Source: Link

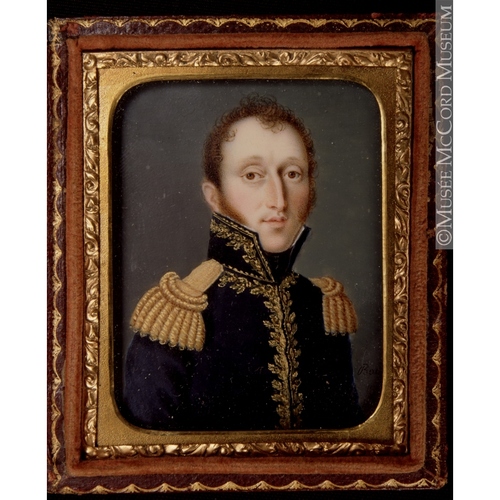

HART, AARON EZEKIEL, lawyer, militia officer, and office holder; b. 24 June 1803 in Trois-Rivières, Lower Canada, son of Ezekiel Hart* and Frances Lazarus; m. 1 Nov. 1849 his cousin Phoebe David, daughter of Samuel David and Sarah Hart, and they are thought to have had four children; d. 26 Sept. 1857.

The record shows that, at the age of 21, “Aaron Ezekiel Hart of the City of Quebec, Esquire, hath passed his Trials and was found to be qualified to the practice and profession of the Law as Advocate, Barrister, Attorney, Solicitor, Proctor and Counsel in all His Majesty’s Courts of Justice in Lower Canada, according to the certificate signed by the Lieutenant-Governor on November 6, 1824.” Hart was thus the first Jew to be called to the bar in either of the Canadas. His singular position was short-lived, however, since the following month a distant cousin, Thomas Storrs Judah (1804–95), was similarly called, as was Thomas’s brother Henry Hague Judah (1808–83) four years later. His cousin Aaron Philip Hart, son of Benjamin Hart, was admitted to the profession in 1830, his future brothers-in-law Eleazar David David* in 1832 and Moses Samuel David in 1837, and his own brother Adolphus Mordecai Hart* in 1836.

All of these men were of comparable merit, but Aaron Ezekiel had the advantage of being the first. His biography affords the opportunity for some description of this group of lawyers, who were all third-generation Canadian Jews. Aaron Ezekiel began to familiarize himself with both business and the practice of law when he entered the service of his uncle Moses Hart in 1824. He first filed claims against some censitaires of the seigneury of Bélair, and then from 1825 to 1833 frequently worked as counsel for Moses Hart in court. In 1832 he asked his uncle’s advice, “having it in contemplation to get up a Life Assurance Company [at Trois-Rivières] upon the principle of a joint stock company.” There is no indication that this plan was carried out.

Concurrently with his legal career, Hart was interested in the army. On 21 Dec. 1826 he became an ensign in Quebec’s 3rd Militia Battalion; he was made a lieutenant in the 2nd Battalion of Quebec County militia on 17 March 1831, and then captain on 4 June. Finally, on 1 April 1857 he was appointed major of the 1st Battalion of Saint-Maurice militia. The American Jewish Historical Society has a record of his admission to the Société pour l’Encouragement des Sciences et des Arts en Canada on 14 June 1827 and to the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec on 17 March 1831.

Hart was evidently quite a prominent lawyer at Quebec. Archivist David Rome considers it “a measure of Aaron Ezekiel Hart’s acceptance into Quebec Society” that in 1836 he transmitted the challenge to a duel from Clément-Charles Sabrevois* de Bleury, a member of the House of Assembly for Richelieu, to Charles-Ovide Perrault, the young member for Vaudreuil, who would lose his life the following year at the battle of Saint-Denis on the Richelieu.

Hart took great interest in the political struggles of the 1830s. With his brother Samuel Becancour he played a major role, particularly as legal adviser, in the effort to get a bill “to declare persons professing the Jewish Religion entitled to all the rights and privileges of the other Subjects of His Majesty in this Province” passed during the 1831–32 session. But this act was to give rise to varying interpretations. Thus in a letter dated 31 May 1833 Aaron Philip Hart advised his father and Moses Judah Hayes* to decline the office of justice of the peace, on grounds that there might be ambiguities about taking the oath of abjuration. Those who had had faith in this law felt somewhat foolish, particularly Samuel Becancour Hart, a new justice of the peace, who had taken his oath privately before notary Joseph Badeaux*. To clarify the situation, the assembly decided to set up a special committee under René-Joseph Kimber to study the rights of Jews in Lower Canada.

Aaron Ezekiel presented his testimony in February 1834 with vigour and self-assurance. After replying to some questions, he read a statement which he had carefully prepared. In his view the law passed in 1724 (10 George I, c.4) had guaranteed the Jews equal rights, since it provided that the litigious words “‘upon the true faith of a Christian’ should be omitted whenever a person professing the Jewish Religion presents himself to take the oath of abjuration.” Even if it were demonstrated that this statute had lapsed, “there is not one legal enactment,” he stated, “which excepts Jews from holding office in this Country” including the 1740 law on naturalization. In his opinion this law had been “improperly construed, and incorrectly comprehended,” not, however, by “the Law Officers of the Crown,” but “by a young man who has scarcely been admitted but two years to the practice of the Law, and who is far from being celebrated for the consistency of his opinions, and for the solidity of his judgment.” The reference was evidently to Aaron Philip Hart, whom in his argument Aaron Ezekiel expressly criticized for seeking to restrict to naturalization a law which was of more general intent, and which contained the same terms as the 1724 law on the oath of abjuration. Aaron Philip’s error, he explained, was that he did not read the law of 1740 in its entirety but confined himself to the title. On the question as a whole, the special committee declared Aaron Ezekiel to be right.

