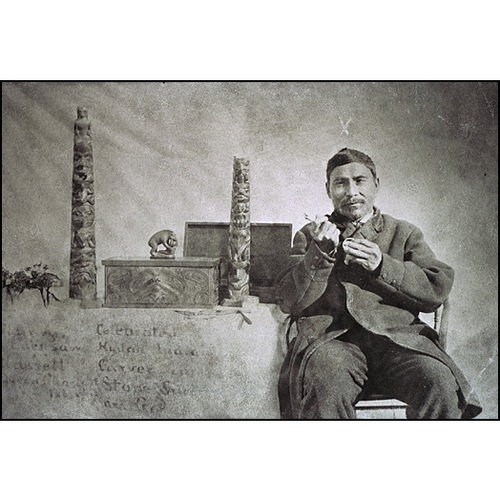

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

EDENSHAW, CHARLES (also named Da•axiigang (Dahˀégin, Tahayghen, Takayren), Skil’wxan jas, N∂ngkwigetklałs; succeeded to the chiefly title of Eda’nsa (Itínsaw, Edensaw, Ee-din-suh, Idansu, Idinsaw)), Haida artist and chief; b. c. 1839 in Skidegate (B.C.), son of Qawkúna of the Sdast’aas Eagle lineage and her husband K’łajang-k’una of the Nikw∂n qiwe Raven lineage; d. 1920, probably on 12 September in Masset, B.C.

Charles Edenshaw was heralded during his lifetime by the Haida people and by collectors and anthropologists as one of the most accomplished Haida carvers, and he continues to be the best known late-19th-century Haida artist. He was born during a period when his people’s culture was experiencing an economic and artistic florescence spurred by the increased wealth resulting from the European and Euro-American fur trade at mid century; he survived the devastating smallpox epidemic of 1862 and the later period of missionizing and colonizing by Euro-Canadians. By the time that he assumed the title Chief Eda’nsa in 1885, potlatching had been outlawed in Canada and much of the social and ceremonial role that had accompanied his title had been suppressed by missionaries and government agents. Edenshaw was able to focus on his art. He worked as an artist well into the 20th century, developing a personal style that is renowned for its originality and innovative narrative forms, yet acclaimed for its adherence to the sophisticated formline-design principles that characterize Haida art. In 1902 the collector Charles Frederick Newcombe* described him as “the best carver in wood and stone now living.”

Little is known of Edenshaw’s childhood. As an infant he was named Da•axiigang, meaning “noise in the housepit.” His parents were able to potlatch extensively, as is indicated in another of his names, N∂ngkwigetklałs (“they gave ten potlatches for him”), which was conferred at his parents’ final potlatch. According to custom, he was tattooed at these ceremonies on his back, arms, legs, chest, and hands. His daughter Florence Edenshaw Davidson remembered eagle, sea wolf, and frog tattoos. While growing up Edenshaw may have learned to carve canoes from his father, who was known as an expert canoe maker. His father, it is said, died when he was still a boy.

It was customary among the Haida for the eldest son of a chief’s eldest sister to move on reaching maturity to the house of his uncle, whom he was in line to succeed as chief. Florence Davidson recalled that “dad was about eighteen or nineteen when he came to Masset. His uncle, Albert Edward Edenshaw [Eda’nsa*], wanted him, so he came here.” Eda’nsa, the hereditary chief of the Sdast’aas Eagle lineage, had moved his family from Kiusta to the village of Kung, east of Kiusta on the north coast of Graham Island in the Queen Charlottes, around 1853. It is probable that, while the family were frequently in Masset, their principal residence was in Kung until the 1880s.

When Eda’nsa married his second wife about 1865 he brought her niece K’woiy∂ng to Kung and adopted her as his daughter. Around 1873 K’woiy∂ng came of age and she and Da•axiigang married. The couple were likely still living in Kung at this time, though they doubtless maintained residences during the 1870s in Kung, Yatza, and Masset. In the early 1880s they inherited a house in Masset from the widow of one of Da•axiigang’s uncles, and it was probably then that they moved their principal residence there. On 27 Dec. 1885 they were baptized in Masset, taking the names Charles and Isabella after European nobility, and immediately afterwards they were remarried in church. According to Florence Davidson, Eda’nsa “put my dad in his place while he was still living,” meaning that he gave him his name. “When my dad married my mother in the church that’s when his uncle gave him the name Edenshaw.”

