Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

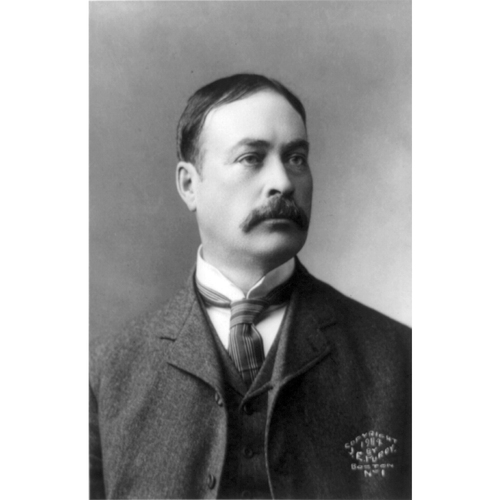

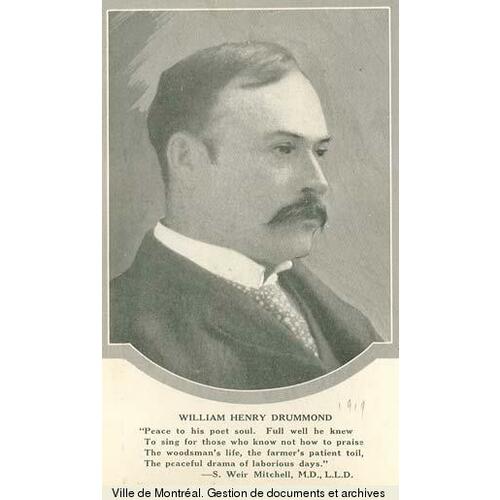

DRUMMOND, WILLIAM HENRY (known until 1875 as William Henry Drumm), telegraphist, physician, poet, professor, and public lecturer; b. 13 April 1854 near Mohill (Republic of Ireland), son of George Drumm and Elizabeth Morris Soden; m. 18 April 1894 May Isobel Harvey in Savanna la Mar, Jamaica, and they had three sons, one of whom survived infancy, and one daughter; d. 6 April 1907 in Cobalt, Ont.

The eldest of four sons born to an officer in the Royal Irish Constabulary and his wife, William Henry Drumm spent his early years in County Leitrim. He attended school in Tawley, where his parents had moved shortly after his birth. Sometime in 1863–64 the family returned briefly to Mohill. According to May Isobel Drummond, after George Drumm was dismissed from the police force because of a quarrel with Lord Leitrim over “the Landlord system,” he had “a paralytic stroke from which he never really recovered.” Disgusted with conditions in Ireland and worried about the family’s future, he and his wife decided to emigrate with their children to Lower Canada; they arrived in Montreal in the summer of 1864. In February 1866 Drumm died and his family, left without even his small pension, faced financial hardship.

In order to survive, Mrs Drumm opened a store in the front room of their house, the boys all sold newspapers, and, when he was 14, William Henry left school and became an apprentice telegraphist. For the next several years he worked as a telegraph operator during the summers at Bord-à-Plouffe (Laval) on the Rivière des Prairies and in the winters in Montreal. He earned about $50 a month, most of which he turned over to his mother, who used it to keep his brothers in school. In 1875, having been convinced by a cousin that “the name Drumm was but a Corruption of the name Drummond our ancient family name,” he officially changed his surname and that of his mother and brothers to Drummond.

In 1876–77 Drummond attended the High School of Montreal. He enrolled in the faculty of medicine at McGill College in 1877, but for various reasons he failed his second year. In 1879 he transferred to the medical faculty of Bishop’s College, located in Montreal [see Francis Wayland Campbell], and he completed his studies there. For four months in 1885 he interned as a surgeon at the Western Hospital of Montreal and he then practised in the Eastern Townships, first at Stornoway and then at Knowlton. In 1888 he returned to Montreal, where he set up a practice in the family home.

