Source: Link

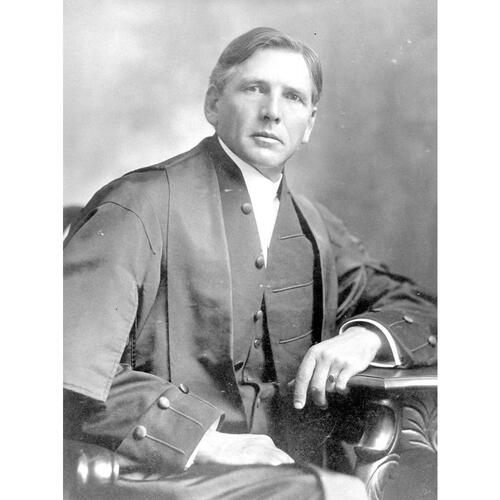

MACDONALD, JAMES ALEXANDER (he sometimes spelled his name McDonald), lawyer, politician, and judge; b. 1858, probably in Tuckersmith Township, Upper Canada, son of James Macdonald and Isabella Rodger; m. 31 July 1890 Mary Richardson in Stratford, Ont., and they had two daughters and a son; d. 20 Dec. 1939 in Victoria.

James Alexander Macdonald grew up in Huron County and moved with his family to Stratford, in neighbouring Perth County, where in 1876 his father established the MacDonald and MacPherson Company, maker of the famous Decker Threshing Machine. His two brothers would join their father in managing the company. James also worked at the foundry, casting metals, from age 20 to 25, when he chose to pursue higher education.

Macdonald studied at Stratford Central Secondary School and the Stratford Collegiate Institute. Starting in 1883 he attended the University of Toronto and then Osgoode Hall law school. He did legal work in Stratford with John Idington* from 1884. Called to the bar around 1890, he practised in Toronto with the firm of Fullerton, Cook, Wallace, and Macdonald until 1896. That year he moved to the booming mining town of Rossland, B.C., which would reach a population of some 7,000 in 1897. One of about 50 lawyers who had relocated to the burgeoning city to make their fortunes, he would work with various partners (and briefly on his own in 1903) until 1909 as a barrister, solicitor, and notary public.

Macdonald was admitted to the provincial bar on 3 May 1897, appointed kc in 1905, and elected a bencher of the Law Society of British Columbia in 1907. He practised first with former mayor John Stilwell Clute and became a solicitor and legal counsel for the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company of Canada (also known as Cominco), the Granby Consolidated Mining, Smelting and Power Company, and other large firms. He attracted attention for his handling of many bankruptcies and was among the best in his profession in the region. He lived on Union Avenue with his wife and three children, and owned four other properties. An active curler, he helped fund the construction of the local rink in 1908 and was an honorary president of the Rossland Skating and Curling Rink Limited.

Thanks in part to his business background, Macdonald was a member of the British Columbia Mining Association from 1903 to 1909 and served as its first president. Active in the provincial Liberal Party and at one time president of the Kootenay Liberal Association, he was elected mla for Rossland City’s first seat in 1903 – defeating the provincial cabinet secretary. That same year former premier (February–June 1900) Joseph Martin*, a brusque and headstrong politician, resigned as Liberal leader, and Macdonald was chosen to succeed him. Macdonald had taken a position against Martin’s labour legislation, which was particularly unpopular in Rossland and region. He would be re-elected its mla in 1907 after having made a bitter attack on the Canadian Pacific Railway. Tall, thin, and, as historian Margaret Anchoretta Ormsby describes him, “with the face like that of a refined Indian chief,” he was a keen and vigorous debater, but lacked charisma.

As leader of the opposition, Macdonald at first supported the Conservative government of Richard McBride* in its mission to obtain “better terms” from confederation, which involved asking the dominion to reduce the province’s debts in light of the costs of administering such a large and mountainous region, and on 24 Feb. 1905 Macdonald seconded a resolution to this effect. The British North America Act would be amended in August 1907 as a result. He also worked with the government to restrict immigration from southern and eastern Asia; in the campaign for the election on 2 Feb. of that year, he had taken a particularly hard line against “undesirable immigrants.” Despite giving his support on these two matters, Macdonald fought the McBride government fiercely on issues of corruption. In 1906, after learning that the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway had been granted a bonus of 10,000 acres on Kaien Island for its port terminus, he requested that a select committee of the legislature be formed to investigate. The committee’s minority report stated that the government had known it was dealing with speculators, rejected other applications on false grounds, and lacked the authority to make the grant without the legislature’s approval. But the majority report exonerated the government, claiming that the grant was in the best interest of the province and no government members or officials had personally benefited from it.

Meanwhile, Macdonald was not immune to suspicion himself: according to the Daily Colonist (Victoria), members of his riding association, as well as his opponents, were reported to have distributed liquor, cigars, and money to constituents in the run-up to the provincial election of 1907. Macdonald continued to try to expose corruption in the Conservative government and was very successful in opposition. A proponent of the British concept of non-partisan government, he was known as a cool-headed man of integrity, a supporter of miners and entrepreneurs with a positive view of all classes, and a keen promoter of natural resources. He argued for what he termed “equal” taxes, better wages for workers, a more efficient civil service, and a balanced budget.

Macdonald accepted an appointment by the federal Liberal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier* as chief justice of the newly created British Columbia Court of Appeal on 30 Nov. 1909, having resigned from his political office on 23 October with advance knowledge of his nomination. On that day he had given a speech for the party in Trail, caught the train home in the evening, and, to save himself a long walk, had it stop on a steep embankment near his house. Jumping off, he hit his head and was badly bruised.

