GREEN, GEORGE EVERITT, agricultural labourer; b. 8 Feb. 1880 in Tottenham (London), England, eldest son of Charles Green, tailor, and Amelia Green, laundress; d. 9 Nov. 1895 in Keppel Township, Ont.

Following the death of George Everitt Green in 1895, more Canadians knew about him than about any other of the children brought by British charitable agencies to work in the dominion as agricultural labourers and domestic servants. Between 1868 and 1924 more than 80,000 youngsters came to Canada as child apprentices. Boys and girls, perhaps a third of whom were orphans, were transferred from English and Scottish refuges and poor-law schools and placed with householders who had responded to newspaper advertisements offering home and farm help. Green’s circumstances showed the immigration program at its worst, and his case, widely covered in the national press and in Britain, became the most compelling set piece in polemics created by Ontario child savers and the Canadian labour movement in their advocacy of reform of the system.

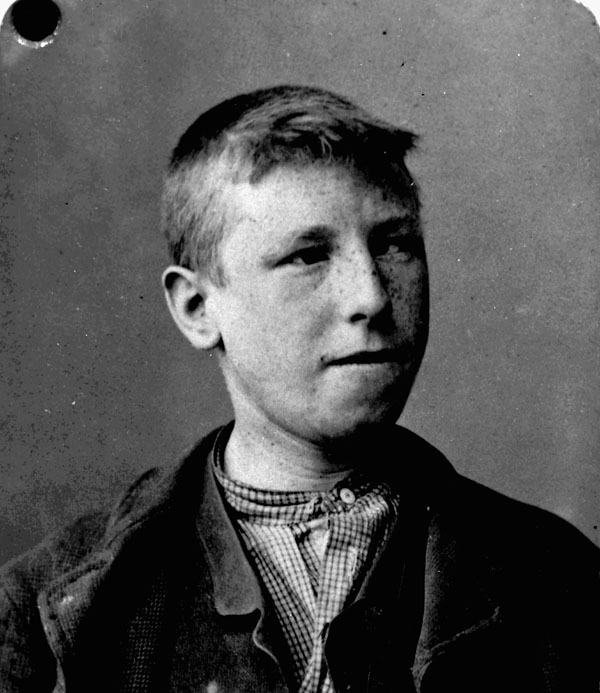

Until he was six, Green lived with his older sister, Margaret, his younger brother, Walter, and his parents in lodging-houses in the Tottenham suburb of London. In 1886 the parents deserted their children, who were admitted to the Old Parish School and then to the Enfield Farm School run by the Edmonton Poor Law Union, a local government institution. Their father died in January 1888. In May 1894 their mother induced Margaret, aged 17, to leave her job at the farm school for a place in service, and in retaliation the union discharged the boys into their mother’s care. Within a month Mrs Green was unable to pay the rent on her room, and she and the boys began to sleep rough. In July 1894 George and Walter were admitted to the East End Juvenile Mission of Dr Thomas John Barnardo at their mother’s request. George was described in the admission documents as well conducted, but with a cast in his left eye and a peculiar appearance. Eight months later, on 21 March 1895, the brothers embarked for Canada in a party of 167 boys.

George was sent on 3 April to a bachelor farmer in Norfolk County, Ont., who returned him to the Barnardo receiving home in Toronto within the trial period of a month because the boy’s defective vision meant that he could not drive a team. On 7 May, Green was dispatched to a second place, near Owen Sound, to live with a single woman, Helen R. Findlay. Since her brother’s death the previous summer, Findlay had run the family farm alone. Before that time, two Barnardo boys had been placed on separate occasions with the Findlays. Neighbours who saw Green soon after he arrived described him as clean, healthy, quiet, and backward. Findlay, who after her brother’s death had been observed doing field and barn work the community regarded as inappropriate for women, they viewed with suspicion.

Seven months after his arrival on the Findlay farm, on 9 Nov. 1895, George Everitt Green died. A coroner’s inquiry found that his death resulted from “ill-treatment at the hands of Ellen R. Findley, and from her not giving him proper care and treatment, food and nourishment during his sickness in her house,” and Findlay was charged with manslaughter. In the ensuing trial, neighbours reported that for several months they had observed the boy inadequately clothed and fed, forced by physical violence to do work beyond his strength, and made to sleep in the barn as punishment. None, however, had seen fit to break community solidarity and attempt to assist him. Medical testimony was conflicting. Green had been unable to move from his bed for a week before his death. His frame was emaciated, his limbs gangrenous. His body bore wounds caused by physical abuse. An autopsy of his lungs showed a previous history of tuberculosis. The question for the jury became did Green die as a result of criminal neglect and physical assault by Helen Findlay, or were her actions reasonable chastisement of an inadequately prepared farm servant and his infirmities a consequence of hereditary or pre-emigration conditions? The jury was unable to reach a decision. No further record of the case has been found.

Publicity surrounding the inquest and the trial influenced both federal and provincial policy on child immigration. The labour movement became involved not only because it was interested in the well-being of the young labourers but also because it was concerned about their effect, as part of an increasing stream of immigration, on Canadian wage rates. In 1897, responding to labour’s requests, the new Liberal government of Wilfrid Laurier* appointed a representative of the labour movement, Alfred F. Jury*, as Canadian immigration agent at Liverpool, with special responsibility to scrutinize the actions of the British child emigration homes. In Ontario, John Joseph Kelso*, the provincial superintendent of neglected and dependent children, and his supporters in the child-saving movement argued that no youngsters should be as casually placed as Green had been. Their pressure for reform led in 1897 to passage of the Juvenile Immigration Act, which required more careful record-keeping and screening of child immigrants and annual inspections of them in their Canadian situations. This act was subsequently replicated in Manitoba, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, the other provinces in which substantial numbers of British children were placed.

NA, MG 28, I 334, book 24: 72 (mfm.); RG76, Blai, 124, file 25399. Joy Parr, Labouring children: British immigrant apprentices to Canada, 1869–1924 (London and Montreal, 1980), 54–58.

Cite This Article

Joy Parr, “GREEN, GEORGE EVERITT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/green_george_everitt_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/green_george_everitt_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Joy Parr |

| Title of Article: | GREEN, GEORGE EVERITT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | January 2, 2026 |