The attitude of the Patriote members in the matter of the rights of Jews was certainly gratifying for the Hart clan of Trois-Rivières. At the appropriate time Aaron Ezekiel and his three brothers were not unmindful of it. In 1837, while he and Ira Craig joined wholeheartedly in the meetings which were held at Quebec mainly to denounce the resolutions of Lord John Russell, Adolphus Mordecai and Samuel Becancour were active at Trois-Rivières. They spoke at public meetings and denounced the Executive Council’s assertion of absolute authority. In July and August 1837, they served on liaison committees to coordinate the action of adjacent parishes.

Nevertheless, the Jews of that period, including the Harts who lived at Montreal, generally supported the government. So too did Benjamin Hart and his eldest son Aaron Philip. But the latter, although unwilling to join in the rebellion, distinguished himself as one of the most ardent defenders of Patriotes’ rights. In December 1838 he was at the side of Joseph-Narcisse Cardinal*, who had to defend himself alone before a court martial. On 6 December Aaron Philip and his colleague Lewis Thomas Drummond* obtained permission to “make a commentary” in public on the proceedings in court. The speech of young Hart, who was only about 27, was remarkable, for after a long exposition he undertook to refute each of the solicitor general’s arguments. The court sentenced four defendants to death but recommended them to the clemency of the Executive Council, which in turn demanded that the judgement be reviewed. Finally, 10 of the 12 prisoners on trial were condemned to death. On 20 Dec. 1838, the day before notary Cardinal and his clerk Joseph Duquet* were to be executed, lawyers Drummond and Hart made a final approach to Governor Sir John Colborne*. In their opinion, “the proceedings followed in regard to the prisoners were illegal, unconstitutional, and unjust.” The governor turned a deaf ear.

Aaron Ezekiel Hart had none of the taste for business shown by his brothers Ira Craig and Samuel Becancour, nor of the venturesomeness of Adolphus Mordecai, nor of the panache and hot-headedness of his cousin Aaron Philip, but he won respect as a man of law. After practising at Quebec he settled in Trois-Rivières. In July 1852 Chief Justice John Beverley Robinson* of Toronto appointed him commissioner for receiving affidavits in Lower Canada. He was very attached to his father, Ezekiel, as well as to the Jewish community, and he was a faithful member of the Montreal synagogue, to which he gave financial support.

[The American Jewish Hist. Soc. Arch. (Waltham, Mass.) holds records relating to Aaron Ezekiel Hart’s appointments, as well as an official note from the grand lodge, dated 14 Nov. 1826, admitting him as a freemason. Hart had previously been made a member of Merchants’ Lodge No.77 at Quebec, which was listed in the grand register of the United Grand Lodge of England on 12 Dec. 1825 (see “On the early Harts,” comp. David Rome, Canadian Jewish Archives (Montreal), no.18 (1980): 415).

The report of the select committee of the House of Assembly, chaired in February 1834 by René-Joseph Kimber, notes the views expressed by Hart (L.C., House of Assembly, Journals, 1834, app.GG). There are numerous references to Hart in the new series of publications of the Canadian Jewish Archives, but some of the statements are contradictory. “On the early Harts, their contemporaries,” no.20 (1981), states on p.153 that “he died on Sept. 27, 1853, at the age of 54, and was buried in the Prison St. cemetery at Three Rivers, but, his remains were reinterred, stone still intact, in the cemetery of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews in Montreal, in 1909,” but in no.23 (1982), p.113B, David Rome suggests a death date of 1857. Again, in “Samuel Bécancour Hart and 1832,” no.25 (1982), Aaron Ezekiel Hart is mentioned at least twice, at pp.62 and 75, with the dates 1803–57. In no.18, p.414, Hart’s birth date is given as 24 June 1803 and death date as 6 Sept. 1857.

The collection Montarville Boucher de la Bruère (0032), fonds Pierre Boucher, at the ASTR contains 36 letters written by Aaron Ezekiel Hart as legal counsel for Moses Hart in the period from 1824 to 1833. The fonds Hart (0009) lists 83 different attorneys.

On Aaron Philip Hart’s role in the case of Joseph-Narcisse Cardinal, see Le Boréal express, journal d’histoire du Canada (Montréal, 1962), pp.542–43; part of the proceedings of the trial were published as Procès de Joseph N. Cardinal, et autres, auquel on a joint la requête argumentative en faveur des prisonniers et plusieurs autres documents précieux . . . (Montréal, 1839). See also P.-G. Roy, Les avocats de la région de Québec and J.-J. Lefebvre, “Tableau alphabétique des avocats de la province de Québec, 1765–1849,” La Rev. du Barreau, 17 (1957): 289. d.v.]

Cite This Article

Denis Vaugeois, “HART, AARON EZEKIEL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 25, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hart_aaron_ezekiel_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hart_aaron_ezekiel_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Denis Vaugeois |

| Title of Article: | HART, AARON EZEKIEL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | December 25, 2025 |