The Court of Appeal Act, 1907, had been sponsored by the British Columbia Law Society, which for years attempted to convince the provincial government of the need for an entity, separate from the Supreme Court, to hear appeals. The establishment of the Court of Appeal, which first sat on 4 Jan. 1910, was modelled on the recent Manitoba Court of Appeal and was not without conflict. Politically, McBride’s Conservative government was not happy that the Liberal Macdonald had been named a chief justice; however, the federal Liberal government was quite pleased with its choice. Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier, like his predecessor Sir John A. Macdonald*, nearly always appointed party members. Moreover, the chief justice of the provincial Supreme Court, Gordon Hunter, was considered by many to be ill suited to hear appeals: his alcoholism had become public knowledge, and his image had been marred by newspaper reports recounting his “strange behaviour” and by editorials urging him to resign. But Hunter, holding the title of chief justice of British Columbia, remained in office for another 20 years, spending most of his time vacationing at his estate on Shawnigan Lake. After Hunter’s death in 1929 Macdonald became the province’s chief justice, with rank and precedence over the judges of the Supreme Court.

One of Macdonald’s major tasks as chief justice of the Court of Appeal was to contain the public damage caused by one of his associates, the brilliant and eccentric Archer Evans Stringer Martin*. Martin built his judicial career on mercilessly denouncing legal errors made in lower courts, including the provincial Supreme Court. On numerous occasions Macdonald had to temper his associate’s words to maintain a working relationship with Supreme Court judges. Macdonald’s understanding of government procedure served him well in World War I, when he filled in for Lieutenant Governor Frank Stillman Barnard in October 1915 and in January and February 1917.

A judicial conservative, Macdonald was not a progressive or innovative judge. His goals, which were revealed in his decisions, were to react positively to business demands for legal certainty, defend the freedom of contract and property rights in a market economy, and strongly uphold the public peace. A strict constructionist when it came to interpreting the law, he applied legislation exactly as it had been written. A case in point was the historic appeal of Mabel Priscilla Penery French* against the provincial law society’s refusal to accept applications from women. After the society rejected such applications in 1908 and 1910, French, a barrister from New Brunswick, applied to the Supreme Court of British Columbia for a writ of mandamus to compel the society to accept her application. When the court refused, she appealed. Macdonald was sympathetic in his judgement, recognizing that society already accepted women in professions such as the law. He reasoned on 9 Jan. 1912, however, that since England did not allow women to practise, neither should British Columbia. The change would have to come from the legislature – and the Conservative government introduced a bill to this effect the following month.

James Alexander Macdonald retired from the court in 1936 and died three years later after a long illness. His entire estate was valued at $13,743.37. Survived by his wife, a son (a civil servant), and a daughter, he left no debts. Inheriting his father’s quiet disposition and habit of paying attention to detail, he was, despite his Liberal label, as conservative in his personal finances as he was in politics and the law.

Ancestry.com, “British Columbia, Canada, death index, 1872–1990”; “Ontario, Canada, marriages, 1801–1928”: www.ancestry.ca (consulted 10 Feb. 2015). BCA, GR-1304; MS-2369. Rossland Museum and Discovery Centre Arch. (Rossland, B.C.), Rossland tax rolls, 1898–1909. Rossland Miner, 1899–1910. Stratford Daily Beacon (Stratford, Ont.), 12 Dec. 1911. Stratford Herald, December 1898, special edition entitled Souvenir Trade Edition. Trail Creek News (Trail, B.C.), 1904. Trail Daily Times, 1939. Trail News, 1904–9. Vancouver Daily Province, 21 Dec. 1939. F.‑J. Audet, Dictionnaire biographique des gouverneurs, lieutenants-gouverneurs et administrateurs du Canada et de ses provinces, 1604–1921 (2v., s.l., n.d.). Joan Brockman, “Exclusionary tactics: the history of women and visible minorities in the legal profession in British Columbia,” in Essays in the history of Canadian law, ed. D. H. Flaherty et al. (10v. to date, [Toronto], 1981– ), 6 (British Columbia and the Yukon, ed. Hamar Foster and John McLaren, 1995), 508–62. Canada and its provinces: a history of the Canadian people and their institutions …, ed. Adam Shortt and A. G. Doughty (23v., Toronto, 1913–17). Canadian who’s who, 1910, 1936–37. The Canadian who’s who with which is incorporated “Canadian men and women of the time” … (Toronto, 1972). Directory, B.C., 1897–1914. Directory, Toronto, 1890–94. Encyclopedia Canadiana, ed. J. E. Robbins (10v., Ottawa, 1957–58). Hamar Foster and John McLaren, “For the better administration of justice: the Court of Appeal for British Columbia, 1910–1920,” BC Studies (Vancouver), no.162 (summer 2009): 47–62. Philip Girard, “Politics, promotion, and professionalism: Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s judicial appointments,” in Essays in the history of Canadian law, ed. D. H. Flaherty et al. (10v. to date, [Toronto], 1981– ), 10 (A tribute to Peter N. Oliver, ed. Jim Phillips et al., 2008), 169–99. Christopher Moore, The British Columbia Court of Appeal: the first hundred years (Vancouver, 2014). M. A. Ormsby, British Columbia: a history ([Toronto], 1958). P. E. Roy, Boundless optimism: Richard McBride’s British Columbia (Vancouver, 2012); A white man’s province: British Columbia politicians and Chinese and Japanese immigrants, 1858–1914 (Vancouver, 1989). D. R. Verchere, A progression of judges: a history of the Supreme Court of British Columbia (Vancouver, 1988).

Cite This Article

Louis A. Knafla, “MACDONALD (McDonald), JAMES ALEXANDER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_james_alexander_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_james_alexander_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Louis A. Knafla |

| Title of Article: | MACDONALD (McDonald), JAMES ALEXANDER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2020 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | December 18, 2025 |