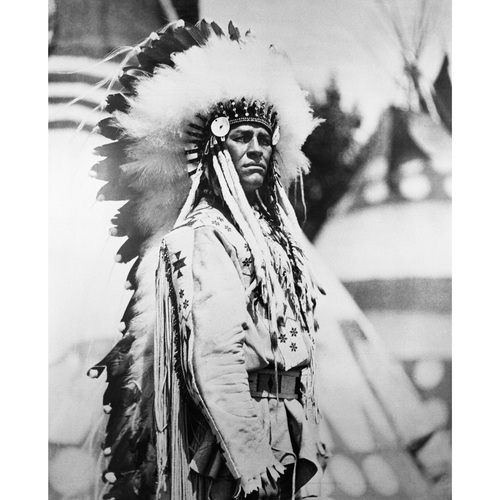

![Long Lance, Indian author and newspaperman [ca. 1920s]. Photographer/Illustrator: McDermid Studio, Calgary, Alberta. Image courtesy of Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta. Original title: Long Lance, Indian author and newspaperman [ca. 1920s]. Photographer/Illustrator: McDermid Studio, Calgary, Alberta. Image courtesy of Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta.](/bioimages/w600.11405.jpg)

Source: Link

LONG, Sylvester Clark, known as Sylvester Chahuska Long Lance, Buffalo Child, and Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance, soldier, journalist, lecturer, author, and actor; b. 1 Dec. 1890 in Winston (Winston-Salem), N.C., son of Joseph Sylvester Long and Sallie Malinda Carson; d. unmarried 20 March 1932 in Arcadia, Calif.

Sylvester C. Long’s parents had both been born slaves. Joe Long thought that his father was white and his mother Eastern Cherokee. Sallie Carson had been told that her ancestry was also aboriginal (Croatan, now known as Lumbee) and European. Regardless of what Joe and Sallie believed, they were not federally recognized Indians and consequently had no legal status as Native Americans. Even had it been otherwise, in Winston there were only two racial classifications, white and coloured, and as non-whites the Longs lived in the African American community and suffered much of the discrimination faced by their black neighbours.

In 1897 Sylvester learned the full implications of being labelled coloured. Although his father worked as a janitor at an elementary school only three blocks from their home, the six-year-old could not enrol there since the institution was for white children. He must attend the Depot Street School for Negroes two miles away. The colour line in Winston was indelibly drawn, and he would come to resent the daily humiliations it imposed.

From an early age Long fantasized about Indians. As a boy of 13 and again when he was 17 or 18 he joined wild west shows, where, with his straight jet-black hair, high cheekbones, and copper skin, he was taken to be a Native American. In 1909, falsifying the extent of his Indian ancestry and capitalizing on his appearance and the fact that he had learned some Cherokee while on the road, Long applied to and was accepted by the famous Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pa.

At this federally supported institution, whose student body included members of nearly 100 aboriginal groups from across the United States and whose football team brought it nationwide attention, Long excelled both in his studies and in sports. The school completely altered his life. There he put himself forward as an Eastern Cherokee. This portrayal was not entirely a distortion, given his father’s presumed ancestry. Moreover, at the time a number of Croatan, the people from whom his mother claimed descent, were presenting themselves as Eastern Cherokee, a group that had, unlike the Croatan, received federal recognition. The school also opened up new opportunities. Having achieved a fine record there, Long gained entrance in 1912 to Conway Hall in Carlisle, the preparatory school for Dickinson College. After a year he won a scholarship to St John’s Military Academy in Manlius, N.Y., where he Indianized his name to Sylvester Chahuska Long Lance. He completed his high-school education in 1915, at age 24, and spent an additional year of study there. His time at school had not been free of suspicions about his origins, and such questions would continue to dog him.

Perhaps in search of adventure, or regular pay, Long Lance travelled north to Montreal in early 1916 and enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Eventually he saw four months’ action in France in 1917. Wounded twice, he was hospitalized in England on the second occasion and subsequently assigned to non-combat duties. Upon his return to Canada in 1919, he boarded a troop train heading west and took his discharge in Calgary, far from the American South he was trying to escape. Introducing himself as a Cherokee from Oklahoma, that is, a Western Cherokee, the first major distortion of his identity, he obtained a job as a reporter for the Calgary Daily Herald.

