Source: Link

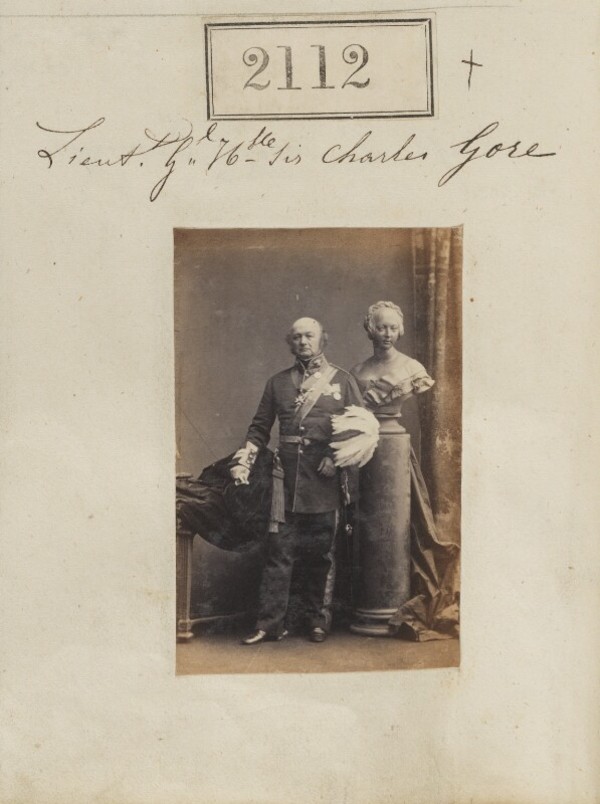

GORE, Sir CHARLES STEPHEN, soldier; b. 26 Dec. 1793, son of Arthur Saunders Gore, 2nd Earl of Arran, and Elizabeth Underwood; m. 13 May 1824 Sarah Rachel, daughter of James Fraser*, legislative councillor of Nova Scotia, and they had six children; d. at London, England, 4 Sept. 1869.

The Honourable Charles Stephen Gore entered the army in 1808, and on 4 Jan. 1810 was promoted to a lieutenancy in the 43rd Regiment. Joining the 43rd in Spain in July 1811, he participated in the investment and storming of the great fortresses of Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz, and in all the actions of the Light Division from 1812 until 1814.

Appointed in 1812 aide-de-camp to Major-General James Kempt*, in August 1814 he accompanied him to Canada, where Kempt was appointed to command the Montreal District. He returned to England on the general’s recall, and served him with gallantry during the Waterloo campaign. On 15 June 1815 he had been gazetted a captain in the 85th Regiment in which he was promoted to a majority on 21 Jan. 1819. After five years of regimental duty, which included the capture and occupation of Paris, Major Gore was seconded as adc to Kempt on the latter’s appointment to the command of Nova Scotia and its Dependencies. They reached Halifax on 2 June 1820. Promoted lieutenant-colonel on 18 Sept. 1822, Gore then served in Jamaica as deputy quartermaster-general until 1826 when, on exchange, he became deputy quartermaster-general for British North America. Promoted major-general on 9 Nov. 1846, Gore became, as of 1 April 1847, the general officer commanding Canada’s Eastern District at Montreal.

During the insurrection of 1837, Gore, after nearly 20 years on staff, played a conspicuous if controversial role. Appointed by the commander of the forces, Sir John Colborne, to lead an expedition against Saint-Denis and Saint-Charles, dissident villages some 20 miles east of Montreal on the Richelieu River, he arrived at Sorel by steamer on 22 November, accompanied by a deputy sheriff representing the civil power. Gore had at his disposition an infantry column composed of four companies of the 24th and 32nd regiments, a small detachment of artillery with a howitzer, and a token troop of the Royal Montreal Cavalry (also known as the Montreal Volunteer Cavalry). He was to proceed against Saint-Denis, headquarters of Dr Wolfred Nelson, one of the ablest of the insurgent chiefs, while Lieutenant-Colonel George Augustus Wetherall advanced north from Fort Chambly against Saint-Charles.

Despite freezing rain and next to impassable roads, Gore determined on a night march in order to surprise his objective, and at 10 p.m. his slender column, now reinforced by two companies of the 66th Regiment, was en route. He thus missed a courier, Lieutenant George Weir of the 32nd, who had been dispatched by Colborne with urgent orders for his field commander to await reinforcements or, if engaged, to retire in the face of superior force. To avoid insurgents he thought to be at Saint-Ours, Gore took a minor inland road and the nearly exhausted British force did not reach Saint-Denis until nearly 10 a.m. on the 23rd, just when Lieutenant Weir, who had been arrested during the night, was sadistically murdered near the south end of the village. Gore found Nelson’s men – probably some 700, but only some 120 with firearms of any description – fully alert and blocking his advance from two strong stone buildings and a stout street barricade. Although his own strength did not exceed 300, Gore attacked. By 3 p.m., however, his infantry had been outgunned, his howitzer had proved useless, ammunition was in perilously short supply, rations were non-existent, and he had suffered some 22 casualties. Moreover, George-Étienne Cartier* had just crossed the Richelieu with 100 well-armed reinforcements, and Nelson had promptly ordered a counter-attack.