The routines that were to govern much of the rest of Drummond’s life were soon established. He was a conscientious doctor who cared deeply about his patients, often to the detriment of his pocketbook. His papers contain many indications of his charity. His career was furthered by his appointments at Bishop’s: in 1893 as professor of hygiene and in 1894 as assistant registrar and professor of medical jurisprudence; he would hold this last post until the medical faculty amalgamated with McGill’s in 1905. In 1895 he became associate editor of the Canada Medical Record. Three years later at a meeting in August of the Canadian Medical Association he read a paper entitled “Pioneers of medicine in the province of Quebec.”

In his leisure time he bred and showed Irish terriers; he was an active member of the Montreal Kennel Club and the Irish Terrier Club of Canada. As often as possible he went fishing, his favourite sport since childhood, and hunting, although he did not like to kill animals. The Laurentian Club at Lac la Pêche and the St Maurice Club on Lac Wayagamac were two of his preferred haunts; the latter was particularly appealing because it was close to the Radnor ironworks, operated by the Canada Iron Furnace Company Limited, in which his brothers George Edward*, John James, and Thomas Joseph, all of whom were to become influential businessmen, were actively involved. Above all Drummond remained close to his mother and his brothers.

When Drummond was 40, he married May Isobel Harvey, a native of Jamaica, whom he had met at the Laurentian Club in September 1892. After their marriage they made frequent trips between Montreal and Jamaica. Following the death of their first child, Mrs Drummond spent several months at Savanna la Mar in 1895–96. Their second son, Charles Barclay, was born in July 1897, just before the publication of The habitant and other French-Canadian poems, the volume that transformed Drummond into one of the most popular authors in the English-speaking world.

Drummond had composed what became his best-known poem, “The wreck of the ‘Julie Plante,’” in the late 1870s. His elderly friend Gédéon Plouffe, attempting to persuade the young telegraphist to come in off the Lac des Deux Montagnes in a windstorm, had reiterated “An’ de win’ she blow, blow, blow!” These words, wrote May Isobel Drummond, “rang so persistently in [Drummond’s] ears that, at the dead of night, unable to stand any longer the haunting refrain, he sprang from his bed and penned” the lines that were “to be the herald of his future fame.” According to his wife, Drummond located the shipwreck on Lac Saint-Pierre because he was unable to find “anything to rhyme with ‘Lake of Two Mountains.’” With its clever mixture of English and French words, strong rhythms, masculine rhymes, tragicomic tone, and homely moral that “You can’t get drown on Lac St. Pierre / So long you stay on shore,” the poem was an instant success. Although it was apparently not published until several years later, it circulated widely in manuscript and typescript and became a popular piece for recitation. By the 1890s its setting had been adapted to other lakes and rivers in North America and the name of its creator had been so completely forgotten that various people disputed Drummond’s authorship when it appeared in The habitant and other French-Canadian poems. Throughout the 20th century it has been his most frequently anthologized poem.

Drummond had continued to compose occasional pieces and poems for circulation to friends. In the early 1890s his verses began appearing in Canadian periodicals and he made his début as a reciter of his own poetry. By the middle of the decade, especially with the encouragement of his wife and his brother Thomas Joseph, he was planning a volume. He had most likely also been prompted by poet Louis Fréchette, whom he had met in January 1896. It was Fréchette who arranged the meeting of Drummond and Madame Emma Albani [Louise-Cécile-Emma Lajeunesse*], when she visited Montreal in 1896. Drummond dedicated his poem “The grand seigneur,” set to music by Percival John Illsley, to this famous Canadian singer, who included it in her repertoire.

Drummond’s book did not appear in 1896. Intimations of its existence, however, had already aroused some interest. The publisher Fleming Hewitt Revell of Chicago, who had read some of his poems and had heard others “most highly commended,” asked the poet in December to submit the manuscript. In the end, however, Thomas Joseph Drummond took the manuscript, containing 23 poems and several illustrations by Frederick Simpson Coburn*, to New York City and arranged its publication with G. P. Putnam’s Sons. Before The habitant and other French-Canadian poems was issued in November 1897, Fréchette had been engaged to compose an introduction in French, which Drummond, writing to him in October 1897, called “beautiful and masterly. . . . I sincerely believe now that the volume will not only have a largely increased Sale but be really productive of great good.”

