Source: Link

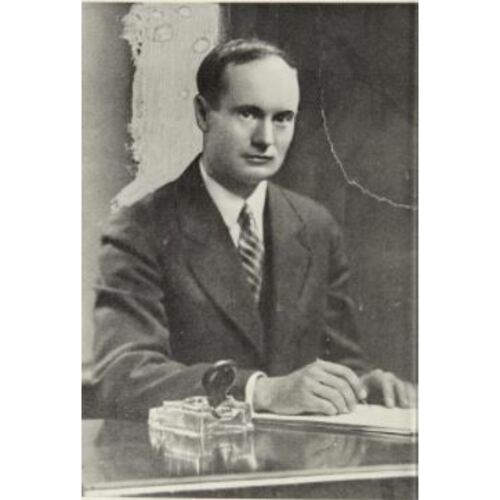

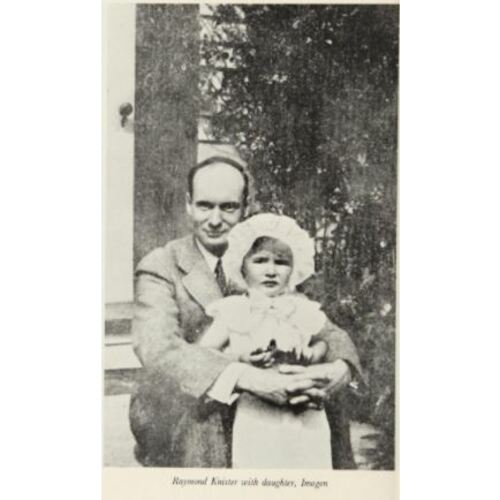

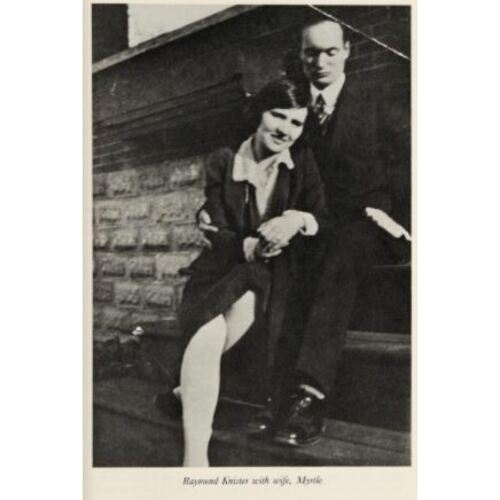

KNISTER, JOHN RAYMOND, author, editor, and journalist; b. 27 May 1899 in Rochester Township (Lakeshore), Ont., son of Robert Walter Knister and Elizabeth (Liza) Banks; m. 8 June 1927 Myrtle Maggie Bessie Gamble in Toronto, and they had a daughter; d. 29 Aug. 1932 at Stony (Stoney) Point, Ont.

John Raymond Knister, one of the most important figures in Canadian literature in the early 20th century, was of German stock, his paternal great-grandfather having immigrated from Germany to Essex County, Upper Canada, after the Napoleonic Wars. His father was a prominent farmer in Essex and Kent counties, growing corn and soybeans and importing Clydesdale horses from Scotland; his mother was a teacher; and one of his relatives was Dr Charles Knister, whose fine home – one of the first in the area with telephone service, to accommodate his medical practice – still stands.

Young Raymond (he went by his middle name only) therefore grew up in a farming environment and yet also had exposure to a world of sophistication and elegance. Afflicted with a stutter that would remain with him throughout his life, he was a shy boy who, when not busy with farm chores, read voraciously, poring over more than a thousand books between the ages of 15 and 25. In 1919 he entered Victoria College at the University of Toronto; while there he published essays on Cervantes and Robert Louis Stevenson in Acta Victoriana (Toronto), and wrote stories and poems about rural life that appeared in farming periodicals. One of his teachers at Victoria was Oscar Pelham Edgar*, who was to remain a supporter of his literary endeavours in the years ahead. Raymond’s scholastic career ended in 1920, however, when he contracted pneumonia (which may have resulted from a bout of Spanish influenza). After recovering at home, he worked on the family farm and continued writing poetry, short stories, and magazine articles, as well as book reviews for the Detroit Free Press and the Windsor Border Cities Star. Most of these writings drew on his farm experiences. In 1923 he moved to Iowa City, where besides taking university courses, he became an associate editor of the Midland, a literary magazine of some importance, founded by the well-known critic H. L. Mencken. It had already published several of Knister’s poems. The next year, still struggling to become a full-time writer, he moved to Chicago. There he wrote by day and drove a cab by night, contributing review articles to Poetry magazine and the local Evening Post. His experiences in a city then known for its criminal underworld were the basis of his story “Innocent man,” in which a cab driver is arrested and spends a night in jail with the gangsters who had taken over his car. In 1925 Knister was made a correspondent for the journal This Quarter (published mainly in Paris), whose writers included many major literary figures, among them James Joyce, Carl Sandburg, and Ernest Hemingway.

In 1926 Knister became engaged to Marion Mckenzie Font, whom he had met at the University of Iowa; however, the relationship broke down over religious objections from both his and her parents – the former were Protestants, the latter Catholics – and over Marion’s insistence that he give up writing for a more lucrative occupation. Later that year, on moving to Toronto, he met Myrtle Gamble, a dressmaker and former student at the Ontario College of Art (one of her teachers had been Arthur Lismer*); they married in the spring of 1927. Myrtle reportedly found Raymond’s “habit of quoting poetry” and his “outrageous sense of humour” charming, and she provided steadfast support of his career as a writer.

His return to Toronto was a crossroads in another way. There he became part of a literary circle that included writers such as Morley Edward Callaghan*, Mazo de la Roche*, Merrill Denison*, and Charles George Douglas Roberts*, and he published short stories in the Toronto Star Weekly and William Arthur Deacon*’s Saturday Night; the Star Weekly stories were set in the fictional community of Corncob Corners. Ryerson Press of Toronto accepted for publication his Windfalls for cider, a collection of nature poems, though the book did not appear until 1983, long after his death. Before the end of the decade, Knister had edited an anthology, Canadian short stories (1928), and published his first novel, White narcissus (1929), works that greatly enhanced his position in Canadian literature.

In 1929 the Knisters moved to a farmhouse near Port Dover, and it was there that Raymond completed My star predominant, a fictional treatment of John Keats’s last years, which would win first prize in a literary competition but would, like his nature poems, be published posthumously; because of the sponsoring publisher’s financial difficulties, Raymond was to receive only part of the prize money. Two years later he relocated once more, this time to Montreal, with Myrtle and their one-year-old daughter, Imogen. There he became part of a group of modernist writers that in time would include Dorothy Livesay*, Frederick Philip Grove*, John Leo Kennedy*, Abraham Moses Klein*, and Francis Reginald Scott*. Lorne Albert Pierce* of Ryerson Press offered Knister a job as editor in 1932, but it was not to be. In August, while staying at a family cottage in Ontario, he drowned in Lake St Clair at Stony Point. His body was not found for three days, despite an intensive search conducted by divers, boats, and a plane. Reacting to the news, Pierce said that Knister’s untimely death “meant the loss of a magnificent spirit, the promise of a kindling force in Canadian letters.”

Knister’s early and sudden death led some of his contemporaries to hint at suicide. Morley Callaghan, for example, noted that his tragic end spoke to the struggles of Canadian writers to make a living from their craft, struggles that became all the greater with the onset of the Great Depression. In 1949, 17 years after Knister’s passing, the suggestion of suicide gained fresh currency when Dorothy Livesay strongly intimated in a memoir appended to a collection of his poetry that depression had led him to take his own life. The claim elicited robust denials both from his daughter and from Leo Kennedy. Imogen drew on the testimony of her mother, who in a diary entry written just after Raymond’s death, related what he had said to her: “I feel just like Keats did when he was just coming into his powers. I feel as though I am just coming into mine. The world is before us, Myrtle. We have everything we want and we are happy.” Kennedy, for his part, had heard the talk of suicide soon after Knister’s death, and he would have none of it. Four years before Livesay published her account, he wrote to her in the bluntest terms, likely in an effort to dissuade her from printing her suspicions:

If anyone was close to Raymond Knister in his last year, I was, and I will swear on as high a stack of Bibles as you elect that the man drowned. What is more, I shall be happy to go into print and fight the first published inference that such wasn’t the case. I shall fight you, if you like. And I’ve a docket of evidence as long as your arm. When Raymond Knister drowned … he was on his way up.… Everything was going good for that guy and he knew it. He said it. He wrote it to me. These are some of the reasons I shall be most happy to knock the block off the first sensationalist who starts construing his tragic death as self-destruction.

Livesay published her account anyway, but the weight of evidence strongly favours the view that Knister’s death was accidental.

Whatever the circumstances of Knister’s death, there can be no uncertainty about his literary importance. In a brief career that spanned less than a decade, he was remarkably prolific, producing about 100 poems, roughly the same number of stories and sketches, four novels, dozens of essays, book reviews, and editorials, as well as the landmark anthology Canadian short stories. The sheer volume of publications is proof of Knister’s single-minded dedication. He never became wealthy through his writings, though he did manage to earn a respectable living – which was no small achievement in the 1920s and 1930s. His daughter would recount that her parents, with the income earned from her father’s writings and her mother’s dressmaking, lived modestly but well: “They had no debts and owned a good car, new furniture, good clothes, and a large collection of valuable books.”

Yet what marks out Knister as an important literary figure is not the quantity of his publications but their quality. Contemporary writers saw much to praise in his work. Morley Callaghan thought Knister’s poems on rural life “effortlessly authentic” – one “could smell the farm in them” – and described Canadian short stories as “a pillar of the times in Canadian writing.” Leo Kennedy believed that Knister was “genuinely a Canadian novelist in that he writes of the Canadian scene with understanding and feeling, not through pseudo-patriotic idealism, but because it is irrevocably a part of his conscious makeup. He does not exploit the Canadian background for mercenary purposes; he interprets it because he is of it; because his outlook on life is still largely that of the country boy behind the plough … he has retained a simplicity of judgment, a quality of unsophistication, to which is allied the factor of broad, inclusive observation.”

Later commentators have been just as generous. Anne Burke writes that Knister’s poetry “is exemplified by simple straightforward stanzas about modern life and aims at the starkness of absolute truth.” Colin Hill observes in the Literary encyclopedia: “Knister’s short fiction is remarkably varied in technique and is best seen as a series of eclectic and ambitious experiments with modern-realist form.… [His] best fiction … combines an almost Hemingwayesque treatment of reality with a Joycean interest in human psychology.” Hill concludes: “Raymond Knister’s reputation continues to grow as more and more of his works come to light, and critics increasingly recognize the pioneering role he played in the development of Canadian literature. He was among the first Canadian writers to advocate an international standard in Canadian writing, and to be aware of and noticed by foreign modernist circles. At the same time, he championed Canadian subjects and issues and wrote about his country with an uncompromising realism.”

A complete list of John Raymond Knister’s writings can be found in A[nne] Burke, “Raymond Knister: an annotated checklist,” Essays on Canadian Writing (Downsview [Toronto]), 16 (fall 1979–winter 1980): 20–61. Knister is the editor of the anthology Canadian short stories (Toronto, 1928). His principal publications include White narcissus (London, 1929; repr., afterword Morley Callaghan, Toronto, 1990), My star predominant (Toronto, [1934]), and three works published posthumously in Windsor, Ont.: Windfalls for cider … the poems of Raymond Knister, ed. Joy Kuropatwa (1983); There was a Mr. Cristi (2006); and Hackman’s night and taxi driver (Windsor, 2007). See also Collected poems of Raymond Knister, ed. and memoir Dorothy Livesay (Toronto, 1949); Selected stories of Raymond Knister, ed. and intro. Michael Gnarowski (Ottawa, 1972); and The first day of spring: stories and other prose, comp. and intro. Peter Stevens (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1976). The manuscript of Knister’s “Innocent man” (c. 1932) is preserved at the E. J. Pratt Library, Victoria Univ. in the Univ. of Toronto, Special collections, fonds 18.

AO, RG 80-05-0-1669, no.003334; RG 80-2-0-490, no.011756; RG 80-8-0-1396, no.040027. Victoria Univ. in the Univ. of Toronto, E. J. Pratt Library, “Raymond Knister: poet & writer”: library.vicu.utoronto.ca/collections/special_collections/f18_raymond_knister (consulted 3 June 2021). “Chronological history of Raymond Knister,” comp. Bonita O’Halloran, Journal of Canadian Fiction (Montreal), 4 (1975), no.2: 194–99. Encyclopedia of literature in Canada, ed. W. H. New (Toronto and Buffalo, 2002). Imogen Givens [Knister], “Raymond Knister – man or myth?,” Essays on Canadian Writing, 16: 5–19. Colin Hill, “Raymond Knister,” in The literary encyclopedia: www.litencyc.com (consulted 27 May 2021). Leo Kennedy, “Raymond Knister,” Canadian Forum (Toronto), 12 (1931–32): 459–61. The Oxford companion to Canadian history and literature, ed. Norah Story (Toronto, 1967). “Some annotated letters of A. J. M. Smith and Raymond Knister,” ed. and intro. Anne Burke, Canadian Poetry (London, Ont.), 11 (fall/winter 1982): 98–135. Marcus Waddington, “Raymond Knister: a biographical note,” Journal of Canadian Fiction, 4, no.2: 175–92.

Cite This Article

Micheline Maylor in collaboration with Curtis Fahey, “KNISTER, JOHN RAYMOND,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 25, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/knister_john_raymond_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/knister_john_raymond_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Micheline Maylor in collaboration with Curtis Fahey |

| Title of Article: | KNISTER, JOHN RAYMOND |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2022 |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | December 25, 2024 |