erin, Ont., 1982). Total hockey: the official encyclopedia of the National Hockey League, ed. Dan Diamond et al. (New York, 1998).

Cite This Article

Michel Vigneault, “MORENZ, HOWARD WILLIAM (William F., Howie),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/morenz_howard_william_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/morenz_howard_william_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michel Vigneault |

| Title of Article: | MORENZ, HOWARD WILLIAM (William F., Howie) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2015 |

| Year of revision: | 2015 |

| Access Date: | December 29, 2025 |