His daughter related that Charles Edenshaw had begun carving argillite and silver in Skidegate one winter when he was sick, at about age 14. The carving of argillite, a black carbonaceous shale, had been started there by an earlier generation of Haida artists, who produced tobacco pipes for sale as early as the 1820s and portraits of Euro-American maritime fur traders. Edenshaw may have initiated the carving of precious metals, however. According to the Anglican priest Charles Harrison, who ministered at Masset in the 1880s, “Chief Edenshaw” was the first Haida artist to attempt to manipulate silver and gold. Little is known about Edenshaw’s work before 1880, but it can be assumed that it included poles, masks, frontlets, chests, and feast dishes, the full range of Haida art made for ceremonial use. Six full-sized poles have been attributed to him, although at least two are now known to have been the work of his uncle Eda’nsa. No argillite carvings have yet been attributed to the early stages of his career.

By the time he and his wife moved to Masset, Charles Edenshaw’s style was fully developed, and he made his living from his art, not needing to supplement his income through fishing or hunting as many Haida artists did. From the known attributions of his work, it would appear that his most productive period was from 1880 to 1910. As his uncle had before him, in the spring and summer he made frequent visits with his family to places such as Port Essington, Fort Simpson (Port Simpson), and Victoria and Juneau, Kasaan, Klinkwan, and Ketchikan in Alaska, where he would carve and sell his work and Isabella would make baskets for sale and take employment in canneries. For some years Charles carved in Victoria all winter long. Later he used a shed behind his house in Masset and, after the children were grown, he carved in the house.

The carvings he produced included model poles and houses, chests, bowls, and platters in wood and argillite and model canoes, masks, and frontlets in wood, all intended for sale to non-natives. In addition, he painted designs on basketry hats and plaques made for sale by Isabella. There is no evidence that silver and gold jewellery was made by Edenshaw for outsiders, and it is probable that such objects were carved exclusively for Haida people to display their family crest. Other objects he crafted that are known to have been used within the Haida community include wooden settees, cradles, and stone grave monuments. A number of items may have been intended either for use or for sale, such as canes with silver ferrules and ivory handles. However, the vast majority of objects attributed to him were made for sale. George Cunningham’s store in Port Essington handled both Charles’s and Isabella’s work; collectors such as Charles Newcombe came to their home to buy.

In 1896 Charles and Isabella’s only living son, Robert, was drowned in a swimming accident, a terrible blow to the entire family, in which five of eight children had already died. The loss to Charles must have been deeply felt, for his son was a promising carver. Florence was born the next month and, according to her, “all the people” were disappointed she was not a boy. As it turned out, she became a treasured child to Charles, since she was considered the reincarnation of his mother, his mother’s “second birth.” Charles and Isabella would have two more daughters, one of whom died young.

It was during this period that Edenshaw was consulted and commissioned by a series of collectors and anthropologists whom he met in Port Essington, Kasaan, Victoria, and Masset. In 1897, at Port Essington, he gave Franz Boas* the information and drawings that were published in 1927 in Boas’s classic Primitive art. The tattoo designs commissioned by Boas at this time were later published by the anthropologist John Reed Swanton of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. For Swanton in 1901 Edenshaw made models of eight poles, two model houses (one of which had only the frame and interior post), and one model canoe. After Swanton’s return to New York, he commissioned a mask from Edenshaw through his cousin Henry Edenshaw.

The major collections of Charles Edenshaw’s work are to be found in the American Museum of Natural History, the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria, the University of British Columbia’s Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver, the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Hull, Que., and the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, England. The first exhibit to feature Edenshaw’s work as “fine art” and to identify him as an artist alongside Emily Carr*, Paul Kane*, and Alexander Young Jackson* was the Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art that was mounted at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa in 1927 and later travelled to the Musée du Jeu-de-Paume in Paris. Though the so-called “Canadian artists” are listed separately with the titles of their works in the small catalogue to this exhibit, the native artists are not. Only their works are listed, with explanatory descriptions. Under “No. 112, slate carvings,” the text reports that “many of the best pieces” are the work of Edenshaw.

Marius Barbeau* was principally responsible for bringing argillite carving to the attention of the outside world through his publications Haida carvers and Haida myths in the 1950s. He was the first to record the biographies of Haida artists and to identify individual artists with their work. Unfortunately, many of his attributions were incorrect. Much has been done to clarify the record, starting with the 1967 exhibit Arts of the Raven at the Vancouver Art Gallery, which featured an entire gallery devoted to items by or attributed to Edenshaw (66 objects). Interest has continued ever since.