The “good” that was Drummond’s object is defined in the opening paragraphs of the preface. He noted that he had not written his verses “as examples of a dialect, or with any thought of ridicule.” Having lived beside French Canadians most of his life, he had “grown to admire and love them.” Although the English-speaking public might be familiar with the urban French Canadian, it “had little opportunity of becoming acquainted with the habitant.” Drummond therefore “endeavoured to paint a few types.” “It has seemed to me that I could best attain the object in view by having my friends tell their own tales in their own way, as they would relate them to English-speaking auditors not conversant with the French tongue.”

The habitant and other French-Canadian poems was both a popular and a critical success. Before the end of December 1897 four impressions of the edition had been issued; by the time Drummond died, as many as 38,000 copies had been printed. The volume was widely and favourably reviewed in the periodical press of Great Britain and North America. The poems themselves became subjects of detailed critical comment. It is unclear how much money Drummond made from sales, but the attention that he received both enabled and forced him to change his life. Editors constantly solicited poems and prose for their newspapers, magazines, and anthologies; Putnam’s as well as other publishers urged him to prepare additional volumes; and Drummond continually received invitations to give lectures and readings in various parts of North America.

With all these demands he did his best to comply. Three more volumes were published by Putnam’s: Phil-o-rum’s canoe and Madeleine Vercheres; two poems (1898); Johnnie Courteau and other poems (1901); and The voyageur and other poems (1905). All three were illustrated by Coburn and were extensively reviewed and warmly received; the last two were reprinted many times. In addition to his public appearances in Montreal, Drummond undertook various lecture tours in the United States and Canada. In 1901, for example, after a meeting of the Canadian Medical Association in Winnipeg in August, he gave performances in Vancouver, Victoria, and New Westminster. In 1902 he spent part of the summer in Great Britain, where he was entertained by several authors, including Robert Barr* and Horatio Gilbert Parker*. All these activities brought him fame and honours, if not a great fortune. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature of the United Kingdom in 1898 and a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1899. In 1902 he was awarded an honorary degree by the University of Toronto and in 1905 another would be conferred on him by Bishop’s College.

In August 1904 Moira, Drummond’s only daughter, was born; her birth was followed in September by the death of his third son, William Harvey, aged three. One of his most famous poems, “The last portage,” which appeared in The voyageur and other poems, came to him as a result of a dream that he had on Christmas Eve 1904 while he was still mourning the boy’s death. Lines such as “An’ oh! mon Dieu! w’en he turn hees head / I’m seein’ de face of ma boy is dead – ” and “Was it a dream I dream las’ night / Is goin’ away on de morning light?” demonstrate the combination of dialect, emotion, and mystery that makes Drummond’s best poetry so powerful, and so popular.

Drummond was still in demand as an entertainer, but the loss of his child, coupled with his mother’s death in April 1906, appears to have affected him greatly. In 1905 he closed his medical practice in Montreal. Until his death he commuted frequently between Montreal and Cobalt, where he and his brothers had acquired an interest in silver mines. He spent most of the winter of 1906–7 in Cobalt combating a smallpox epidemic. During this time he was not always well himself. He returned to Montreal in early March, in time to take his wife on a trip to New York and Washington and to read “We’re Irish yet” to the annual dinner of the St Patrick’s Society in Montreal on 18 March 1907. Then he was off again to Cobalt. He died there of a cerebral haemorrhage. Two days later, on 8 April 1907, he was buried in Mount Royal Cemetery, Outremont, after a funeral at St George’s Church (Anglican), where he had worshipped for most of his life.