The defeated British limped into Sorel on 25 November, the day of Wetherall’s victory at Saint-Charles. Gore left for Montreal later that day, but by the evening of the 30th, his original command reinforced by five additional companies (three of the 32nd, one of the 24th and the 83rd), two guns, and 12 Montreal cavalry, he was back in Sorel for a second attack on Saint-Denis. On Saturday, 2 December, he re-entered Saint-Denis unopposed. There followed two days of unrewarding searches, looting, and burning, and by Sunday night some 50 buildings had apparently been gutted or destroyed. According to a reputable observer, Lieutenant E. Montagu Davenport, the regulars were set to work to destroy the property of known insurgents, but Gore had issued strict orders against pillage, and a picket patrolled the streets to prevent it. Nonetheless the troops got out of hand, and many houses were wantonly destroyed or at least set alight. While Dr Nelson’s distillery was being demolished, Davenport noted, houses along the road to Saint-Ours were burnt, an act of indiscriminate arson he attributed to the vengeance of the volunteers.

Early on the 4th Gore set out for Saint-Hyacinthe in pursuit of Louis-Joseph Papineau* and other insurgent leaders. Later that same day, at Saint-Denis, the hideously mutilated body of Lieutenant Weir was discovered. Two days later Gore proceeded to Sorel, leaving three companies to garrison Saint-Denis, and returned to Montreal on the 7th with the 32nd who were bearing Weir’s body.

Colonel Gore suffered considerable censure, primarily in Patriote circles, because of the burnings in Saint-Denis. In fact, in February 1849, he was viciously attacked on the subject by Henry John Boulton during the legislative debates on the Rebellion Losses Bill. Sir Allan Napier MacNab rose to his defence, but the charge was not given quietus until, in a subsequent session, Boulton not only retracted but asserted he had Gore’s authority to state that he had used every exertion to prevent the burnings and had given orders for recalcitrants to be hailed before drumhead courts martial and flogged. Curiously the responsibility for orders to destroy insurgent property never became a public issue, but as similar burnings took place at Saint-Charles and Saint-Eustache, it must be assumed that such orders emanated from headquarters itself [see John Colborne]. Writing in the early 1850s, the historian Robert Christie* attempted a rational explanation of the Saint-Denis and similar incidents: “There are occasions when the passions of men become uncontrollable by human authority and, unhappily, this was one of them.” The truth of this observation is obvious, yet the fact remains that a military commander is indisputably responsible for the conduct of his men if, in fact, he is physically and mentally able to exercise that responsibility.

On 4 July 1849, Gore was posted to Kingston as commander, Canada West. However, during the last years of his tenure in Montreal he had not enjoyed the full confidence of Lord Elgin [Bruce] who wrote of Gore, at a time when passage of the Rebellion Losses Bill was causing concern for order, that it was “generally believed that his judgement could not be relied on in difficulties.” But Kingston was an eminently “safe” posting, and after three uneventful and popular years there Gore was ordered to Halifax on 20 Sept. 1852 with the command of Nova Scotia and its Dependencies. In June 1855 he finally embarked for the United Kingdom, on recall. His final promotion was to general in February 1863, and his last appointment, dated December 1868, was to the lieutenant governorship of Chelsea Hospital in London. His honours included the Peninsular medal (nine clasps), the Waterloo medal, cb (1838), and gcb (1867).

It was said of Colonel Gore in 1837 that he was a better qmg than he was a field commander. But his personal bravery was never questioned, his long career on staff was successful, if not brilliant, and he proved himself an effective, considerate, and much respected district commander in British North America.

PAC, RG 8, I (C series), 1275. PRO, WO 17/1518, 17/1536–58, 17/1830–35, 17/2367–69, 17/2399–402 (mfm. at PAC). E. M. Davenport, The life and recollections of E. M. Davenport . . . written by himself; “notes of what I have seen and done,” from 1835 to 1850 (London, 1869), 49–65, 69–72. Elgin-Grey papers (Doughty), I, 166. Daniel Lysons, Early reminiscences, with illustrations from the author’s sketches (London, 1896), 69–76. Montreal Gazette, November–December 1837, February–March 1849. Boase, Modern English biog., I, 1184. Burke’s peerage (1967), 105. DNB. G. B., WO, Army list, 1809–39. Hart’s army list, 1840–69. Historical records of the 91st Argyllshire Highlanders, now the 1st battalion Princess Louise’s Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders . . . , comp. G. L. J. Goff (London, 1891), 336. L.-N. Carrier, Les événements de 1837–1838 (Québec, 1877), 75–78, 82–85. Christie, History of L. C., IV, 451–70. William Kingsford, The history of Canada (10v., Toronto and London, 1887–98), X, 53–61, 68. Joseph Schull, Rebellion: the rising in French Canada, 1837 (Toronto, 1971), 73–77, 79, 84–88.

Cite This Article

John W. Spurr, “GORE, Sir CHARLES STEPHEN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gore_charles_stephen_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gore_charles_stephen_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | John W. Spurr |

| Title of Article: | GORE, Sir CHARLES STEPHEN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | December 19, 2025 |