Source: Link

MARRANT, JOHN, freeborn Black American, author, and minister of the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion; b. 15 June 1755 in New York; m. 15 Aug. 1788 Elizabeth Herries at Birchtown, N.S.; d. 15 April 1791 in Islington (London), England.

John Marrant’s early life was exceptional in that he was able to obtain an education despite the severe restrictions placed on Black people in colonial America. He attended school until the age of 10 or 11, first in St Augustine, Florida, where his mother had moved on the death of her husband in 1759, and then in Georgia. When the family later settled in Charleston, South Carolina, it was intended that Marrant learn a trade. Instead, at his own wish, he studied music for two years before being apprenticed for over a year to a carpenter. At the age of 13 he experienced a spiritual rebirth at a revivalist meeting led by George Whitefield, the evangelical preacher of the Great Awakening [see Henry Alline]. Finding his family unsympathetic, he abandoned his home for the wilderness beyond Charleston. There he was found by an Indigenous hunter and taken among the Cherokee, with whom he lived for two years before returning to his family in Charleston.

At the outbreak of the American revolution Marrant was impressed into the Royal Navy as a musician and saw action in 1780 at the siege of Charleston and in 1781 off the Dogger Bank, in the North Sea, where he was wounded. After his discharge he worked for three years with a London cotton merchant and joined an evangelical group known as the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion, named for Selina Hastings, an aristocratic sponsor of the Methodist cause. A letter from his brother, one of the 3,500 Black loyalists transported to Nova Scotia after the revolution, described their yearning for Christian knowledge, and Marrant determined to become a missionary. He was ordained a minister in the Connexion on 15 May 1785 at Bath.

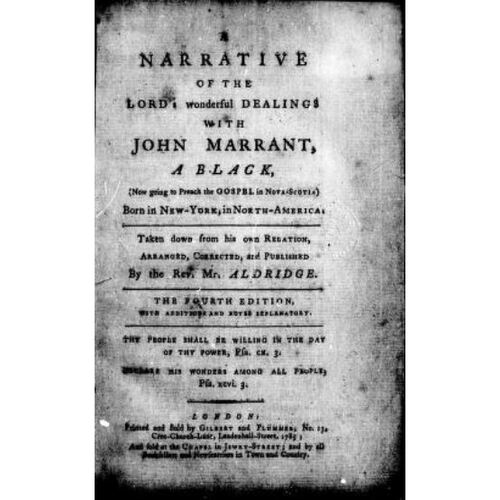

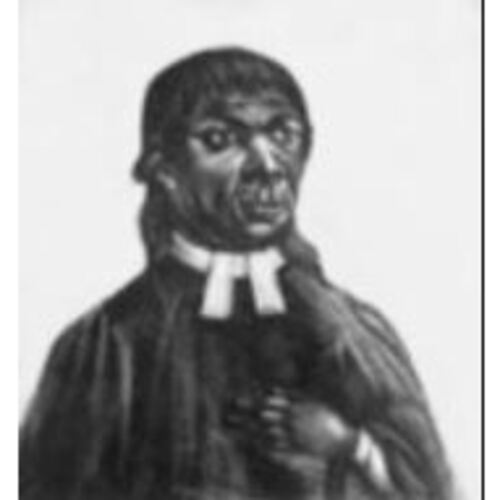

Marrant’s education and conversion combined to produce the two achievements for which he is remembered: the publication in London in 1785 of his account of the first 30 years of his life, and his Christian ministry among the Black loyalists of Nova Scotia. Between 1785 and 1835 A narrative of the Lord’s wonderful dealings with John Marrant, a black . . . appeared in at least 21 different printings, including one in Welsh. Its amazing success can be attributed to the fact that it made important contributions to three literary genres: the American slave narrative, the Indian captivity tale, and the evangelical Christian conversion record. Although Marrant was never a slave, his Narrative is numbered among the most influential of early Black writings because the pattern of his life paralleled the classic slave pattern of suffering and oppression, eventual escape, and journey to the promised land. After his death publishers, perhaps wishing to avoid the abolition controversy and stress the story of a Christian’s progress, omitted the reference to his colour in the title and even lightened his frontispiece portrait to obliterate his racial characteristics. These amended versions depended for their appeal on Marrant’s account of his residence among the Cherokee; his is considered to be one of the three most popular Indian captivity stories ever published.