During his three years with the paper Long Lance made frequent visits to reserves in southern Alberta. The accomplished war veteran was adopted by the Blood, one of the four nations in the Blackfoot Confederacy, as an honorary chief in February 1922 and given the name Buffalo Child. When he left for Vancouver two months later, having been fired from the Herald because of a reckless practical joke, he took with him his new name and his new Plains Indian identity. If asked, he described himself usually as a Blackfoot, sometimes as a Blood. He was not, of course, in any way a legal member of either group.

In the early and mid 1920s, now calling himself Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance, the talented writer penned articles, based on personal investigations, about aboriginal people in British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. Major North American newspapers and magazines bought these pieces, in which he aired a positive interpretation of the history of the First Nations in Canada and reviewed their contemporary situation. In 1927, having travelled widely in the west and elsewhere pursuing stories, covering boxing matches, and giving lectures, he moved to New York City, where, a year later, he published Long Lance, a work he intended as a piece of historical fiction but one his publisher insisted should appear as autobiography. The critics generally praised it. Writing in the New York Herald-Tribune on 14 Oct. 1928, Paul Radin, a well-known American anthropologist, described it as “authentic” and an “unusually faithful account of childhood and early manhood.… I cannot think of any work that could act as a better corrective of the ridiculous notions still prevailing about the Indians.” At this point Sylvester Long’s reinvention of his identity became complete.

Long Lance’s “autobiography” brought wide public recognition, entry into New York’s highest literary and social circles, and an invitation to take a leading role in a film, The silent enemy, about the life of the Ojibwa in northern central Canada before the arrival of the Europeans (the “silent enemy” was hunger). Upon its release in 1930 Variety (New York) praised his performance in its issue of 21 May: “Chief Long Lance is an ideal picture Indian, because he is a full-blooded one … an author of note in Indian lore, and now an actor in fact.”

Yet, at the height of his fame, Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance’s stature as a public figure began to decline. Notoriety had aroused curiosity, and it was increasingly difficult to avoid investigations into his origins. Rumours began to circulate in New York that he was African American. Although he had continued to send money home to Winston-Salem, a reappearance there would mean certain discovery and he was unwilling in any case to live again in the ghetto. The strain of imminent exposure started to tell on him, and he turned to alcohol. In 1931 he moved to California, to act as secretary and bodyguard to a wealthy heiress embarking on a trip to Europe. Something happened during this journey to unsettle him further; he suffered bouts of depression and continued to drink heavily. After his return in November he became increasingly unstable, and on 20 March 1932 he took his own life, by gunshot, at his patron’s home in Arcadia, near Los Angeles.

Long’s legacy is his writings on the First Nations, in which he did good work in combating many negative stereotypes of aboriginal people. For these articles he carried out, as historian Hugh A. Dempsey has noted, “valuable field work at a time when few ethnologists, and even fewer journalists, were concerned about the history of the Indian.”

This article is based on the author’s full-length biography of Sylvester Clark Long, Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance: the glorious imposter (rev. ed., Red Deer, Alta, 1999). The GA holds the most complete collection of writings by and about Long (M 690, M 6240, M 6348, M 6426, NA 1811 (1–22), NA 3264, NA 3771, NB 25, PA 1086, PB 310, PE 38, S 28). Long’s “autobiography,” Long Lance, first appeared in New York in 1928. The latest edition is that published in 1995 by the University Press of Mississippi in Jackson. Roberta Forsberg compiled Redman echoes: comprising the writings of Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance, and biographical sketches by his friends (Los Angeles, 1933). This book also appears in the National Library of Can., Peel bibliography on microfiche ([Ottawa], 1975– ), no.3328.

Cite This Article

Donald B. Smith, “LONG, SYLVESTER CLARK (Sylvester Chahuska Long Lance, Buffalo Child, Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/long_sylvester_clark_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/long_sylvester_clark_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Donald B. Smith |

| Title of Article: | LONG, SYLVESTER CLARK (Sylvester Chahuska Long Lance, Buffalo Child, Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2016 |

| Year of revision: | 2016 |

| Access Date: | December 28, 2025 |