The most detailed discussion of Edenshaw’s art was published by Bill Holm in 1981. He was the first to attempt to analyse a progression in Edenshaw’s work and to differentiate it from the output of several contemporary Haida artists in Skidegate and Masset whose work had been confused with his. The closest in style – and in family – to Edenshaw was his stepfather, John Robson. Holm suggests that Edenshaw’s two-dimensional design style, which is characterized by medium- to narrow-width formlines, very rounded Us and ovoids, a concentricity in the ovoid complexes, and stacked U complexes, among other things, was fully formed by 1879 when two bracelets made by him, now in the Canadian Museum of Civilization, were collected. An older two-dimensional design style is described as having “less smoothly flowing formlines . . . more angular ovoids and somewhat awkward junctures,” resulting in ground and tertiary forms that are “less integrated with the whole composition.” Holm mentions as examples of this earlier style several argillite carvings including the bear’s-mouth house models in the Vancouver Museum and the Alaska State Museum in Juneau. He describes the frog settee in the Royal British Columbia Museum as representing a transitional period, angular in style but displaying features such as stacked Us and ovoids containing circular, mouthless salmon-trout’s heads, elements that appear frequently in later pieces. Though this settee was collected by Charles Newcombe in 1901, it must have been made before 1879.

Charles Edenshaw’s carvings often explore variations on mythical or crest-figure themes, such as the Raven stories. An argillite platter in the Seattle Art Museum is one of three platters by him that illustrate the sexing of human beings, part of the story explaining the origin of humankind in the Raven mythology. The other two, both received in 1894, are in the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin and the Field Museum of Natural History. These innovative platters are the first known representations of this old Raven story in Haida art (a silver cane ferrule by Edenshaw in the Pitt Rivers Museum also illustrates the myth) and they typify Edenshaw’s expansion of the Haida repertoire and mastery of a new narrative style. The story follows in sequence from the more famous episode in which Raven discovers humankind emerging from a clam shell. According to one version of the myth, at this point all the human beings were little boys. Hearing of monster-like beings which resembled rock chitons but were really female genitalia, Raven decides to capture them. Animating a shelf fungus to act as steersman of his canoe, he successfully spears the monsters and returns, throwing them at the human beings. Half of them stick, changing the boys to girls. All three platters by Edenshaw show Raven in human form (human face, raven beak, human arms, and raven legs), wearing a ringed hat and holding a spear, sitting in a canoe with the fungus man, also depicted as a human figure, at the stern. The canoe and the hat are decorated with elaborate formline designs. Below the canoe is the monster, with large round eyes and sharp teeth. All three platters reveal Edenshaw’s ability to master the design problems inherent in circular compositions while never repeating himself; they are eloquent variations on a theme.

Edenshaw’s eyesight and health are said to have deteriorated after 1910. His art production probably declined in quality and in quantity during the last ten years of his life, although he reputedly carved until the end. According to his great-grandson Robert Charles Davidson, he said to his wife before he died, “When I come back, I don’t ever want to carve again.” Charles Gladstone, a nephew who was in line to inherit the name of Chief Eda’nsa, chose not to assume this title on Edenshaw’s death. Consequently it went to two men, Alec Yeltatzie and James Sterling.

Edenshaw’s career remains remarkable for the quality and range of objects produced over some 67 years, as well as for its stylistic and narrative innovation which expanded Haida style beyond its traditional boundaries. His work continues to inspire Haida artists, including William Ronald (Bill) Reid, Charles Gladstone’s grandson, and brothers Robert Charles and Reg Lester Davidson. As Robert Davidson has commented, “It seems like Edenshaw knew the spirit of the Haida nation, and from stories of my grandmother, he spent his whole life carving, his whole life creating. . . . He had such a mastery of all the mediums that it was a joy, it still is a joy to look at his work.”

American Museum of Natural Hist., Anthropology Arch. (New York), J. R. Swanton, letters to Franz Boas, 1900–1. BCARS, Add. mss 1077, 55, file 10. Univ. of Wash. Libraries,

Cite This Article

Robin K. Wright, “EDENSHAW, CHARLES (Da•aӿiigang (Dahɨégɨn, Tahayghen, Takayren), Skɨl’wxan jas, N∂ngkwigetklaīs; Eda’nsa (Itɨnsaw, Edensaw, Ee-din-suh, Idansu, Idinsaw)),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/edenshaw_charles_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/edenshaw_charles_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robin K. Wright |

| Title of Article: | EDENSHAW, CHARLES (Da•aӿiigang (Dahɨégɨn, Tahayghen, Takayren), Skɨl’wxan jas, N∂ngkwigetklaīs; Eda’nsa (Itɨnsaw, Edensaw, Ee-din-suh, Idansu, Idinsaw)) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | April 25, 2025 |