Marrant himself seems to have regarded his Narrative as significant chiefly for its Christian message. It is tantalizingly silent on the details of his secular life, portraying instead a series of spiritual tests and victories often embodied in symbolic incidents that are hardly credible to modern readers. His conversion and subsequent adventures are all marked by miraculous escapes and prayers answered spontaneously. Marrant clearly saw himself as a living sermon. His struggle as a Black Christian in an irreligious, white, slave-owning world that made little distinction between slaves and freeborn Blacks was intended to inspire all readers, not only Blacks.

In Nova Scotia Marrant’s preaching contributed to a movement that had its parallel in the impact of his published Narrative. Although Black loyalists lived in poverty and oppression, they were able to create a vibrant culture centred on their Christian chapels and thus to endure as a distinct community. Marrant organized his first congregation at Birchtown, near Shelburne, and then embarked on a tour that took him to most Black loyalist settlements. Occasionally he preached to white congregations and visited Micmac (Mi’kmaq) villages. He was an effective preacher: several white ministers condemned him when their Black congregants deserted them for Marrant’s message and the all-Black chapels he established. Therefore, one important legacy of his ministry – and of the ministries of the Baptist preacher David George* and the Methodists Moses Wilkinson, John Ball, and Boston King* – was the creation of exclusively Black religious groups dedicated to the preservation of a unique Christian experience.

In 1787 Marrant travelled to Boston, where he joined the first Black Masonic lodge, founded in 1784 by Prince Hall, an American abolitionist. He became chaplain to the lodge, and several of his Boston sermons were published in both England and America. He did not, however, lose contact with his Nova Scotian flock, for he returned to the province to marry Black loyalist Elizabeth Herries at Birchtown on 15 Aug. 1788. In 1789, apparently believing his mission had been accomplished, he left for England. He continued his ministry at the main Huntingdonian chapel in Islington and on his death was buried in the adjoining churchyard.

John Marrant’s brief career is less important for its accomplishments than for its influence upon historical and literary trends among Black people in North America and in Africa. His was a message of perseverance, a testimony to the success a Black man who was a Christian could achieve through faith in God and in himself, and his Narrative served as a model for generations of Black American writers. Marrant’s followers became preachers and teachers in the Nova Scotian Black community, and with the migration of some 1,200 Black loyalists to Sierra Leone in 1792 [see Thomas Peters], his message was spread to thousands of Africans. His work survives in the descendants of his Black congregations.

The following works by John Marrant have been published: A journal of the Rev. John Marrant, from August the 18th, 1785, to the 16th of March, 1790 . . . (London, 1790); A narrative of the Lord’s wonderful dealings with John Marrant, a black . . . , ed. Rev. Mr Aldridge (London, 1785); and A sermon preached the 24th day of June, 1789 . . . (Boston, n.d.).

BL, Add. mss 41262A, 41262B, 41263, 41264. PANS, MG 1, 479 (Charles Inglis docs.), no.1 (transcripts). [John Clarkson], Clarkson’s mission to America, 1791–1792, ed. and intro. C. B. Fergusson (Halifax, 1971). [David George], “An account of the life of Mr. David George . . . ,” Baptist Annual Register (London), I (1790–93), 473–84. Great slave narratives, comp. A. [W.] Bontemps (Boston, 1969). Held captive by Indians: selected narratives, 1642–1836, comp. Richard VanDerBeets (Knoxville, Tenn., 1973). [Boston King], “Memoirs of the life of Boston King, a black preacher . . . ,” Methodist Magazine (London), XXI (1798), 105–10, 157–161, 209–13, 261–65. C. [H.] Fyfe, A history of Sierra Leone (London, 1962). J. W. St G. Walker, The black loyalists: the search for a promised land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone, 1783–1870 (London, 1976); “The establishment of a free black community in Nova Scotia, 1783–1840,” The African Diaspora: interpretive essays, ed. M. L. Kilson and R. I. Rotberg (Cambridge, Mass., and London, 1976). R. W. Winks, The blacks in Canada: a history (Montreal, 1971). C. [H] Fyfe, “The Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion in nineteenth century Sierra Leone,” Sierra Leone Bull. of Religion (Freetown, Sierra Leone), 4 (1962), 53–61. D. B. Porter, “Early American Negro writings: a bibliographical study,” Bibliographical Soc. of America, Papers (New York), 39 (1945), 192–268. A. F. Walls, “The Nova Scotian settlers and their religion,” Sierre Leone Bull. of Religion, 1 (1959), 19–31.

Cite This Article

James W. St G. Walker, “MARRANT, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/marrant_john_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/marrant_john_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | James W. St G. Walker |

| Title of Article: | MARRANT, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1979 |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |