Source: Link

JACQUELIN, FRANÇOISE (Françoise-Marie), Acadian heroine, wife of Charles de Saint-Étienne de La Tour; baptized 18 July 1621 in Nogent-le-Rotrou, France, daughter of Jacques Jacquelin, medical doctor, and Hélène Lerminier; d. 1645 at Fort La Tour (also called Fort Sainte-Marie).

Little is known about Françoise Jacquelin’s life before 31 Dec. 1639, the day in Paris she signed a marriage contract with Charles de La Tour in the presence of his La Rochelle agent, Guillaume Desjardins Du Val. She sailed for Port Royal (Annapolis Royal, N.S.), where the ceremony was performed the following year. The couple settled at La Tour’s fort, situated at the mouth of the Saint John River. Here she made her home and gave birth to a son.

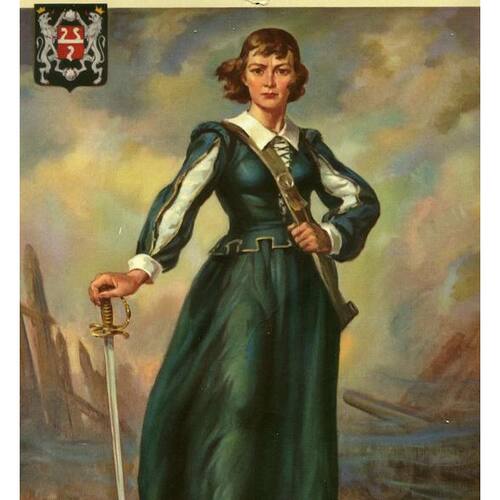

Almost immediately after her marriage, she became her husband’s courageous supporter in a struggle with Charles de Menou d’Aulnay for power in Acadia. In 1642 she evaded d’Aulnay’s blockade of the Saint John River and made her way to France, where she successfully appealed against the king’s order that her husband be arrested and brought to France on charges of disloyalty. She was given permission to take back a warship with supplies for Fort La Tour at Saint John harbour. Two years later, she again sailed for France, this time to find La Tour completely discredited at court owing to charges brought by d’Aulnay. Despite the fact that she herself was forbidden to leave France, Mme de La Tour borrowed money from friends and escaped to England, where she bought supplies and chartered a ship to carry her to the Saint John River. The trip lasted six months, the ship’s commander, Capt. Bailey, having stopped on the Grand Banks to fish. Off Cap de Sable, the vessel was stopped by d’Aulnay but Mme de La Tour hid in the hold and escaped detection. When the vessel landed in Boston, she sued the captain both for unnecessary delay and for not taking her to the Saint John River as he had agreed. With the £2,000 she received in settlement, Mme de La Tour hired three ships to run the blockade d’Aulnay was maintaining at Saint John harbour and arrived home in the closing days of 1644.

Early in the new year, d’Aulnay launched an unsuccessful attack on Fort La Tour. Soon afterwards La Tour, cut off from supplies from France, elected to go to Boston and seek aid from the English. Word that he had left the fort and that it was now garrisoned by but 45 men was carried to d’Aulnay by deserters. He promptly decided to attack again and arrived at the Saint John River on 13 April with a force of some 200 men. His emissary, carrying the summons to surrender, was promptly dismissed by Mme de La Tour, who had assumed command of the fort and was determined to fight if she must. The ensuing battle raged for three days and has been termed by the late Dr. W. F. Ganong the most dramatic event in the history of New Brunswick.

Although casualties were relatively heavy, the action continued. By Easter Sunday – the fourth day of the siege – d’Aulnay’s bombardment had knocked out a portion of the fort’s parapet and he had been able to land a force of men with two cannons. It is said that a Swiss mercenary at the fort – Hans Vaner (or Vannier) – allowed this land force to creep up to the walls of the fortification while its defenders were resting and holding Easter service. The noise of the storming of the palisade alerted the garrison and they rushed to defend their post. Hand-to-hand clashes ensued within the confines of the fort itself, and losses on both sides were heavy. Finally, d’Aulnay called off his men and swore that he “would give quarter to all” if Mme de La Tour would capitulate. With her small garrison reduced by casualties, the fort heavily damaged, and both food and ammunition running low, Mme de La Tour concluded that her position was hopeless. She ordered her men to surrender.

The events that then transpired are shrouded in bias and personal animus, and made all the more confusing by scholastic prejudice. Consequently, we may never have a clear view of subsequent happenings. However, relatively unbiased accounts, such as that of Nicolas Denys, agree in substance. We are told that, once in possession of the fort, d’Aulnay went back on his word, disregarded the terms of capitulation, and ordered the arrest of the La Tour garrison. A gallows was erected at once and all of the soldiers captured at Fort La Tour hanged, except for one man – probably André Bernard – who agreed to be the executioner of his comrades. Madame de La Tour was forced to watch the hangings with a rope around her own neck. She herself died there three weeks later.

This gallant woman had spent but five years in Acadia, yet her position in the history of this country is assured. Hers was the distinction of being the first European woman to have lived, to have made a home, and to have raised a family in New Brunswick. Neither the perils of the sea, the dangers of war, nor the horrors of a long siege could still her courage. Here, truly, was the most remarkable woman in Acadia’s early history.

Aulnay’s version of these events is found in AN, Col., C11D, 1 (modern copies in BN, MS, NAF 9281, 9282 (Margry)). Less biased sources are Denys, Description and natural history (Ganong), 114–16 (and the sources listed therein), and Winthrop’s journal (Hosmer) in Original narratives (Jameson). Charlevoix, History (Shea). Suffolk deeds, I, 9. Couillard Després, Saint-Étienne de La Tour.

Revisions based on:

Arch. Départementales, Eure-et-Loir (Chartres, France), “État civil,” Nogent-le-Rotrou (Notre-Dame), 18 juill. 1621: www. archives28.fr (consulted 22 March 2019). Arch. Nationales (Paris, Fontainebleau et Pierrefitte-sur-Seine), MC/ET/CXIII/8.

Cite This Article

George MacBeath, “JACQUELIN, FRANÇOISE (Françoise-Marie),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jacquelin_francoise_marie_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jacquelin_francoise_marie_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | George MacBeath |

| Title of Article: | JACQUELIN, FRANÇOISE (Françoise-Marie) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | April 29, 2025 |