At the time of his death and for years afterwards Drummond was mourned as a man, and known and respected as a poet. In 1908 The great fight: poems and sketches, a collection of 20 poems and two sketches, with a short biography by his widow and illustrations by Coburn, was edited by her and published by Putnam’s. The poetical works of William Henry Drummond appeared in 1912. Until well into the 1920s Drummond and his poetry remained important components of the canon of English Canadian literature. Since then his position has become problematical. In 1976, for example, Robert Gordon Moyles characterized Drummond’s poetry as, “though widely read, . . . not truly representative of his own era and . . . now out of fashion.” Already a victim of the attack of modernists on late-19th-century poetry, Drummond’s reputation has been further jeopardized because of a fear that his portrayal of the “habitant” will stir resentment among Québécois. Yet, according to Lee Briscoe Thompson, who lamented the removal of Drummond from the 1974 edition of Canadian anthology, the “shelving” of this “people’s poet” was unfortunate, for Drummond represents a sincere attempt to articulate a myth of cultural mosaic. The achievement of his poems lies not only in their sympathetic portrayal of rural French Canadians but also in their evocation of thoughts and feelings about the human condition and in their representation of, and experimentation with, what might be called a uniquely Canadian/canadien language.

In addition to the volumes of Drummond’s poetry cited in the biography, there exists a collection selected and introduced by Arthur Leonard Phelps, Habitant poems (Toronto and Montreal, [1959]; repr. 1970). Drummond’s poems have also been frequently anthologized, and they are widely disseminated in the periodical press of North America, particularly that published in the last decades of the 19th century and the first decade of the 20th.

The main collection of Drummond’s papers is held by the McGill Univ. Libraries (Montreal), Osler Library, at Acc. 439; this repository also holds, at Ace. 506, a recording of a 1974 CBC radio broadcast devoted entirely to Drummond. There is additional documentation on him in several manuscript groups at the NA, most notably in MG 30, A88.

From the 1890s Drummond has been routinely included in Canadian biographical dictionaries and Canadian literary dictionaries and histories, for example in Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898), Standard dict. of Canathan biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), and 7%e Oxford companion to Canadian literature, ed. William Toye (Toronto, 1973); there is also an article on him in the DNB. J. F. Macdonald, William Henry Drummond (Toronto, [1923?]), is the sole book-length study of the poet.

L. J. Burpee, “W. H. Drummond: interpreter of the habitant,” Educational Record of the Prov. of Quebec (Quebec), 61 (1945): 208–12, reissued as “W. H. Drummond [1854–1907],” Leading Canadian poets, ed. W. P. Percival (Toronto, 1948), 71–78. R. H. Craig, “Reminiscences of W. H. Drummond,” Dalhousie Rev., 5 (1925–26): 161–69. M. J. Edwards, “William Henry Drummond,” The evolution of Canadian literature in English . . . , ed. M. J. Edwards et al. (4v., Toronto and Montreal, 1973), 2: 94–97. R. G. Moyles, English-Canadian literature to 1900: a guide to information sources (Detroit, 1976), 129–31. Gerald Noonan, “Drummond – the legend & the legacy,” Canadian Lit. (Vancouver), no.90 (autumn 1981): 179–87. Thomas O’Hagan, “A Canadian dialect poet,” Catholic World (New York), 77 (April–September 1903): 522–31; Intimacies in Canadian life and letters (Ottawa, 1927). R. E. Rashley, “W. H. Drummond and the dilemma of style,” Dalhousie Rev., 28 (1948 49): 387–96. L. B. Thompson, “The shelving of a people’s poet: the case of William Henry Drummond,” Journal of American Culture (Bowling Green, Ohio), 2 (1980): 682–89.

Cite This Article

Mary Jane Edwards, “DRUMMOND (Drumm), WILLIAM HENRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/drummond_william_henry_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/drummond_william_henry_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Mary Jane Edwards |

| Title of Article: | DRUMMOND (Drumm), WILLIAM HENRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |